“Fooles in Retayle”: Personae and Print in the Long 1590S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hay Any Work for Cooper 1 ______

MARPRELATE TRACTS: HAY ANY WORK FOR COOPER 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ Hay Any Work For Cooper.1 Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication2 to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up3 for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T.C.4 (by which mystical5 letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon,6 or Tom Cook's chaplain)7 hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful8 tub-trimmer.9 Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper's hoops10 to fly off and the bishops' tubs11 to leak out of all cry.12 Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Printed in Europe13 not far from some of the bouncing priests. 1 Cooper: A craftsman who makes and repairs wooden vessels formed of staves and hoops, as casks, buckets, tubs. (OED, p.421) The London street cry ‘Hay any work for cooper’ provided Martin with a pun on Thomas Cooper's surname, which Martin expands on in the next two paragraphs with references to hubs’, ‘barrelling up’, ‘tub-trimmer’, ‘hoops’, ‘leaking tubs’, etc. 2 Hub: The central solid part of a wheel; the nave. (OED, p.993) 3 A commodity commonly ‘barrelled-up’ in Elizabethan England was herring, which probably explains Martin's reference to ‘smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state’. -

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590S Alan

Robert Greene and the Theatrical Vocabulary of the Early 1590s Alan C. Dessen [Writing Robert Greene: Essays on England’s First Notorious Professional Writer, ed. Kirk Melnikoff and Edward Gieskes (Aldershot and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2008), pp. 25-37.\ Here is a familiar tale found in literary handbooks for much of the twentieth century. Once upon a time in the 1560s and 1570s (the boyhoods of Marlowe, Shakespeare, and Jonson) English drama was in a deplorable state characterized by fourteener couplets, allegory, the heavy hand of didacticism, and touring troupes of players with limited numbers and resources. A first breakthrough came with the building of the first permanent playhouses in the London area in 1576- 77 (The Theatre, The Curtain)--hence an opportunity for stable groups to form so as to develop a repertory of plays and an audience. A decade later the University Wits came down to bring their learning and sophistication to the London desert, so that the heavyhandedness and primitive skills of early 1580s playwrights such as Robert Wilson and predecessors such as Thomas Lupton, George Wapull, and William Wager were superseded by the artistry of Marlowe, Kyd, and Greene. The introduction of blank verse and the suppression of allegory and onstage sermons yielded what Willard Thorp billed in 1928 as "the triumph of realism."1 Theatre and drama historians have picked away at some of these details (in particular, 1576 has lost some of its luster or uniqueness), but the narrative of the University Wits' resuscitation of a moribund English drama has retained its status as received truth. -

4. Shakespeare Authorship Doubt in 1593

54 4. Shakespeare Authorship Doubt in 1593 Around the time of Marlowe’s apparent death, the name William Shakespeare appeared in print for the first time, attached to a new work, Venus and Adonis, described by its author as ‘the first heir of my invention’. The poem was registered anonymously on 18 April 1593, and though we do not know exactly when it was published, and it may have been available earlier, the first recorded sale was 12 June. Scholars have long noted significant similarities between this poem and Marlowe’s Hero and Leander; Katherine Duncan-Jones and H.R. Woudhuysen describe ‘compelling links between the two poems’ (Duncan-Jones and Woudhuysen, 2007: 21), though they admit it is difficult to know how Shakespeare would have seen Marlowe’s poem in manuscript, if it was, as is widely believed, being written at Thomas Walsingham’s Scadbury estate in Kent in the same month that Venus was registered in London. The poem is preceded by two lines from Ovid’s Amores, which at the time of publication was available only in Latin. The earliest surviving English translation was Marlowe’s, and it was not published much before 1599. Duncan-Jones and Woudhuysen admit, ‘We don’t know how Shakespeare encountered Amores’ and again speculate that he could have seen Marlowe’s translations in manuscript. Barber, R, (2010), Writing Marlowe As Writing Shakespeare: Exploring Biographical Fictions DPhil Thesis, University of Sussex. Downloaded from www. rosbarber.com/research. 55 Ovid’s poem is addressed Ad Invidos: ‘to those who hate him’. If the title of the epigram poem is relevant, it is more relevant to Marlowe than to Shakespeare: personal attacks on Marlowe in 1593 are legion, and include the allegations in Richard Baines’ ‘Note’ and Thomas Drury’s ‘Remembrances’, Kyd’s letters to Sir John Puckering, and allusions to Marlowe’s works in the Dutch Church Libel. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5tv2w736 Author Harkins, Robert Lee Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. -

