ISSUE 003: the LOVE & SEX ISSUE Editor's Note

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

The World-Changer's Manifesto

THE WORLD-CHANGER’S MANIFESTO ROBIN SHARMA ALSO BY ROBIN SHARMA The 5 AM Club The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari The Greatness Guide The Greatness Guide, Book 2 The Leader Who Had No Title Who Will Cry When You Die? Leadership Wisdom from The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari Family Wisdom from The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari Discover Your Destiny with The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari The Secret Letters of The Monk Who Sold His Ferrari The Mastery Manual The Little Black Book for Stunning Success The Saint, the Surfer, and the CEO PRAISE FOR ROBIN SHARMA “Leadership Legend” CNN “Global Humanitarian” FORBES “Rock Star Leadership Guru” The Globe and Mail “Robin Sharma’s books are helping people all over the world lead great lives.” Paulo Coelho “Leadership Guru” The Financial Times (UK) MESSAGE FROM THE AUTHOR + DEDICATION Dear Reader + Possibilitarian: I feel grateful and blessed that you hold this book in your hands. Clearly, something deep within you longs for the fullest expression of your primal genius and the realization of your natural heroism. For over two decades I’ve mentored famed billionaires, industry titans and sports superstars on the mindsets, routines, systems and tactics of world-class performance. In this playbook, I share some of the key elements of my methodology with you. The world is in a volatile place right now. For people operating as victims, the times ahead will be terrifying. Yet, for producers behaving as leaders [and even heroes], the future will not only be inspiring but also bring with it boundless amounts productivity, prosperity and impact. -

BDSM: Safer Kinky

BDSM SAFER KINKY SEX If sexually explicit information about BDSM activities might offend you, then this information is not for you. 1 BDSM Etiquette BDSM etiquette is about respect and communication: RESPECT: Negotiate all the limits and terms (including ‘safe’ words and signals) of a scene before you start to play. A ‘safe’ word (or signal) is used in BDSM play to stop the scene immediately. Some people use green, yellow, and red. These systems are there to protect everyone involved. Respect the limits and feelings of other players (and your own) at all times. COMMUNICATION: Discuss interests, pleasures, perceived needs, physical limitations, past experiences, health needs, and STI status with your partner(s). If you are unsure of a sexual or BDSM activity, then hold off until someone experienced teaches you the safety aspects. Discussion builds intimacy. You and your partner(s) will have more fun! BDSM Risk Reduction Responsible BDSM has always been about practicing safety, so it’s important to understand the risks involved in BDSM play, and how to minimize them. BDSM activities have generally been classed as low risk for HIV transmission. This booklet contains practical guidelines and This means that only a small number of people advice on the prevention of Human Immuno- are likely to have contracted HIV, or passed on deficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis C (HCV), and HIV, while practising BDSM. HIV is not the only other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) sexually transmitted infection (STI), and there are within bondage and discipline, dominance and other possible dangers associated with some submission, and sadomasochism (BDSM) play. -

Volume 9 800-729-6423 | a Catalogue of Erotic Books

a catalogue of erotic books Volume 9 800-729-6423 | WWW.REVELBOOKS.COM a catalogue of erotic books TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW REVEL TITLES . 1-12 REVEL BESTSELLERS . 13-19 PHOTOGRAPHY . 20-21 EROTIC ART & ILLUSTRATION . 22-23 HOW-TO . 24-25 FETISH & BDSM. 26-29 EROTIC COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS . 30-32 EROTIC FICTION. 33-35 SEX HUMOR . 36 EROTIC FILM . 37 GAY. 38 GAY TRAVEL . 39 SENSUAL MASSAGE . 40 Front cover, back cover and interior photographs courtesy of Goliath, publisher of Hot Luxury Girls, Best of Sugar Posh Beauties, by Tammy Sanborn, featured on page 21 of this catalog. Catalog design & layout by Dan Nolte, based on an original design by Rama Crouch-Wong WWW.REVELBOOKS.COM | 800-729-6423 a catalogue of erotic books THE FOLLOWING PUBLISHERS Arcata Arts REPRESENTED BY SCB DISTRIBUTORS Baby Tattoo Books ARE INCLUDED IN THIS CATALOG BDSM Press Chimera Books Circlet Press Daedalus Publishing Damron Guides Down There Press Drago Editions Akileos Erotic Review Press ES Publishing FAB Press Flesk Publications Goliath Books Greenery Press GW Enterprises Last Gasp Lioness for Lovers Mental Gears Publishing MixOfPix Nicotext Pacific Media Priaprism Press Rankin Photography Rock Out Books Skin Two Wet Angel Books Xcite Books NEW REVEL TITLES BUTT BABES Young, Fresh, Sexy, Firm Dave Naz Within these pages, the glorious physical masterpiece is rendered welcoming, irresistible, alluring, mysterious and majestic, to be worshiped and adored. In the hands of photographer Dave Naz, every set of cheeks becomes a work of art in luscious tones of pearl, pink, ivory and bronze – portraits so natural and erotic, each feels real enough to touch. -

