Uncle Ned's Mountain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brochure.Pdf

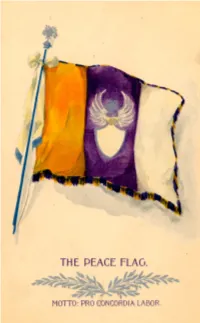

About the Peace Flag. _____________ The Pro Concordia Labor flag – whose rich symbolism is described opposite this page - was designed in 1897 by Countess Cora di Brazza. Having worked for the Red Cross shortly before she designed the flag, di Brazza appre- ciated the power of visual symbols and recognized that peace workers lacked a single image that unified their work. Aware of an earlier idea for a peace flag that incorporated pre-existing national flags proposed in 1891 by Henry Pettit, di Brazza felt that the earlier design was inadequate. Pettit’s design was simply to place a white border around a given nation’s flag and to add the word “Peace.” But this approach resulted in as many peace flags as there were national flags. Needed, however, was a single universal symbol of peace that transcended na- tional identity and symbolically communicated the cosmopolitan values inher- ent in peace-work. Accordingly, di Brazza designed the Pro Concordia Labor (“I work for Peace”) flag. The colors of yellow, purple and white were chosen because no nation’s flag had these colors, making it impossible for the specta- tor to confuse the Pro Concordia Labor flag with any pre-existing national flag. Freed from this potential confusion, the spectator who beholds the distinctive yellow, purple and white banner, becomes prepared to associate the colorful ob- ject with the values that motivate international and cosmopolitan work, namely “the cementing of the loving bonds of universal brotherhood without respect to creed, nationality or color” - values which were considered to be expressive of “true patriotism.” ThePro Concordia Labor flag is a visual representation of the specific values inherent in “true patriotism” that undergird peace-work. -

June 27, 1914 -3- T'ne Central Government for Everything That

June 27, 1914 -3- t'ne Central Government for everything that happens here. Therefore it w ill only he my official duty to send a. cable concerning your departure as soon as you set your feet on the steamer.* I was familiar with the fortuitous way of Oriental expressions, so I saw that this was a polite way of saying: "We w ill not let you go!" Hence I deferred it to a more opportune time. - By the narration of this story, I mean that whenever I give permission to the Pilgrims to depart for their respective coun tries, 1 mean this: Go forth arid diffuse the Fragrances of Brotherhood and spiritual relationship. Of course it is an undeniable truth that one second in this radiant spot is equal to one thousand years; but it is also equally true that., one second spent in teaching the Cause of God i s g r ea t ér than one thousand years .. Whosoever arises to teach the ~ Cause of God, k ills nine birds with one stone. First: Proclamation of the Glad-tidings of the Kingdom of-.Ahha. Second: Service to the Thres hold of the Almighty, Third: His spiritual presence in this Court . Fourth: His perfection under the shade of the Standard of Truth. Fifth: The descent of the Bestovfals of God upon him. Sixth: Bringing still nearer the age of fraternity and the dawn of Millenium. Seventh:Winning the divine approval of the Supreme Concourse . Eighth: The spiritual il lumination of the hearts of humanity. Ninth: The education of the chil dren of the race in the moral precepts of Baha’o’llah - -Spiritual presence does not depend upon the presence in body or absence from this Holy Land. -

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

The Battle of Ridgefield: April 27, 1777

American Revolution & Colonial Life Programs Pre and Post Lesson Plans & Activities The Battle of Ridgefield: April 27, 1777 • The Battle of Ridgefield was the only inland battle fought in Connecticut during the Revolutionary War. • Captain Benedict Arnold was the main commander for the battle as the British marched upon a weak Colonial Army. Arnold's defenses kept the British at bay until the larger army could come later. • Brigadier General Gold Selleck Silliman of Fairfield was also involved in the battle. In the primary source letter below, he sends word to General Wooster that they need reinforcements. • Silliman’s 2nd wife, Mary Silliman, writes to her parents after the battle, relieved that her husband and son were unharmed. Although her parents are only a few towns away, she is unable to travel the distance. • Another primary source is a silhouette of Lieutenant Colonel Abraham Gould of Fairfield, who died during the battle. At the Fairfield Museum: • Students will view a painted portrait of Mary Silliman in the galleries. • Students will see the grave marker for General Gold Selleck Silliman, his first wife, and a few of his children. • Students will also see the grave marker of Lieutenant Colonel Abraham Gould. Fairfield Museum & History Center | Fairfieldhistory.org | American Revolution: The Battle of Ridgefield A brief synopsis – The Battle of Fairfield: General Tryon of the British army thought that he would be warmly received by the people of Ridgefield after taking out a Colonial supply post just days earlier. Tryon, to his dismay, learned that the town was being barricaded by none other than General Benedict Arnold. -

