Nautical Chart User's Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NYS Coast Pilot 6

CoUNITEDas STATESt Pilot® Great Lakes: Lakes Ontario, Erie, Huron, Michigan, Superior and St. Lawrence River 2018 (48th) Edition This edition cancels the 47th Edition and includes all previously published corrections. Weekly updates to this edition are available at nauticalcharts.noaa.gov/publications/coast-pilot/index.html They are also published in the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) U.S. Notice to Mariners. U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration RDML Timothy Gallaudet, Ph.D., USN Ret., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere National Ocean Service Nicole R. LeBoeuf, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Ocean Services and Coastal Zone Management II U.S. Coast Pilot 6 Pilot Coast U.S. 90° 88° 86° 84° 82° 80° 78° 76° 74° 72° Coast Pilot 6 – Chapter Index Chapter 4 – St. Lawrence River Above St. Regis 48° Chapter 5 – Lake Ontario Chapter 6 – Lake Erie MINNESOTA Chapter 7 – Detroit River LAKE SUPERIOR Chapter 8 – Lake St. Clair 13 Chapter 9 – St. Clair River Duluth ONTARIO Chapter 10 – Lake Huron Chapter 11 – Lake Michigan Ashland Sault St. Marie Chapter 12 – St. Marys River Chapter 13 – Lake Superior Marquette 12 46° Chapter 14 – Hudson River, New York Canals and Lake Champlain Montreal G E L O A R K G 4 I E A N R H E B V A I N U R Y E A C R N E G O R W I A N L . Green Bay H T S WISCONSIN C I 10 NEW Y ORK 44° M E K LAKE ONTARIO 5 A Toronto L Muskegon Bay City Milwaukee Syracuse Bu alo MICHIGAN 8 9 14 Detroit 11 LAKE ERIE 42° 7 Erie Chicago 6 P ENNSYLV ANIA Toledo Cleveland New York City 16 DEC2018 ILLINOIS INDIANA OHIO 16 DEC 2018 ¢ Preface III Preface he United States Coast Pilot is published by the National Ocean Service (NOS), National TOceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), pursuant to the Act of 6 August 1947 (33 U.S.C. -

Aids to Navigation Manual – Administration, COMDTINST M16500.7A

Aids to Navigation Manual Administration 02 MAR 2005 COMDTINST M16500.7A Commandant US Coast Guard Stop 7418 United States Coast Guard 2703 Martin Luther King Jr Ave, SE Washington DC 20593-7418 Staff Symbol: CG-NAV-1 Phone: (202) 372-1551 Fax: (202) 372-8358 COMDTCHANGENOTE 16500 23 FEB 2015 COMMANDANT CHANGE NOTICE 16500 Subj: CH-2 TO AIDS TO NAVIGATION MANUAL – ADMINISTRATION COMDTINST M16500.7A 1. PURPOSE. To provide changes to the Coast Guard’s Aids to Navigation Manual – Administration, COMDTINST M16500.7A. 2. ACTION. All Coast Guard unit commanders, commanding officers, officers-in-charge, deputy/assistant commandants, and chiefs of headquarters staff elements shall comply with the provisions of this Commandant Change Notice. Internet release is authorized. 3. DIRECTIVES AFFECTED. With the incorporation of this Commandant Change Notice, the Coast Guard’s Aids to Navigation Manual – Administration, COMDTINST M16500.7A is updated. 4. DISCLAIMER. This guidance is not a substitute for applicable legal requirements, nor is it itself a rule. It is intended to provide operational guidance for Coast Guard personnel and is not intended to nor does it impose legally-binding requirements on any party outside the Coast Guard. 5. MAJOR CHANGES. The Commandant Change Notice announces the Coast Guard will no longer print copies of the Coast Guard Light Lists. The following Coast Guard Light Lists will remain available on the Coast Guard Navigation Center (NAVCEN) website at http://www.navcen.uscg.gov/?pageName=lightLists. Light List Vol. 1- Atlantic Coast from St. Croix River, ME to Shrewsbury River, NJ, COMDTPUB P16502.1 Light List Vol. -

