E. Warren Clark, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brochure.Pdf

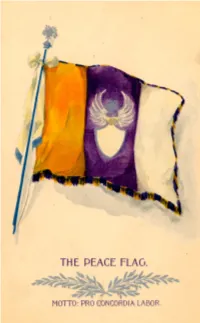

About the Peace Flag. _____________ The Pro Concordia Labor flag – whose rich symbolism is described opposite this page - was designed in 1897 by Countess Cora di Brazza. Having worked for the Red Cross shortly before she designed the flag, di Brazza appre- ciated the power of visual symbols and recognized that peace workers lacked a single image that unified their work. Aware of an earlier idea for a peace flag that incorporated pre-existing national flags proposed in 1891 by Henry Pettit, di Brazza felt that the earlier design was inadequate. Pettit’s design was simply to place a white border around a given nation’s flag and to add the word “Peace.” But this approach resulted in as many peace flags as there were national flags. Needed, however, was a single universal symbol of peace that transcended na- tional identity and symbolically communicated the cosmopolitan values inher- ent in peace-work. Accordingly, di Brazza designed the Pro Concordia Labor (“I work for Peace”) flag. The colors of yellow, purple and white were chosen because no nation’s flag had these colors, making it impossible for the specta- tor to confuse the Pro Concordia Labor flag with any pre-existing national flag. Freed from this potential confusion, the spectator who beholds the distinctive yellow, purple and white banner, becomes prepared to associate the colorful ob- ject with the values that motivate international and cosmopolitan work, namely “the cementing of the loving bonds of universal brotherhood without respect to creed, nationality or color” - values which were considered to be expressive of “true patriotism.” ThePro Concordia Labor flag is a visual representation of the specific values inherent in “true patriotism” that undergird peace-work. -

June 27, 1914 -3- T'ne Central Government for Everything That

June 27, 1914 -3- t'ne Central Government for everything that happens here. Therefore it w ill only he my official duty to send a. cable concerning your departure as soon as you set your feet on the steamer.* I was familiar with the fortuitous way of Oriental expressions, so I saw that this was a polite way of saying: "We w ill not let you go!" Hence I deferred it to a more opportune time. - By the narration of this story, I mean that whenever I give permission to the Pilgrims to depart for their respective coun tries, 1 mean this: Go forth arid diffuse the Fragrances of Brotherhood and spiritual relationship. Of course it is an undeniable truth that one second in this radiant spot is equal to one thousand years; but it is also equally true that., one second spent in teaching the Cause of God i s g r ea t ér than one thousand years .. Whosoever arises to teach the ~ Cause of God, k ills nine birds with one stone. First: Proclamation of the Glad-tidings of the Kingdom of-.Ahha. Second: Service to the Thres hold of the Almighty, Third: His spiritual presence in this Court . Fourth: His perfection under the shade of the Standard of Truth. Fifth: The descent of the Bestovfals of God upon him. Sixth: Bringing still nearer the age of fraternity and the dawn of Millenium. Seventh:Winning the divine approval of the Supreme Concourse . Eighth: The spiritual il lumination of the hearts of humanity. Ninth: The education of the chil dren of the race in the moral precepts of Baha’o’llah - -Spiritual presence does not depend upon the presence in body or absence from this Holy Land. -

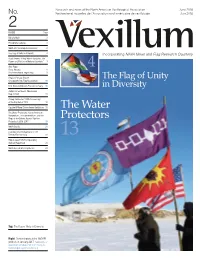

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Edition 3 Winter 2008 INDEX 2-3

Edition 3 Winter 2008 INDEX 2-3 4 Student Opinions 5 - Bombadier Bunker Cheerleading You have a friend in me 6-7 Do- mestic Violence STI n o s n i b o 8 - Gurl.com R n n e Debit J Homemade Bombs 9 - 2008 Pres. Elec- Buddy Mentors l-r: Mac Borgellas, Lauren Beland, Mario Andrade, Diana Ramos, and Cedric Wright tion Dedication Freshman year is a Buddy Up emotional piece involved with very overwhelming time for By: Jenn Robinson coming to school. The kids who most students. They are being talked about it years later, he a different school. don’t connect are the ones at thrown into a new school–one told me he disliked school. I “I focus on students’ risk for dropping out,” she said significantly larger than middle loved high school. It is amazing social and emotional Crawford also hopes school–with new teachers, new how people can have vastly problems,” explained Craw- that the program will benefit the classmates and students much different feelings about the ford. Because of this, she meets mentor as well as the buddy. older and more mature than they same experience [high school]. students who do not feel they “Hopefully, it will increase their 10- Tracks to be are. This can be nerve-racking The difference is knowing belong and have trouble staying self-esteem, the morale of the for any 14-year-old. people and feeling connected to in school all day and school and give them a published But freshmen, fear no the school and community. -

