The Exodus, Then and Now

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Validity of Human Language: a Vehicle for Divine Truth

Grace Theological Journal 9.1 (1988) 21-43 [Copyright © 1988 Grace Theological Seminary; cited with permission; digitally prepared for use at Gordon and Grace Colleges and elsewhere] THE VALIDITY OF HUMAN LANGUAGE: A VEHICLE FOR DIVINE TRUTH JACK BARENTSEN Doubts have arisen about the adequacy of human language to convey inerrant truth from God to man. These doubts are rooted in an empirical epistemology, as elaborated by Hume, Kant, Heidegger and others. Many theologians adopted such an empirical view and found themselves unable to defend a biblical view of divine, inerrant revelation. Barth was slightly more successful, but in the end he failed. The problem is the empirical epistemology that first analyzes man's relationship with creation. Biblically, the starting point should be an analysis of man's relationship with his Creator. When ap- proached this way, creation (especially the creation of man in God's image) and the incarnation show that God and man possess an adequate, shared communication system that enables God to com- municate intelligibly and inerrantly with man. Furthermore, the Bible's insistence on written revelation shows that inerrant divine communication carries the same authority whether written or spoken. * * * As a result of the materialistic, empirical scepticism of the last two centuries, many theologians entertain doubts about the ade- quacy of human language to convey divine truth (or, in some cases, to convey truth of any kind). This review of the philosophical and theological origins of the current doubts about language lays a foundation for a biblical view of language. THE CONTEMPORARY PROBLEM One recent writer stated the problem of the adequacy of religious language in these words: The problem of religious knowledge, in the context of contemporary philosophical analysis, is basically this: no one has any. -

Illinois Rules of the Road 2021 DSD a 112.35 ROR.Qxp Layout 1 5/5/21 9:45 AM Page 1

DSD A 112.32 Cover 2021.qxp_Layout 1 1/6/21 10:58 AM Page 1 DSD A 112.32 Cover 2021.qxp_Layout 1 5/11/21 2:06 PM Page 3 Illinois continues to be a national leader in traffic safety. Over the last decade, traffic fatalities in our state have declined significantly. This is due in large part to innovative efforts to combat drunk and distracted driving, as well as stronger guidelines for new teen drivers. The driving public’s increased awareness and avoidance of hazardous driving behaviors are critical for Illinois to see a further decline in traffic fatalities. Beginning May 3, 2023, the federal government will require your driver’s license or ID card (DL/ID) to be REAL ID compliant for use as identification to board domestic flights. Not every person needs a REAL ID card, which is why we offer you a choice. You decide if you need a REAL ID or standard DL/ID. More information is available on the following pages. The application process for a REAL ID-compliant DL/ID requires enhanced security measures that meet mandated federal guidelines. As a result, you must provide documentation confirming your identity, Social Security number, residency and signature. Please note there is no immediate need to apply for a REAL ID- compliant DL/ID. Current Illinois DL/IDs will be accepted to board domestic flights until May 3, 2023. For more information about the REAL ID program, visit REALID.ilsos.gov or call 833-503-4074. As Secretary of State, I will continue to maintain the highest standards when it comes to traffic safety and public service in Illinois. -

LOST the Official Show Auction

LOST | The Auction 156 1-310-859-7701 Profiles in History | August 21 & 22, 2010 572. JACK’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO 574. JACK’S COSTUME FROM PLACE LIKE HOME, PARTS 2 THE EPISODE, “EGGTOWN.” & 3.” Jack’s distressed beige Jack’s black leather jack- linen shirt and brown pants et, gray check-pattern worn in the episode, “There’s long-sleeve shirt and blue No Place Like Home, Parts 2 jeans worn in the episode, & 3.” Seen on the raft when “Eggtown.” $200 – $300 the Oceanic Six are rescued. $200 – $300 573. JACK’S SUIT FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO PLACE 575. JACK’S SEASON FOUR LIKE HOME, PART 1.” Jack’s COSTUME. Jack’s gray pants, black suit (jacket and pants), striped blue button down shirt white dress shirt and black and gray sport jacket worn in tie from the episode, “There’s Season Four. $200 – $300 No Place Like Home, Part 1.” $200 – $300 157 www.liveauctioneers.com LOST | The Auction 578. KATE’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE HOME, PART 1.” Kate’s jeans and green but- ton down shirt worn at the press conference in the episode, “There’s No Place Like Home, Part 1.” $200 – $300 576. JACK’S SEASON FOUR DOCTOR’S COSTUME. Jack’s white lab coat embroidered “J. Shephard M.D.,” Yves St. Laurent suit (jacket and pants), white striped shirt, gray tie, black shoes and belt. Includes medical stetho- scope and pair of knee reflex hammers used by Jack Shephard throughout the series. -

Aboard the Exodus: Setting Sail for Freedom’S Shore” (PAGES 14–17) LESSON PLAN by ANN R

