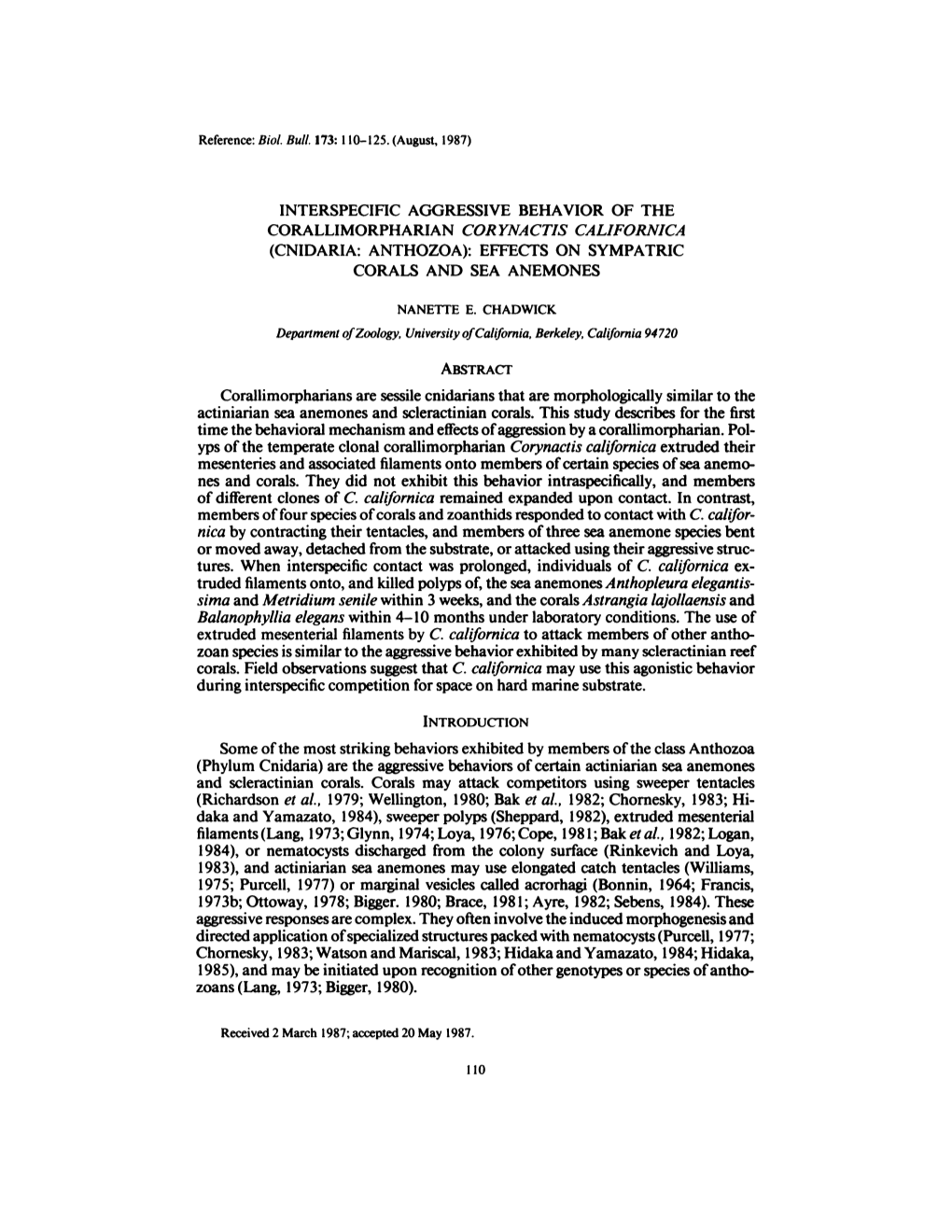

Cnidaria: Anthozoa): Effects on Sympatric Corals and Sea Anemones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARINE FAUNA and FLORA of BERMUDA a Systematic Guide to the Identification of Marine Organisms