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

Grotesque Transformations and the Discourse of Conversion in Robert Greene's Works and Shakespeare's Falstaff

Grotesque Transformations and the Discourse of Conversion in Robert Greene's Works and Shakespeare's Falstaff Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors DiRoberto, Kyle Louise Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 08:47:04 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/203437 GROTESQUE TRANSFORMATIONS AND THE DISCOURSE OF CONVERSION IN ROBERT GREENE'S WORK AND SHAKESPEARE'S FALSTAFF by Kyle DiRoberto _____________________ Copyright © Kyle DiRoberto A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2011 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Kyle DiRoberto entitled Grotesque Transformations and the Discourse of Conversion in Robert Greene's Work and Shakespeare's Falstaff. and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/8/11 Dr. Meg Lota Brown _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/8/11 Dr. Tenney Nathanson _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/8/11 Dr. Carlos Gallego Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Elizabeth I and Irish Rule: Causations For

ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 By KATIE ELIZABETH SKELTON Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2012 ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 Thesis Approved: Dr. Jason Lavery Thesis Adviser Dr. Kristen Burkholder Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 II. ENGLISH RULE OF IRELAND ...................................................... 17 III. ENGLAND’S ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP WITH IRELAND ...................... 35 IV. ENGLISH ETHNIC BIAS AGAINST THE IRISH ................................... 45 V. ENGLISH FOREIGN POLICY & IRELAND ......................................... 63 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................ 94 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Page The Island of Ireland, 1450 ......................................................... 22 Plantations in Ireland, 1550 – 1610................................................ 72 Europe, 1648 ......................................................................... 75 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page -

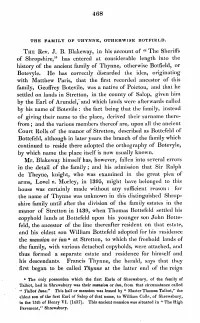

The Sheriffs of Shropshire," Has Entered at Considerable Length Into the History of the Ancient Family of Thynne, Otherwise Botfield, Or Botevyle

468 THE FAMILY OF 'l'HYNNE, OTHERWISE BO'l'FIELD. THE Rev. J. B. Blakeway, in his account of "The Sheriffs of Shropshire," has entered at considerable length into the history of the ancient family of Thynne, otherwise Botfield, or Botevyle. He has correctly discarded the idea, originating with Matthew Paris, that the first recorded ancestor of this family, Geoffrey Botevile, was a native of Poictou, and that he settled on lands in Stretton, in the county of Salop, given him by the Earl of Arundel,' .and which lands were afterwards called by his name of Botevile: the fact being that the family, instead of giving their name to the place, derived their surname there• from; and the various members thereof are, upon all the ancient Court Rolls of the manor of Stretton, described as Bottefeld of Bottefeld, although in later years the branch of the family which continued to reside there adopted the orthography of Botevyle, by which name the place itself is now usually known. Mr. Blakeway himself has, however, fallen into several errors in the detail of the family; and his admission that Sir Ralph de Theyne, knight, who was examined in the great plea of arms, Lovel v. Morley, in 1395, might have belonged to this house was certainly made without any sufficient reason : for the name of Thynne was unknown in this distinguished Shrop• shire family until after the division of the family estates in the manor of Stretton in 1439, when Thomas Bottefeld settled his copyhold lands at Bottefeld upon his younger son John Botte• feld, the ancestor of the line thereafter resident on that estate, and his eldest son William Bottefeld adopted for his residence the mansion or inn a at Stretton, to which the freehold lands of the family, with various detached copyholds, were attached, and thus formed a separate estate and residence for himself and his descendants. -

