Baroque Architecture Definition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aynemateriality, Crafting, and Scale in Renaissance

Materiality, Crafting, and Scale in Renaissancealin Architecture a ayne Alina Payne Materiality, Crafting, and Scale in Renaissance Architecture1 Alina Payne 1. This article draws from a series of lectures given at the INHA and EPHE, Paris in June 2008 and will form a part of my upcoming book on the Materiality of Architecture in the Renaissance.Iam On the whole twentieth-century Renaissance architectural scholarship has paid grateful to Sabine Frommel who first gave me the little attention to architecture’s dialogue with the other arts, in particular with opportunity to address this material by inviting 2 me to Paris, and to Maria Loh and Patricia Rubin sculpture and the so-called minor arts. The fact that architects were also for inviting me to develop this argument further. painters, sculptors, decorators, and designers of festivals and entries, as well I am also grateful to David Kim, Maria Loh, and as makers of a multitude of objects from luxury items to machines, clocks, the anonymous reviewers who offered very useful measuring and lifting instruments, in many different materials has also comments to an earlier draft. dropped out of attention. Indeed, broadly involved in the world of objects – 2. Among the last publications to take a holistic large and small, painted or drawn, carved or poured – architects were view of Renaissance architecture was Julius Baum, Baukunst und dekorative Plastik der fru¨heren highly conversant with a variety of artistic media that raise the question as to Renaissance in Italien (J. Hoffman: Stuttgart, what these experiences contributed to the making of buildings. For example, 1926). -

Michelangelo's Locations

1 3 4 He also adds the central balcony and the pope’s Michelangelo modifies the facades of Palazzo dei The project was completed by Tiberio Calcagni Cupola and Basilica di San Pietro Cappella Sistina Cappella Paolina crest, surmounted by the keys and tiara, on the Conservatori by adding a portico, and Palazzo and Giacomo Della Porta. The brothers Piazza San Pietro Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano Musei Vaticani, Città del Vaticano facade. Michelangelo also plans a bridge across Senatorio with a staircase leading straight to the Guido Ascanio and Alessandro Sforza, who the Tiber that connects the Palace with villa Chigi first floor. He then builds Palazzo Nuovo giving commissioned the work, are buried in the two The long lasting works to build Saint Peter’s Basilica The chapel, dedicated to the Assumption, was Few steps from the Sistine Chapel, in the heart of (Farnesina). The work was never completed due a slightly trapezoidal shape to the square and big side niches of the chapel. Its elliptical-shaped as we know it today, started at the beginning of built on the upper floor of a fortified area of the Apostolic Palaces, is the Chapel of Saints Peter to the high costs, only a first part remains, known plans the marble basement in the middle of it, space with its sail vaults and its domes supported the XVI century, at the behest of Julius II, whose Vatican Apostolic Palace, under pope Sixtus and Paul also known as Pauline Chapel, which is as Arco dei Farnesi, along the beautiful Via Giulia. -

The Architectural Style of Bay Pines VAMC

The Architectural Style of Bay Pines VAMC Lauren Webb July 2011 The architectural style of the original buildings at Bay Pines VA Medical Center is most often described as “Mediterranean Revival,” “Neo-Baroque,” or—somewhat rarely—“Churrigueresque.” However, with the shortage of similar buildings in the surrounding area and the chronological distance between the facility’s 1933 construction and Baroque’s popularity in the 17th and 18th centuries, it is often wondered how such a style came to be chosen for Bay Pines. This paper is an attempt to first, briefly explain the Baroque and Churrigueresque styles in Spain and Spanish America, second, outline the renewal of Spanish-inspired architecture in North American during the early 20th century, and finally, indicate some of the characteristics in the original buildings which mark Bay Pines as a Spanish Baroque- inspired building. The Spanish Baroque and Churrigueresque The Baroque style can be succinctly defined as “a style of artistic expression prevalent especially in the 17th century that is marked by use of complex forms, bold ornamentation, and the juxtaposition of contrasting elements.” But the beauty of these contrasting elements can be traced over centuries, particularly for the Spanish Baroque, through the evolution of design and the input of various cultures living in and interacting with Spain over that time. Much of the ornamentation of the Spanish Baroque can be traced as far back as the twelfth century, when Moorish and Arabesque design dominated the architectural scene, often referred to as the Mudéjar style. During the time of relative peace between Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Spain— the Convivencia—these Arabic designs were incorporated into synagogues and cathedrals, along with mosques. -

Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde

87T" ACSA ANNUAL MEETING 125 Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde ELIZABETH C. ENGLISH University of Pennsylvania THE CONTEXT OF THE DEBATES BETWEEN Gogol and Nikolai Nadezhdin looked for ways for architecture to THE WESTERNIZERS AND THE SLAVOPHILES achieve unity out of diverse elements, such that it expressed the character of the nation and the spirit of its people (nnrodnost'). In the teaching of Modernism in architecture schools in the West, the Theories of art became inseparably linked to the hotly-debated historical canon has tended to ignore the influence ofprerevolutionary socio-political issues of nationalism, ethnicity and class in Russia. Russian culture on Soviet avant-garde architecture in favor of a "The history of any nation's architecture is tied in the closest manner heroic-reductionist perspective which attributes Russian theories to to the history of their own philosophy," wrote Mikhail Bykovskii, the reworking of western European precedents. In their written and Nikolai Dmitriev propounded Russia's equivalent of Laugier's manifestos, didn't the avantgarde artists and architects acknowledge primitive hut theory based on the izba, the Russian peasant's log hut. the influence of Italian Futurism and French Cubism? Imbued with Such writers as Apollinari Krasovskii, Pave1 Salmanovich and "revolutionary" fervor, hadn't they publicly rejected both the bour- Nikolai Sultanov called for "the transformation. of the useful into geois values of their predecessors and their own bourgeois pasts? the beautiful" in ways which could serve as a vehicle for social Until recently, such writings have beenacceptedlargelyat face value progress as well as satisfy a society's "spiritual requirements".' by Western architectural historians and theorists. -

Renaissance Architecture History of Architecture

Renaissance Architecture History of Architecture No’man Bayaty Introduction • The Renaissance movement was a grand scale movement in art, literature sculpture and architecture. • The time in which it spread between 15th century and 17th century, was a time of movement in philosophy, science and other ideas. • At this time Europe was made of many small states united or trying to get united under larger kingdoms. • The Italian cities were independent, each with its special culture. • The Holy Roman Empire was quite weak, and the so were the Popes. • Local cultures were rising, so were local national states. • Europe lost Constantinople in 1453 A. D. but got all of Spain back. Introduction • Scientific achievements were getting more realistic, getting away from the mystical and superstitious ideas of the medieval ages. • The Christian reformation led by Martin Luther in 1517 A.D. added more division to the already divided Europe. • Galileo (1564 – 1642 A. D.) proved the earth was not the center of the universe, but a small dot in a grand solar system. • Three inventions had a great influence, gunpowder, printing and the marine compass. Introduction Introduction • Renaissance started in Italy. • The Gothic architecture never got a firm hold in Italy. • Many things aided the Italians to start the Renaissance, the resentment to Gothic, the discovery of new classical ruins and the presence of great Roman structures. • The movement in art and sculpture started a century before architecture. • The movement was not a gradual development from the Gothic, like the Gothic did from Romanesque, but was a bit more sudden and more like a conscious choice by artists and architects. -

1 Dataset Illustration

1 Dataset Illustration The images are crawled from Wikimedia. Here we summary the names, index- ing pages and typical images for the 66-class architectural style dataset. Table 1: Summarization of the architectural style dataset. Url stands for the indexing page on Wikimedia. Name Typical images Achaemenid architecture American Foursquare architecture American craftsman style Ancient Egyptian architecture Art Deco architecture Art Nouveau architecture Baroque architecture Bauhaus architecture 1 Name Typical images Beaux-Arts architecture Byzantine architecture Chicago school architecture Colonial architecture Deconstructivism Edwardian architecture Georgian architecture Gothic architecture Greek Revival architecture International style Novelty 2 architecture Name Typical images Palladian architecture Postmodern architecture Queen Anne architecture Romanesque architecture Russian Revival architecture Tudor Revival architecture 2 Task Description 1. 10-class dataset. The ten datasets used in the classification tasks are American craftsman style, Baroque architecture, Chicago school architecture, Colonial architecture, Georgian architecture, Gothic architecture, Greek Revival architecture, Queen Anne architecture, Romanesque architecture and Russian Revival architecture. These styles have lower intra-class vari- ance and the images are mainly captured in frontal view. 2. 25-class dataset. Except for the ten datasets listed above, the other fifteen styles are Achaemenid architecture, American Foursquare architecture, Ancient Egyptian architecture, -

Romanesque Renaissance – Introduction

Romanesque Renaissance – Introduction Konrad Ottenheym ‘Look at this majestic building with all its columns, and now you can imagine how many slaves these Roman emperors must have used to build it!’, I heard a tourist guide explaining to his group on the Piazza Venezia in Rome in 2016, as he pointed to the imposing marble monument to Vittorio Emanuele II. The Altare della Patria, symbol of the unified Italian kingdom of the nineteenth cen- tury, is in fact barely a century old, having been built in 1895–1911.1 Apparently, even in our time it is not always easy to make out the refined differences be- tween genuine ancient Roman architecture and later works of art which were meant to create a visual connection with the glorious past. Erroneous dating of old buildings, interpreting them as far older than they actually are, has hap- pened in all centuries. From the fifteenth century onwards, antiquarians, humanist scholars, ar- chitects and artists, striving for a revival of the architectural forms and prin- ciples of Ancient Rome, investigated respectable ruins and age-old buildings in order to look for useful models and sources of inspiration. They too, oc- casionally misinterpreted younger buildings as proofs of majestic Roman or other ancient glory. This especially was assumed for buildings that were con- sciously inspired by ancient Roman architecture, such as the buildings of the Carolingian, Ottonian and Stauffer emperors. But even if the correct age of a certain building was known (Charlemagne’s Palatine Chapel in Aachen, for example), buildings from c. 800–1200 were sometimes regarded as ‘Antique’ architecture, since the concept of ‘Antiquity’ was far more stretched than our modern periodisation allows. -