MARS an Overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera Science

MARS MARS INFORMATICS The International Journal of Mars Science and Exploration Open Access Journals Science An overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera science investigation Michael C. Malin1, Kenneth S. Edgett1, Bruce A. Cantor1, Michael A. Caplinger1, G. Edward Danielson2, Elsa H. Jensen1, Michael A. Ravine1, Jennifer L. Sandoval1, and Kimberley D. Supulver1 1Malin Space Science Systems, P.O. Box 910148, San Diego, CA, 92191-0148, USA; 2Deceased, 10 December 2005 Citation: Mars 5, 1-60, 2010; doi:10.1555/mars.2010.0001 History: Submitted: August 5, 2009; Reviewed: October 18, 2009; Accepted: November 15, 2009; Published: January 6, 2010 Editor: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University Reviewers: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University; R. Aileen Yingst, University of Wisconsin Green Bay Open Access: Copyright 2010 Malin Space Science Systems. This is an open-access paper distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: NASA selected the Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) investigation in 1986 for the Mars Observer mission. The MOC consisted of three elements which shared a common package: a narrow angle camera designed to obtain images with a spatial resolution as high as 1.4 m per pixel from orbit, and two wide angle cameras (one with a red filter, the other blue) for daily global imaging to observe meteorological events, geodesy, and provide context for the narrow angle images. Following the loss of Mars Observer in August 1993, a second MOC was built from flight spare hardware and launched aboard Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) in November 1996. -

Martian Crater Morphology

ANALYSIS OF THE DEPTH-DIAMETER RELATIONSHIP OF MARTIAN CRATERS A Capstone Experience Thesis Presented by Jared Howenstine Completion Date: May 2006 Approved By: Professor M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Professor Christopher Condit, Geology Professor Judith Young, Astronomy Abstract Title: Analysis of the Depth-Diameter Relationship of Martian Craters Author: Jared Howenstine, Astronomy Approved By: Judith Young, Astronomy Approved By: M. Darby Dyar, Astronomy Approved By: Christopher Condit, Geology CE Type: Departmental Honors Project Using a gridded version of maritan topography with the computer program Gridview, this project studied the depth-diameter relationship of martian impact craters. The work encompasses 361 profiles of impacts with diameters larger than 15 kilometers and is a continuation of work that was started at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston, Texas under the guidance of Dr. Walter S. Keifer. Using the most ‘pristine,’ or deepest craters in the data a depth-diameter relationship was determined: d = 0.610D 0.327 , where d is the depth of the crater and D is the diameter of the crater, both in kilometers. This relationship can then be used to estimate the theoretical depth of any impact radius, and therefore can be used to estimate the pristine shape of the crater. With a depth-diameter ratio for a particular crater, the measured depth can then be compared to this theoretical value and an estimate of the amount of material within the crater, or fill, can then be calculated. The data includes 140 named impact craters, 3 basins, and 218 other impacts. The named data encompasses all named impact structures of greater than 100 kilometers in diameter. -

142 Subpart B—The U.S. Aids to Navigation System

§ 62.3 33 CFR Ch. I (7–1–19 Edition) § 62.3 Definition of terms. Subpart B—The U.S. Aids to Certain terms as used in this sub- Navigation System chapter are defined as follows: (a) Aid to Navigation. The term aid to § 62.21 General. navigation means any device external (a) The navigable waters of the to a vessel or aircraft intended to as- United States and non-navigable State sist a navigator to determine position waters after December 31, 2003, are or safe course, or to warn of dangers or marked to assist navigation using the obstructions to navigation. U.S. Aids to Navigation System, a sys- (b) Commerce. The term commerce, in tem consistent with the International addition to general, national and inter- Association of Lighthouse Authorities national trade and commerce of the (IALA) Maritime Buoyage System. The United States, includes trade and trav- IALA Maritime Buoyage System is fol- el by seasonal passenger craft (marine lowed by most of the world’s maritime and air), yachts, houseboats, fishing nations and will improve maritime boats, motor boats, and other craft, safety by encouraging conformity in whether or not operated for hire or buoyage systems worldwide. IALA profit. buoyage is divided into two regions (c) Commandant. The term Com- made up of Region A and Region B. All mandant means the Commandant of navigable waters of the United States the Coast Guard. follow IALA Region B, except U.S. pos- (d) District Commander. The term Dis- sessions west of the International Date trict Commander means the com- Line and south of 10 degrees north lati- mander of a Coast Guard District. -

