Igda Finland Hubs and Their Effects on Local Game Development: an Ethnographic Study of Tampere and Kajaani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vysok´E Uˇcení Technick´E V Brnˇe Grafick´E Intro Do

VYSOKEU´ CENˇ ´I TECHNICKE´ V BRNEˇ BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY FAKULTA INFORMACNˇ ´ICH TECHNOLOGI´I USTAV´ POCˇ ´ITACOVˇ E´ GRAFIKY A MULTIMEDI´ ´I FACULTY OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER GRAPHICS AND MULTIMEDIA GRAFICKE´ INTRO DO 64KB S POUZITˇ ´IM OPENGL GRAPHIC INTRO 64KB USING OPENGL DIPLOMOVA´ PRACE´ MASTER’S THESIS AUTOR PRACE´ PAVEL GUNIA AUTHOR VEDOUC´I PRACE´ Ing. ADAM HEROUT, Ph.D. SUPERVISOR BRNO 2007 Abstrakt Tato pr´acepojedn´av´ao fenom´enu grafick´eho intra, ˇcasto oznaˇcovan´emjako digit´aln´ıgraffiti. Detailnˇese rozebere t´ema grafick´ehointra s omezenou velikost´ıa pop´ıˇs´ıse techniky vhodn´e k jeho realizaci. Na konci pr´acejsou diskutov´any postˇrehy a zkuˇsenosti z´ıskan´ebˇehem tvorby, stejnˇetak i celkov´eshrut´ıa pohled do budoucna. Kl´ıˇcov´aslova poˇc´ıtaˇcov´agrafika, digit´aln´ıumˇen´ı,demo, intro, OpenGL, procedur´aln´ıgenerov´an´ı,komp- rese, parametrick´ekˇrivky, parametrick´eplochy, syntetizovan´ahudba Abstract This work deals with the phenomenon of graphic intros, a digital graffiti of the modern age. The focus is put on size restricted animation of size of the executable file lower than 64 kilobytes. It reveals the main techniques used. Finally, interesting aspects and experiences that came up are discussed, as well as the conclusion and future work proposal. Keywords computer graphics, digital art, demo, intro, OpenGL, procedural generation, compression, parametric curve, parametric surface, synthetized music Citace Pavel Gunia: Graphic intro 64kB using OpenGL, diplomov´apr´ace, Brno, FIT VUT v Brnˇe, 2007 Graphic intro 64kB using OpenGL Prohl´aˇsen´ı Prohlaˇsuji, ˇzejsem tuto diplomovou pr´aci vypracoval samostatnˇepod veden´ımpana Ing. -

A Brief History of the Russian Spectrum Demoscene

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE RUSSIAN Allegedly, engineers from the Ukrainian city Lvov, were the first to succeed with this challenge and built a working machine SPECTRUM DEMOSCENE in August 1985. Their own designed schematics became very BY ELFH OF INWARD AND CYBERPUNKS UNITY valuable information, so they could trade it to the researchers in other cities for knowledge on other topics. Still, this remained Relations between Soviet Russia and computers were always nents – more than 200 to be precise. This fact complicated the unknown to the wider public and only a limited amount of peo- a bit obscure, especially when it comes to foreign models that possibility for average Radio readers to build the “Micro-80”, ple actually knew about the existence of a cheap home com- were not officially imported here. But, if one wants to trace the because a lot of elements were hard to find in normal stores, puter with colourful graphics, which any Radio amateur could roots of the Russian demoscene, especially on the Spectrum, and in most cases could only be found on the black market. easily build at home. For example, in 1986 “Radio” magazine you must dig deep into the 1980’s, when the first generation of was still publishing the schematics of the Radio-86RK compu- radio amateurs built their first machines themselves. ter, which consisted of 29 parts, but had only a black and white A LOT OF ELEMENTS WERE HARD text mode display. CONTRABAND COMPUTERS TO FIND IN NORMAL STORES, ONLY The main role in this development was played by a very popu- ON THE BLACK MARKET Despite this, it first became a very popular machine in Rus- lar magazine named “Radio”, which gathered a lot of talented sia. -