“Aboard the Exodus: Setting Sail for Freedom’s Shore” (PAGES 14–17) LESSON PLAN BY ANN R. BERMAN After reading the feature article about the Exodus 1947, students will discuss Watch a newsreel aboutat the many people who took great risks to create a Jewish homeland in Israel. the Exodus 1947 . Through a comparison of the Exodus from Egypt and the Exodus 1947, students www.babaganewz.com will understand the connection between freedom and the Land of Israel. CONCEPTS AND OBJECTIVES would be allowed to enter the land without Arab approval. k Students will understand that creating the modern State Displaced Persons (DP’s): These were people who had been of Israel required risk-taking, hard work, and the efforts forced to leave their homes during WWII. This group of Jews from many parts of the world. The ultimate included the Jewish survivors of the concentration camps success of the Exodus 1947 mission was due to the efforts and Jews who had been in hiding during the war. While of various groups of people, rather than specific non-Jewish DP’s waited in camps until they could return individual “heroes.” Groups of everyday people working to their pre-war homes, Jewish DP’s could not and did not together for a common goal have the power to affect the wish to return. After surviving the concentration camps, course of history. these DP’s lived in DP camps in Germany, Austria, and k For Jews, there is a concrete connection between Italy for many years until a new home could be found for freedom and the Land of Israel. -

Melchizedek Or the Secret Doctrine of the Bible by JC Grumbine

Melchizedek or the Secret Doctrine of the Bible by J.C. Grumbine Melchizedek or the Secret Doctrine of the Bible by J.C. Grumbine Published in 1919 "I will utter things which have been kept secret from the foundation of the world". Matthew 13: 35 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Lecture 1 Who is Melchizedek? Biblical History. His Office and His Order The Secret Doctrines of the Order. Its Myths, Mysteries, Lecture 2 Symbolisms, Canons, Philosophy The Secret Doctrine on Four Planes of Expression and Lecture 3 Manifestation Lecture 4 The Christ Psychology and Christian Mysticism Lecture 5 The Key - How Applied. Divine Realization and Illumination Page 1 Melchizedek or the Secret Doctrine of the Bible by J.C. Grumbine INTRODUCTION The Bible has been regarded as a sealed book, its mysteries impenetrable, its knowledge unfathomable, its key lost. Even its miracles have been so excluded from scientific research as to be invested with a supernaturalism which forever separated them from the possibility of human understanding and rational interpretation. In the midst of these revolutionary times, it is not strange that theology and institutional Christianity should feel the foundations of their authority slipping from them, and a new, broader and more spiritual thought of man and God taking their places. All this is a part of the general awakening of mankind and has not come about in a day or a year. It grew. It is still growing, because the soul is eternal and justifies and vindicates its own unfoldment. Some see in this new birth of man that annihilation of church and state, but others who are more informed and illumined, realized that the chaff and dross of error are being separated from the wheat and gold of truth and that only the best, and that which is for the highest good of mankind will remain. -

Trademark / Service Mark Database Subscription Form

South Dakota Secretary of State Trademark/Service Mark Database Terms and Conditions South Dakota Secretary of State’s (SOS) office provides a download of all Trademark/Service mark Registration records. The download is made available in 3 ways: a Full Database download (Updated Quarterly), a download of all Quarterly Updates, and a download of all images done Quarterly. Subscribers wishing to use the service made available by the South Dakota Secretary of State will need to complete this form. Trademark/Service mark Registration Database downloads are available in Excel (.xlsx) format and will be emailed to the subscriber. The Subscriber and The Office of Secretary of State (SOS) agree to contract for the Trademark/Service mark Registration database provided by the SOS as per the Terms and Conditions stated below. 1. This agreement sets forth the terms and conditions under which SOS will provide services to the subscriber. 2. Term: SOS reserves the right to withdraw any service without consulting Subscriber prior to withdrawing such service and shall have no liability whatsoever to Subscriber in connection with deletion of any service. Subscriber may terminate this agreement at any time by written notice to the SOS. 3. Subscriber acknowledges that he/she has read the Agreement and agrees that it is the complete and exclusive statement between the parties, superseding all other communications, oral or written. This agreement and other notices provided to the Subscriber by SOS constitute the entire agreement between the parties. This agreement may be modified only by written amendment signed by the parties except as otherwise provided in this paragraph. -