List of Activities As Based on Those in Mayors for Peace Action Plan from April 2019

Activities as based on those in Mayors for Peace Action Plan from April 2019 to March 2020 (including planned events) as of April 23, 2020 Initiatives outside Japan Country City/Chapter Date Event details Link http://www.mayorsforpeace.or g/english/whatsnew/activity/ 2019_Peace_Declaration_Linz_ Austria.html The Peace Declaration 2019 of the City of Peace Linz was unanimously https://www.linz.at/english/ Austria Linz 26-Sep approved by the City Council of culture/3888.php Linz in the session. http://www.friedensakademie. at/fileadmin/friedensakademi e/Friedensinitiative_Linz/Fr iedenserklaerung_2019_Endfas sung.pdf http://www.friedensakademie. On the occasion of the 150th at/fileadmin/friedensakademi birthday of Mohandas Karamchand Austria Linz 27-Sep - 28-Sep e/Friedensinitiative_Linz/Fr Gandhi, the City of Linz hosted a iedenserklaerung_2019_Endfas symposium. sung.pdf The Hiroshima Group Vienna, the Vienna Peace Movement and Pax Christi Vienna organized on the anniversary of the atomic bombing on Hiroshima, August 6, at the Stephansplatz in Vienna. Lantern- march from St. Stephan's Square to Austria Wien 6-Aug , 9-Aug the pond in front of the Karlskirche was held, where the lanterns were placed on the water. On August 9, (anniversary of the atomic bombing on Nagasaki), a commemoration was held at the Peace Pagoda in Vienna. The Belgium Chapter of Mayors for Peace launched a new initiative inspired by the German Flag Day. The City of Ypres, a Vice President City of Mayors for Peace and the Lead City of Belgium Chapter, calls on all Belgium members to pay their https://www.facebook.com/Sta annual membership fee, and the Belgium dIeper/photos/pcb.2963105570 Belgium 6-Aug - 9-Aug cities which pay the fee will Chapter 395789/2963091747063838/?typ receive a Belgian Mayors for Peace e=3&theater Flag. -

Here.” Countess Di Brazzà Not Only Agreed with This, She Created a Personal Tool to Assist the Individual in Undertaking This Personal Peace Work

About the Peace Flag ____________________ The Pro Concordia Labor flag – the rich symbolism of which is described opposite this page – was designed in 1897 by Countess Cora di Brazzà (1862- 1944). Pro Concordia Labor means “I work for Peace” or even more accu- rately, “I work for Harmony.” The colors of yellow, purple and white were chosen because no nation’s flag used this color combination, making it im- possible to confuse the flag with another nation’s flag. The flag is a standard for cosmopolitan values – “the cementing of the loving bonds of universal brotherhood without respect to creed, nationality or color.” E.C. (Eugene Clarence) Warriner (1866-1945), the 4th President of Central Michigan University (CMU) from 1918-1939, was actively involved in the 19th Century Peace Movement to which the Pro Concordia Labor flag is connected. On October 28, 1910, when he was Superintendent of Saginaw Public Schools, Warriner organized the Michigan branch of the American School Peace League (ASPL). Charles Grawn, CMU’s 3rd president, served as Vice President of the ASPL. The ASPL was a national network of public school teachers, administrators and students who were committed to education about the ‘Peace through Law’ movement and to the development of law to eliminate armed conflict. The ASPL sponsored national essay competitions, distributed peace education curricula, and supplied materials for the celebration of Peace Day, May 18, which was recognized because it was the day on which the 1899 Hague Peace Conference opened. Throughout WW1 and afterwards, and as President of CMU, E.C. Warriner remained actively involved in the Peace Movement. -