Download the Pdf Here

of people who got together through Bulletin Board Systems, THE PORTUGUESE DEMOSCENE Reckless Life BBS and Infinity BBS run by the infamous Captain Hook. The scene thrived through the nineties with the uprising HISTORY of IRC and the two issues of the diskmag, Infinity, put together BY PS OF TPOLM by Garfield, VAngel and Spellcaster if my memory serves me correctly. The first documented demoscene event in Portugal The Portuguese demoscene, as most Portuguese technology, ducing cheap labour for English-owned factories of the ZX Sin- was organized in 1996 and was called the Virtual Music Con- is a fluke of chance. For many years, Portugal held last place clair Spectrum family of machines. While kids in Central and test. It was just a simple tracking competition. Groups formed among Europe’s nations in iliteracy per capita and emigration. Northern Europe were playing with their Commodores and around this time were Radioactive Design (RD) with Garfield, Certified higher education for new technologies and arts has Ataris during the late eighties, in Portugal we were consuming only been institutionalized within the last 10 years. Even large Spectrum magnetic tapes. WHILE KIDS IN CENTRAL volume capitalist markets, such as the videogame industry, AND NORTHERN EUROPE are still in their infancy in Portugal. It has only been six years, THE BIRTH OF THE PORTUGUESE at most, since serious full time jobs became available in the WERE PLAYING WITH THEIR business. In fact Portugal is a country that mostly imports and DEMOSCENE COMMODORES AND ATARIS, IN consumes technology (2.5 cellphones per person on average) The first known demo made by a Portuguese demoscener was PORTUGAL WE WERE CONSUMING instead of developing and exporting it. -

Text of the German Application of Art of Coding

This is the Text of the German application of Art of Coding (www.http://demoscene-the-art-of-coding.net) with the purpose of bringing the demoscene onto the list of UNESCO intangible cultural heritage of humanity. The application was submitted in Oct 2019 and has been written in an collaborative community effort led by Tobias Kopka supported by Andre Kudra, Stephan Maienhöfer, Gleb Albert, Christian Brandt, Andreas Lange and many more who gave their hands at Digitale Kultur und Tastatur und Maus e.V. The structure depends on the form, which is given by the German UNESCO. In spite the structure differs from forms used in other countries text modules can be used for application in other countries. The texts in square brackets are part of the German form. Also every kind of feedback is welcome, which could be taken into account for future use. Use ‘team (at) demoscene-the-art-of-coding.net’ 1. Type of Immaterial Cultural Heritage [Please tick the applicable sections and elaborate in keywords (multi-selection possible, but not mandatory)] Section A) verbally passed on traditions and expressions [keywords]: own technical vocabulary, own idiom with specialized terminology, English is lingua franca Section B) performing arts (music, theatre, dance) [keywords]: composition, performant, live, public presentation, animation Section C) social tradition, (seasonal) celebration and ritual [keywords]: demoparties, competitions, visitor voting, price ceremonies Section D) Knowledge and customs, related to nature or the universe [keywords]: digitalized living environment, cyberspace, virtual reality Section E) traditional craftsmanship [keywords]: coding, composition, animation, adoption, do-it-yourself Section F) other 2. -

Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick?

AALTO UNIVERSITY School of Science and Technology Faculty of Information and Natural Sciences Department of Media Technology Markku Reunanen Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick? Licentiate Thesis Helsinki, April 23, 2010 Supervisor: Professor Tapio Takala AALTO UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT OF LICENTIATE THESIS School of Science and Technology Faculty of Information and Natural Sciences Department of Media Technology Author Date Markku Reunanen April 23, 2010 Pages 134 Title of thesis Computer Demos—What Makes Them Tick? Professorship Professorship code Contents Production T013Z Supervisor Professor Tapio Takala Instructor - This licentiate thesis deals with a worldwide community of hobbyists called the demoscene. The activities of the community in question revolve around real-time multimedia demonstrations known as demos. The historical frame of the study spans from the late 1970s, and the advent of affordable home computers, up to 2009. So far little academic research has been conducted on the topic and the number of other publications is almost equally low. The work done by other researchers is discussed and additional connections are made to other related fields of study such as computer history and media research. The material of the study consists principally of demos, contemporary disk magazines and online sources such as community websites and archives. A general overview of the demoscene and its practices is provided to the reader as a foundation for understanding the more in-depth topics. One chapter is dedicated to the analysis of the artifacts produced by the community and another to the discussion of the computer hardware in relation to the creative aspirations of the community members. -