Time Travel and Free Will in the Television Show Lost

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Praxes of popular culture No. 1 - Year 9 12/2018 - LC.1 Kevin Drzakowski, University of Wisconsin-Stout, USA Paradox Lost: Time Travel and Free Will in the Television Show Lost Abstract The television series Lost uses the motif of time travel to consider the problem of human free will, following the tradition of Humean compatibilism in asserting that human beings possess free will in a deterministic universe. This paper reexamines Lost’s final mystery, the “Flash Sideways” world, presenting a revisionist view of the show’s conclusion that figures the Flash Sideways as an outcome of time travel. By considering the perspectives of observers who exist both within time and outside of it, the paper argues that the characters of Lost changed their destinies, even though the rules of time travel in Lost’s narrative assert that history cannot be changed. Keywords: Lost, time travel, Hume, free will, compatibilism My purpose in this paper is twofold. First, I intend to argue that ABC’s Lost follows a tradition of science fiction in using time travel to consider the problem of human free will, making an original contribution to the debate by invoking a narrative structure previously unseen in time travel stories. I hope to show that Lost, a television show that became increasingly invested in questions over free will and fate as the series progressed, makes a case for free will in the tradition of Humean compatibilism, asserting that human beings possess free will even in a deterministic world. -

A Constructive Theology of Truth As a Divine Name with Reference to the Bible and Augustine

A Constructive Theology of Truth as a Divine Name with reference to the Bible and Augustine by Emily Sumner Kempson Murray Edwards College September 2019 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright © 2020 Emily Sumner Kempson 2 Preface This thesis is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the relevant Degree Committee. 3 4 A Constructive Theology of Truth as a Divine Name with Reference to the Bible and Augustine (Summary) Emily Sumner Kempson This study is a work of constructive theology that retrieves the ancient Christian understanding of God as truth for contemporary theological discourse and points to its relevance to biblical studies and philosophy of religion. The contribution is threefold: first, the thesis introduces a novel method for constructive theology, consisting of developing conceptual parameters from source material which are then combined into a theological proposal. -

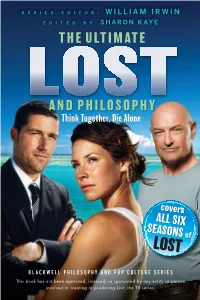

The Ultimate and Philosophy

PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE IRWIN SERIES EDITOR: WILLIAM IRWIN What are the metaphysics of time travel? EDITED BY SHARON KAYE How can Hurley exist in two places at the same time? THE ULTIMATE What does it mean for something to be possibly true in the fl ash-sideways universe? Does Jack have a moral obligation to his father? THE ULTIMATE What is the Tao of John Locke? Dude. So there’s, like, this island? And a bunch of us were on Oceanic fl ight 815 and we crashed on it. I kinda thought it was my fault, because of those numbers. I thought they were bad luck. We’ve seen the craziest things here, like a polar bear and a Smoke Monster, and we traveled through time back to the 1970s. And we met the Dharma dudes. Arzt even blew himself up. For a long time, I thought I was crazy. But now, I think it might have been destiny. The island’s made me question a lot of things. Like, why is it that Locke and Desmond have the same names as real philosophers? Why do so many of us have AND PHILOSOPHY trouble with our dads? Did Jack have a choice in becoming our leader? And what’s up Think Together, Die Alone with Vincent? I mean, he’s gotta be more than just a dog, right? I dunno. We’ve all felt pretty lost. I just hope we can trust Jacob, otherwise . whoa. With its sixth-season series fi nale, Lost did more than end its run as one of the most AND PHILOSOPHY talked-about TV programs of all time; it left in its wake a complex labyrinth of philosophical questions and issues to be explored. -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

Iraqi Jews: a History of Mass Exodus by Abbas Shiblak, Saqi, 2005, 215 Pp

Iraqi Jews: A History of Mass Exodus by Abbas Shiblak, Saqi, 2005, 215 pp. Rayyan Al-Shawaf The 2003 toppling of Saddam Hussein’s Baath regime and the occupation of Iraq by Allied Coalition Forces has served to generate a good deal of interest in Iraqi history. As a result, in 2005 Saqi reissued Abbas Shiblak’s 1986 study The Lure of Zion: The Case of the Iraqi Jews. The revised edition, which includes a preface by Iraq historian Peter Sluglett as well as minor additions and modifications by the author, is entitled The Iraqi Jews: A History of Mass Exodus. Shiblak’s book, which deals with the mass immigration of Iraqi Jews to Israel in 1950-51, is important both as one of the few academic studies of the subject as well as a reminder of a time when Jews were an integral part of Iraq and other Arab countries. The other significant study of this subject is Moshe Gat’s The Jewish Exodus from Iraq, 1948-1951, which was published in 1997. A shorter encapsulation of Gat’s argument can be found in his 2000 Israel Affairs article Between‘ Terror and Emigration: The Case of Iraqi Jewry.’ Because of the diametrically opposed conclusions arrived at by the authors, it is useful to compare and contrast their accounts. In fact, Gat explicitly refuted many of Shiblak’s assertions as early as 1987, in his Immigrants and Minorities review of Shiblak’s The Lure of Zion. It is unclear why Shiblak has very conspicuously chosen to ignore Gat’s criticisms and his pointing out of errors in the initial version of the book. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France.