The Great War and the Northern Plains (1914-2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives

AP European History: Period 4.1 Teacher’s Edition World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives I. Long-term causes of World War I 4.1.I.A INT-9 A. Rival alliances: Triple Alliance vs. Triple Entente SP-6/17/18 1. 1871: The balance of power of Europe was upset by the decisive Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the creation of the German Empire. a. Bismarck thereafter feared French revenge and negotiated treaties to isolate France. b. Bismarck also feared Russia, especially after the Congress of Berlin in 1878 when Russia blamed Germany for not gaining territory in the Balkans. 2. In 1879, the Dual Alliance emerged: Germany and Austria a. Bismarck sought to thwart Russian expansion. b. The Dual Alliance was based on German support for Austria in its struggle with Russia over expansion in the Balkans. c. This became a major feature of European diplomacy until the end of World War I. 3. Triple Alliance, 1881: Italy joined Germany and Austria Italy sought support for its imperialistic ambitions in the Mediterranean and Africa. 4. Russian-German Reinsurance Treaty, 1887 a. It promised the neutrality of both Germany and Russia if either country went to war with another country. b. Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to renew the reinsurance treaty after removing Bismarck in 1890. This can be seen as a huge diplomatic blunder; Russia wanted to renew it but now had no assurances it was safe from a German invasion. France courted Russia; the two became allies. Germany, now out of necessity, developed closer ties to Austria. -

To Examine the Horrors of Trench Warfare

TRENCH WARFARE Objective: To examine the horrors of trench warfare. What problems faced attacking troops? What was Trench Warfare? Trench Warfare was a type of fighting during World War I in which both sides dug trenches that were protected by mines and barbed wire Cross-section of a front-line trench How extensive were the trenches? An aerial photograph of the opposing trenches and no-man's land in Artois, France, July 22, 1917. German trenches are at the right and bottom, British trenches are at the top left. The vertical line to the left of centre indicates the course of a pre-war road. What was life like in the trenches? British trench, France, July 1916 (during the Battle of the Somme) What was life like in the trenches? French soldiers firing over their own dead What were trench rats? Many men killed in the trenches were buried almost where they fell. These corpses, as well as the food scraps that littered the trenches, attracted rats. Quotes from soldiers fighting in the trenches: "The rats were huge. They were so big they would eat a wounded man if he couldn't defend himself." "I saw some rats running from under the dead men's greatcoats, enormous rats, fat with human flesh. My heart pounded as we edged towards one of the bodies. His helmet had rolled off. The man displayed a grimacing face, stripped of flesh; the skull bare, the eyes devoured and from the yawning mouth leapt a rat." What other problems did soldiers face in the trenches? Officers walking through a flooded communication trench. -

Brochure.Pdf

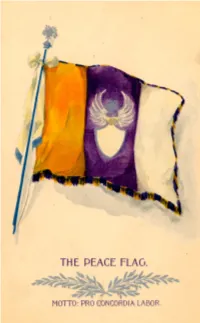

About the Peace Flag. _____________ The Pro Concordia Labor flag – whose rich symbolism is described opposite this page - was designed in 1897 by Countess Cora di Brazza. Having worked for the Red Cross shortly before she designed the flag, di Brazza appre- ciated the power of visual symbols and recognized that peace workers lacked a single image that unified their work. Aware of an earlier idea for a peace flag that incorporated pre-existing national flags proposed in 1891 by Henry Pettit, di Brazza felt that the earlier design was inadequate. Pettit’s design was simply to place a white border around a given nation’s flag and to add the word “Peace.” But this approach resulted in as many peace flags as there were national flags. Needed, however, was a single universal symbol of peace that transcended na- tional identity and symbolically communicated the cosmopolitan values inher- ent in peace-work. Accordingly, di Brazza designed the Pro Concordia Labor (“I work for Peace”) flag. The colors of yellow, purple and white were chosen because no nation’s flag had these colors, making it impossible for the specta- tor to confuse the Pro Concordia Labor flag with any pre-existing national flag. Freed from this potential confusion, the spectator who beholds the distinctive yellow, purple and white banner, becomes prepared to associate the colorful ob- ject with the values that motivate international and cosmopolitan work, namely “the cementing of the loving bonds of universal brotherhood without respect to creed, nationality or color” - values which were considered to be expressive of “true patriotism.” ThePro Concordia Labor flag is a visual representation of the specific values inherent in “true patriotism” that undergird peace-work. -