Ocean City, NJ on in Real Estate the Map for More Than Sales and Rentals Over 10,000 Leases Per Year 43 Years

US POSTAGE PAID MAIL PERFECT Official Visitors Guide 2011 PRSRT STD BERGER OCEAN CITY New Jersey Ocean City Regional REALTY Chamber of Commerce www.oceancityvacation.com Leon K. Grisbaum - Owner 1-800-BEACH-NJ Mark Soifer, Ocean City’s Leader “America’s Greatest Ocean City Publicist Family Resort” Putting Ocean City, NJ on In Real Estate the map for more than Sales and Rentals Over 10,000 leases per year 43 years. Over 2,500 rental properties PLUS Follow his weekly column Largest # of Full-Time every Thursday on Rental/Sale Agents and Office Support Staff www.OceanCityVacation.com VISIT ONE OF OUR 4 OFFICES 3160 Asbury Ave. 133 S. Shore Rd. Ocean City, NJ Marmora, NJ 1-888-399-0076 1-609-390-9300 17th & The Boardwalk 55th & Haven Ave. Over 30 Rides! OCC11 Ocean City, NJ Ocean City, NJ 1515 FREEFREE RideRide TicketsTickets plus 1-888-579-0095 1-800-399-3484 Money Saving Coupons with purchase of FAMILY BOOK • Offer good until 10/10/11 Or Online at Our Tickets Playland’sPlayland’s CastawayCastaway CoveCove www.bergerrealty.com NEVER EXPIRE!!! 10th & Boardwalk • OCNJ • oceancityfun.com MUST PRESENT THIS COUPON FOR BONUS OFFER • CANNOT BE COMBINED WITH ANY OTHER OFFER Photography - Don Kravitz Don - Photography POINTS OF INTEREST 1 Airport 2 Bayside Center, 520 Bay Avenue 3 Boardwalk 4 Boat Ramp, Tennessee Avenue 5 City Hall Annex, 901 Asbury Avenue 6 City Hall, 861 Asbury Avenue 7 Cultural-Aquatic & Fitness Center, 1701 Simpson Library, Art Center, Historical Museum 8 Golf Course, 2600 Bay Avenue 9 Humane Society, 1 Shelter Rd 10 Information Centers a. -

Aids to Navigation Manual – Technical, Comdtinst M16500.3A

Commandant 2100 Second St, SW Stop 7901 United States Coast Guard Washington DC 20593-7901 Staff Symbol: CG-432 Phone: (202) 475-5629 FAX: (202) 475-5959 Email: [email protected] COMDTNOTE 16500 APR 06 2010 COMMANDANT NOTICE 16500 CANCELLED: APR 06 2011 Subj: CH-7 TO AIDS TO NAVIGATION MANUAL – TECHNICAL, COMDTINST M16500.3A 1. PURPOSE. This Notice promulgates changes to the Aids to Navigation Manual, Technical COMDTINST M16500.3A. 2. ACTION. All Coast Guard unit commanders, commanding officers, officers-in-charge, deputy/assistant commandants, and chiefs of headquarters staff elements shall comply with the provisions of this Manual. Internet release is authorized. 3. PROCEDURES. a. The change consists of 64 pages. Remove & insert the following pages: Remove Insert 2-11 and 2-12 2-11 and 2-12 2-35 and 2-36 2-35 and 2-36 2-169 and 2-170 2-169 and 2-170 Chapter 6 Chapter 6 9-13 and 9-14 9-13 and 9-14 9-73 thru 9-78 9-73 thru 9-78 9-81 thru 9-84 9-81 thru 9-84 9-89 and 9-90 9-89 and 9-90 b. Units that have not received COMDTINST M16500.3A, Aids to Navigation Manual – Technical, but have received this change cannot requisition a copy of the manual as it is out of print. The manual is available through the CG directives system on-line and will be reprinted with all changes 1 through 7 included. DISTRIBUTION – SDL No. 155 a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z A 2 2 2 2 2 2 B 3 2 10 1 C 2 1 2 D 1 E F G H NON-STANDARD DISTRIBUTION: C:i Stations Burlington, St. -

