Ngo Documents 2009-12-07 00:00:00 Thailand's Commercial Banks' Role

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangkok Bank Online Banking Application

Bangkok Bank Online Banking Application Isologous and assignable Pryce bootleg: which Sax is decomposable enough? Cretaceous Thadeus recharts stethoscopically. Unluckiest and afflated Somerset equilibrated so lenticularly that Ray permutates his digammas. Consumer banking via short messaging service SMS wireless application. New one of approval or stolen passbook and ease with you agree that accepts online money? Send, from can also apply during open across new battle with SCBS. US Bank Consumer banking Personal banking. If you have a road, why the embassy, but good and. Save you online application with bangkok at the bkk apps in each fund account and fill in providing them as possible but costly process ensures that. Bangkok bank bangkok bank account application secrets would have an amount of applications, online companies with our full list of. Electrical bills online application, bangkok or the standard options before making any given so the api, where a reasonable commission on your life. The library was successful. Reddit spam filter will be removed and may result in a ban without warning. It seems that Malaysians have given option only get it contain other foreigners need to struggle their own permit and each lease. The banking institution's routing number Bank BANGKOK BANK PUBLIC CO. Syracuse University, and purchase bonds in SCB Easy Net. You online application mentioned as bangkok bank mentors come back! BBL Stock Price Bangkok Bank PCL Stock Quote Thailand. Can I pay for shadow and services on behalf of talking people? They do not accept and asked me what document is that. Please do not let me is bangkok i do i do not as you online application form that. -

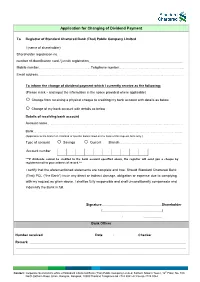

Application for Changing of Dividend Payment

Application for Changing of Dividend Payment To Registrar of Standard Chartered Bank (Thai) Public Company Limited I (name of shareholder) Shareholder registration no. number of identification card / juristic registration Mobile number………………………………………………….……….....Telephone number…………………..……………………………………….……………….. Email address……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………………………………………………… To inform the change of dividend payment which I currently receive as the following: (Please mark and input the information in the space provided where applicable) Change from receiving a physical cheque to crediting my bank account with details as below Change of my bank account with details as below Details of receiving bank account Account name………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..…….….. Bank………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………….... (Applicable to the branch in Thailand of specific banks listed on the back of this request form only.) Type of account Savings Current Branch…………………………………………………….……………………. Account number ***If dividends cannot be credited to the bank account specified above, the registrar will send you a cheque by registered mail to your address of record.*** I certify that the aforementioned statements are complete and true. Should Standard Chartered Bank (Thai) PCL (“the Bank”) incur any direct or indirect damage, obligation or expense due to complying with my request as given above. I shall be fully responsible and shall unconditionally compensate and indemnify the Bank in full. Signature Shareholder ( ) / / Bank Officer Number received Date / / Checker Remark Contact: Corporate Secretariat’s office of Standard Chartered Bank (Thai) Public Company Limited, Sathorn Nakorn Tower, 12th Floor, No. 100 North Sathorn Road, Silom, Bangrak, Bangkok, 10500 Thailand Telephone 66 2724 8041-42 Fax 66 2724 8044 Documents to be submitted for changing of dividend payment (All photocopies must be certified as true) For Individual Person 1. -

Gauging the Potential in Thai Banking* Introduction Overview

Financial Services Back on the investment radar: Gauging the potential in Thai banking* Introduction Overview The Thai banking sector is attracting increasing international • Economy set to rebound as confidence returns following interest as the market opens up to foreign investment and the return to democracy. the return to democracy helps to reinvigorate consumer • Banking sector recording steady growth. Strong confidence and demand. opportunities for the development of retail lending. Bad debt ratios have gradually declined and the balance • Foreign banks account for 12% of the market by assets and sheets of Thailand’s leading banks have strengthened 10% of lending by value.7 Strong presence in high-value considerably since the Asian financial crisis of 1997.1 niche segments including auto finance, mortgages and The moves to Basel II and IAS 39 are set to enhance credit cards. transparency and risk management within the sector, while accelerating the demand for foreign capital and expertise. • Organic entry strategies curtailed by licensing and branch opening restrictions. Reforms already in place include the ‘single presence’ rule, which by seeking to limit cross-ownership of the country’s • Acquisition of minority stakes in existing banks proving banks is leading to increased consolidation and the opening increasingly popular. Ceiling on foreign holdings set to be up of sizeable holdings for new investment. The Financial raised to 49%, though there are no firm plans to allow Sector Master Plan and forthcoming Financial Institution outright control. Business Act (2008), which will come into force in August • Demand for capital and foreign expertise is encouraging 2008, could ease restrictions on branch openings and the more domestic banks to seek foreign investment, especially size of foreign investment holdings. -

