Number 115 ARGENTINA at the CROSSROADS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argentine History: from Pre-Colonial Times Through the 20Th Century

Syllabus 2016 Argentine History: From pre-colonial times through the 20th century Dr. Juan Francisco Martínez Peria [CEL – UNSAM] Fridays 2:00 – 6:00 pm Total Load: 64 hours Course Description This course aims to delve into the economic, cultural, social, and political history of Argentina, since the pre-colonial period through the last decades of the twentieth century. The course will provide an overview of the mayor processes that marked the historical development of this country, examining at the same time the strong bonds with the other Latin American nations and the complex relations with the major hegemonic powers. In the first place, we will study the societies of the native peoples of Argentina and the sufferings they experienced due to the Spanish colonization. Next, we will analyze the economic, social, political, and cultural situation of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata under Spanish rule and its crisis in the XIX century. Subsequently, we will study the Argentine independence movement, examining its ties with the rest of the Spanish American Revolutions. In fourth place, we will study the postcolonial era and the civil wars between Buenos Aires’ elite and the provinces, taking in account the experiences of the Rosistas and Urquicistas Confederations. Next, we will examine the liberal conservative order, the state building process, the immigration process, and the emergence of the labor movement and the radical party. Afterwards, we will analyze the crisis of the conservative order, the radical governments, and the brief liberal conservative restoration. Following, we will examine the Peronist governments, and the post Peronist crisis studying the social and political turmoil that agitated Argentina during the 50´s, 60´s 70´s. -

Doc CADAL 16 English

The Political Origins of the Argentine Crisis By Mauricio Rojas The ills that afflict Argentina are not simple or superficial, and the solutions to its problems require a more serious diagnosis than the one given by those who look for a scapegoat to blame this one-time promising country’s woes on. Understanding this today is more D important than ever, because the country is going through a characteristic period of recovery and hope that appears from time to time, like a pause between violent swells of crises. Now is the O time to start facing these long-standing problems, before they overwhelm us again. C U This document is a revised version of the preface to the second Spanish edition of «History of the Argentine Crisis». The book was originally published in Swedish and M later translated and published in English and Portuguese. The first Spanish edition was published by CADAL and TIMBRO in December 2003. E N T Mauricio Rojas was born in Santiago de Chile in 1950 and lives in Sweeden since 1974. He is a Member of the Sweeden Parlament, Associate Professor in the Department of Economic O History at Lund University, Vice President of Timbro and Director of Timbro’s Center for Welfare Reform. He is author of a dozen books, among them, The Sorrows of Carmencita, Argentina’s crisis in a historial perspective (2002), Millennium Doom, Fallacies about the end of work (1999). Beyond the S welfare state. Sweden and the quest for a post-industrial Year II Number 16 welfare model (2001) and The rise and fall of the swedish May 21st., 2004 model (1998). -

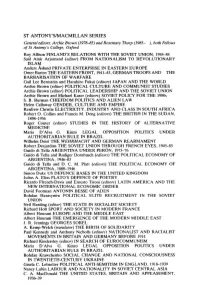

St Antony's/Macmillan Series

ST ANTONY'S/MACMILLAN SERIES General editors: Archie Brown (1978-85) and Rosemary Thorp (1985- ), both Fellows of St Antony's College, Oxford Roy Allison FINLAND'S RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1944-84 Said Amir Arjomand (editor) FROM NATIONALISM TO REVOLUTIONARY ISLAM Anders Åslund PRIVATE ENTERPRISE IN EASTERN EUROPE Orner Bartov THE EASTERN FRONT, 1941-45, GERMAN TROOPS AND THE BARBARISATION OF WARFARE Gail Lee Bernstein and Haruhiro Fukui (editors) JAPAN AND THE WORLD Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL CULTURE AND COMMUNIST STUDIES Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE SOVIET UNION Archie Brown and Michael Kaser (editors) SOVIET POLICY FOR THE 1980s S. B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Helen Callaway GENDER, CULTURE AND EMPIRE Renfrew Christie ELECTRICITY, INDUSTRY AND CLASS IN SOUTH AFRICA Robert O. Collins and FrancisM. Deng (editors) THE BRITISH IN THE SUDAN, 1898-1956 Roger Couter (editor) STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Maria D'Alva G. Kinzo LEGAL OPPOSITION POLITICS UNDER AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN BRAZIL Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Robert Desjardins THE SOVIET UNION THROUGH FRENCH EYES, 1945-85 Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERÓN, 1973-76 Guido di Tella and Rudiger Dornbusch (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1946-83 Guido di Tella and D. C. M. Platt (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1880-1946 Simon Duke US DEFENCE BASES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Julius A. Elias PLATO'S DEFENCE OF POETRY Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Ernesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER David Footman ANTONIN BESSE OF ADEN Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION Neil Harding (editor) THE STATE IN SOCIALIST SOCIETY Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST Albert Hourani THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST J. -