MARINE FAUNA AND FLORA OF BERMUDA A Systematic Guide to the Identification of Marine Organisms Edited by WOLFGANG STERRER Bermuda Biological Station St. George's, Bermuda in cooperation with Christiane Schoepfer-Sterrer and 63 text contributors A Wiley-Interscience Publication JOHN WILEY & SONS New York Chichester Brisbane Toronto Singapore ANTHOZOA 159 sucker) on the exumbrella. Color vari many Actiniaria and Ceriantharia can able, mostly greenish gray-blue, the move if exposed to unfavorable condi greenish color due to zooxanthellae tions. Actiniaria can creep along on their embedded in the mesoglea. Polyp pedal discs at 8-10 cm/hr, pull themselves slender; strobilation of the monodisc by their tentacles, move by peristalsis type. Medusae are found, upside through loose sediment, float in currents, down and usually in large congrega and even swim by coordinated tentacular tions, on the muddy bottoms of in motion. shore bays and ponds. Both subclasses are represented in Ber W. STERRER muda. Because the orders are so diverse morphologically, they are often discussed separately. In some classifications the an Class Anthozoa (Corals, anemones) thozoan orders are grouped into 3 (not the 2 considered here) subclasses, splitting off CHARACTERISTICS: Exclusively polypoid, sol the Ceriantharia and Antipatharia into a itary or colonial eNIDARIA. Oral end ex separate subclass, the Ceriantipatharia. panded into oral disc which bears the mouth and Corallimorpharia are sometimes consid one or more rings of hollow tentacles. ered a suborder of Scleractinia. Approxi Stomodeum well developed, often with 1 or 2 mately 6,500 species of Anthozoa are siphonoglyphs. Gastrovascular cavity compart known. Of 93 species reported from Ber mentalized by radially arranged mesenteries. -

End-Permian Mass Extinction in the Oceans: an Ancient Analog for the Twenty-First Century?

EA40CH05-Payne ARI 23 March 2012 10:24 End-Permian Mass Extinction in the Oceans: An Ancient Analog for the Twenty-First Century? Jonathan L. Payne1 and Matthew E. Clapham2 1Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305; email: [email protected] 2Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz, California 95064; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2012. 40:89–111 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on ocean acidification, evolution, isotope geochemistry, volcanism, January 3, 2012 biodiversity The Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences is online at earth.annualreviews.org Abstract This article’s doi: The greatest loss of biodiversity in the history of animal life occurred at the 10.1146/annurev-earth-042711-105329 end of the Permian Period (∼252 million years ago). This biotic catastro- Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2012.40:89-111. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org Copyright c 2012 by Annual Reviews. phe coincided with an interval of widespread ocean anoxia and the eruption All rights reserved of one of Earth’s largest continental flood basalt provinces, the Siberian by Stanford University - Main Campus Robert Crown Law Library on 06/04/12. For personal use only. 0084-6597/12/0530-0089$20.00 Traps. Volatile release from basaltic magma and sedimentary strata dur- ing emplacement of the Siberian Traps can account for most end-Permian paleontological and geochemical observations. Climate change and, per- haps, destruction of the ozone layer can explain extinctions on land, whereas changes in ocean oxygen levels, CO2, pH, and temperature can account for extinction selectivity across marine animals. -

Patterns of Septal Biomineralization in Scleractinia Compared with Their 28S Rrna Phylogeny