The Catholic Plots Early Life 1560 1570 1580 1590 1600

Elizabethan England: Part 1 – Elizabeth’s Court and Parliament Family History Who had power in Elizabethan England? Elizabeth’s Court Marriage The Virgin Queen Why did Parliament pressure Elizabeth to marry? Reasons Elizabeth chose Group Responsibilities No. of people: not to marry: Parliament Groups of people in the Royal What did Elizabeth do in response by 1566? Who was Elizabeth’s father and Court: mother? What happened to Peter Wentworth? Council Privy What happened to Elizabeth’s William Cecil mother? Key details: Elizabeth’s Suitors Lieutenants Robert Dudley Francis Duke of Anjou King Philip II of Spain Who was Elizabeth’s brother? Lord (Earl of Leicester) Name: Key details: Key details: Key details: Religion: Francis Walsingham: Key details: Who was Elizabeth’s sister? Justices of Name: Peace Nickname: Religion: Early Life 1560 1570 1580 1590 1600 Childhood 1569 1571 1583 1601 Preparation for life in the Royal The Northern Rebellion The Ridolfi Plot The Throckmorton Plot Essex’s Rebellion Court: Key conspirators: Key conspirators: Key conspirators: Key people: Date of coronation: The plan: The plan: The plan: What happened? Age: Key issues faced by Elizabeth: Key events: Key events: Key events: What did Elizabeth show in her response to Essex? The Catholic Plots Elizabethan England: Part 2 – Life in Elizabethan Times Elizabethan Society God The Elizabethan Theatre The Age of Discovery Key people and groups: New Companies: New Technology: What was the ‘Great Chain of Being’? Key details: Explorers and Privateers Francis Drake John Hawkins Walter Raleigh Peasants Position Income Details Nobility Reasons for opposition to the theatre: Gentry 1577‐1580 1585 1596 1599 Drake Raleigh colonises ‘Virginia’ in Raleigh attacks The Globe Circumnavigation North America. -

Quick Ship Sis

QUICK SHIP FORM 3 working days guaranteed shipping PAGE: 1 OF 4 Model Code Max Qty Qty 1 circuit track 4' - Gray 8004-3C-10 25 _____ 1 circuit track 4' - Black 8004-3C-02 25 _____ 1 circuit track 8' - Gray 8008-3C-10 25 _____ 1 circuit track 8' - Black 8008-3C-02 25 _____ Straight connector - Gray 8020-3C-10 25 _____ Straight connector - Black 8020-3C-02 25 _____ End feeder with 4" Jbox mounting kit 8014-3C-10 25 _____ and square plate - Gray End feeder with 4" Jbox mounting kit 8014-3C-02 25 _____ and square plate - Black Faretto Small, Natural matte anodized 1590S-830-45-120-51 50 _____ 3000K, 80CRI. Faretto Small, Black matte anodized 1590S-830-45-120-52 50 _____ 3000K, 80CRI. Frosted lens 1599 50 _____ Elliptic lens 1598 50 _____ Soft focus lens 1593 50 _____ Hex cell louver - Black 1596-52 50 _____ Cross baffle - Black 1594-52 50 _____ Snoot - Black 1597-52 50 _____ Visor wall washer - Black 1595-52 50 _____ FOR-011 LAST UPDATE: OCTOBER 21, 2016 MH - R1 9320 Boul. St-Laurent, suite 100, Montréal (Québec) Canada H2N 1N7 P.: 514.523.1339 F.: 514.525.6107 www.sistemalux.com QUICK SHIP FORM 3 working days guaranteed shipping PAGE: 2 OF 4 Model Code Max Qty Qty TEK 2 circuit track 8' - Naturel anodized 0167-12 25 _____ TEK 2 circuit track 4' - Black 0166-02 25 _____ TEK 2 circuit track 8' - Naturel anodized 0167-12 25 _____ TEK 2 circuit track 4' - Black 0166-02 25 _____ Live end feed - Gray 0175-10 25 _____ Live end feed - Black 0175-02 25 _____ Linear coupler - Gray 0177-10 25 _____ Linear coupler - Black 0177-02 25 _____ End cap - Gray 0185-10 25 _____ End cap - Black 0185-02 25 _____ Faretto Large, Natural matte anodized 1690-830-45-120-51 50 _____ 3000K, 80CRI. -

