W O Rld O F a Rt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proyecto Arqueológico Lago De Atitlán

PROYECTO ARQUEOLÓGICO LAGO DE ATITLÁN RECONOCIMIENTO EN LA ORILLA OESTE DEL LAGO ATITLÁN, TEMPORADA 2015 TOMO 3: CERAMICA, ARTEFACTOS Y MONUMENTOS Gavin R. Davies, Director, Universidad de Kentucky María de los Ángeles Corado Mena, Codirectora Universidad del Valle de Guatemala CONTENIDO LISTA DE Tablas y Figuras ................................................................................................. 3 15. CERÁMICA Y CRONOLOGÍA ....................................................................................... 5 15.1 PRECLáSICO MEDIO A TARDíO (c. 400 AC – 0 Dc) ............................................. 5 GRUPO: CAFÉ PULIDO .................................................................................................. 6 GRUPO: NEGRO Y CAFÉ-NEGRO ................................................................................... 6 GRUPO: ROJO SOBRE CREMA ....................................................................................... 7 GRUPO: ZONADO PRECLÁSICO..................................................................................... 7 GRUPO: SAN JUAN LOCAL .......................................................................................... 10 TIPOS PRECLASICOS NO DEFINIDOS ........................................................................... 11 15.2 EL PROTOCLÁSICO (100 DC – 300 dc) .............................................................. 12 GRUPO: NEGRO PULIDO ............................................................................................ 12 GRUPO: CAFÉ-NEGRO PRECLÁSICO -

Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press

UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Title Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America: An Annotated Bibliography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/68r4t3dq ISBN 978-1-938770-25-8 Publication Date 1979 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are within the manuscript. Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America: An Annotated Bibliography Second, Revised Edition Matthias Strecker MONOGRAPHX Institute of Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America: An Annotated Bibliography Second, Revised Edition Matthias Strecker MONOGRAPHX Institute of Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles ' eBook ISBN: 978-1-938770-25-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE By Brian D. Dillon . 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vi INTRODUCTION . 1 PART I: BIBLIOGRAPHY IN GEOGRAPHICAL ORDER 7 Tabasco and Chiapas . 9 Peninsula of Yucatan: C ampeche, Yucatan, Quintana Roo, Belize 11 Guatemala 13 El Salvador 15 Honduras 17 Nicaragua 19 Costa Rica 21 Panama 23 PART II: BIBLIOGRAPHY BY AUTHOR 25 NOTES 81 PREFACE Brian D. Dillon Matthias Strecker's Rock Art of East Mexico and Central America: An Annotated Bibliography originally appeared as a small edition in 1979 and quickly went out of print. Because of the volume of requests for additional copies and the influx of new or overlooked citations received since the first printing, production of a second , revised edition became necessary. More than half a hundred new ref erences in Spanish, English, German and French have been incorporated into this new edition and help Strecker's work to maintain its position as the most comprehen sive listing of rock art studies undertaken in Central America. -

Megaliths and the Early Mezcala Urban Tradition of Mexico

ICDIGITAL Separata 44-45/5 ALMOGAREN 44-45/2013-2014MM131 ICDIGITAL Eine PDF-Serie des Institutum Canarium herausgegeben von Hans-Joachim Ulbrich Technische Hinweise für den Leser: Die vorliegende Datei ist die digitale Version eines im Jahrbuch "Almogaren" ge- druckten Aufsatzes. Aus technischen Gründen konnte – nur bei Aufsätzen vor 1990 – der originale Zeilenfall nicht beibehalten werden. Das bedeutet, dass Zeilen- nummern hier nicht unbedingt jenen im Original entsprechen. Nach wie vor un- verändert ist jedoch der Text pro Seite, so dass Zitate von Textstellen in der ge- druckten wie in der digitalen Version identisch sind, d.h. gleiche Seitenzahlen (Pa- ginierung) aufweisen. Der im Aufsatzkopf erwähnte Erscheinungsort kann vom Sitz der Gesellschaft abweichen, wenn die Publikation nicht im Selbstverlag er- schienen ist (z.B. Vereinssitz = Hallein, Verlagsort = Graz wie bei Almogaren III). Die deutsche Rechtschreibung wurde – mit Ausnahme von Literaturzitaten – den aktuellen Regeln angepasst. Englischsprachige Keywords wurden zum Teil nach- träglich ergänzt. PDF-Dokumente des IC lassen sich mit dem kostenlosen Adobe Acrobat Reader (Version 7.0 oder höher) lesen. Für den Inhalt der Aufsätze sind allein die Autoren verantwortlich. Dunkelrot gefärbter Text kennzeichnet spätere Einfügungen der Redaktion. Alle Vervielfältigungs- und Medien-Rechte dieses Beitrags liegen beim Institutum Canarium Hauslabgasse 31/6 A-1050 Wien IC-Separatas werden für den privaten bzw. wissenschaftlichen Bereich kostenlos zur Verfügung gestellt. Digitale oder gedruckte Kopien von diesen PDFs herzu- stellen und gegen Gebühr zu verbreiten, ist jedoch strengstens untersagt und be- deutet eine schwerwiegende Verletzung der Urheberrechte. Weitere Informationen und Kontaktmöglichkeiten: institutum-canarium.org almogaren.org Abbildung Titelseite: Original-Umschlag des gedruckten Jahrbuches. -