TIMES of CHANGE in the DEMOSCENE a Creative Community and Its Relationship with Technology

TIMES OF CHANGE IN THE DEMOSCENE A Creative Community and Its Relationship with Technology Markku Reunanen ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Turku, for public examination in Classroom 125 University Consortium of Pori, on February 17, 2017, at 12.00 TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS Sarja - ser. B osa - tom. 428 | Humanoria | Turku 2017 TIMES OF CHANGE IN THE DEMOSCENE A Creative Community and Its Relationship with Technology Markku Reunanen TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS Sarja - ser. B osa - tom. 428 | Humanoria | Turku 2017 University of Turku Faculty of Humanities School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Degree Programme in Cultural Production and Landscape Studies Digital Culture, Juno Doctoral Programme Supervisors Professor Jaakko Suominen University lecturer Petri Saarikoski University of Turku University of Turku Finland Finland Pre-examiners Professor Nick Montfort Associate professor Olli Sotamaa Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Tampere United States Finland Opponent Assistant professor Carl Therrien University of Montreal Canada The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. ISBN 978-951-29-6716-2 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-6717-9 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987 (PRINT) ISSN 2343-3191 (ONLINE) Cover image: Markku Reunanen Juvenes Print, Turku, Finland 2017 Abstract UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Faculty of Humanities School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Degree Programme in Cultural Production and Landscape Studies Digital Culture REUNANEN, MARKKU: Times of Change in the Demoscene: A Creative Commu- nity and Its Relationship with Technology Doctoral dissertation, 100 pages, 88 appendix pages January 17, 2017 The demoscene is a form of digital culture that emerged in the mid-1980s after home computers started becoming commonplace. -

Demoscene No Brasil: Um Mapeamento Quasi-Sistem´Aticoda Literatura

Demoscene no Brasil: Um Mapeamento Quasi-Sistem´aticoda Literatura Demoscene in Brazil: A Quasi-Systematic Mapping Study Joenio Marques da Costa Universidade de Bras´ılia,MediaLab/UnB 21 de mar¸code 2021 Resumo Esta pesquisa investiga a comunidade brasileira de demoscene e responde a quest~oessobre o n´ıvel de atividade no Brasil, produ¸c~aode demos, realiza¸c~aode eventos, n´umerode praticantes e outros aspectos da cena local, al´emde trazer dados sobre o volume de pesquisas no Brasil neste cen´ario. O estudo ´e realizado atrav´esde uma revis~aode literatura, incluindo literatura acad^emicae literatura cinza sobre demoscene no Brasil ou publicado no Brasil em portugu^es, a busca por literatura foi realizada em portais acad^emicoscomo Peri´odicosCapes, Google Scholar, ACM Digital Library, entre outros e tamb´emem portais de busca web como Google Search, Yahoo Search e DuckDuckGo Search, a coleta de dados foi realizada em novembro de 2019 e encontrou um total de 117 resultados, a an´alisedos dados extra´ıdosda literatura mostra que apesar de existir participa¸c~aobrasileira na produ¸c~aode demos e na realiza¸c~aode eventos, especialmente nos anos 1990, e posteriormente em 2012 e 2017, a atividade no Brasil ´ebastante errante e inst´avel, com momentos de produ¸c~aoseguido por enormes espa¸cosde total inatividade, indicando uma quase inexist^enciade comunidade local, o estudo apresenta n´umeros,nomes e refer^enciaspara toda a produ¸c~aobrasileira, e por fim conclui tamb´emn~aohaver pesquisas sobre demoscene no Brasil, fazendo deste estudo uma iniciativa in´editasobre o tema. -