Student Activities Packet

Name: ____________________________ Date: _____________________________ Activity 1: Be a History Detective! Directions: There are many ways historians or museum professionals can learn about the past. Many times we think primary sources are only writings, letters, papers or books. Another way we can learn about the past is from artifacts or images. In this activity we are going to ask you to act like a detective – you will have 2 minutes to look at one image and then answer the following three questions. Imagine that this image was left behind with no description so think creatively and build a possible story about what it might be showing us. Answer these questions after spending 2 minutes look at the image. There are no wrong answers – but every answer must be supported by what you SEE in the image. 1. What is going on in this picture? 2. What do you SEE that makes you say that? 3. What else do you see? (Take a second look and add to your detective work!) 1 ©Keeler Tavern Museum & History Center 2020 Name: ____________________________ Date: _____________________________ Activity 2: An Introduction to the Battle of Ridgefield Directions: Read the following questions before listening to the presentation on the Battle of Ridgefield – it will help you know what to listen for! You can answer the questions as you listen or come back to answer them when the presentation is done. 1. When was Ridgefield established? Who was living in the area before the English colonists? 2. Why was Lott 2, the house of Benjamin Hoytt and later Timothy Keeler, a good place to establish a tavern? 3. -

Edition 3 Winter 2008 INDEX 2-3

Edition 3 Winter 2008 INDEX 2-3 4 Student Opinions 5 - Bombadier Bunker Cheerleading You have a friend in me 6-7 Do- mestic Violence STI n o s n i b o 8 - Gurl.com R n n e Debit J Homemade Bombs 9 - 2008 Pres. Elec- Buddy Mentors l-r: Mac Borgellas, Lauren Beland, Mario Andrade, Diana Ramos, and Cedric Wright tion Dedication Freshman year is a Buddy Up emotional piece involved with very overwhelming time for By: Jenn Robinson coming to school. The kids who most students. They are being talked about it years later, he a different school. don’t connect are the ones at thrown into a new school–one told me he disliked school. I “I focus on students’ risk for dropping out,” she said significantly larger than middle loved high school. It is amazing social and emotional Crawford also hopes school–with new teachers, new how people can have vastly problems,” explained Craw- that the program will benefit the classmates and students much different feelings about the ford. Because of this, she meets mentor as well as the buddy. older and more mature than they same experience [high school]. students who do not feel they “Hopefully, it will increase their 10- Tracks to be are. This can be nerve-racking The difference is knowing belong and have trouble staying self-esteem, the morale of the for any 14-year-old. people and feeling connected to in school all day and school and give them a published But freshmen, fear no the school and community. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

Of the Gospel

HAWAII HAWAII HAWAII WORLD The diocese’s new plan, Bishop names seven Iconic festival of liturgical At Central African Republic shifts from a more inward Jubilee Holy Year of Mercy music and art celebrates 40 mosque, Pope Francis prays to a more outward focus indulgence churches years, changes its name for ‘salam,’ peace Page 3 Page 3 Page 4 Page 10 HawaiiVOLUME 78, NUMBER 25 CatholicFRIDAY, DECEMBER 4, 2015 Herald$1 BISHOP’S LETTER DIOCESE OF HONOLULU DIOCESAN PASTORAL PLAN FOR 2016-2020 STEWARDS OF THE GOSPEL Dear Clergy, Religious and Faithful of the Diocese of Honolulu, Peace be with you! Over the past several months I have met with parish leaders in each of our nine vicariates to receive input on the renewal of our diocesan pasto- ral plan. I am grateful to all who shared their insights so that we can be good stewards of the resources of time, talent, and treasure that the Lord has entrusted to us for his mission. I am particularly grateful to James Walsh, Director of Pastoral Planning, for his great work on the develop- ment of this pastoral plan. Those who are familiar with our last pastoral plan “The Roadmap for Our Mission” will notice similarities between this current plan and the “Roadmap.” While the priorities may be similar, I want this pastoral plan to help us all direct our attention outward, and not simply to focus on the internal structures and programs of our diocese and parishes. This is in keeping with the mandate of Jesus himself: “Go, therefore, and make dis- ciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have com- manded you. -