PBlackwell Publishingatterns Ltd. of septal biomineralization in Scleractinia compared with their 28S rRNA phylogeny: a dual approach for a new taxonomic framework JEAN-PIERRE CUIF, GUILLAUME LECOINTRE, CHRISTINE PERRIN, ANNIE TILLIER & SIMON TILLIER Accepted: 2 December 2002 Cuif, J.-P., Lecointre, G., Perrin, C., Tillier, A. & Tillier, S. (2003). Patterns of septal bio- mineralization in Scleractinia compared with their 28S rRNA phylogeny: a dual approach for a new taxonomic framework. — Zoologica Scripta, 32, 459–473. A molecular phylogeny of the Scleractinia is reconstructed from approximately 700 nucleo- tides of the 5′end of the 28S rDNA obtained from 40 species. A comparison of molecular phylogenic trees with biomineralization patterns of coral septa suggests that at least five clades are corroborated by both types of data. Agaricidae and Dendrophylliidae are found to be monophyletic, that is supported by microstructural data. Conversely, Faviidae and Caryophyl- liidae are found to be paraphyletic: Cladocora should be excluded from the faviids, whereas Eusmilia should be excluded from the caryophylliids. The conclusion is also supported by the positions, sizes and shapes of centres of calcification. The traditional Guyniidae are diphyletic, corroborating Stolarski’s hypothesis ‘A’. Some results from our most parsimonious trees are not strongly statistically supported but corroborated by other molecular studies and micro- structural observations. For example, in the scleractinian phylogenetic tree, there are several lines of evidence (including those from our data) to distinguish a Faviidae–Mussidae lineage and a Dendrophylliidae–Agaricidae–Poritidae–Siderastreidae lineage. From a methodological standpoint, our results suggest that co-ordinated studies creating links between biomineralization patterns and molecular phylogeny may provide an efficient working approach for a re- examination of scleractinian classification. -

Abundance and Clonal Replication in the Tropical Corallimorpharian Rhodactis Rhodostoma

Invertebrate Biology 119(4): 351-360. 0 2000 American Microscopical Society, Inc. Abundance and clonal replication in the tropical corallimorpharian Rhodactis rhodostoma Nanette E. Chadwick-Furmana and Michael Spiegel Interuniversity Institute for Marine Science, PO. Box 469, Eilat, Israel, and Faculty of Life Sciences, Bar Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel Abstract. The corallimorpharian Rhodactis rhodostoma appears to be an opportunistic species capable of rapidly monopolizing patches of unoccupied shallow substrate on tropical reefs. On a fringing coral reef at Eilat, Israel, northern Red Sea, we examined patterns of abundance and clonal replication in R. rhodostoma in order to understand the modes and rates of spread of polyps across the reef flat. Polyps were abundant on the inner reef flat (maximum 1510 polyps m-* and 69% cover), rare on the outer reef flat, and completely absent on the outer reef slope at >3 m depth. Individuals cloned throughout the year via 3 distinct modes: longitudinal fission, inverse budding, and marginal budding. Marginal budding is a replicative mode not previously described. Cloning mode varied significantly with polyp size. Approximately 9% of polyps cloned each month, leading to a clonal doubling time of about 1 year. The rate of cloning varied seasonally and depended on day length and seawater temperature, except for a brief reduction in cloning during midsummer when polyps spawned gametes. Polyps of R. rhodo- stoma appear to have replicated extensively following a catastrophic low-tide disturbance in 1970, and have become an alternate dominant to stony corals on parts of the reef flat. Additional key words: Cnidaria, coral reef, sea anemone, asexual reproduction, Red Sea Soft-bodied benthic cnidarians such as sea anemo- & Chadwick-Furman 1999a). -

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico: Depth and Geographical Distribution

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico: Depth and Geographical Distribution by Peter J. Etnoyer1 and Stephen D. Cairns2 1. NOAA Center for Coastal Monitoring and Assessment, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Charleston, SC 2. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC This annex to the U.S. Gulf of Mexico chapter in “The State of Deep‐Sea Coral Ecosystems of the United States” provides a list of deep‐sea coral taxa in the Phylum Cnidaria, Classes Anthozoa and Hydrozoa, known to occur in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 1). Deep‐sea corals are defined as azooxanthellate, heterotrophic coral species occurring in waters 50 m deep or more. Details are provided on the vertical and geographic extent of each species (Table 1). This list is adapted from species lists presented in ʺBiodiversity of the Gulf of Mexicoʺ (Felder & Camp 2009), which inventoried species found throughout the entire Gulf of Mexico including areas outside U.S. waters. Taxonomic names are generally those currently accepted in the World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS), and are arranged by order, and alphabetically within order by suborder (if applicable), family, genus, and species. Data sources (references) listed are those principally used to establish geographic and depth distribution. Only those species found within the U.S. Gulf of Mexico Exclusive Economic Zone are presented here. Information from recent studies that have expanded the known range of species into the U.S. Gulf of Mexico have been included. The total number of species of deep‐sea corals documented for the U.S. -