Sidney, Shakespeare, and the Elizabethans in Caroline England

Textual Ghosts: Sidney, Shakespeare, and the Elizabethans in Caroline England Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rachel Ellen Clark, M.A. English Graduate Program The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Richard Dutton, Advisor Christopher Highley Alan Farmer Copyright by Rachel Ellen Clark 2011 Abstract This dissertation argues that during the reign of Charles I (1625-42), a powerful and long-lasting nationalist discourse emerged that embodied a conflicted nostalgia and located a primary source of English national identity in the Elizabethan era, rooted in the works of William Shakespeare, Sir Philip Sidney, John Lyly, and Ben Jonson. This Elizabethanism attempted to reconcile increasingly hostile conflicts between Catholics and Protestants, court and country, and elite and commoners. Remarkably, as I show by examining several Caroline texts in which Elizabethan ghosts appear, Caroline authors often resurrect long-dead Elizabethan figures to articulate not only Puritan views but also Arminian and Catholic ones. This tendency to complicate associations between the Elizabethan era and militant Protestantism also appears in Caroline plays by Thomas Heywood, Philip Massinger, and William Sampson that figure Queen Elizabeth as both ideally Protestant and dangerously ambiguous. Furthermore, Caroline Elizabethanism included reprintings and adaptations of Elizabethan literature that reshape the ideological significance of the Elizabethan era. The 1630s quarto editions of Shakespeare’s Elizabethan comedies The Merry Wives of Windsor, The Taming of the Shrew, and Love’s Labour’s Lost represent the Elizabethan era as the source of a native English wit that bridges social divides and negotiates the ii roles of powerful women (a renewed concern as Queen Henrietta Maria became more conspicuous at court). -

ENGLISH NAVAL STRATEGY INTHE 1590S

ENGLISH NAVAL STRATEGY INTHE 1590s SIMÓN ADAMS Profesor de Historia de la Universidad de Strathclyde Until quite recently, the Anglo-Spanish "War" in the period after the Armada of 1588 was one of the least studied subjects of the reign of Elizabeth. For many years, the standard narrative account of the 1590s was that published by the American historian E.P. Cheyney in two volumes in 1914 and 1926 (1). In the past decade, however, this situation has been transformed. Professor Wernham's edition of the List and Analysis ofState Papers Foreign Series (2) has been followed by his detailed study of military operations and diplomacy in the years 1588-1595 (3), and then by his edition of the documents relating to the "Portugal Voyage" of 1589 (4). Within the past two years, Professor MacCaffrey has published the final volume of his trilogy on Elizabeth's reign and Professor Loades his monograph on the Tudor Navy, while Dr. Hammer has completed his dissertation on the most controversial of the political figures of the decade, the 2nd Earl of Essex (5). Much therefore is a good deal clearer than it has been. Yet wider questions remain, particularly over the manner in which Elizabeth's government conducted the war with Spain. In their most recent work both Wernham and MacCaffrey argüe from positions they have established earlier: Wernham for a careful and defensive foreign and military policy, MacCaffrey for an essentially reactive one (6). This is a debate essentially about the queen herself, a particulary difficult The place of publication is understood to be London unless otherwise noted.