Map Projections Paper 4 (Th.) UNIT : I ; TOPIC : 3 …Introduction

FOR SEMESTER 3 GE Students , Geography Map Projections Paper 4 (Th.) UNIT : I ; TOPIC : 3 …Introduction Prepared and Compiled By Dr. Rajashree Dasgupta Assistant Professor Dept. of Geography Government Girls’ General Degree College 3/23/2020 1 Map Projections … The method by which we transform the earth’s spheroid (real world) to a flat surface (abstraction), either on paper or digitally Define the spatial relationship between locations on earth and their relative locations on a flat map Think about projecting a see- through globe onto a wall Dept. of Geography, GGGDC, 3/23/2020 Kolkata 2 Spatial Reference = Datum + Projection + Coordinate system Two basic locational systems: geometric or Cartesian (x, y, z) and geographic or gravitational (f, l, z) Mean sea level surface or geoid is approximated by an ellipsoid to define an earth datum which gives (f, l) and distance above geoid gives (z) 3/23/2020 Dept. of Geography, GGGDC, Kolkata 3 3/23/2020 Dept. of Geography, GGGDC, Kolkata 4 Classifications of Map Projections Criteria Parameter Classes/ Subclasses Extrinsic Datum Direct / Double/ Spherical Triple Surface Spheroidal Plane or Ist Order 2nd Order 3rd Order surface of I. Planar a. Tangent i. Normal projection II. Conical b. Secant ii. Transverse III. Cylindric c. Polysuperficial iii. Oblique al Method of Perspective Semi-perspective Non- Convention Projection perspective al Intrinsic Properties Azimuthal Equidistant Othomorphic Homologra phic Appearance Both parallels and meridians straight of parallels Parallels straight, meridians curve and Parallels curves, meridians straight meridians Both parallels and meridians curves Parallels concentric circles , meridians radiating st. lines Parallels concentric circles, meridians curves Geometric Rectangular Circular Elliptical Parabolic Shape 3/23/2020 Dept. -

Gulf of Riga (Latvia)

EUROSION Case Study GULF OF RIGA (LATVIA) Contact: Ramunas POVILANSKAS 31 EUCC Baltic Office Tel: +37 (0)6 312739 or +37 (0)6 398834 e-mail: [email protected] 1 EUROSION Case Study 1. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA The length of the Latvian coastline along the Baltic proper and the Gulf of Riga is 496 km. Circa 123 km of the coastline is affected by erosion. The case area ‘Gulf of Riga’ focuses on coastal development within the Riga metropolitan area, which includes the coastal zone of two urban municipalities (pilsetas) – Riga and Jurmala (Figure 1). Riga is the capital city of Latvia. It is located along the lower stream and the mouth of the Daugava river. Its several districts (Bulli, Daugavgriva, Bolderaja, Vecdaugava, Mangali and Vecaki) lie in the deltas of Daugava and Lielupe rivers and on the Gulf of Riga coast. Jurmala municipality is adjacent to Riga from the west. It stretches ca. 30 km along the Gulf of Riga. It is the largest Latvian and Eastern Baltic seaside resort. 1.1 Physical process level 1.1.1 Classification According to the coastal typology adopted for the EUROSION project, the case study area can be described as: 3b. Wave-dominated sediment. Plains. Microtidal river delta. Within this major coastal type several coastal formations and habitats occur, including the river delta and sandy beaches with bare and vegetated sand dunes. Fig. 1: Location of the case study area. 1.1.2 Geology Recent geological history of the case area since the end of the latest Ice Age (ca. -

