Argentina, 1973-1976

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/58/307 General Assembly

United Nations A/58/307 General Assembly Distr.: General 22 August 2003 Original: English Fifty-eighth session Item 119 (a) of the provisional agenda* Human rights questions: implementation of human rights instruments Status of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Optional Protocols to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Report of the Secretary-General** Summary The General Assembly, by its resolution 2200 A (XXI) of 16 December 1966, adopted and opened for signature, ratification or accession the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the First Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and expressed the hope that the Covenants and the Optional Protocol would be signed, ratified or acceded to without delay. The Assembly also requested the Secretary-General to submit to it at its future sessions reports concerning the status of ratification of the Covenants and of the Optional Protocol. In response to that request, reports on the status of the International Covenants and the Optional Protocol have been submitted annually to the Assembly since its twenty-second session in 1967. Both Covenants and the Optional Protocol were opened for signature at New York on 19 December 1966. In accordance with their respective provisions,1 the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights entered into force on 3 January 1976, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights entered * A/58/150. ** The footnote requested by the General Assembly in resolution 58/248 was not included in the submission. -

Children of Working Mothers, March 1976. Special Labor Force Report

.o 28 1125 22 20 1:1 18 6' I . 4,401. 414. DOOM= MORE 0 ED 149 853 'fP8 009 754 AIITHOR Grossman, Allyson Sherman TITLE, Children of Working Mothers, March 1976. Special Labor _Force Report 205. - BureaU of Labor Statistics 1DOL), Washington, D.G. PUB DATE Mar 76 NOTE 8p.; Tables mai' be marginally legible due to quality of print in document- JOURNAL ZIT Monthly Labor Review; p41-44 June 1977 EDRS PRICE MF=10.83 HC-$1.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Comparative Analysis; Day Care Services; Demography; *Employment Statistics; Ethnic Groups; Family Characterstics;,Family Income; Fatherless 'Family; *Mothers;' Racial Characteristics; Socioeconomic Influences; *Statistical Surieys; Tables (Data); *Tread Analysis:. *Working Parents; *Working Women ABSTRACT This Paper presents a survey of the number of mothers with children under age 17 who. were in `the work force in 1976. The , paper survey'various factors which influence these statistics: age of children, socioeconomic factOrs, ethnic and racial' characteristics, family sizei, faziily income and the availability of child care services: The statistics for 1176 are compared to data from previous years. -Tables art provided to illustrate the statistics presented in .the paper. (BD) ********44***************************i*******************************4* * Reproductibng supplied b! ERRS are the beet that can be made ,** * , from the orlginsi document. ' . ********************************************4!******44i*****************/ . ,M1 1 en-of-Working Mothers, 1976 I US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. R,DUCATION %WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEENREPRO. ,DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED 205 . FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIONORIGIN. ATING II. POINTS OR VIEW OROPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILYREPRE ent of Labor SENT OFFICIAL NATIONALINSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION ORPOLICY bor StatstIcs. -

Engineering Growth: Innovative Capacity and Development in the Americas∗

Engineering Growth: Innovative Capacity and Development in the Americas∗ William F. Maloneyy Felipe Valencia Caicedoz July 1, 2016 Abstract This paper offers the first systematic historical evidence on the role of a central actor in modern growth theory- the engineer. We collect cross-country and state level data on the population share of engineers for the Americas, and county level data on engineering and patenting for the US during the Second Industrial Revolution. These are robustly correlated with income today after controlling for literacy, other types of higher order human capital (e.g. lawyers, physicians), demand side factors, and instrumenting engineering using the Land Grant Colleges program. We support these results with historical case studies from the US and Latin America. A one standard deviation increase in engineers in 1880 accounts for a 16% increase in US county income today, and patenting capacity contributes another 10%. Our estimates also help explain why countries with similar levels of income in 1900, but tenfold differences in engineers diverged in their growth trajectories over the next century. Keywords: Innovative Capacity, Human Capital, Engineers, Technology Diffusion, Patents, Growth, Development, History. JEL: O11,O30,N10,I23 ∗Corresponding author Email: [email protected]. We thank Ufuk Akcigit, David de la Croix, Leo Feler, Claudio Ferraz, Christian Fons-Rosen, Oded Galor, Steve Haber, Lakshmi Iyer, David Mayer- Foulkes, Stelios Michalopoulos, Guy Michaels, Petra Moser, Giacomo Ponzetto, Luis Serven, Andrei Shleifer, Moritz Shularick, Enrico Spolaore, Uwe Sunde, Bulent Unel, Nico Voigtl¨ander,Hans-Joachim Voth, Fabian Waldinger, David Weil and Gavin Wright for helpful discussions. We are grateful to William Kerr for making available the county level patent data. -

Bangkok, 27 March 1976 .ENTRY INTO FORCE: 25 February 1979, In

2. CONSTITUTION OF THE ASIA-PACIFIC TELECOMMUNITY Bangkok, 27 March 1976 ENTRY. INTO FORCE: 25 February 1979, in accordance with article 18. REGISTRATION: 25 February 1979, No. 17583. STATUS: Signatories: 18. Parties: 41.1 TEXT: United Nations, Treaty Series , vol. 1129, p. 3. Note: The Constitution of the Asia-Pacific Telecommunity was adopted on 27 March 1976 by resolution 163 (XXXII)2 of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific at its thirty-second session, which took place at Bangkok, Thailand, from 24 March 1976 to 2 April 1976. The Constitution was open for signature at Bangkok from 1 April 1976 to 31 October 1976 and at the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York from 1 November 1976 to 24 February 1979. Ratification, Ratification, Acceptance(A), Acceptance(A), Participant Signature Accession(a) Participant Signature Accession(a) Afghanistan..................................................12 Jan 1977 17 May 1977 Mongolia......................................................14 Aug 1991 a Australia.......................................................26 Jul 1977 26 Jul 1977 Myanmar......................................................20 Oct 1976 9 Dec 1976 Bangladesh................................................... 1 Apr 1976 22 Oct 1976 Nauru ........................................................... 1 Apr 1976 22 Nov 1976 Bhutan..........................................................23 Jun 1998 a Nepal............................................................15 Sep 1976 12 May 1977 Brunei Darussalam3 -

The Transformation of Party-Union Linkages in Argentine Peronism, 1983–1999*

FROM LABOR POLITICS TO MACHINE POLITICS: The Transformation of Party-Union Linkages in Argentine Peronism, 1983–1999* Steven Levitsky Harvard University Abstract: The Argentine (Peronist) Justicialista Party (PJ)** underwent a far- reaching coalitional transformation during the 1980s and 1990s. Party reformers dismantled Peronism’s traditional mechanisms of labor participation, and clientelist networks replaced unions as the primary linkage to the working and lower classes. By the early 1990s, the PJ had transformed from a labor-dominated party into a machine party in which unions were relatively marginal actors. This process of de-unionization was critical to the PJ’s electoral and policy success during the presidency of Carlos Menem (1989–99). The erosion of union influ- ence facilitated efforts to attract middle-class votes and eliminated a key source of internal opposition to the government’s economic reforms. At the same time, the consolidation of clientelist networks helped the PJ maintain its traditional work- ing- and lower-class base in a context of economic crisis and neoliberal reform. This article argues that Peronism’s radical de-unionization was facilitated by the weakly institutionalized nature of its traditional party-union linkage. Although unions dominated the PJ in the early 1980s, the rules of the game governing their participation were always informal, fluid, and contested, leaving them vulner- able to internal changes in the distribution of power. Such a change occurred during the 1980s, when office-holding politicians used patronage resources to challenge labor’s privileged position in the party. When these politicians gained control of the party in 1987, Peronism’s weakly institutionalized mechanisms of union participation collapsed, paving the way for the consolidation of machine politics—and a steep decline in union influence—during the 1990s. -

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

CONFIDENTIAL GENERAL AGREEMENT ON MCDP/W/58/Rev.22 TARIFFS AND TRADE lU July 1978 Arrangement Concerning Certain Dairy Products MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Information Required by the Committee under Article IV of the Arrangement Information under the Decision of 10 May 1976 Revision For the convenience of delegations . the secretariat has prepared and updated the following summary tables3 based on communications received to date in pursuance of the Decision of 10 May 1976. 4 5 INFORMATION RECEIVED IN PURSUANCE OF THE DECISION OF 10 MAY 1976 ~ Exporter Volume Destination Date of Pries Importer participants (n. tons) contract Delivery schedule Control measure conditions of sales Port of export Port of import Age of the powder attestation Australia 10,000 Romania October, November 1976 Melbourne/Portland Constantsa 1975 Filed Canada 1,200 Yugoslavia It. 5.1976 June 1976 l/3552/Add.6 Para.10 US$245 per ton c.l.f. Montreal Rijeka September/October/November 1974 Filed 175 Taiwan 18. 6.1976 July 1976 1/3552/Add.6 Para. 6 US$270 per 0.4 f. Montreal Keelung/Kaohslung July 1976 Filed (110 m.t. 1,250 Taiwan 18. 6.1976 July to October 1976 l/3552/*dd.6 Para. 6 US$270 per c.4 f. Montreal/St. John Kaohslung June 1976 Filed 100 Taiwan 23 6.1976 July, August 1976 l/3552/Add.6 Para. 6 US$270 per c.& f. St. John Kaohslung July 1976 Filed 5,000 Bulgaria 18. 6.1976 July, August 1976 l/3552/Add.6 Para.10 US$245 per c.4 f. Montreal Varna/Bougas April/July 1975 Filed 2,000 Bulgaria 11. -

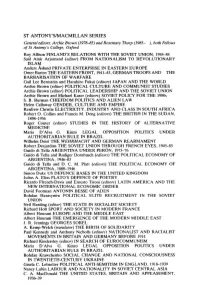

St Antony's/Macmillan Series

ST ANTONY'S/MACMILLAN SERIES General editors: Archie Brown (1978-85) and Rosemary Thorp (1985- ), both Fellows of St Antony's College, Oxford Roy Allison FINLAND'S RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1944-84 Said Amir Arjomand (editor) FROM NATIONALISM TO REVOLUTIONARY ISLAM Anders Åslund PRIVATE ENTERPRISE IN EASTERN EUROPE Orner Bartov THE EASTERN FRONT, 1941-45, GERMAN TROOPS AND THE BARBARISATION OF WARFARE Gail Lee Bernstein and Haruhiro Fukui (editors) JAPAN AND THE WORLD Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL CULTURE AND COMMUNIST STUDIES Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE SOVIET UNION Archie Brown and Michael Kaser (editors) SOVIET POLICY FOR THE 1980s S. B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Helen Callaway GENDER, CULTURE AND EMPIRE Renfrew Christie ELECTRICITY, INDUSTRY AND CLASS IN SOUTH AFRICA Robert O. Collins and FrancisM. Deng (editors) THE BRITISH IN THE SUDAN, 1898-1956 Roger Couter (editor) STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Maria D'Alva G. Kinzo LEGAL OPPOSITION POLITICS UNDER AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN BRAZIL Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Robert Desjardins THE SOVIET UNION THROUGH FRENCH EYES, 1945-85 Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERÓN, 1973-76 Guido di Tella and Rudiger Dornbusch (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1946-83 Guido di Tella and D. C. M. Platt (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1880-1946 Simon Duke US DEFENCE BASES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Julius A. Elias PLATO'S DEFENCE OF POETRY Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Ernesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER David Footman ANTONIN BESSE OF ADEN Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION Neil Harding (editor) THE STATE IN SOCIALIST SOCIETY Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST Albert Hourani THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST J. -

Argentine Government Embarrassed by Weapons Sale to Ecuador LADB Staff

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiSur Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 3-31-1995 Argentine Government Embarrassed By Weapons Sale To Ecuador LADB Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur Recommended Citation LADB Staff. "Argentine Government Embarrassed By Weapons Sale To Ecuador." (1995). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/notisur/ 11861 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiSur by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 56184 ISSN: 1060-4189 Argentine Government Embarrassed By Weapons Sale To Ecuador by LADB Staff Category/Department: Argentina Published: 1995-03-31 The alleged shipment of 75 tons of weapons from Argentina to Ecuador, apparently delivered during the five-week war between Ecuador and Peru, is proving to be an embarrassment to the government of President Carlos Saul Menem. On March 10, Menem ordered a thorough investigation into the circumstances surrounding the sale, but little progress has been made. Meanwhile, the opposition is calling for the resignation of those responsible, including Defense Minister Oscar Camilion. Argentina is one of the four guarantor countries along with the US, Chile, and Brazil of the 1942 Rio de Janeiro Protocol between Peru and Ecuador. When fighting broke out in a disputed area on the border between the two countries in January, the four guarantor countries worked diligently to broker a new peace agreement. The US declared an arms embargo against Peru and Ecuador on Feb. -

Marital Status and Living Arrangements: March 1976 U.S

CURRENT POPULATION REPORTS Population · Characteristics U.S. Department of Commerce Series P·20, No. 306 BUREAU OF THE CENSUS Issued January 1977 Marital Status and Living Arrangements: March 1976 U.S. Department of Commerce Juanita M. Kreps, Secretary BUREAU OF THE CENSUS Robert L. Hagan, Acting Director Daniel B. Levine, Associate Director for Demographic Fields POPULATION DIVISION Meyer Zitter, Chief ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by Arthur J. Norton, Chief, and Arlene F. Saluter, staff member, of the Marriage and Family Statistics Branch. Assistance was provided by Robert Grymes, Gerda Mudd, and Katherine Campbell. Overall direction was provided by Charles E. Johnson, Jr., Assistant Division Chief (Demographic and Social Statistics Programs), Population Division, and Paul C. Glick, Senior Demographer, Population Division. Sampling review was conducted by Diane Harley and Christina Gibson, Statistical Methods Division. SUGGESTED CITATION U.S. Bureau of the Census, Current Population Reports, Series P·20, No. 306, "Marital Status and Living Arrangements: March 1976," U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1977. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402, and U.S. Department of Commerce district offices. Postage stamps not acceptable; currency submitted at sender's risk. Remittances from foreign countries must be by international money order or by draft on a U.S. bank. Additional charge for foreign mailing, $14.00. All population series reports sold as a single consolidated subscription $56.00 per year. Price for this report $1.40. CURRENT POPULATION REPORTS Population Characteristics Series P-20, No. 306 Issued January 1977 Marital Status and Living Arrangements: March 1976 CONTENTS Page Introduction . -

A R G E N T I

JUJUY PARAGUAY SALTA SOUTH FORMOSA Asunción PACIFIC TUCUMÁN CHACO SANTIAGO S OCEAN NE CATAMARCA SIO DEL ESTERO MI CORRIENTES á River an LA RIOJA Par BRAZIL SANTA FE SAN JUAN CÓRDOBA ENTRE RÍOS SAN LUIS URUGUAY MENDOZA Santiago Buenos Aires ARGENTINA Montevideo LA PAMPA BUENOS AIRES CHILE NEUQUÉN RÍO NEGRO SOUTH CHUBUT ATLANTIC OCEAN SANTA CRUZ Islas Malvinas TIERRA DEL FUEGO 0 200 miles david rock RACKING ARGENTINA opular protest erupted on the streets of Argentina through the hot December nights of 2001.1 Crowds from Pthe shanty towns attacked stores and supermarkets; banging their pots and pans, huge demonstrations of mainly middle- class women—cacerolazos—marched on the city centre; the piqueteros, organized groups of the unemployed, threw up road-blocks on high- ways and bridges. Twenty-seven demonstrators died, including five shot down by the police beneath the grand baroque façades of Buenos Aires’ Plaza de Mayo. The trigger for the fury had been the IMF’s suspension of loans to Argentina, on the grounds that President Fernando De la Rúa’s government had failed to meet its conditions on public-spending cuts. There was a run on the banks, as depositors rushed to get their money out and their pesos converted into dollars. De la Rúa’s Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo slapped on a corralito, a ‘little fence’, to limit the amount of cash that could be withdrawn—leaving many people’s savings trapped in failing banks. On December 20, as the protests inten- sified, De la Rúa resigned, his helicopter roaring up over the Rosada palace and the clouds of tear gas below. -

Country Term # of Terms Total Years on the Council Presidencies # Of

Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council Elected Members Algeria 3 6 4 2004 - 2005 December 2004 1 1988 - 1989 May 1988, August 1989 2 1968 - 1969 July 1968 1 Angola 2 4 2 2015 – 2016 March 2016 1 2003 - 2004 November 2003 1 Argentina 9 18 15 2013 - 2014 August 2013, October 2014 2 2005 - 2006 January 2005, March 2006 2 1999 - 2000 February 2000 1 1994 - 1995 January 1995 1 1987 - 1988 March 1987, June 1988 2 1971 - 1972 March 1971, July 1972 2 1966 - 1967 January 1967 1 1959 - 1960 May 1959, April 1960 2 1948 - 1949 November 1948, November 1949 2 Australia 5 10 10 2013 - 2014 September 2013, November 2014 2 1985 - 1986 November 1985 1 1973 - 1974 October 1973, December 1974 2 1956 - 1957 June 1956, June 1957 2 1946 - 1947 February 1946, January 1947, December 1947 3 Austria 3 6 4 2009 - 2010 November 2009 1 1991 - 1992 March 1991, May 1992 2 1973 - 1974 November 1973 1 Azerbaijan 1 2 2 2012 - 2013 May 2012, October 2013 2 Bahrain 1 2 1 1998 - 1999 December 1998 1 Bangladesh 2 4 3 2000 - 2001 March 2000, June 2001 2 Country Term # of Total Presidencies # of terms years on Presidencies the Council 1979 - 1980 October 1979 1 Belarus1 1 2 1 1974 - 1975 January 1975 1 Belgium 5 10 11 2007 - 2008 June 2007, August 2008 2 1991 - 1992 April 1991, June 1992 2 1971 - 1972 April 1971, August 1972 2 1955 - 1956 July 1955, July 1956 2 1947 - 1948 February 1947, January 1948, December 1948 3 Benin 2 4 3 2004 - 2005 February 2005 1 1976 - 1977 March 1976, May 1977 2 Bolivia 3 6 7 2017 - 2018 June 2017, October -

April 1975 - March 1976

ANNUAL REPORT April 1975 - March 1976 J.M. Gill Warwick Research Unit for the Blind University of Warwick Coventry CV4 7AL March 1976 Contents Page 1. Introduction 2 2. Present Personnel 3 3. Transcription of Short Documents 3 4. Braille Bank Statements 6 5. Computer and Control Abstracts 7 6. Psychological Abstracts 8 7. Educational Abstracts 8 8. Compositor's Tapes 9 9. International Register of Research 9 10. Braille Automation Newsletter 10 11. Soviet Union 10 12. Funding 10 13. Publications and Reports 12 1. Introduction This first Annual Report has been produced as a general brief survey of the activities of the Research Unit. It is hoped it will prove appropriate for a wide range of readers including those who have generously given financial assistance, advice or lent equipment. Significant progress has been made on techniques for producing braille with particular emphasis on the utilisation of information already in digital form. Close contacts have been maintained with a large section of the visually handicapped community. The last twelve months have been dominated by acute financial problems which have now been resolved in the short term. The Unit was reduced from four to two full-time staff but it can now continue at this size for another year. - 3 - 2. Present Personnel Prof. J.L. Douce part-time supervisor of the Unit Dr. J.M. Gill full-time senior research fellow Mrs. L.C. Wooldridge full-time secretary J.B. Humphreys part-time programmer (6 hours per week) Mrs. P.A. Foxon part-time research assistant (6 hours per week) Students from the Department of Engineering are also involved in specific projects.