Introduction to Wax Play

Introduction to Wax Play July 2020 Krome ONYX Introduction Wax play, a form of temperature play, incorporates melting wax of various types to create slight stinging sensations inducing excitement or arousal. In this introduction we will cover tips and techniques for beginners. In addition, we will discuss materials needed and what should be done before, during and after the play session. Materials The safest wax products to use are made of soy and paraffin or a mixture of the two. Paraffin and soy melt at lower temperatures and are least likely to burn your submissive during play. Specific wax is needed during play and should be chosen in its purest form. Before purchasing, read the ingredients to ensure your wax does not have any additives and perfumes. Avoid wax that is dyed with unnatural ingredients, scented, look metallic and products containing beeswax. Consider the allergies of the submissive, a reaction due to negligence will ruin the experience. Typically the decorative candles you have in your home are not the proper type to use for wax play. When selecting a candle, the easiest to master is the classic stick. The surface area of the wax is wide enough to produce safe slow and steady drips. Not to be confused with tapered candles which have a smaller surface area for the wax to pool. Tapered candles elevate the temperature of wax point of contact to the body and can be unsafe for beginners. Pillars and votives are another great option for pooling and allow for a more concentrated pour. Candles that are enclosed in glass or cups should be avoided by beginners. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Act Like a Lady, Think Like a Man: What Men Really Think About Love

ACT LIKE A Lady, THINK LIKE A MAN Steve Harvey * WHAT MEN REALLY THINK A'BOUT LOVE, RELATIONSHIPS, INTIMACY, AND COMMITMENT I 've made a living for more than twenty years making people laugh about themselves, about each other, about family, and friends, and, most certainly, about love, sex, and relationships. My humor is always rooted in truth and full of wisdom the kind that comes from living, watching, learning, and knowing. I'm told my jokes strike chords with people be cause they can relate to them, especially the ones that explore the dynamics of relationships between men and women. It never ceases to amaze me how much people talk about relationships, think about them, read about them, ask about them even get in them without a clue how to move them forward. For sure, if there's anything I've discovered during my journey here on God's earth, it's this: (a) too many women are clueless about men, (b) men get away with a whole lot of stuff in relationships because women have never understood how men think, and (c) I've got some valuable information to change all of that. I discovered this when my career transitioned to radio with the Steve Harvey Morning Show. Back when my show was based in Los Angeles, I created a segment called Ask Steve, during which women could call in and ask anything they wanted to about relationships. Anything. At the very least, I thought Ask Steve would lead to some good comedy, and at .rst, that's pretty much what it was all about for me getting to the jokes. -

The Factory, 1 Park Hill, London SW4 9NS +44(0)20 7499 7550 Www

The Factory, 1 Park Hill, London SW4 9NS +44(0)20 7499 7550 www.mmla.co.uk The Factory, 1 Park Hill, London SW4 9NS +44(0)20 7499 7550 www.mmla.co.uk LONDON CATALOGUE 2020 LITERARY/BOOK CLUB/UPMARKET WOMEN’S A LITTLE HOPE E.J. JOELLA 5 PEOPLE LIKE US ROSEMARY HENNIGAN 6 THE LAMPLIGHTERS EMMA STONEX 7 THE PUSH ASHLEY AUDRAIN 8 THE ENDS OF THE EARTH ABBIE GREAVES 9 THE LAST LIBRARY FREYA SAMPSON 10 THE SEVEN MESSENGERS OF IVY TREMAYNE CLARE POOLEY 11 SAVING MISSY BETH MORREY 12 ANOTHER LIFE JODIE CHAPMAN 13 CRIME/THRILLER/SUSPENSE STRANGERS C.L. TAYLOR 14 THE BURNING GILRLS C.J. TUDOR 15 THE CAPTIVE DEBORAH O’CONNOR 16 GREENWICH PARK KATHERINE FAULKNER 17 THE RECOVERY OF ROSE GOLD STEPHANIE WROBEL 18 THE WRECKAGE ROBIN MORGAN-BENTLEY 19 SEVEN LIES ELIZABETH KAY 20 THE KILLING CHOICE WILL SHINDLER 21 THE PERFECT MOTHER CAROLINE MITCHELL 22 I WILL MAKE YOU PAY TERESA DRISCOLL 23 DARK CORNERS DARREN O’SULLIVAN 24 LIAR LIAR MEL SHERRATT 25 THE TEAM THE TEAM Madeleine Milburn, Director — [email protected] Giles Milburn, Managing Director & Agent — [email protected] Madeleine Milburn, Milburn, Director Director — &[email protected] Agent —[email protected] Liane-Louise Smith, Rights Director — [email protected] Giles Milburn,Milburn, Managing Managing Director Director & Agent& Agent — [email protected]— [email protected] Hayley Steed, Book to Screen Agent & Literary Agent — [email protected] AliceHayley Sutherland Steed, Book-Hawes, to Screen Rights Agent Manager & Literary -