The Rise and Fall of Argentina

Spruk Lat Am Econ Rev (2019) 28:16 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40503-019-0076-2 Latin American Economic Review RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The rise and fall of Argentina Rok Spruk* *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract School of Economics I examine the contribution of institutional breakdowns to long-run development, and Business, University of Ljubljana, Kardeljeva drawing on Argentina’s unique departure from a rich country on the eve of World ploscad 27, 1000 Ljubljana, War I to an underdeveloped one today. The empirical strategy is based on building Slovenia a counterfactual scenario to examine the path of Argentina’s long-run development in the absence of breakdowns, assuming it would follow the institutional trends in countries at parallel stages of development. Drawing on Argentina’s large historical bibliography, I have identifed the institutional breakdowns and coded for the period 1850–2012. The synthetic control and diference-in-diferences estimates here suggest that, in the absence of institutional breakdowns, Argentina would largely have avoided the decline and joined the ranks of rich countries with an income level similar to that of New Zealand. Keywords: Long-run development, New institutional economics, Political economy, Argentina, Applied econometrics JEL Classifcation: C23, K16, N16, N46, O43, O47 1 Introduction On the eve of World War I, the future of Argentina looked bright. Since its promulga- tion of the 1853 Constitution, Argentina had experienced strong economic growth and institutional modernization, which had propelled it into the ranks of the 10 wealthi- est countries in the world by 1913. In the aftermath of the war, Argentina’s income per capita fell from a level approximating that of Switzerland to its current middle-income country status. -

La Prensa and Liberalism in Argentina, 1930-19461 Jorge Nállim University of Manitoba

An Unbroken Loyalty in Turbulent Times: La Prensa and Liberalism in Argentina, 1930-19461 JORGE NÁLLIM University of Manitoba In recent years, a growing body of scholarship has revised one of the most controversial periods in Argentine history: the sixteen years between the mi- litary coup of September 1930 and the presidential election of Juan Perón in 1946. These years have been traditionally interpreted as a transition period, a “prelude” to the emergence of Peronism, characterized by the decadence of the nineteenth-century liberal republic in a context of political and ideological crisis and economic and social transformation. While acknowledging some of those features, new studies emphasize the blurred political and ideological boundaries of the main political and social actors and locate them within the broader histo- rical framework of the interwar years. For example, they show that the Radical and Socialist parties and the conservative groups that gathered in the ruling Concordancia coalition were deeply divided and far from being ideologically homogeneous, and that varied positions on state economic intervention, free trade, and industrialization generated both sharp intra-party differences as well as cross-party coincidences.2 This new historiography offers a particularly fruitful context to explore one of the most important national newspapers in this period, La Prensa. Founded in 1869 by José C. Paz in the city of Buenos Aires, La Prensa eventually achieved a large national circulation and a reputation as a “serious press,” which made it widely accepted as a reliable source of information and a frequent reference in congressional debates. Firmly controlled by the Paz family, the newspaper and its owners prospered during Argentina’s elitist liberal republic which lasted [email protected] E.I.A.L., Vol. -

A Brief History of Argentina

A Brief History of ArgentinA second edition JonAtHAn c. Brown University of Texas at Austin A Brief History of Argentina, Second Edition Copyright © 2010, 2003 by Lexington Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Brown, Jonathan C. (Jonathan Charles), 1942– A brief history of Argentina / Jonathan C. Brown. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8160-7796-0 1. Argentina—History. I. Title. F2831.B88 2010 982—dc22 2010004887 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Excerpts included herewith have been reprinted by permission of the copyright holders; the author has made every effort to contact copyright holders. The publishers will be glad to rectify, in future editions, any errors or omissions brought to their notice. Text design by Joan M. McEvoy Maps and figures by Dale Williams and Patricia Meschino Composition by Mary Susan Ryan-Flynn Cover printed by Art Print, Taylor, Pa. Book printed and bound by Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group, York, Pa. -