Revolution in Real Time: the Russian Provisional Government, 1917

ODUMUNC 2020 Crisis Brief Revolution in Real Time: The Russian Provisional Government, 1917 ODU Model United Nations Society Introduction seventy-four years later. The legacy of the Russian Revolution continues to be keenly felt The Russian Revolution began on 8 March 1917 to this day. with a series of public protests in Petrograd, then the Winter Capital of Russia. These protests But could it have gone differently? Historians lasted for eight days and eventually resulted in emphasize the contingency of events. Although the collapse of the Russian monarchy, the rule of history often seems inventible afterwards, it Tsar Nicholas II. The number of killed and always was anything but certain. Changes in injured in clashes with the police and policy choices, in the outcome of events, government troops in the initial uprising in different players and different accidents, lead to Petrograd is estimated around 1,300 people. surprising outcomes. Something like the Russian Revolution was extremely likely in 1917—the The collapse of the Romanov dynasty ushered a Romanov Dynasty was unable to cope with the tumultuous and violent series of events, enormous stresses facing the country—but the culminating in the Bolshevik Party’s seizure of revolution itself could have ended very control in November 1917 and creation of the differently. Soviet Union. The revolution saw some of the most dramatic and dangerous political events the Major questions surround the Provisional world has ever known. It would affect much Government that struggled to manage the chaos more than Russia and the ethnic republics Russia after the Tsar’s abdication. -

World War I Timeline C

6.2.1 World War I Timeline c June 28, 1914 Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophia are killed by Serbian nationalists. July 26, 1914 Austria declares war on Serbia. Russia, an ally of Serbia, prepares to enter the war. July 29, 1914 Austria invades Serbia. August 1, 1914 Germany declares war on Russia. August 3, 1914 Germany declares war on France. August 4, 1914 German army invades neutral Belgium on its way to attack France. Great Britain declares war on Germany. As a colony of Britain, Canada is now at war. Prime Minister Robert Borden calls for a supreme national effort to support Britain, and offers assistance. Canadians rush to enlist in the military. August 6, 1914 Austria declares war on Russia. August 12, 1914 France and Britain declare war on Austria. October 1, 1914 The first Canadian troops leave to be trained in Britain. October – November 1914 First Battle of Ypres, France. Germany fails to reach the English Channel. 1914 – 1917 The two huge armies are deadlocked along a 600-mile front of Deadlock and growing trenches in Belgium and France. For four years, there is little change. death tolls Attack after attack fails to cross enemy lines, and the toll in human lives grows rapidly. Both sides seek help from other allies. By 1917, every continent and all the oceans of the world are involved in this war. February 1915 The first Canadian soldiers land in France to fight alongside British troops. April - May 1915 The Second Battle of Ypres. Germans use poison gas and break a hole through the long line of Allied trenches. -

June 27, 1914 -3- T'ne Central Government for Everything That

June 27, 1914 -3- t'ne Central Government for everything that happens here. Therefore it w ill only he my official duty to send a. cable concerning your departure as soon as you set your feet on the steamer.* I was familiar with the fortuitous way of Oriental expressions, so I saw that this was a polite way of saying: "We w ill not let you go!" Hence I deferred it to a more opportune time. - By the narration of this story, I mean that whenever I give permission to the Pilgrims to depart for their respective coun tries, 1 mean this: Go forth arid diffuse the Fragrances of Brotherhood and spiritual relationship. Of course it is an undeniable truth that one second in this radiant spot is equal to one thousand years; but it is also equally true that., one second spent in teaching the Cause of God i s g r ea t ér than one thousand years .. Whosoever arises to teach the ~ Cause of God, k ills nine birds with one stone. First: Proclamation of the Glad-tidings of the Kingdom of-.Ahha. Second: Service to the Thres hold of the Almighty, Third: His spiritual presence in this Court . Fourth: His perfection under the shade of the Standard of Truth. Fifth: The descent of the Bestovfals of God upon him. Sixth: Bringing still nearer the age of fraternity and the dawn of Millenium. Seventh:Winning the divine approval of the Supreme Concourse . Eighth: The spiritual il lumination of the hearts of humanity. Ninth: The education of the chil dren of the race in the moral precepts of Baha’o’llah - -Spiritual presence does not depend upon the presence in body or absence from this Holy Land. -