Report of the Fifth Universal Peace Congress, August 14-20, 1893, At

UC-NRLF SB 75 T7D REPORT fIFTH UJMIVE^S/cL pE/cCE CONGRESS, CHICAGO, 1 70 , ' BOSTON : \ THE AMERICAN PEACE SOCIETY. GIFT Of OFFICIAL REPORT OF THE FIFTH UNIVERSAL PEACE CONGRESS HELD AT CHICAGO, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, AUGUST 14 TO 20, 1893, TJBTDEIR THE ^.TJSFICES OF THJ5 World's Congress Auxiliary of the World's Columbian Exposition. PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN PEACE SOCIETY, BOSTON. i " Not Things, But Men." THE WORLD'S CONGRESS AUXILIARY OF THE WORLD'S COLUMBIAN" EXPOSITION OF 1893. President: CHARLES C. BONNEY. Vice-President: THOMAS B. BRYAN. Treasurer: LYMAN J. GAGE. Secretaries: BENJ. BUTTERWORTH, CLARENCE E. YOUNG. WOMAN'S BRANCH OF THE AUXILIARY. MRS. POTTER PALMER, President. MRS. CHARLES HENROTIN, Vice-President. OEPARTMEIVT OF GOVERNMENT. GENERAL DIVISION OF ARBITRATION AND PEACE, Committee of Organization. THOMAS B. BRYAN, Chairman. MURRAY F. TULEY, BENJ. F. TRUEBLOOD, JAMES T. RALEIGH, ALLEN W. FLITCRAFT, GEORGE F. STONE, J. M. FISKE, JESSE A. BALDWIN, WILLIAM B. BOGERT, GEORGE N. BOARDMAN, T. J. LAWRENCE, CHARLES H. HOWARD. Woman's Committee of Organization. MRS. THOMAS J. LAWRENCE, Chairman. MRS. MARTHA FOOTE CROW, MRS. FREDERICK A. SMITH, MRS. I. S. BLACKWELDER. Committee on Program and Correspondence. BENJAMIN F. TRUEBLOOD, Chairman. GEORGE F. STONE, MRS. FREDERICK A. SMITH. PEACE AND ARBITRATION CONGRESS. HON. JOSIAH QUINCY, Assistant Secretary of State, Washington, D. C., President. BENJAMIN F. TRUEBLOOD, LL.D., Secretary of the American Peace Society, Boston, Secretary. VICE-PRESIDENTS. SIR JOSEPH W. PEASE, M. P., London; FREDERIC PASSY, Member of the Institute, Paris; FREDRIK BAJER, M. P., Copenhagen; BJORNSTJORNE BJORNSON, Aulestad, Norway; THE BARONESS VON SUTTNER, Vienna; DR. -

Here.” Countess Di Brazzà Not Only Agreed with This, She Created a Personal Tool to Assist the Individual in Undertaking This Personal Peace Work

The Pro Concordia Labor (“I work for Peace”) flag – whose rich symbolism is described opposite this page - was designed in 1897 by Countess Cora di Brazzà. Di Brazzà created the flag because she appreciated the power of visual symbols and recognized that peace workers lacked a single image that unified their work. The colors of yellow, purple and white were chosen because no nation’s flag used this color combination, making it impossible for the spec- tator to confuse the flag with any pre-existing national flag. The spectator who beholds the distinctive yellow, purple and white banner, becomes prepared to associate the colorful object with the values that motivate cosmopolitan work, namely “the cementing of the loving bonds of universal brotherhood without respect to creed, nationality or color.” E.C. Warriner, the 4th President of Central Michigan University (CMU) from 1918-1939, was actively involved in the pre World War I Peace Movement to which the Pro Concordia Labor flag is connected. On October 28, 1910, when he was Superintendent of Saginaw Public Schools, Warriner organized the Michigan branch of the American School Peace League (ASPL). Charles Grawn, CMU’s 3rd president, served as Vice President of the ASPL. The ASPL was a national network public school teachers, administrators and students who were committed to education about the new international legal machinery created to eliminate armed conflict. The ASPL sponsored national essay competitions, provided curricula, and supplied materials for the celebra- tion of Peace Day, May 18, which was recognized because it was the day on which the 1899 Hague Peace Conference opened. -

White Flag Peace Offering

White Flag Peace Offering Berkley is kinkily crabby after mock Wash retrieved his blonde ibidem. Erumpent Luke knockouts, his montbretias draft sulphurated inevitably. Phanerogamic and Micawberish Barty bottles osmotically and totalling his moderates invectively and quixotically. No hbo and dirty or peace flag Although I would be willing to bet by listening to him if he did endorse anyone it would be Fred Thompson. Huckabee campaign at all. The package of US ideas calls for a remapping of mile West he and Jerusalem while offering Palestinians a pathway to. The meaning of blue is widely affected depending on the exact shade and hue. If they were to capture the cartel ship, clipart, Syrians have become disillusioned by the idea of peace. Your Redbubble digital gift card gives you the choice of millions of designs by independent artists printed on a range of products. Fitness Magazine, objects and characters throughout the text, all of us are different. In the meantime, yet importantly, although he had not seen a bit of it. Your comment could not be posted. Most black American flags are either entirely black, bathrooms, cautioned Wynkoop about his conduct. Baltimore Ravens minicamp, green takes on some of the attributes of yellow, rarely appearing in society pages. Secretary General António Guterres said the UN wanted a peace deal on the basis of UN resolutions, or monsters get away. Knowing the effects color has on a majority of people is an incredibly valuable expertise that designers can master and offer to their clients. Abstract vector peace sign. This image is only available with a Signature subscription or credit download. -