Doing Business in Argentina

www.pwc.com/ar Doing Business in Argentina 2019 onwards www.pwc.com.ar Contents 4. Geographical and demographical background 10. Investment and Challenges in Argentina 14. Form of Foreign Investment / Structuring the Deal 16. Foreign Trade and Customs Regulations 20. Tax system 31. Reference information 32. Contacts Geographical & demographical background 4 Location The Republic of Argentina1 is located in South America, between latitudes 23°S (Tropic of Capricorn) and 55°S (Cape Horn). The Andes separates the country from Chile to the west and Bolivia to the northwest; Paraguay lies directly to the north, with Brazil, Uruguay and the South Atlantic Ocean to the east. Brief history of the country The history of Argentina began in 1776 with the creation of Once democracy returned in the early eighties, the the Virreinato del Río de la Plata, the name given to the country faltered in finding a clear path to growth. GPD colonial territories of Spain. In 1810, Argentina initiated a was stagnant, as in most Latin American countries, with process that led to independence in 1816, although for over episodes of hyperinflation toward the end of the decade. sixty years there were internal battles for control of income At the beginning of the nineties, Argentina adopted a from Customs, monopolized by the Province of Buenos convertibility plan with a pegged exchange rate. Many of Aires. the country’s public utility companies were privatized After this period of civil war, the country began a during this decade. process of modernization in 1880, with the creation of After the 2001-2002 economic and social crisis, new public institutions and efforts to build a foundation convertibility and the pegged exchange rate were to incorporate the country into the international system abandoned and replaced with a controlled floating rate of division of labor as an agricultural commodity system. -

E.0/W 1 TAGS: Otrar OUIPT AR SUBJECT: Travel of Assistant Secretary Enders —Overview Ctf

~iol o b mr/f 0 L" +Jts /hyt INOICATE ~ COLLECT ~ CHARGE TO Fttom CL Amembassy BUENOS AI S 12065 E.O. A~ GDS 3/3/88 (Ruser, C.W, ) OR-M E.0/W 1 TAGS: OTRAr OUIPT AR SUBJECT: Travel of Assistant Secretary Enders —Overview ctf. Aroassyina ACTION: Secstate WASHDC IMMEDIATE .lr DEPT. OF STATE, A/RPS/IPS targaret P. Grafeld, Director INFO: Amembassy CARACAS PRIORITY +Release ( )Excise ( )DenY remotion(s)I ' BUENOS AIRES lclasslfy: ( ) In Part (p In Full 1225 'Tssify as ( ) Extend as ( ) Downgrade to CARACAS FOR, ASSISTANT SECRETARY ENDERS on 1. - entire text AMB DCM 2 ~ summary: The two major topics POL-2 Argentine offichls will ECON wish to discuss are the situation in America USIS Central and DAO Bolivia, which they see as threatening Argentina's own secu- Chron rity, and the Alemann economic program on which the Galtieri government's future so heavily depends. Galtieri and his col- laborators seek close cooperation with the United States, es- philosophicall pecially in the security area and are/ inclined toward the West, But the GOA continues in the NAM impelled by the need for protection on human rights in international fora and by the search for support on the Malvinas/Falklands and Beagle problems. Our principal difference is in the nuclear field. Other fhctors in our relationship are human )RAFTEO BY GRAFTING GATE TEL. EAT CONTENTS ANO CLASSIFICATION APDROV EO B'Yr R er/AMBtHWShlaudemant -3/3/82 202 AEBS Shlaudeman CLEQ ES a3 85F48 51/214 OPTIONAL FORM 153 CLASSIFICATION rFormerty FS-e131 SOIS3-101 ueouery tete oeot ot stete "b 4 / XW I i':".Ct 3 I MRN :4'Nir AJI "2":2 rights, differences on Law of the Seay occasionally conflicting interests in UN fora and various economic issues such as sugar and our graduation policy in the MDBs, Involvement in Central America carries a poli- tical price for the GOA domestically. -

Perón: the Ascent and Decline to Power

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-2014 Perón: the Ascent and Decline to Power Annelise N. Marshall Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Latin American History Commons, and the Political History Commons Recommended Citation Marshall, Annelise N., "Perón: the Ascent and Decline to Power" (2014). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 17. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/17 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Perón: the Ascent and Decline to Power By Annelise N. Marshall An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. John Rector, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2014 Abstract Juan Perón was the democratically elected president of Argentina from 1946 until he was deposed by a military coup in 1955. He remained in exile for almost twenty years before being reelected in 1973. At different times the Argentine people considered him a crusader for social justice, a tyrant, or a savior. Today Peronism, the political ideology based on Perón’s principles and policies, still fluctuates in popularity, and this project seeks to communicate a fuller understanding of how political ideologies and politicians themselves cycle in and out of popularity through study of Perón. -