The Toltec Invasion and Chichen Itza

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: Breaking the Maya Code Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs Angkor and the Khmer Civilization India: A Short History The Incas The Aztecs See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com 7 THE POSTCLASSIC By the close of the tenth century AD the destiny of the once proud and independent Maya had, at least in northern Yucatan, fallen into the hands of grim warriors from the highlands of central Mexico, where a new order of men had replaced the supposedly more intellectual rulers of Classic times. We know a good deal about the events that led to the conquest of Yucatan by these foreigners, and the subsequent replacement of their state by a resurgent but already decadent Maya culture, for we have entered into a kind of history, albeit far more shaky than that which was recorded on the monuments of the Classic Period. The traditional annals of the peoples of Yucatan, and also of the Guatemalan highlanders, transcribed into Spanish letters early in Colonial times, apparently reach back as far as the beginning of the Postclassic era and are very important sources. But such annals should be used with much caution, whether they come to us from Bishop Landa himself, from statements made by the native nobility, or from native lawsuits and land claims. These are often confused and often self-contradictory, not least because native lineages seem to have deliberately falsified their own histories for political reasons. Our richest (and most treacherous) sources are the K’atun Prophecies of Yucatan, contained in the “Books of Chilam Balam,” which derive their name from a Maya savant said to have predicted the arrival of the Spaniards from the east. -

Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts

Guide to Research at Hirsch Library Pre-Columbian, Mesoamerican Art & Artifacts Before researching a work of art from the MFAH collection, the work should be viewed in the museum, if possible. The cultural context and descriptions of works in books and journals will be far more meaningful if you have taken advantage of this opportunity. Most good writing about art begins with careful inspections of the objects themselves, followed by informed library research. If the project includes the compiling of a bibliography, it will be most valuable if a full range of resources is consulted, including reference works, books, and journal articles. Listing on-line sources and survey books is usually much less informative. To find articles in scholarly journals, use indexes such as Art Abstracts or, the Bibliography of the History of Art. Exhibition catalogs and books about the holdings of other museums may contain entries written about related objects that could also provide guidance and examples of how to write about art. To find books, use keywords in the on-line catalog. Once relevant titles are located, careful attention to how those items are cataloged will lead to similar books with those subject headings. Footnotes and bibliographies in books and articles can also lead to other sources. University libraries will usually offer further holdings on a subject, and the Electronic Resources Room in the library can be used to access their on-line catalogs. Sylvan Barnet’s, A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 6th edition, provides a useful description of the process of looking, reading, and writing. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