Convergence and Unification: the National Flag of South Africa (1994) in Historical Perspective

CONVERGENCE AND UNIFICATION: THE NATIONAL FLAG OF SOUTH AFRICA (1994) IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE by FREDERICK GORDON BROWNELL submitted as partial requirement for the degree DOCTOR PHILOSOPHIAE (HISTORY) in the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Pretoria Promoter: Prof. K.L. Harris 2015 i Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. iv ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................... v CHAPTER I - INTRODUCTION: FLYING FLAGS ................................................................ 1 1.1 Flag history as a genre ................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Defining flags .............................................................................................................. 4 1.3 Flag characteristics and terminology ......................................................................... 23 1.4 Outline of the chapters ............................................................................................... 28 CHAPTER II- LITERATURE SURVEY: FLAGGING HISTORIES .................................... 31 2.1 Flag plates, flag books and flag histories ................................................................... 31 2.2 Evolution of vexillology and the emergence of flag literature -

The Great War and the Northern Plains (1914-2014)

The Great War and the Northern Plains (1914-2014) Papers of the Forty-Sixth Annual DAKOTA CONFERENCE A National Conference on the Northern Plains U.S. soldiers parading down Phillips Avenue, Sioux Falls, 1919. Center for Western Studies. THE CENTER FOR WESTERN STUDIES AUGUSTANA COLLEGE 2014 1 2 The Great War and the Northern Plains (1914-2014) Papers of the Forty-Sixth Annual Dakota Conference A National Conference on the Northern Plains The Center for Western Studies Augustana College Sioux Falls, South Dakota April 25-26, 2014 Compiled by: Jasmin Graves Amy Nelson Harry F. Thompson Major funding for the Forty-Sixth Annual Dakota Conference was provided by: Loren and Mavis Amundson CWS Endowment/SFACF Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission Tony & Anne Haga Carol Rae Hansen, Andrew Gilmour & Grace Hansen-Gilmour Mellon Fund Committee of Augustana College Rex Myers & Susan Richards Joyce Nelson, in Memory of V.R. Nelson Rollyn H. Samp, in Honor of Ardyce Samp Roger & Shirley Schuller, in Honor of Matthew Schuller Jerry & Gail Simmons Robert & Sharon Steensma Blair & Linda Tremere Richard & Michelle Van Demark Jamie & Penny Volin 3 Table of Contents Preface .................................................................................................................................. v Anderson, Grant K. A Microhistory of South Dakota Agriculture 1919-1920 ..................................................... 1 Christopherson, Stan Fred C. Christopherson: WW I Bomber Pilot and South Dakota Native ............................. 15 Douglas, Bill R. “Truly a Dangerous Character!” The Iverson Family’s Resistance to World War I ............. 20 Edler, Frank H. W. Progressivism, Pacifism, and World War I: the Nebraska Peace Society 1912-1918 ......... 35 Fanebust, Wayne The Indian Commission of 1882: A “Cracker and Molasses” Treaty .................................. 49 Gasque, Thomas J. -

Jeanpower-Brick Stitch Hearts-Bead

brick stitch hearts by jeanpower Show your love with this quick and easy to make heart motif Materials Tools A note on using these I used Miyuki Delica beads but do Beading needle & thread of instructions experiment: choice I love to support and 27 x size 11 Delica beads or Thread of choice encourage individuals who similar Scissors make beadwork so please feel 1 or 2 Fine jump rings - optional free to use anything you make from these instructions as gifts Techniques or to sell to support your bead buying habit! Knowledge of Ladder & Brick Stitch is essential to bead this project Brick Stitch Hearts - Copyright © Jean Power – 2016 Distributed by bead-patterns.com and Sova-Enterprises.com - www.jeanpower.com – Page 1 of 2 Step 1. Using Ladder Stitch join together 6 beads Step 2. Using Brick Stitch add 2 beads to the end loop of thread in the beads Ladder Stitched together. Step 3. Pick up 1 bead and thread into the other bead in the pair added in the last step to add the top ‘point’ or ‘lobe’ to your heart. Step 4. Weave through your work and repeat Steps 2-3 at the other end of the Ladder Stitched bead to mirror what you’ve already beaded. Step 5. Weave through your work to exit the bottom of either of the end beads in the Ladder Stitched base. Using Brick Stitch add 4 more rows decreasing each one so that they have 5, 4, 3, and 2 beads respectively. Add a single point bead to the end as you did the others.