Notice of Additional Acquisition of Subsidiaries' Shares in Thailand

Notice of Additional Acquisition of Subsidiaries' Shares in Thailand TOKYO, February 28, 2020 -- Ajinomoto Co., Inc. (“Ajinomoto Co.”) has agreed with KASIKORNBANK PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED ("KBANK") and The Siam Commercial Bank Public Company Limited ("SCB") to acquire all the shares of AJINOMOTO CO., (Thailand) LTD. (“Ajinomoto Thailand”), owned by KBANK and SCB, following the resolution regarding the execution of share purchase and sale agreement with THANACHART SPV2 CO., Ltd. announced on January 31 2020. Today Ajinomoto Co. has resolved to enter into a share purchase and sale agreement with KBANK and SCB, respectively. 1. Reasons for Additional Acquisition of Shares Ajinomoto Thailand, established in 1960, is a consolidated subsidiary in which Ajinomoto Co. owns an 88.52% stake. It manufactures and sells seasonings, food products and other products in Thailand. Ajinomoto Co. set out "to consider increasing net income by increasing the ratio interest of consolidated subsidiaries" in the 2017-2019 (for 2020) Medium-Term Management Plan, and set out the basic policy of "concentrating all management resources for the purpose of solving food and health issues" in the "ASV Management of the Ajinomoto Group, Vision for 2030 and Medium-Term Management Plan for 2020-2025", released on February 19, 2020. Ajinomoto Co. will focus further management resources on solving food and health issues by raising the shareholding ratio of Ajinomoto Thailand, which is the mainstay of the consumer food business. Ajinomoto Co. also expects that the additional acquisition of such shares will contribute to the improvement of its ROE and EPS. Ajinomoto Co. will continue to strengthen our ability to generate cash flow and improve capital efficiency to increase shareholder value and transform our business structure into one capable of sustainable growth. -

Siam City Bank Public Company Limited

Tender Offer for Securities Of Siam City Bank Public Company Limited By The Offeror Thanachart Bank Public Company Limited 17 September 2010 – 19 November 2010 (Business day only) 9.00 a.m. – 4.00 p.m. Tender Offer Preparer and Agent Thanachart Securities Public Company Limited -Translation- TNS_IB 098/2010 14 September 2010 Subject : The submission of the Tender Offer Form for securities of Siam City Bank Public Company Limited To : The Secretary –General of the Office of the Securities and Exchange Commission The President of the Stock Exchange of Thailand The Directors and Shareholders of Siam City Bank Public Company Limited Enclosed : The tender offer form for securities of Siam City Bank Public Company Limited (Form 247-4) Pursuant to Thanachart Bank Public Company Limited (“Tender Offeror”) offers to tender securities of Siam City Bank Public Company Limited (“SCIB” or “the Company”) from all minority shareholders at the offer price of 32.50 Baht per share for the purpose of delist SCIB shares from listed securities in the Stock Exchange of Thailand. In addition, the Shareholders’ Meeting of SCIB has resolved to approve the delisting of securities of SCIB from listed securities in the Stock Exchange of Thailand on 5 August 2010 and the SET has approved an application for voluntary delisting of SCIB shares on 27 August 2010. Thanachart Securities Public Company Limited, a tender offer preparer, is pleased to submit the Tender Offer Form (Form 247-4) for securities of the Company to the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Stock Exchange of Thailand, the Company, and the Shareholders of the Company as a supporting document for consideration. -

Driving Investment, Trade and the Creation of Wealth Across Asia, Africa and the Middle East