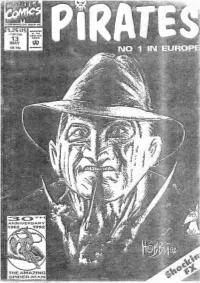

PIRATES #13' Available, Just Send Us 0 Blank VHS Lope

?5US .... i,50t:AN .... TM • COMICI 13 co •• MAY eN UK 70., I' I . J• • .: 1 : ;,r," .J • THEAMAZING SPIDER-M.o.N Deor Soilors, We finolly sobered up after the hugo success of our lalesl trip 10 Allanlis III We sel course for onolher deslinotion but unknown 11 Meanwhile we celebraled Easier and ore heading for X-MAS I11 We also welcome our lolest crew member, IRON MAIDEN which will hopefully be a greol conlribution to our si off I11 We must also thank our compalriols oul Ihere on the wide ocean far supporting us on our dangerous journeys and for sending re-enforcements 011 Ihe time ..... Well so for '92 has been a remarkable year I11 2 issues of Pirales in less then 6 monlhs, Thor got follerJn even more slupid, DOM hod 2 firsl-releases in Ihe losl 12 monlhs and our ship hosn'l sunk yel IIIII Slill due 10 some heavy slorm weolher some of the infonnalian ended up being losllll So you'll find an page 1 4 a photo of Sauron/lls and his brother (not Fist/lis) and on page 15 Ihe lop piccie is okoz Jock Droopis/DOM. And please nalice that the crew-members are nol respansable for evenluol depressions or suicide a!lempts after completing this issue .... See you on our nexl trip, RED-BEARD Tecllnical realisolion details: Original ideo by JUMPIE/ex-F4CG and SOlAR/F4CG Equipment used 386 DX, MPS 1200, Loserprinter, Super zoom copymachine,Scissors, super gh)e and ono box of DUREX condoms during Ihe process phala's copied by BOD/TALENT Typing done by SOlAR/F4CG and SCORPIE/F4CG Articles: Pirales crew and Rough/Chromance Graphics : Habbit,OMG,Golcha,Scorpie/F4CG,Redstar/LOGIC,Mirage/LEGEND Ediling help: Ninja,Kid/F4CG,Salar/F4CG,Scorpie/F4CG VHS lope 'The making of PIRATES #13' available, just send us 0 blank VHS lope. -

Jahresbericht Annual Report

Jahresbericht 2006 Annual Report Das Jahr 2006 war ein er- folgreiches Jahr, klare Ziele bestimmten die Aktivitäten des Vereins. Die Evoke im Sommer war hierbei unser größtes Projekt. Darüber hinaus konnten wir mit der Breakpoint und der tUM zwei weitere Demoparties in Deutschland unterstüt- zen. Auch das Echtzeit Film Festival setzte wieder auf unsere Kompetenz in Sachen Demoszene. Gefragt war unsere Erfahrung zu- dem bei einem Vortrag über die Demoszene in New York. Ganz neue Wege gingen wir mit einem reinen Online- Wettbewerb, der Intel Demo Trailer Competition, an der einige der besten Demo- gruppen teilnahmen. Unsere Aktivitäten sorgten 2006 für ein großes Medienecho, der Verein war an Beiträgen über die Demoszene in Print, Ra- Vorwort / Preamble dio und Fernsehen beteiligt. Für den Vorstand, Stefan Keßeler 03 2006 was a successful year, clearly defined objectives specified the associations activities. This summers edition of Evoke proved to be the biggest project. Ad- ditional support was given to two other demoparties, Breakpoint and tUM. The Echtzeit Film Festival once again relied on our expertise in all things demoscene. Also useful was our expe- rience at a presentation about the demoscene in New York. A whole new direction was taken in an online only competition, the Intel Demo Trailer Competi- tion, featuring some of the best demogroups around. Our activities during 2006 garnered a lot of media ap- pearences, the association was involved in print, radio and TV segments about the demoscene. For the executive committe, Stefan Keßeler Page „Eine kleine, sehr lebendige Szene von Programmierern, Designern und Musikern befasst sich seit Jahren nahezu unbe- merkt mit der Entwicklung ganz besonderer digitaler Artworks in Form von Echtzeitpro- grammen — von Demos.” Das führende Magazin für kreatives Medien design, Publishing und Trends widmet sich in der ersten Ausgabe 2006 der Demo szene. -