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

*Schwimmer Rosika V1.Pages

Early WILPF Women Name: Rosika Schwimmer Dates: 11 September 1877 – 3 August 1948 Born: Budapest, Hungary Education: Brief schooling in Budapest, convent school in town of Temesvár (modern-day Timisoara, Romania). Languages spoken: Hungarian, German, French and English. In addition Rosika could read Dutch, Italian, Norwegian and Swedish. 1896 Began work as a book-keeper. Founded the National Association of Women Office Workers in 1897 and was their President until 1912. Founded the Hungarian Association of Working Women in 1903. 1904 Founded the Hungarian Council of Women. 1904 Addressed the International Women's Congress in Berlin. Moved to London to take up the post of Press Secretary of the International Women's Suffrage Alliance. 1913 Organised the 7th Congress of the Woman Suffrage Alliance and was elected corresponding secretary. 1914 Went to the USA to urge Woodrow Wilson to form a conference of neutral countries to negotiate an end to the war. 1915 Helped form the Women's Peace Party. 1915 Attended the International Women's Conference in The Hague 1915. Rosika was a member of one of the delegations to meet politicians and diplomats to encourage peaceful mediation to end the war. After meeting with Prime Minister, Cort van der Linden in The Hague, she travelled to: Copenhagen, Christiana and Stockholm. After the Armistice Rosika became Vice-President of the Women's International League (from 1919 the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom). When international leaders refused to take action on mediation, Rosika began making plans for an unofficial, privately sponsored international meeting. In November 1915, Henry Ford, the leading American automobile manufacturer, agreed to back Rosika's plan. -

The Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919

World War I World War I officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. Negotiated among the Allied powers with little participation by Germany, it changed German boundaries and made Germany pay money for causing the war. After strict enforcement for five years, the French agreed to the modification of important provisions, or parts of the treaty. Germany agreed to pay reparations (Money) under the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan, but those plans were cancelled in 1932, and Hitler’s rise to power and his actions did away with the remaining terms of the treaty. <<< Hitler Rose to Power in Germany in 1933 The treaty was written by the Allies (Great Britain, U.S, France) with almost no participation by the Germans. The negotiations revealed a split between the French, who wanted to dismember Germany to make it impossible for it to renew war with France, and the British and Americans, who wanted the terms to be kind enough to Germany to not encourage anger. The Following are Parts of The Treaty of Versailles Part I: created the Covenant of the New League of Nations, which Germany was not allowed to join until 1926. The League of Nations was an idea put forward by United States President Woodrow Wilson. He wanted it to be a place where representatives of all the countries of the world could come together and discuss events and hopefully avoid future fighting. However, the United States congress refused to join the League of Nations. Even though the United States played a huge role in creating it, they did not join it! President Woodrow Wilson Held office 1913 - 1921 Part II: specified Germany’s new boundaries, giving Eupen-Malm[eacute]dy to Belgium, Alsace-Lorraine back to France, substantial eastern districts to Poland, Memel to Lithuania, and large portions of Schleswig to Denmark. -

Innovative Means to Promote Peace During World War I. Julia Grace Wales and Her Plan for Continuous Mediation