Volume 2. Animals

AC20 Doc. 8.5 Annex (English only/Seulement en anglais/Únicamente en inglés) REVIEW OF SIGNIFICANT TRADE ANALYSIS OF TRADE TRENDS WITH NOTES ON THE CONSERVATION STATUS OF SELECTED SPECIES Volume 2. Animals Prepared for the CITES Animals Committee, CITES Secretariat by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre JANUARY 2004 AC20 Doc. 8.5 – p. 3 Prepared and produced by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, Cambridge, UK UNEP WORLD CONSERVATION MONITORING CENTRE (UNEP-WCMC) www.unep-wcmc.org The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre is the biodiversity assessment and policy implementation arm of the United Nations Environment Programme, the world’s foremost intergovernmental environmental organisation. UNEP-WCMC aims to help decision-makers recognise the value of biodiversity to people everywhere, and to apply this knowledge to all that they do. The Centre’s challenge is to transform complex data into policy-relevant information, to build tools and systems for analysis and integration, and to support the needs of nations and the international community as they engage in joint programmes of action. UNEP-WCMC provides objective, scientifically rigorous products and services that include ecosystem assessments, support for implementation of environmental agreements, regional and global biodiversity information, research on threats and impacts, and development of future scenarios for the living world. Prepared for: The CITES Secretariat, Geneva A contribution to UNEP - The United Nations Environment Programme Printed by: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge CB3 0DL, UK © Copyright: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre/CITES Secretariat The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of UNEP or contributory organisations. -

Adaptive Divergence, Neutral Panmixia, and Algal Symbiont Population Structure in the Temperate Coral Astrangia Poculata Along the Mid-Atlantic United States

Adaptive divergence, neutral panmixia, and algal symbiont population structure in the temperate coral Astrangia poculata along the Mid-Atlantic United States Hannah E. Aichelman1,2 and Daniel J. Barshis2 1 Department of Biology, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA ABSTRACT Astrangia poculata is a temperate scleractinian coral that exists in facultative symbiosis with the dinoflagellate alga Breviolum psygmophilum across a range spanning the Gulf of Mexico to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Our previous work on metabolic thermal performance of Virginia (VA) and Rhode Island (RI) populations of A. poculata revealed physiological signatures of cold (RI) and warm (VA) adaptation of these populations to their respective local thermal environments. Here, we used whole-transcriptome sequencing (mRNA-Seq) to evaluate genetic differences and identify potential loci involved in the adaptive signature of VA and RI populations. Sequencing data from 40 A. poculata individuals, including 10 colonies from each population and symbiotic state (VA-white, VA-brown, RI-white, and RI-brown), yielded a total of 1,808 host-associated and 59 algal symbiont-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) post filtration. Fst outlier analysis identified 66 putative high outlier SNPs in the coral host and 4 in the algal symbiont. Differentiation of VA and RI populations in the coral host was driven by putatively adaptive loci, not neutral divergence (Fst = 0.16, p = 0.001 and Fst = 0.002, p = 0.269 for outlier and neutral SNPs respectively). In contrast, we found evidence of neutral population differentiation in B. psygmophilum (Fst = 0.093, p = 0.001). -