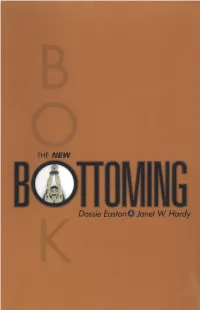

Dossie Easton ; Janet W Hardy the Ne� to © 2003 by Dossie Easton and Janet W

THE NEW Dossie Easton ; Janet W Hardy the ne� To © 2003 by Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in newspaper, magazine, radio, television or Internet reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording or by information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Cover design: DesignTribe Cover illustration: Fish Published in the United States by Greenery Press, 3403 Piedmont Ave. #301, Oakland,CA 94 611,www .greenerypress.com. ISBN 1-8901 59-36-0 Readers should be aware that BDSM, like all sexual activities, carries an inherent risk ofphysical and/oremot ional injury. While we believe that following the guidelines set forth in this book will minimize that potential, the writers and publisher encourage you to be aware that you are taking some risk when you decide to engage in these activities, and to accept personal responsibility forthat risk. In acting on the information in this book, you agree to accept thatinformation as is and with allfau lts. Neither the authors, the publisher, nor anyone else associated with the creation or sale of this book is responsible for any damage sustained. CONTENTS Foreword: Re-Visioning ............................................ i 1. Hello Again! ............ .............................. .. .... ... ....... 1 2. What Is It About Topping, Anyway? ....................... 9 3. What Do Tops Do? ................ ...................... ........ 21 interlude 1 ....... ... .......... ..... ... ... .. .... ........... ... 33 4. Rights and Responsibilities ... ....... ................ .... 37 5. How Do Yo u Learn To Do This Stuff?. .. ............... 49 interlude 2 .. ...... .. ... ......... .. ................ ....... 57 6. Soaring Higher ...................... ................... ... ...... .. 61 7. BDSM Ethics ................... -

12, 2017 Manchester, NH Table of Contents

November 10 - 12, 2017 Manchester, NH Table of Contents Note from the Board 3 General Event Rules 4 Dress Code 6 Nighttime Party Rules 7 Security, Health, & Safety 8 Consent Policy 9 Film Screening 10 Photo Lounge 11 Friday Night Erotic Art Show 12 Presenter Bios 14 Vendors 19 Vendor Bingo 19 Maps 23 Friday Schedule 28 Friday Night Scavenger Hunt 28 Saturday Schedule 30 Sunday Schedule 32 Class Descriptions 34 SIGs and Lounges 51 About Our Sponsor 52 Lunch Options 52 About the Board 54 About the Staff 55 Thank Yous Back Cover Hungry? Boxed lunches may be purchased for Saturday and/or Sunday. Purchases must be made at the Registration Desk by 9:30am the day of. Lunches are $15 each and include: sandwich with lettuce (ham, turkey, or roast beef), chips, fruit, and desert. There is also a vegetarian box option. Looking for more options? See what’s in the area. https://goo.gl/LpWTuV -2- Note from the Board Welcome, and thank you for attending KinkyCon XI! KinkyCon is a grassroots, locally-focused event. Most of our presenters are from our own kinky community. Many of our vendors are folks you know, and they offer their wares at fair prices with exceptional quality, and local service. Our volunteers are from the local community, and give their time to make the Con run as smoothly as possible. They are the reason for the warm, welcoming feel throughout the weekend. We are here to make sure you have a great experience at KinkyCon. If you have any questions, concerns, or problems, please talk to one of the KinkyCon staff members right away. -

BDSM Culture and Submissive-Role Women Lisa R

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2015 Liberation Through Domination: BDSM Culture and Submissive-Role Women Lisa R. Rivoli Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Rivoli, Lisa R., "Liberation Through Domination: BDSM Culture and Submissive-Role Women" (2015). Student Publications. 318. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/318 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 318 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liberation Through Domination: BDSM Culture and Submissive-Role Women Abstract The alternative sexual practices of bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, and sadism and masochism (BDSM) are practiced by people all over the world. In this paper, I will examine the experiences of five submissive-role women in the Netherlands and five in south-central Pennsylvania, focusing specifically on how their involvement with the BDSM community and BDSM culture influences their self-perspective.I will begin my analysis by exploring anthropological perspectives of BDSM and their usefulness in studying sexual counterculture, followed by a consideration of feminist critiques of BDSM and societal barriers faced by women in the community. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan.