Docket 103 Report to Gov. 1983.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Books Discounted All the Time All Prices Subject To

Page 1 of 22 All books discounted all the time All prices subject to change w/o notice September 16, 2021 Alphabetical list by title author list price you pay red = recent 1 One Hundred Years of Enduring Tradition - South Shore Line by Norman Carlson, Stefan Loeb, and Dr. George M. Smerk soft 29.95 25.95 2 100 PCC Trolley Cars Ran in Brooklyn by James C Greller soft 24.95 12.95 3 100 Years of Canadian Railway Recipes by Jean-Paul Viaud, Marie-Paule Partikian for transp Exporail Canada Museum 39.95 34.95 4 100 Years of Steam Locomotives by Walter A. Lucas 72.50 61.95 5 1846 Steamboat Disaster & Railroad Accident Accounts on CD orig publ by Warren Lazell archival, searchable CDROM 25.00 23.95 6 1925 Modern American Locomotive, The: Construction and Operation by Frederick J. Prior softbound 39.50 34.95 7 1st and 2nd Generation Locomotive Handbook, The by J. C. Kissinger soft 4x6 24.95 19.95 8 3 Days - 20 Bucks Rocky Mtn RR Club’s Narrow Gauge Excursions by Stan Rhine soft 24.95 20.95 9 400 Story, The Chicago & North Western's Premier Passenger Trains by Jim Scribbins soft 29.95 24.95 10 567E EMD Engine Maintenance Manual (blower type) by Railway Educational Bureau 8.5x11 comb bound 35.95 30.95 11 722 Miles: The Building of the Subways and How They Transformed New York Centennial Edition by Clifton Hood softbound 23.00 20.95 12 765, A Twenty-First Century Survivor A little history and some great stories from Rich Melvin, the 765's engineer by Richard Melvin 59.95 49.95 13 A Mighty Fine Road A History of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad Company by H. -

Transportation Trips, Excursions, Special Journeys, Outings, Tours, and Milestones In, To, from Or Through New Jersey

TRANSPORTATION TRIPS, EXCURSIONS, SPECIAL JOURNEYS, OUTINGS, TOURS, AND MILESTONES IN, TO, FROM OR THROUGH NEW JERSEY Bill McKelvey, Editor, Updated to Mon., Mar. 8, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is a reference work which we hope will be useful to historians and researchers. For those researchers wanting to do a deeper dive into the history of a particular event or series of events, copious resources are given for most of the fantrips, excursions, special moves, etc. in this compilation. You may find it much easier to search for the RR, event, city, etc. you are interested in than to read the entire document. We also think it will provide interesting, educational, and sometimes entertaining reading. Perhaps it will give ideas to future fantrip or excursion leaders for trips which may still be possible. In any such work like this there is always the question of what to include or exclude or where to draw the line. Our first thought was to limit this work to railfan excursions, but that soon got broadened to include rail specials for the general public and officials, special moves, trolley trips, bus outings, waterway and canal journeys, etc. The focus has been on such trips which operated within NJ; from NJ; into NJ from other states; or, passed through NJ. We have excluded regularly scheduled tourist type rides, automobile journeys, air trips, amusement park rides, etc. NOTE: Since many of the following items were taken from promotional literature we can not guarantee that each and every trip was actually operated. Early on the railways explored and promoted special journeys for the public as a way to improve their bottom line. -

Classic Trains Index 2018-2019

INDEX TO VOLUMES 19 and 20 CLASSIC TRAINS Spring 2018 through Winter 2019 (8 issues) 768 pages HOW TO USE THIS INDEX: Feature material has been indexed three or more times—once by the title under which it was published, again under the author’s last name, and finally under one or more of the subject categories or railroads. Photographs standing alone are indexed (usually by railroad), but photographs within a feature article usually are not separately indexed. Brief items are indexed under the appropriate railroad and/or category. Most references to people are indexed under the company with which they are commonly identified; if there is no common identification, they may be indexed under the person’s last name. Items from countries from other than the U.S. and Canada are indexed under the appropriate country name. ABBREVIATIONS: Sp = Spring issue, Su = Summer issue, Fa = Fall issue, Wi = Winter issue All contents of publications indexed © 2018, and 2019 by Kalmbach Media Co., Waukesha, Wis. A Baldwin Locomotive Works: C Steam’s Last Great Year, Fa19 14 Aberdeen & Rockfish: Baltimore & Ohio: Cajon Standoff, Way It Was, Wi19 80 All-Star Works the Minor Leagues, Archive Treasures, Wi19 46 Amtrak’s Early Years, from the Inside, Fa18 36 California Photo Special (Photo Section), Wi18 44 Abilene & Southern: Cinders: A Forgotten Commodity, Su18 86 California State Railroad Museum, Classics Today, Sp19 103 Steam-powered mixed train at Ballinger, Texas (photo), Su18 50 Dixie Goes the Backway, Sp18 54 California Western: ACF: See American Car & Foundry EM-1 class 2-8-8-4 7609 at night (photo), Fa19 1 Baldwin diesels by enginehouse in 1973 (photo), Su18 56 (color) Action at Jackson (Kentucky), Wi18 50 Engine with Everything (EM-1s), Steam’s Last Great Year, California Zephyr: Adrian & Blissfield: Fa19 22 At Oakland Pier, Sp19 20 (photo) Obscure Ohio & Morenci, Su18 60 George Washington: Seeking Streamliners in 1969, Wi19 54 At Omaha, Overnight to Omaha . -

Donald W. Furler Collection

Donald W. Furler Collection Finding Aid to the Collection at the Center for Railroad Photography & Art Prepared by Adrienne Evans Last updated: 06/19/19 Collection Summary Title: Donald W. Furler Collection Accession Number: 2017.1 Span Dates: 1931-1956 Bulk Dates: 1938-1952 Creator: Furler, Donald Ward, 1917-1994 Extent: 25 archival binders (8.34 linear feet) Language: English Repository: Center for Railroad Photography & Art, Madison, WI Abstract: This collection is composed of photographic images shot by Donald Ward Furler (1917-1994). The bulk of the collection was photographed by Furler, but it also includes work he collected from other rail photographers. Images in the collection primarily depict American railroads, mainly located in New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania. Selected Search Terms Country: Canada United States State: Alabama New York California North Dakota Colorado Ohio Connecticut Ontario (Canada) District of Columbia Pennsylvania Georgia Quebec (Canada) Illinois Saskatchewan (Canada) Iowa Tennessee Kansas Texas Maryland Vermont Massachusetts Virginia Minnesota West Virginia Missouri Montana Montreal (Canada) New Hampshire New Jersey Donald W. Furler Collection 2 Railroad Name: Franklin and Carolina Railroad (Camp A.A. Morrison and Company, Inc. Manufacturing Company) Adirondack Railway Grand Trunk Western Railroad Alton and Southern Railway Company Grand Trunk Railway Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Gifford-Hill and Company Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Harlem Transfer Company Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad -

Nercoupler 272 Jan Mar 2019

Return to the Coastal Newfoundland Railway Page 10 No. 272 JANUARY-MARCH 2019 First Stop: New Jersey– Reviewing the ‘Erie Ltd.’ Then, Syracuse– ‘Empire Junction 2019’ Exploring the NER: Page 14 INSIDE THE COUPLER By JEFF PASTON Open Doehr 2 FROM THE EDITOR . News and Events 3 New York City, specifically. I had one item on my Erie Limited Convention Review 4 bucket list I intended to see since I was so close in Workin’ On the RR 7 Mahwah. Growing up, I loved subways! So, I just had Plans for 2019 Convention 8 to go to the New York Transit Museum in Brooklyn. New Members 9 Once there, I saw the opportunity for an Newfoundland Model Railway 10 ith this issue, we are “Exploring the NER” feature. Check out my visit Visiting NY Transit Museum 14 reaching across the full starting on page 14 of this issue. NER Brass 16 WNMRA Northeastern In some unfinished business, I found more Region to bring you stories that should interest you. information on that Santa Fe jet I’ve placed some “pins” on the NER map “locomotive” shown in COVER PHOTOS above so you can see the scope of The Coupler 270. It was built A steam-powered freight winds Coupler’s “travels.” by Pete Singher for Bill its way through the rural Adiron- We start in Mahwah, New Jersey, Messenger and displayed at the Santa Fe dacks on Jim Heidt’s Ogdens- where Chuck Diljak reviews the successful Modelers Convention in Stamford, CT, in burg & Norwood layout. The HO Erie Limited 2018 NER convention. -

The Phoebe Snow on the Road of Anthracite

1935 - 2015 VOLUME 46 NUMBER 3 DISTRICT 2 - CHAPTER W EBSITE : W W W .NRHS 1. ORG MARCH 2015 The Phoebe Snow on The Road of Anthracite HISTORY AND ROUTE The train was named as part of the DL&W's marketing campaign, around 1900, along with the fictional character of Phoebe Snow to emphasize how the exhaust from its steam locomotives was cleaner than competitors' locomotives, as a result of using anthracite coal. It traveled across New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and the Southern Tier of New York. The line's route pass over the Paulinskill Viaduct and the Delaware River Viaduct of the Lackawanna Cutoff in northeastern New Jersey and the Tunkhannock Viaduct on the portion of its route between Scranton, Pennsylvania to Binghamton, New York. DELAWARE LACKAWANNA & WESTERN ERA (1949-60) On November 15, 1949, the DL&W inaugurated a new streamlined passenger train named after its long-dormant promotional symbol, Pho ebe Snow. Launched by DL&W president William White, the new Phoebe Snow represented the DL&W's modernization of its passenger train fleet, and image, as it became Train No. 3 (westbound) and No. 6 (eastbound), which previously had been assigned the railroad's former premier train, the Lackawanna Limited . The Phoebe Snow ran on a daylight schedule between Hoboken, New Jersey, and Buffalo, New York, making the 396-mile (639-km) trip in about eight hours. Westbound, the sleepers and some coaches would continue on to Chicago, Illinois, over the Nickel Plate Railroad's Nickel Plate Limited and, on return, would be attached in Buffalo to Train No. -

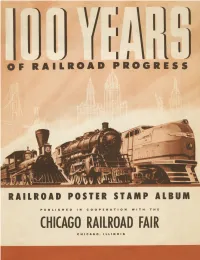

100 Years of Railroad Progress (1948)

OF RAILROAD PROGRESS RAILROAD POSTER STAMP ALBUM PUBLISHED IN COOPERATION WITH THE CHICAGO RAILROAD FAIR CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 100 YEARS OF 111 sa RAILROAD PROGRESS l11111:11:11:13133.112131 FOREWORD When you have assembled in this Railroad Poster Stamp Album the series of Poster Stamps issued in connection with the Chicago Railroad Fair, you will have become better acquainted with the railroads which have joined together in celebrating 100 years of rail- The publication of this Album and the series of Railroad road progress. Never before has the legend of the West and of the Poster Stamps issued in connection with the holding of the men and railroads that followed the Paths of Empire. been depicted Chicago Railroad Fair would not have been possible without in such a unique and interesting manner. the cooperation and contributions of many people in various The Chicago Railroad Fair is presented by the railroads of the offices of the Fair-participating railroads. nation. The occasion it celebrates is the 100th anniversary of the first Pictures used in the stamps and their accompanying stories railroad operation westward from Chicago. It is designed to bring were furnished by the individual railroads, and to them we home to hundreds of thousands of Americans the contributions the are deeply indebted. railroads have made in the development of our country, in the winning of its wars, and in the constant elevation of its standard of living. To the Chicago Railroad Fair Inc., its President Lenox R. Themselves an inspiring example of America's many brilliant Lohr, his fellow officers and directors, themselves executives accomplishments, our railroads have played a stellar role in the rise of the cooperating railroads who have made possible the of this great nation. -

NYC's Weehawken Terminal

Second Section of the Century in the Post War Era - Part 2 By Dave Staplin 3rd Quarter 2016 Volume 6 Number 3 Table of Contents Modeling 2nd Sections of the Alan Schofield’s a Photographer & Modeler Century in Post WW II Era By Dave Staplin 27 Live Steam Hudson By Keith Taylor 39 Harmon Substation 6a By Alan Schofield 44 NYC’s Weehawken Terminal – Part 2 By Roger Murphy See some of his modeling. Page 44 48 Read How This Model was Developing a Model Developed for the NYCSHS By Dave Mackay 54 NYC’s Diesel Fuel Tank Cars By Seth Lakin 63 From the Cab 5 Extra Board 6 What’s New 9 NYCSHS RPO 17 Dave Mackay tells us how. Page 54 The Observation Car 65 Flight of the Century 85 Cover photos are from the articles in this edition Appeal of the NYCentral Modeler. The NYCentral Modeler . The NYCentral Modeler focuses on providing information about modeling of the railroad in all scales. This issue features articles, photos, and reviews of NYC-related models and layouts. The objective for the publication is to help members improve their ability to model the New York Central and promote modeling interests. Contact us about doing an article for us. mailto:[email protected] NYCentral Modeler 3rd Quarter 2016 2 New York Central System Historical Society The New York Central System Central Headlight, the official Historical Society (NYCSHS) was publication of the NYCSHS. organized in March 1970 by the The Central Headlight is only combined efforts of several available to members, and former employees of the New each issue contains a wealth Board of Directors York Central Railroad. -

ITC Lake Erie Connector Environmental Report

Lake Erie Connector Project Environmental Report May 2015 Prepared for: ITC Lake Erie Connector LLC Novi, Michigan Prepared by: HDR Engineering, Inc. Portland, Maine May 2015 LAKE ERIE CONNECTOR PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Title Page No. 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Purpose and Need ................................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.1 Project Purpose ........................................................................................ 1-2 1.1.2 Project Need ............................................................................................. 1-2 1.1.2.1 Power System Reliability Benefits.......................................... 1-2 1.1.2.2 Market Efficiency Benefits ..................................................... 1-3 1.1.2.3 Environmental Benefits ........................................................... 1-3 2.0 Project Description ........................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 General Project Description ................................................................................. 2-1 2.2 Erie Converter Station Description ...................................................................... 2-3 2.2.1 General Facility Location and Description, Erie Converter Station ........ 2-3 2.2.2 Construction Methods, Erie Converter Station ....................................... -

Bio-Optical Retrieval Algorithm for the Optically Shallow Waters of the Great Lakes

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Michigan Tech Research Institute Publications Michigan Tech Research Institute 2015 Bio-optical retrieval algorithm for the optically shallow waters of the Great Lakes A. D. Korosov Nansen International Environmental Research Laboratory Dmitry V. Pozdnyakov Nansen International Environmental and Remote Sensing Centre Robert A. Shuchman Michigan Technological University Michael J. Sayers Michigan Technological University Reid W. Sawtell Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/mtri_p Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Korosov, A. D., Pozdnyakov, D. V., Shuchman, R. A., Sayers, M. J., & Sawtell, R. W. (2015). Bio-optical retrieval algorithm for the optically shallow waters of the Great Lakes. IAGLR 58th Annual Conference on Great Lakes Research. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/mtri_p/73 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/mtri_p Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons ABSTRACTS International Association for Great Lakes Research ABSTRACTS 58th Annual Conference on Great Lakes Research May 25–29, 2015 University of Vermont © 2015 International Association for Great Lakes Research 4890 South State Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48108 Cover design and conference logo by Jenifer Thomas CONTENTS ABSTRACTS .......................................................................................................... 1 A ....................................................................................................................... -

April 13, 2016 CZB’S Charles Buki Seems to Believe in and Culture

CONTENTS: From the Editors The only local voice for news, arts, April 13, 2016 CZB’s Charles Buki seems to believe in and culture. Erie. Now it’s up to us to do the same. Editors-in-Chief: Brian Graham & Adam Welsh ecently, the City of Erie received the comprehensive plan Just a Thought 4 created by urban planning firm CZB. The plan arrived with Managing Editor: a letter from principal consultant Charles Buki, which we Katie Chriest “The language your soul R have included unabridged in this issue. Contributing Editors: would speak if you could Though the full plan is now publicly accessible, and though Pat Ben Speggen teach your soul to speak.” Howard included passages of this letter in his Erie Times-News Jim Wertz column on Sunday, April 10, we chose to run it in full to share its impassioned call to action with all leaders and citizens of Erie. We Contributors: Grasping Erie’s were deeply moved by what is obviously a genuine hope that Erie Lisa Austin, Civitas will find the will and courage to move forward, and we wanted Mary Birdsong Comprehensive Plan 6 you to see this language firsthand. Rick Filippi Charles Buki’s urgent letter As Buki writes, “The time has long passed when Erie had the Lisa Gensheimer to the leaders and citizens of luxury of assuming future prosperity, and of not having to make Gregory Greenleaf-Knepp hard choices. The only reality now is that future prosperity might John Lindvay Erie come from making choices few will enjoy making.” Brianna Lyle Dan Schank We Have Met the Tommy Shannon Erie’s comprehensive plan arrived with a letter Ryan Smith Raindrops and They Are from principal consultant Charles Buki, which Ti Summer Ours 9 we have included unabridged in this issue. -

Railroad Memories Auction

KEY LOCK & LANTERN Jul/Aug 2015 NEWS Issue No.34 The Bi-Monthly Digital Supplement to Key Lock & Lantern Magazine Railroad Historians Enjoy The Summer of Best of the West in 2015 KL&L Convention Steam in the East RR Memories Auction Key, Lock & Lantern A non-profit membership KEY LOCK & LANTERN corporation dedicated to the preservation of transportation history and railroad memorabilia The mission of Key, Lock & Lantern is to gather and publish information on the NEWS history of the transportation industry, The Bi-Monthly Digital Supplement to Key Lock & Lantern Magazine and to support the preservation of railroad artifacts. KL&L members have WWW.KLNL.ORG an interest in all aspects of railroad & transportation history, from research and Jul/Aug 2015 Issue #34 preservation projects to the conservation and restoration of all types of historical From the President’s Desk ...........................................................3 memorabilia. Originally formed in 1966, Key, Lock & Lantern, Inc. was officially Railroad Event Calendar...............................................................3 incorporated in 1988 as a non-profit, educational, membership corporation 2015 Key, Lock & Lantern Convention.........................................4 in the State of New Jersey, under the Best of the West in Railroad Memories Auction.........................6 provisions of Section 501(c)(3) of the United States Internal Revenue Code. Summer of Steam in the East.......................................................8 Membership is open to anyone