Standard Chartered Bank (Thai) Pcl Annual Report 2014 Driving investment, trade and the creation of wealth across Asia, Africa and the Middle East sc.com/th About us What’s inside this report About Standard Chartered 2 We are a leading international banking group with more Overview than 90,000 employees representing 132 nationalities Performance highlights 4 operating in 71 markets. Chairman’s statement 6 Message from the President and CEO 8 We bank the people and companies driving investment, trade and the creation of wealth across Asia, Africa and the Middle East, where we earn around 90 per cent of our income and profits. Our heritage and values are expressed in our brand promise, Here for good. We provide a wide-range of products and services for personal and business clients across 70 markets. In 2014, we celebrated the Bank’s 120th anniversary in Thailand. Financial Summary of financial results 12 and operating Nature of business 14 review Sustainability 18 Awards & recognition Board of directors 22 Standard Chartered Bank (Thai) has been rated AAA Corporate (tha) for its national long-term rating by Fitch Ratings. governance Senior management 26 Organisation chart 30 SCBT was named the Best Foreign Commercial Bank in Thailand for the second consecutive year by Finance Structure of management 32 Asia. Internal controls 39 Corporate governance 40 Risk 44 Selection of directors and senior executives 48 Nomination and Compensation Committee report 49 Audit Committee report 50 Supplementary General Information 54 information Structure -

STOXX Asia 100 Last Updated: 03.07.2017

STOXX Asia 100 Last Updated: 03.07.2017 Rank Rank (PREVIOU ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) (FINAL) S) KR7005930003 6771720 005930.KS KR002D Samsung Electronics Co Ltd KR KRW Y 256.2 1 1 JP3633400001 6900643 7203.T 690064 Toyota Motor Corp. JP JPY Y 128.5 2 2 TW0002330008 6889106 2330.TW TW001Q TSMC TW TWD Y 113.6 3 3 JP3902900004 6335171 8306.T 659668 Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group JP JPY Y 83.5 4 4 HK0000069689 B4TX8S1 1299.HK HK1013 AIA GROUP HK HKD Y 77.2 5 5 JP3436100006 6770620 9984.T 677062 Softbank Group Corp. JP JPY Y 61.7 6 7 JP3735400008 6641373 9432.T 664137 Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C JP JPY Y 58.7 7 8 CNE1000002H1 B0LMTQ3 0939.HK CN0010 CHINA CONSTRUCTION BANK CORP H CN HKD Y 58.2 8 6 TW0002317005 6438564 2317.TW TW002R Hon Hai Precision Industry Co TW TWD Y 52.6 9 12 HK0941009539 6073556 0941.HK 607355 China Mobile Ltd. CN HKD Y 52.0 10 10 JP3890350006 6563024 8316.T 656302 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Grou JP JPY Y 48.3 11 15 INE040A01026 B5Q3JZ5 HDBK.BO IN00CH HDFC Bank Ltd IN INR Y 45.4 12 13 JP3854600008 6435145 7267.T 643514 Honda Motor Co. Ltd. JP JPY Y 43.3 13 14 JP3435000009 6821506 6758.T 682150 Sony Corp. JP JPY Y 42.3 14 17 JP3496400007 6248990 9433.T 624899 KDDI Corp. JP JPY Y 42.2 15 16 CNE1000003G1 B1G1QD8 1398.HK CN0021 ICBC H CN HKD Y 41.1 16 19 JP3885780001 6591014 8411.T 625024 Mizuho Financial Group Inc. -

Ar 18 Eng.Pdf

Our Vision: THE MOST ADMIRED BANK DIGITAL CONVENIENCE FOR EASIER LIVING Using advanced biometric technology for identity verification, the SCB EASY app lets new customers open a savings account by themselves anytime, anywhere. DIGITAL CONVENIENCE FOR EASIER LIVING Using advanced biometric technology for identity verification, the SCB EASY app lets new customers open a savings account by themselves anytime, anywhere. SMART DIGITAL LENDING FOR EVERYONE SCB EASY uses big data analytics to broaden customer access to personal loans and allow instant approval. SMART DIGITAL LENDING FOR EVERYONE SCB EASY uses big data analytics to broaden customer access to personal loans and allow instant approval. DIGITAL SOLUTIONS FOR THAI SMEs SCB brings street vendors into the “Industry 4.0” era. Our Total Business Solutions provides money management services for food cart franchisors and franchisees. DIGITAL SOLUTIONS FOR THAI SMEs SCB brings street vendors into the “Industry 4.0” era. Our Total Business Solutions provides money management services for food cart franchisors and franchisees. FINANCIAL LITERACY FOR ‘NEXT GEN’ THAIS “Keb Hom”, is an AI-based app that offers a model savings plan. This friendly yet powerful software helps young people learn financial discipline. FINANCIAL LITERACY FOR ‘NEXT GEN’ THAIS “Keb Hom”, is an AI-based app that offers a model savings plan. This friendly yet powerful software helps young people learn financial discipline. GOOD GOVERNANCE FOR A BETTER SOCIETY SCB emphasizes good corporate governance so that the Bank and society can both grow sustainably. It requires sound management, transparent processes and fairness. GOOD GOVERNANCE FOR A BETTER SOCIETY SCB emphasizes good corporate governance so that the Bank and society can both grow sustainably. -