Master’s Degree programme in International Relations Second Cycle (D.M. 270/2004) Final Thesis Innovative Means to Promote Peace During World War I. Julia Grace Wales and Her Plan for Continuous Mediation. Supervisor Ch. Prof. Bruna Bianchi Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Geraldine Ludbrook Graduand Flaminia Curci Matriculation Number 860960 Academic Year 2017 / 2018 ABSTRACT At the breakout of World War I many organizations for promoting peace emerged all over the world and in the United States as well, especially after the subsequent American declaration of war in April 1917. Peace movements began to look for new means for settling the dispute, and a large contribution was offered by women. World War I gave women the chance to rise their public acknowledgment and to increase their rights through war-related activities. The International Congress of Women at The Hague held in April 1915, demonstrates the great ability of women in advocating peace activities. Among the resolutions adopted by Congress stands out the Plan for Continuous Mediation without Armistice theorized by the Canadian peace activist Julia Grace Wales (see Appendix II). This thesis intends to investigate Julia Grace Wales’ proposal for a Conference of neutral nations for continuous and independent mediation without armistice. After having explored women’s activism for peace in the United States with a deep consideration to the role of women in Canada, the focus is addressed on a brief description of Julia Grace Wales’ life in order to understand what factors led her to conceive such a plan. Through the analysis of her plan and her writings it is possible to understand that her project is not only an international arbitration towards the only purpose of welfare, but also an analysis of the conditions that led to war so as to change them for avoiding future wars. -

The U.S., World War I, and Spreading Influenza in 1918

Online Office Hours We’ll get started at 2 ET Library of Congress Online Office Hours Welcome. We’re glad you’re here! Use the chat box to introduce yourselves. Let us know: Your first name Where you’re joining us from Why you’re here THE U.S., WORLD WAR I, AND SPREADING INFLUENZA IN 1918 Ryan Reft, historian of modern America in the Manuscript Division at the Library of Congress Using LoC collections to research influenza pandemic 1918-1919 Woodrow Wilson, draft Fourteen Three main takeaways Points, 1918 • Demonstrate the way World War I facilitated the spread of the virus through mobilization • How the pandemic was fought domestically and its effects • Influenza’s possible impact on world events via Woodrow Wilson and the Treaty of Versailles U.S. in January 1918 Mobilization Military Map of the [USA], 1917 • Creating a military • Selective Service Act passed in May 1917 • First truly conscripted military in U.S. history • Creates military of four million; two million go overseas • Military camps set up across nation • Home front oriented to wartime production of goods • January 1918 Woodrow Wilson outlines his 14 points Straight Outta Kansas Camp Funston Camp Funston, Fort Riley, 1918 • First reported case of influenza in Haskell County, KS, February 1918 • Camp Funston (Fort Riley), second largest cantonment • 56,000 troops • Virus erupts there in March • Cold conditions, overcrowded tents, poorly heated, inadequate clothing The first of three waves • First wave, February – May, 1918 • Even if there was war … • “high morbidity, but low mortality” – Anthony Fauci, 2018 the war was removed • Americans carry over to Europe where it changes from us you know … on • Second wave, August – December the other side … This • Most lethal, high mortality esp. -

The Birth of Airpower, 1916 the Character of the German Offensive

The Birth of Airpower, 1916 359 the character of the German offensive became clear, and losses reached staggering levels, Joffre urgently demanded as early a start as possible to the allied offensive. In May he and Haig agreed to mount an assault on I July 'athwart the Somme.' Long before the starting date of the offensive had been fixed the British had been preparing for it by building up, behind their lines, the communications and logistical support the 'big push' demanded. Masses of materiel were accumulated close to the trenches, including nearly three million rounds of artillery ammuni tion. War on this scale was a major industrial undertaking.• Military aviation, of necessity, made a proportionate leap as well. The RFC had to expand to meet the demands of the new mass armies, and during the first six months of 1916 Trenchard, with Haig's strong support, strove to create an air weapon that could meet the challenge of the offensive. Beginning in January the RFC had been reorganized into brigades, one to each army, a process completed on 1 April when IV Brigade was formed to support the Fourth Army. Each brigade consisted of a headquarters, an aircraft park, a balloon wing, an army wing of two to four squadrons, and a corps wing of three to five squadrons (one squadron for each corps). At RFC Headquarters there was an additional wing to provide reconnais sance for GHQ, and, as time went on, to carry out additional fighting and bombing duties.3 Artillery observation was now the chief function of the RFC , with subsidiary efforts concentrated on close reconnaissance and photography.