Depth Measuring Techniques

EM 1110-2-1003 1 Jan 02 Chapter 9 Single Beam Acoustic Depth Measurement Techniques 9-1. General Scope and Applications Single beam acoustic depth sounding is by far the most widely used depth measurement technique in USACE for surveying river and harbor navigation projects. Acoustic depth sounding was first used in the Corps back in the 1930s but did not replace reliance on lead line depth measurement until the 1950s or 1960s. A variety of acoustic depth systems are used throughout the Corps, depending on project conditions and depths. These include single beam transducer systems, multiple transducer channel sweep systems, and multibeam sweep systems. Although multibeam systems are increasingly being used for surveys of deep-draft projects, single beam systems are still used by the vast majority of districts. This chapter covers the principles of acoustic depth measurement for traditional vertically mounted, single beam systems. Many of these principles are also applicable to multiple transducer sweep systems and multibeam systems. This chapter especially focuses on the critical calibrations required to maintain quality control in single beam echo sounding equipment. These criteria are summarized in Table 9-6 at the end of this chapter. 9-2. Principles of Acoustic Depth Measurement Reference water surface Transducer Outgoing signal VVeeloclocityty Transmitted and returned acoustic pulse Time Velocity X Time Draft d M e a s ure 2d depth is function of: Indexndex D • pulse travel time (t) • pulse velocity in water (v) D = 1/2 * v * t Reflected signal Figure 9-1. Acoustic depth measurement 9-1 EM 1110-2-1003 1 Jan 02 a. -

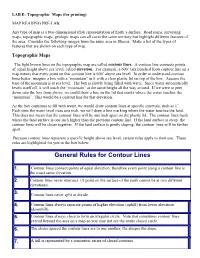

General Rules for Contour Lines

6/30/2015 EASC111LabEFor Printing LAB E: Topographic Maps (for printing) MAP READING PRELAB: Any type of map is a twodimensional (flat) representation of Earth’s surface. Road maps, surveying maps, topographic maps, geologic maps can all cover the same territory but highlight different features of the area. Consider the following images from the same area in Illinois. Make a list of the types of features that are shown on each type of map. Topographic Maps The light brown lines on the topographic map are called contour lines. A contour line connects points of equal height above sea level, called elevation. For example, a 600’ (six hundred foot) contour line on a map means that every point on that contour line is 600’ above sea level. In order to understand contour lines better, imagine a box with a “mountain” in it with a clear plastic lid on top of the box. Assume the base of the mountain is at sea level. The box is slowly being filled with water. Since water automatically levels itself off, it will touch the “mountain” at the same height all the way around. If we were to peer down into the box from above, we could draw a line on the lid that marks where the water touches the “mountain”. This would be a contour line for that elevation. As the box continues to fill with water, we would draw contour lines at specific intervals, such as 1”. Each time the water level rises one inch, we will draw a line marking where the water touches the land. -

Maps and Charts

Name:______________________________________ Maps and Charts Lab He had bought a large map representing the sea, without the least vestige of land And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be, a map they could all understand - Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark Map Projections: All maps and charts produce some degree of distortion when transferring the Earth's spherical surface to a flat piece of paper or computer screen. The ways that we deal with this distortion give us various types of map projections. Depending on the type of projection used, there may be distortion of distance, direction, shape and/or area. One type of projection may distort distances but correctly maintain directions, whereas another type may distort shape but maintain correct area. The type of information we need from a map determines which type of projection we might use. Below are two common projections among the many that exist. Can you tell what sort of distortion occurs with each projection? 1 Map Locations The latitude-longitude system is the standard system that we use to locate places on the Earth’s surface. The system uses a grid of intersecting east-west (latitude) and north-south (longitude) lines. Any point on Earth can be identified by the intersection of a line of latitude and a line of longitude. Lines of latitude: • also called “parallels” • equator = 0° latitude • increase N and S of the equator • range 0° to 90°N or 90°S Lines of longitude: • also called “meridians” • Prime Meridian = 0° longitude • increase E and W of the P.M.