List of Activities As Based on Those in Mayors for Peace Action Plan from April 2019

Activities as based on those in Mayors for Peace Action Plan from April 2019 to March 2020 (including planned events) as of April 23, 2020 Initiatives outside Japan Country City/Chapter Date Event details Link http://www.mayorsforpeace.or g/english/whatsnew/activity/ 2019_Peace_Declaration_Linz_ Austria.html The Peace Declaration 2019 of the City of Peace Linz was unanimously https://www.linz.at/english/ Austria Linz 26-Sep approved by the City Council of culture/3888.php Linz in the session. http://www.friedensakademie. at/fileadmin/friedensakademi e/Friedensinitiative_Linz/Fr iedenserklaerung_2019_Endfas sung.pdf http://www.friedensakademie. On the occasion of the 150th at/fileadmin/friedensakademi birthday of Mohandas Karamchand Austria Linz 27-Sep - 28-Sep e/Friedensinitiative_Linz/Fr Gandhi, the City of Linz hosted a iedenserklaerung_2019_Endfas symposium. sung.pdf The Hiroshima Group Vienna, the Vienna Peace Movement and Pax Christi Vienna organized on the anniversary of the atomic bombing on Hiroshima, August 6, at the Stephansplatz in Vienna. Lantern- march from St. Stephan's Square to Austria Wien 6-Aug , 9-Aug the pond in front of the Karlskirche was held, where the lanterns were placed on the water. On August 9, (anniversary of the atomic bombing on Nagasaki), a commemoration was held at the Peace Pagoda in Vienna. The Belgium Chapter of Mayors for Peace launched a new initiative inspired by the German Flag Day. The City of Ypres, a Vice President City of Mayors for Peace and the Lead City of Belgium Chapter, calls on all Belgium members to pay their https://www.facebook.com/Sta annual membership fee, and the Belgium dIeper/photos/pcb.2963105570 Belgium 6-Aug - 9-Aug cities which pay the fee will Chapter 395789/2963091747063838/?typ receive a Belgian Mayors for Peace e=3&theater Flag. -

He Ahu Mo'olelo

He Ahu Mo‘olelo: E Ho‘okahua i ka Paepae Mo‘olelo Palapala Hawai‘i A Cairn of Stories: Establishing a Foundation of Hawaiian Literature ku‘ualoha ho‘omanawanui ‘Ōlelo Hō‘ulu‘ulu / Summary “What is mo‘olelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian literature)?”1 This essay seeks to answer this and related questions. It articulates a foundation of mo‘olelo Hawai‘i in the twenty-first century as constructed from a long, rich history of oral tradition, performance, and writ- ing, in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language), ‘ōlelo Pelekānia (English), and ‘ōlelo pa‘i‘ai (Hawai‘i Creole English, HCE, or “pidgin”). This essay maps the mo‘okū‘auhau (gene- alogy) of mo‘olelo Hawai‘i in its current form as a contemporized (post-eighteenth cen- tury) cultural practice resulting from the longer-standing tradition of haku (composing, including strictly oral compositions) and kākau (imprinting, writing). Beginning in the 1830s, kākau and pa‘i (printing) were composed from ‘ike Hawai‘i (Hawaiian knowl- edge) passed down mai ka pō mai (from the ancient past), reflecting innovations in the recording and transmission of ‘ike Hawai‘i, including mo‘olelo (narratives, stories, histories). ‘Ōlelo Mua / Introduction When I entered the PhD program in English at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in 1997, a professor stopped me in the hall one day. “What is there to possibly study in Hawaiian literature? Is that even a ‘thing’?” she inquired. While incensed by such ignorance, I politely smiled and replied, “Why, the same thing you do with English literature—periods, genres, and authors.” She seemed satisfied with my response, but also befuddled. -