08. Japanese Demo Scene � �Got, Fri 31 Aug 2007 � �Japanese Demo Scene

http://www.bitfellas.org/e107_plugins/content/content.php?content.513 Page 1/4 08. Japanese Demo Scene Got, Fri 31 Aug 2007 Japanese Demo Scene By Got/Eldorado & Adok/Hugi The beginning of the demoscene in Japan was when Yukinori Yamazaki got his hands on demos from Future Crew. That was back in the year 1995. He founded a demo group named "Golden Weed Project". Soon after that, the group released their first (and only) demo. A year later, Hideo Ikeuchi founded a demogroup named "A20". Their first demo was released at the first online demo party in Japan - Horic96. A20 remained active until about 1998; however, nowadays it is inactive. Another group was active around 1997. It was called "Radium Software". They released two demos. Their member "^c" was in charge of code, gfx and sfx, and released the demo. More recently, he entered the Music Compo at 2chparty01 with about five entries. The site, 2chparty, is still active. There's also a related community site called "2channel", which is now famous in the Japanese scene. There was a thread about "mega demos"; it's basically the people who contributed to this thread that make up today's Japanese demo scene - members of eldorado, SystemK, 301, n.h.k., viep, volvox and other groups. Trends In the years 1995 to 2000, the demos focused on software rendering. At the beginnng of the 21st century, eldorado released an accelerated demo using OpenGL. In general, game making is very popular in Japan, whilst demo making is not that popular yet. However, it has gradually begun to improve in recent years. -

Printable PDF Version

Four Kilobyte Art Markku Reunanen Lecturer [email protected] Aalto University School of Art and Design First published in Finnish in WiderScreen 2–3/2013 as ”Neljän kilotavun taide”. Abstract The socalled 4k intros are realtime audiovisual presentations that fit in four kilobytes. They have mostly been created by the demoscene, a technicallyoriented community that emerged in the mid1980s. In this article I study the history and cultural importance of 4k intros as a marginal form of digital art. Keywords: 4k intros, algorithmic art, demoscene, programming Introduction Two to the power of twelve, 4096 bytes, is a tiny amount of data: approximately as much as a row of pixels on a computer screen or a page of text. These days, when applications and media files consume gigabytes of disk space, it might be hard to think that one could fit something meaningful in just four kilobytes, or that there would even be a need for such compression. 4k intros, realtime audiovisual presentations created by the demoscene, a community formed in the mid1980s, could be called miniatures of the digital age. In this article I discuss them, on the one hand, as culturalhistorical artifacts that reflect the changes of the technological landscape and the demo culture itself and, on the other hand, as creative works of art that have let their authors exhibit their wizardry to others. In addition to a historical overview, I will focus on various tools and approaches that have been used to tackle the challenge of four kilobytes. Most of the discussion will revolve around intros created for IBM PC compatible computers due to WiderScreen 1–2/2014: Skenet – Scenes their popularity, and because they illustrate the development of computing power and the graphical capabilities of mainstream computers starting from the early 1990s in the best way. -

Times of Change in the Demoscene: a Creative Commu- Nity and Its Relationship with Technology

TIMES OF CHANGE IN THE DEMOSCENE A Creative Community and Its Relationship with Technology Markku Reunanen TURUN YLIOPISTON JULKAISUJA – ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS TURKUENSIS Sarja - ser. B osa - tom. 428 | Humanoria | Turku 2017 University of Turku Faculty of Humanities School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Degree Programme in Cultural Production and Landscape Studies Digital Culture, Juno Doctoral Programme Supervisors Professor Jaakko Suominen University lecturer Petri Saarikoski University of Turku University of Turku Finland Finland Pre-examiners Professor Nick Montfort Associate professor Olli Sotamaa Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of Tampere United States Finland Opponent Assistant professor Carl Therrien University of Montreal Canada The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. ISBN 978-951-29-6716-2 (PRINT) ISBN 978-951-29-6717-9 (PDF) ISSN 0082-6987 (PRINT) ISSN 2343-3191 (ONLINE) Cover image: Markku Reunanen Juvenes Print, Turku, Finland 2017 Abstract UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Faculty of Humanities School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Degree Programme in Cultural Production and Landscape Studies Digital Culture REUNANEN, MARKKU: Times of Change in the Demoscene: A Creative Commu- nity and Its Relationship with Technology Doctoral dissertation, 100 pages, 88 appendix pages January 17, 2017 The demoscene is a form of digital culture that emerged in the mid-1980s after home computers started becoming commonplace. Throughout its approximately thirty years of existence it has changed in a number of ways, due to both external and internal fac- tors. The most evident external driver has been the considerable technological devel- opment of the period, which has forced the community to react in its own particular ways.