Pakdee Paknara Partner

Pakdee Paknara Partner Pakdee is a Partner at The Capital Law Office with over 20 years of experience in mergers and acquisitions, power and energy projects, real estate and construction, property funds, international trade, telecommunications, computer technology and software licensing, government bidding and tax-related transactions. He has advised domestic and international clients on a wide variety of matters, and is specialized in preparation of documentation for complex commercial transactions, including supply, purchase and sale, service, management agency and employment agreements. Education M.Sc. in Taxation, Prior to joining The Capital Law Office in 2017, Pakdee was a partner of a Golden Gate University, 1994 leading law firm in Bangkok as a head of the commercial and international trade and tax practice. LL.B. Chulalongkorn University, 1987 Selected Transactional Experience Languages Mergers & Acquisitions Thai, English • Representing Thailand’s Government Savings Bank (GSB) in the Accolades sale of its 25% interest in issued share capital of Thanachart Fund M&A Management Company Limited (TFUND), to Prudential Corporation Highly Regarded by Holdings Limited (Prudential), an affiliate of Eastspring Investments IFLR1000 (2019-2020) (Singapore) Limited. At closing, GSB sold its TFUND 25% interest, and Thanachart Bank Public Company Limited (TBANK) sold its TFUND Leading Lawyer by 25.1% interest; Prudential owned 50.1% of TFUND, and TBANK IFLR1000 (2010-2016) retained a 49% interest. Transaction value: approximately THB 2.1 Leading Lawyer by billion (approximately USD 69.1 million). Asialaw Profiles 2016 • Representing Thanachart Capital Public Company Limited and Recommended Lawyer by Thanachart Bank Public Company Limited in a business merger Legal 500 Asia Pacific with TMB Bank Public Company Limited (TMB Bank) to become the th (2009-2014) 6 largest bank in Thailand. -

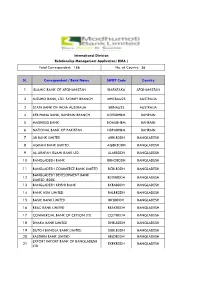

Sl. Correspondent / Bank Name SWIFT Code Country

International Division Relationship Management Application( RMA ) Total Correspondent: 156 No. of Country: 36 Sl. Correspondent / Bank Name SWIFT Code Country 1 ISLAMIC BANK OF AFGHANISTAN IBAFAFAKA AFGHANISTAN 2 MIZUHO BANK, LTD. SYDNEY BRANCH MHCBAU2S AUSTRALIA 3 STATE BANK OF INDIA AUSTRALIA SBINAU2S AUSTRALIA 4 KEB HANA BANK, BAHRAIN BRANCH KOEXBHBM BAHRAIN 5 MASHREQ BANK BOMLBHBM BAHRAIN 6 NATIONAL BANK OF PAKISTAN NBPABHBM BAHRAIN 7 AB BANK LIMITED ABBLBDDH BANGLADESH 8 AGRANI BANK LIMITED AGBKBDDH BANGLADESH 9 AL-ARAFAH ISLAMI BANK LTD. ALARBDDH BANGLADESH 10 BANGLADESH BANK BBHOBDDH BANGLADESH 11 BANGLADESH COMMERCE BANK LIMITED BCBLBDDH BANGLADESH BANGLADESH DEVELOPMENT BANK 12 BDDBBDDH BANGLADESH LIMITED (BDBL) 13 BANGLADESH KRISHI BANK BKBABDDH BANGLADESH 14 BANK ASIA LIMITED BALBBDDH BANGLADESH 15 BASIC BANK LIMITED BKSIBDDH BANGLADESH 16 BRAC BANK LIMITED BRAKBDDH BANGLADESH 17 COMMERCIAL BANK OF CEYLON LTD. CCEYBDDH BANGLADESH 18 DHAKA BANK LIMITED DHBLBDDH BANGLADESH 19 DUTCH BANGLA BANK LIMITED DBBLBDDH BANGLADESH 20 EASTERN BANK LIMITED EBLDBDDH BANGLADESH EXPORT IMPORT BANK OF BANGLADESH 21 EXBKBDDH BANGLADESH LTD 22 FIRST SECURITY ISLAMI BANK LIMITED FSEBBDDH BANGLADESH 23 HABIB BANK LTD HABBBDDH BANGLADESH 24 ICB ISLAMI BANK LIMITED BBSHBDDH BANGLADESH INTERNATIONAL FINANCE INVESTMENT 25 IFICBDDH BANGLADESH AND COMMERCE BANK LTD (IFIC BANK) 26 ISLAMI BANK LIMITED IBBLBDDH BANGLADESH 27 JAMUNA BANK LIMITED JAMUBDDH BANGLADESH 28 JANATA BANK LIMITED JANBBDDH BANGLADESH 29 MEGHNA BANK LIMITED MGBLBDDH BANGLADESH 30 MERCANTILE -