Kauai Marriage Records 1845

Kauai Marriage Records 1845 - 1929 from Hawaii State Archives Name Date Book and Page Location _____(k) - Pale : 04-24-1838 , Kalina (k) - Kalaiki : 04-27-1838 , Lauli (k) - Ono : 05-01-1838 , Kalaipaka (k) - Kulepe : 05-07-1838 , Opunui (k) - Kealiikehekili : 05-07-1838 , Kaunuohua (k) - Moo : 07-04-1838 , Halau (k) - Kahauna : 07-11-1838 , Naehu (k) - Kapapa : 07-11-1838 K-8a p137 Unknown __pe (k) - Keaka : 12-30-1833 , Pahiha (k) - Nahalenui : 12-30-1833 , Kapuaiki (k) - Kepuu : 12-30-1833 , Molina (k) - Nailimala : 12-30-1833 , Maipehu (k) - Awili : 01-14-1834 , Kupehea (k) - Napalapalai : 01-14-1834 , Naluahi (k) - Naoni : 01-14-1834 K-8a p101 Unknown Aana (k) - Kahiuaia , Aaana (k) - Kahiuaia :1879-10-30 : K-15 p14 Waimea Aarona, Palupalu (k) - Kamaka, Sela :1897-06-26 : K-19 p29 Hanalei Abaca, Militan (k) - Lovell, Mary :1928-06-23 : K-26 p422 Kawaihau Abargis, Rufo (k) - Apu, Harriet :1918-05-18 : K-30 p12 Lihue Abe, Asagiro (k) - Amano, Toyono :1912-04-19 : K-28 p33 Lihue Abilliar, Branlio (k) - Riveira, Isabella Torres :1926-03-24 : K-26 p325 Kawaihau Aboabo, Antonio (k) - Gaspi, Anastacia :1925-03-02 : K-27 p215 Koloa Abreu, David (k) - Cambra, Frances :1927-11-16 : K-27 p346 Koloa Abreu, Joe G. (k) - Farias, Lucy :1922-08-25 : K-27 p68 Koloa Abreu, Jose (k) - Ludvina Gregoria :1905-01-16 : K-24 p41 Koloa Abulon, Juan (k) - Kadis, Juliana :1923-06-25 : K-22 p18 Waimea Acob, Cornillo (k) - Cadavona, Leancia :1928-12-16 : K-29 p121 Lihue Acoba, Claudio (k) - Agustin, Agapita :1924-05-17 : K-27 p151 Koloa Acosta, Balbino (k) - -

253537449.Pdf

CD 105402 HAWAII ISLES OF ENCHANTMENT By CLIFFORD GESSLER Illustrated by E. H. SUYDAM D. APPLETON- CENTURY COMPANY INCORPORATED NEW YORK LONDON 1938 COPYRIGHT, 1937, BY JD. APPLETON-CENTURY COMPANY, INC. rights reserved. This book, or part** thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher. Illustrations copyright, 937, by JE. HL Suydam Printed in the United States of America INTRODUCTION write of it or must RO away from Hawaii to is bewildered by KO away and return. A newcomer dazed the sharp impact of ONEits contradictions, by resident of long standing, on the thronging impressions. A so for that he other hand, tends to take the islands granted them to the stranger. may he handicapped in interpreting to be in a sense both One is fortunate, therefore, perhaps with the zeal kamaaina and malihini, neither exaggerating V Introduction *$: new convert the charm of those bright islands nor al~ dulled lotting it to be obscured with sensitivity by prolonged and not too daily familiarity. Time, not too long, distance, great, help to attain balance. The aim of this book is to write a national biography a character illumi- and to paint, in broad strokes, portrait, nated here and there by anecdote, of a country and a people that I have loved. Nor shall I tell here all I know about any one aspect of the islands. Not now, at any rate; this is not that kind of book. Scandal seldom reveals the true spirit of a community. The exception is not a reliable index, and controversies are like the shattered window which caused the policeman, after inspecting it without and within, to exclaim: "It's worse than I thought; it's broke on both sides!" Here again the long view is the clearest.