(Anthozoa) from the Lower Oligocene (Rupelian) of the Eastern Alps, Austria

TO L O N O G E I L C A A P I ' T A A T L E I I A Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana, 59 (3), 2020, 319-336. Modena C N O A S S. P. I. Scleractinian corals (Anthozoa) from the lower Oligocene (Rupelian) of the Eastern Alps, Austria Rosemarie Christine Baron-Szabo* & Diethard Sanders R.C. Baron-Szabo, Department of Invertebrate Zoology, Smithsonian Institution, NMNH, W-205, MRC 163, P.O. Box 37012, Washington DC, 20013- 7012 USA; Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Senckenberganlage 25, D-60325 Frankfurt/Main, Germany; [email protected]; Rosemarie.Baron- [email protected] *corresponding author D. Sanders, Institut für Geologie, Universität of Innsbruck, Innrain 52, A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] KEY WORDS - Scleractinia, taxonomy, paleoecology, paleobiogeography. ABSTRACT - In the Werlberg Member (Rupelian pro parte) of the Paisslberg Formation (Eastern Alps), an assemblage of colonial corals of eleven species pertaining to eleven genera and eleven families was identified:Stylocoenia carryensis, Acropora lavandulina, ?Colpophyllia sp., Dendrogyra intermedia, Caulastraea pseudoflabellum, Hydnophyllia costata, Pindosmilia cf. brunni, Actinacis rollei, Pavona profunda, Agathiphyllia gregaria, and Faksephyllia faxoensis. This is the first Oligocene coral assemblage reported from the Paisslberg Formation (Werlberg Member) of the Eastern Alps, consisting exclusively of colonial forms. The assemblage represents the northernmost fauna of reefal corals reported to date for Rupelian time. The Werlberg Member accumulated during marine transgression onto a truncated succession of older carbonate rocks. The corals grew as isolated colonies and in carpets in a protected shoreface setting punctuated by high-energy events. Coral growth forms comprise massive to sublamellar forms, and branched (dendroid, ramose) forms. -

Factors Affecting the Abundance of Paracyathus Stearns!! on Subtidal Rock Walls

MLML / M8~RllIBR;jRY 8272 MOSS LANDING RD. MOSS LANDING, CA 95039 FACTORS AFFECTING THE ABUNDANCE OF PARACYATHUS STEARNS!! ON SUBTIDAL ROCK WALLS by Mark Pranger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofScience in Marine Science in the School ofNatural Sciences California State University, Fresno August 1999 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my graduate advisory committee for their advice and guidance during this process. Dr. James Nybakken for his interest and education in invertebrate biology and for allowing me to help in the teaching of others. For the insights and humor of Dr. Mike Foster, that helped improve this study and my education. For the help of Dr. Stephen Ervin who in the last hours help me through all CSU Fresno's paper work and deadlines. I am grateful to the staff at the Pollution Studies Lab at Granite Canyon for their help during experiments and for allowing me the use of their working space. I am indebted to the staff at Moss Landing Marine Labs that kept all the equipment working and operational, and to the Dr. Earl and Ethel Myers Oceanographic and Marine Biology Trust for helping to fund this project. Most of all, thanks goes to the many students at Moss Landing. Without their help this study would not have been completed. Special thanks goes to; Mat Edwards for being a faithful dive buddy, to Torno Eguchi, Michelle White, Bryn Phillips, Cassandra Roberts, Michelle Lander, and Lara Lovera for their help on statistics and editing of early drafts, and especially to Michele Jacobi for her help in all aspects of this study and her constant encouragement for me to finish. -

The Diet and Predator-Prey Relationships of the Sea Star Pycnopodia Helianthoides (Brandt) from a Central California Kelp Forest