**Hay Referencia a 1 Figura, Con Listado Al Final

Vidal Lorenzo, Cristina 1998 Tikal, un siglo de arqueología. En XI Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1997 (editado por J.P. Laporte y H. Escobedo), pp.5-9. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala (versión digital). 2 TIKAL, UN SIGLO DE ARQUEOLOGÍA Cristina Vidal Lorenzo "Tikal, un siglo de arqueología" es el título de una exposición monográfica, en la que hemos pretendido reunir las imágenes más representativas del descubrimiento, excavación y restauración de esta importante ciudad de la antigüedad Maya. En realidad, la exposición está concebida como un paseo a través de las intervenciones a las que fueron sometidos sus edificios principales a lo largo de estos últimos cien años. Para ello, hubo que recurrir a las excelentes fotografías tomadas por los incansables exploradores y viajeros del siglo XIX, los primeros que dieron a conocer los vestigios de una ciudad que había permanecido más de mil años sepultada por la selva. Nos referimos a las célebres imágenes captadas por A. Maudslay y T. Maler a finales del siglo pasado, cuyas placas de vidrio originales se conservan en el Museo Británico y en el Museo Peabody de la Universidad de Harvard, respectivamente, No es nuestra intención relatar ahora cómo se llevaron a cabo tales trabajos -información contenida en los paneles explicativos de la muestra- pero sí nos gustaría realizar una pequeña reflexión acerca del impacto que tuvo en la arquitectura de Tikal todo este cúmulo de actuaciones. Deberíamos empezar por su descubrimiento en 1848, ya que con ocasión de esa expedición se cortaron muchos árboles y se despejó parte de la espesa maleza en la que estaban sumergidas las ruinas, con el fin de realizar los primeros dibujos hasta ahora conocidos de Tikal, a cargo del artista Eusebio Lara. -

Complete Inventory

Maya Ethnobotany Complete Inventory of plants 1 Fifth edition, November 2011 Maya Ethnobotany Complete Inventory:: fruits,nuts, root crops, grains,construction materials, utilitarian uses, sacred plants, sacred flowers Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, Honduras Nicholas M. Hellmuth Maya Ethnobotany Complete Inventory of plants 2 Introduction This opus is a progress report on over thirty years of studying plants and agriculture of the present-day Maya with the goal of understanding plant usage by the Classic Maya. As a progress report it still has a long way to go before being finished. But even in its unfinished state, this report provides abundant listings of plants in a useful thematic arrangement. The only other publication that I am familiar with which lists even close to most of the plants utilized by the Maya is in an article by Cyrus Lundell (1938). • Obviously books on Mayan agriculture should have informative lists of all Maya agricultural crops, but these do not tend to include plants used for house construction. • There are monumental monographs, such as all the trees of Guatemala (Parker 2008) but they are botanical works, not ethnobotanical, and there is no cross-reference by kind of use. You have to go through over one thousand pages and several thousand tree species to find what you are looking for. • There are even important monographs on Maya ethnobotany, but they are usually limited to one country, or one theme, often medicinal plants. • There are even nice monographs on edible plants of Central America (Chízmar 2009), but these do not include every local edible plant, and their focus is not utilitarian plants at all, nor sacred plants. -

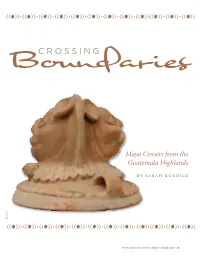

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Una Revision Preliminar De La Historia De Abaj Takalik

Popenoe de Hatch, Marion y Christa Schieber de Lavarreda 2001 Una revisión preliminar de la historia de Tak´alik Ab´aj, departamento de Retalhuleu. En XIV Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2000 (editado por J.P. Laporte, A.C. Suasnávar y B. Arroyo), pp.990-1005. Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, Guatemala (versión digital). 77 UNA REVISIÓN PRELIMINAR DE LA HISTORIA DE TAK´ALIK AB´AJ, DEPARTAMENTO DE RETALHULEU Marion Popenoe de Hatch Christa Schieber de Lavarreda Nuestras recientes investigaciones en Tak´alik Ab´aj se han dirigido hacia resolver una serie de preguntas que nos han interesado por largo tiempo. Este año hemos dirigido nuestra atención a la pregunta más intrigante de todas. En algún momento durante la historia de Tak´alik Ab´aj ocurrió un incidente violento. Muchos de los monumentos de gran tamaño, especialmente los esculpidos en estilo Maya, fueron tirados y destruidos. ¿Quién fue responsable de la violencia en Tak´alik Ab´aj, destruyendo deliberadamente los monumentos, y cuándo ocurrió este evento? Creemos que tenemos la respuesta a esta pregunta y presentaremos el argumento en breve. Otras preguntas que hemos tenido son las siguientes: ¿Quiénes fueron los primeros habitantes de Tak´alik Ab´aj?; ¿Por qué fundaron el sitio en el lugar donde se encuentra?; ¿Cuál era la función de Tak´alik Ab´aj?; ¿Cuántos complejos cerámicos, que representan distintas poblaciones, pueden identificarse a lo largo de la historia de Tak´alik Ab´aj y qué papel jugaron?; ¿Qué cerámica está asociada con las esculturas Olmecas y cuál corresponde a las esculturas Mayas?; ¿Qué relaciones mantuvo Tak´alik Ab´aj con otras regiones a lo largo del tiempo?; ¿Cómo se manifiestan los periodos Preclásico, Clásico y Postclásico en Tak´alik Ab´aj, y cómo están relacionados? Hace un año en este Simposio (Popenoe de Hatch et al. -