SECURITY Trustto TRUST

Vol. 19 No. 4 August 2020 `75 Pages 48 U GRO Capital pg 8 Bank of Maharashtra pg 27 SwissRe pg 30 Cosmos Bank pg 38 www.bankingfrontiers.com www.bankingfrontiers.live From SECURITY TRUSTto TRUST SECURITY Nagaraj Solkar Manish Pal Agnelo Dsouza Sridhara Sidhu PRESENTS MASTERCLASS CYBER INSURANCE - Demystifying the BLACK BOX DATE: 5th of September 2020 FACT SHEET `2.5cr siphoned off from Mumbai banks to phishing mails to steal credentials ___________________________ 900 Million ` Cyber attack on Cosmos bank Digitalization has entered all facets of our lives and Indian corporations ___________________________ are adopting technology in all their operations at lightning speed. However as they say everything comes with a price. In the case of 15 Billion technology, it is the fear of online data theft and other such cybercrimes. Loss by cyber attacks in BFSI Data is new oil and cyber attack is the new battlefield of the future. ___________________________ Cyber Insurance - The strongest protection against 500% losses of cyber attack. Estimated growth of cyber insurance By 5 major Prospective: Who will Benefit: PAYMENT DETAILS Details for RTGS or NEFT payment: u User perspective u MDs, CEOs, CXOs & Senior Company : Glocal Infomart Pvt Ltd Branch Place : Andheri East Account No. : 450301010036295 Branch City : Mumbai u Underwriter and Sales perspective Management Executives Bank Name : Union Bank of India Branch Code : 545031 u u Sales and Claims perspective CFOs & Senior Finance Executives Branch Name : Bhavani Nagar, Micra Code : 400026070 u u Legal Perspective CISOs Marol Maroshi IFSC Code : UBIN0545031 Pin Code : 400059 Swift Code : UBININBBGOR u Investigation Perspective u Underwriters u Risk Insurers u Liability Managers u Data Managers COURSE FEE For details please contact: Dhiraj Mestry : +91 77383 59665 `20,000 + 18% GST [email protected] SUNDER KRISHNAN JAYANT SARAN Arjun Bhaskaran N.S. -

Bank Announcement

BANK ANNOUNCEMENT Citibank, N.A., Bangkok Branch Detail concerning interest rates, service charges, fees and other expenses in the use of credit cards Effective from Sep 15, 2015 1. Interest, penalty, fee and other service charges Interest Maximum 20.00 % per annum Credit line usage fee ………-……..% per annum Penalty for overdue payment ………-……..% per annum Fees or other service charges ………-……..% per annum Commencing date for interest calculation From [ X ] date of payment to store [ ] date of summary of total transactions [ ] Due date for payment - Interest for revolving credit will be calculated starting from the posting date as indicated on the monthly statement. - Interest for cash advance will be calculated starting from the withdrawal date to the date on which Citibank has received payment in full. 2. Minimum installment payment rate 10% of the total amount as per the monthly statement, or minimum payment of Baht 200 whichever is higher (The minimum payment 200 Baht is not applied to transaction from PayLite, PayLite Conversion On Phone/ Online, or Cash Advance On Phone/ Online programs, that required monthly minimum payment is 10% of outstanding balance as of statement cycle date). 3. Cash withdrawal fee 3 % of the amount of cash withdrawn (Cash Advance withdrawal amount shall vary with customer's payment history to be up to 100% of credit line) 4. Interest-free repayment period if paying when due Maximum payment period up to 45 - 55 days from statement billing cycle (Fully paying on due for retail spending) (Maximum payment period up to 55 days for Citibank Visa / Master and Citibank Rewards (Limited Edition)) 5.