THE DIET AND PREDATOR-PREY RELATIONSHIPS OF THE SEA STAR PYCNOPODIA HELIANTHOIDES (BRANDT) FROM A CENTRAL CALIFORNIA KELP FOREST A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Moss Landing Marine Laboratories San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Timothy John Herrlinger December 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments iv Abstract vi List of Tables viii List of Figures ix INTRODUCTION 1 MATERIALS AND METHODS Site Description 4 Diet 5 Prey Densities and Defensive Responses 8 Prey-Size Selection 9 Prey Handling Times 9 Prey Adhesion 9 Tethering of Calliostoma ligatum 10 Microhabitat Distribution of Prey 12 OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS Diet 14 Prey Densities 16 Prey Defensive Responses 17 Prey-Size Selection 18 Prey Handling Times 18 Prey Adhesion 19 Tethering of Calliostoma ligatum 19 Microhabitat Distribution of Prey 20 DISCUSSION Diet 21 Prey Densities 24 Prey Defensive Responses 25 Prey-Size Selection 27 Prey Handling Times 27 Prey Adhesion 28 Tethering of Calliostoma ligatum and Prey Refugia 29 Microhabitat Distribution of Prey 32 Chemoreception vs. a Chemotactile Response 36 Foraging Strategy 38 LITERATURE CITED 41 TABLES 48 FIGURES 56 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My span at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories has been a wonderful experience. So many people have contributed in one way or another to the outcome. My diving buddies perse- vered through a lot and I cherish our camaraderie: Todd Anderson, Joel Thompson, Allan Fukuyama, Val Breda, John Heine, Mike Denega, Bruce Welden, Becky Herrlinger, Al Solonsky, Ellen Faurot, Gilbert Van Dykhuizen, Ralph Larson, Guy Hoelzer, Mickey Singer, and Jerry Kashiwada. Kevin Lohman and Richard Reaves spent many hours repairing com puter programs for me. -

Kelp Forest Monitoring Handbook — Volume 1: Sampling Protocol

KELP FOREST MONITORING HANDBOOK VOLUME 1: SAMPLING PROTOCOL CHANNEL ISLANDS NATIONAL PARK KELP FOREST MONITORING HANDBOOK VOLUME 1: SAMPLING PROTOCOL Channel Islands National Park Gary E. Davis David J. Kushner Jennifer M. Mondragon Jeff E. Mondragon Derek Lerma Daniel V. Richards National Park Service Channel Islands National Park 1901 Spinnaker Drive Ventura, California 93001 November 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................1 MONITORING DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS ......................................................... Species Selection ...........................................................................................2 Site Selection .................................................................................................3 Sampling Technique Selection .......................................................................3 SAMPLING METHOD PROTOCOL......................................................................... General Information .......................................................................................8 1 m Quadrats ..................................................................................................9 5 m Quadrats ..................................................................................................11 Band Transects ...............................................................................................13 Random Point Contacts ..................................................................................15 -

The Earliest Diverging Extant Scleractinian Corals Recovered by Mitochondrial Genomes Isabela G

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The earliest diverging extant scleractinian corals recovered by mitochondrial genomes Isabela G. L. Seiblitz1,2*, Kátia C. C. Capel2, Jarosław Stolarski3, Zheng Bin Randolph Quek4, Danwei Huang4,5 & Marcelo V. Kitahara1,2 Evolutionary reconstructions of scleractinian corals have a discrepant proportion of zooxanthellate reef-building species in relation to their azooxanthellate deep-sea counterparts. In particular, the earliest diverging “Basal” lineage remains poorly studied compared to “Robust” and “Complex” corals. The lack of data from corals other than reef-building species impairs a broader understanding of scleractinian evolution. Here, based on complete mitogenomes, the early onset of azooxanthellate corals is explored focusing on one of the most morphologically distinct families, Micrabaciidae. Sequenced on both Illumina and Sanger platforms, mitogenomes of four micrabaciids range from 19,048 to 19,542 bp and have gene content and order similar to the majority of scleractinians. Phylogenies containing all mitochondrial genes confrm the monophyly of Micrabaciidae as a sister group to the rest of Scleractinia. This topology not only corroborates the hypothesis of a solitary and azooxanthellate ancestor for the order, but also agrees with the unique skeletal microstructure previously found in the family. Moreover, the early-diverging position of micrabaciids followed by gardineriids reinforces the previously observed macromorphological similarities between micrabaciids and Corallimorpharia as