Canuto-Et-Al.-2018.Pdf

RESEARCH ◥ shows field systems in the low-lying wetlands RESEARCH ARTICLE SUMMARY and terraces in the upland areas. The scale of wetland systems and their association with dense populations suggest centralized planning, ARCHAEOLOGY whereas upland terraces cluster around res- idences, implying local management. Analy- Ancient lowland Maya complexity as sis identified 362 km2 of deliberately modified ◥ agricultural terrain and ON OUR WEBSITE another 952 km2 of un- revealed by airborne laser scanning Read the full article modified uplands for at http://dx.doi. potential swidden use. of northern Guatemala org/10.1126/ Approximately 106 km science.aau0137 of causeways within and .................................................. Marcello A. Canuto*†, Francisco Estrada-Belli*†, Thomas G. Garrison*†, between sites constitute Stephen D. Houston‡, Mary Jane Acuña, Milan Kováč, Damien Marken, evidence of inter- and intracommunity con- Philippe Nondédéo, Luke Auld-Thomas‡, Cyril Castanet, David Chatelain, nectivity. In contrast, sizable defensive features Carlos R. Chiriboga, Tomáš Drápela, Tibor Lieskovský, Alexandre Tokovinine, point to societal disconnection and large-scale Antolín Velasquez, Juan C. Fernández-Díaz, Ramesh Shrestha conflict. 2 CONCLUSION: The 2144 km of lidar data Downloaded from INTRODUCTION: Lowland Maya civilization scholars has provided a unique regional perspec- acquired by the PLI alter interpretations of the flourished from 1000 BCE to 1500 CE in and tive revealing substantial ancient population as ancient Maya at a regional scale. An ancient around the Yucatan Peninsula. Known for its well as complex previously unrecognized land- population in the millions was unevenly distrib- sophistication in writing, art, architecture, as- scape modifications at a grand scale throughout uted across the central lowlands, with varying tronomy, and mathematics, this civilization is the central lowlands in the Yucatan peninsula. -

CATALOG Mayan Stelaes

CATALOG Mayan Stelaes Palos Mayan Collection 1 Table of Contents Aguateca 4 Ceibal 13 Dos Pilas 20 El Baúl 23 Itsimite 27 Ixlu 29 Ixtutz 31 Jimbal 33 Kaminaljuyu 35 La Amelia 37 Piedras Negras 39 Polol 41 Quirigia 43 Tikal 45 Yaxha 56 Mayan Fragments 58 Rubbings 62 Small Sculptures 65 2 About Palos Mayan Collection The Palos Mayan Collection includes 90 reproductions of pre-Columbian stone carvings originally created by the Mayan and Pipil people traced back to 879 A.D. The Palos Mayan Collection sculptures are created by master sculptor Manuel Palos from scholar Joan W. Patten’s casts and rubbings of the original artifacts in Guatemala. Patten received official permission from the Guatemalan government to create casts and rubbings of original Mayan carvings and bequeathed her replicas to collaborator Manuel Palos. Some of the originals stelae were later stolen or destroyed, leaving Patten’s castings and rubbings as their only remaining record. These fine art-quality Maya Stelae reproductions are available for purchase by museums, universities, and private collectors through Palos Studio. You are invited to book a virtual tour or an in- person tour through [email protected] 3 Aguateca Aguateca is in the southwestern part of the Department of the Peten, Guatemala, about 15 kilometers south of the village of Sayaxche, on a ridge on the western side of Late Petexbatun. AGUATECA STELA 1 (50”x85”) A.D. 741 - Late Classic Presumed to be a ruler of Aguatecas, his head is turned in an expression of innate authority, personifying the rank implied by the symbols adorning his costume.