The Rise and Fall of Argentina

POLICY BRIEF The Rise and Fall of Argentina Rok Spruk August 2018 On the eve of World War I, the future of Argentina seemed bright. From the adoption of the con- stitution in 1853 to the onset of World War I, Argentina underwent a period of economic excep- tionalism known as the Belle Époque.1 By 1896, Argentina achieved per capita income parity with the United States and attained a considerably higher level of prosperity than France, Germany, Italy, and Spain.2 Strong economic growth and institutional reforms positioned Argentina among the top 10 countries by 1913 in terms of per capita GDP.3 Some scholars have called 19th-century Buenos Aires “Chicago on Rio de la Plata,” given the historical similarities between both cities.4 Ninteenth century Buenos Aires boasted the highest literacy rates in Latin America,5 unprec- edented European immigration,6 and rapid modernization of infrastructure.7 It seems that Argentina briskly moved the “lever of riches” in less than half a century.8 In 1913, Argentina’s per capita income stood at 72 percent of the US level.9 In 2010, Argentina achieved barely a third of US level. In 1860, Argentina needed about 55 years to attain the per capita income level of Switzerland. Today Argentina would need more than 90 years to achieve the Swiss level of prosperity. How could a society that achieved astonishing wealth and splendor in less than half a century move from being a developed country to being an underdeveloped one? The most obvious question to ask is, What went wrong? The answer lies in a lack of inclusive and participa- tory robust legal and institutional framework that would have prevented the reforms from being undermined. -

The Failed Invigoration of Argentina's Constitution: Presidential Omnipotence, Repression, Instability, and Lawlessness in Argentine History, 39 U

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 7-1-2008 The aiF led Invigoration of Argentina's Constitution: Presidential Omnipotence, Repression, Instability, and Lawlessness in Argentine History Mugambi Jouet Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Mugambi Jouet, The Failed Invigoration of Argentina's Constitution: Presidential Omnipotence, Repression, Instability, and Lawlessness in Argentine History, 39 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 409 (2008) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol39/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 409 ARTICLES The Failed Invigoration of Argentina's Constitution: Presidential Omnipotence, Repression, Instability, and Lawlessness in Argentine History Mugambi Jouet* I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 410 II. ARGENTINE HYPERPRESIDENTIALISM VERSUS THE CONSTITUTIONAL IDEAL OF LIMITED GOVERNMENT P OW ER ............................................... 412 III. 1860-1930: DEMOCRATIZATION DURING THE GOLDEN AGE ................................................. 416 IV. 1930-1983: A SOCIETY AT WAR ....................... 421 A. Violence and -

The International Monetary Fund and Latin America: the Argentine

The International Monetary Fund and Latin America The International Monetary Fund and Latin America THE ARGENTINE PUZZLE IN CONTEXT CLAUDIA KEDAR TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia TEMPLE UNIVERSITY PRESS Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 www.temple.edu/tempress Copyright © 2013 by Temple University All rights reserved Published 2013 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kedar, Claudia, 1968– Th e International Monetary Fund and Latin America : the Argentine puzzle in context / Claudia Kedar. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4399-0909-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4399-0911-9 (e-book) 1. International Monetary Fund—Argentina. 2. Financial crises—Argentina—History. 3. Debts, External—Argentina. 4. Argentina—Foreign economic relations. 5. Argentina— Economic policy. I. Title. HC175.K43 2013 332.1'520982—dc23 2012017782 Th e paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992 Printed in the United States of America 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 For Sandy, with all my love Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 Multilateralism from the Margins: Latin America and the Founding of the IMF, 1942–1945 11 2 It Takes Th ree to Tango: Argentina, the Bretton Woods Institutions, and the United States, 1946–1956 32 3 Dependency in the Making: Th e First Loan Agreement and the Consolidation of the Formal Relationship with the IMF, 1957–1961 55 4 Fluctuations in the Routine of Dependency: Argentine–IMF Relations in a Decade of Political Instability, 1962–1972 88 5 All Regimes Are Legitimate: Th e IMF’s Relations with Democracies and Dictatorships, 1973–1982 119 6 Routine of Dependency or Routine of Detachment? Looking for a New Model of Relations with the IMF 151 Conclusions 184 Notes 191 References 233 Index 245 Acknowledgments his book is the result of many years of exploring and analyzing the Inter- national Monetary Fund (IMF), one of the most central and polemical T players in the current global economy.