Th E a G a K H a N P Ro G R a M F O R Is La M Ic a R C H

THE AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE 8issue AKPIA AKTC Established in 1979, the Aga Khan Pro- Buildings and public spaces are grams for Islamic Architecture (AKPIA) at physical manifestations of culture in Harvard University and at the Massa- societies both past and present. They chusetts Institute of Technology are sup- represent human endeavors that can ported by endowments for instruction, enhance the quality of life, foster self- akpia research, and student aid from His High- understanding and community values, THE AGA KHANTRUST FOR CULTURE ness the Aga Khan. AKPIA is dedicated to and expand opportunities for economic aktc the study of Islamic architecture, urban- and social development into the 2 0 1 1 - 2 0 1 2 ism, visual culture, and conservation, in future. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture an effort to respond to the cultural and (AKTC) is an integral part of the Aga features: educational needs of a diverse constitu- Khan Development Network (AKDN), Harvard HAA ency drawn from all over the world. a family of institutions created by His Activities p. 2 Highness the Aga Khan with distinct yet People p. 8 Along with the focus on improving the complementary mandates to improve teaching of Islamic art and architecture the welfare and prospects of people Harvard GSD Activities p. 20 and setting a standard of excellence in in countries of the developing world, People p. 27 professional research, AKPIA also con- particularly in Asia and Africa. tinually strives to promote visibility of MIT Activities p. 33 the pan-Islamic cultural heritage. Though their spheres of activity and People p. -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Old San Juan

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD SAN JUAN HISTORIC DISTRICT/DISTRITO HISTÓRICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Old San Juan Historic District/Distrito Histórico del Viejo San Juan Other Name/Site Number: Ciudad del Puerto Rico; San Juan de Puerto Rico; Viejo San Juan; Old San Juan; Ciudad Capital; Zona Histórica de San Juan; Casco Histórico de San Juan; Antiguo San Juan; San Juan Historic Zone 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Western corner of San Juan Islet. Roughly bounded by Not for publication: Calle de Norzagaray, Avenidas Muñoz Rivera and Ponce de León, Paseo de Covadonga and Calles J. A. Corretejer, Nilita Vientos Gastón, Recinto Sur, Calle de la Tanca and del Comercio. City/Town: San Juan Vicinity: State: Puerto Rico County: San Juan Code: 127 Zip Code: 00901 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: X District: _X_ Public-State: X_ Site: ___ Public-Federal: _X_ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 699 128 buildings 16 6 sites 39 0 structures 7 19 objects 798 119 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 772 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form ((Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 OLD SAN JUAN HISTORIC DISTRICT/DISTRITO HISTÓRICO DEL VIEJO SAN JUAN Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Plaaces Registration Form 4. -

725 Clare Robertson This Exceptional Book Focuses on and Around The

Book Reviews 725 Clare Robertson Rome 1600: The City and the Visual Arts Under Clement viii. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015. Pp. 460. Hb, $75. This exceptional book focuses on and around the Holy Year of 1600, declared by Pope Clement viii Aldobrandini (r.1592–1605), and explores the distinctive artistic patronage of a period when donors and artists in Rome must have felt “in the right place at the right time.” Robertson constructs a fascinating web of overlapping points of views: the visual—a systematic analysis of works of art commissioned by Pope Clement viii, his cardinal nephew Pietro, the prin- cipal religious orders, confraternities, cardinals, and nobles; the historical—a profound literary and archival investigation of the papacy, the Aldobrandini family, the lives of the artists, and the history of the city of Rome seen through different social lenses; and the topographical—an analysis of the urban trans- formations of the abitato and disabitato through maps and documents. This is a beautifully illustrated book divided into five chapters (“Clement viii and Al- dobrandini Patronage;” “The Cardinal Nephew, Pietro Aldobrandini;” “Palaces, Villas and Gardens;” “Churches and Chapels;” and “Lives of the Artists”) that draws upon exhaustive historical and archival research, ideally synthesized by one of the most distinguished scholars in the field. With her book on the Farnese family (“Il gran cardinale”: Alessandro Farnese, Patron of the Arts [New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992]), Robertson had mastered the patterns of patronage within the family of Pope Paul iii and, in particular, of the cardinal nephew Alessandro, with emphasis on Rome and the villa in Caprarola. -

Three Periods of English Architecture

MBMTRAND SMITHS BOOK STORE M# PACIFIC A VENUS LONG BEACH. CALTP. THREE PERIODS OF <$> ENGLISH ARCHITECTURE. IMPORTED BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS, NEW YORK. THREE PERIODS^ OF ENGLISH ARC HITECTURE BY THOMAS HARRIS F R I B A- FSANI«$> B-T-BATSFORDf LONDON f 1 894 CHISWICK PRESS : —CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON. PREFACE. the following pages much is advanced which may- INjustify the charge of lack of novelty. It is, however, the author's intention to be little more than " a gatherer and disposer of other men's stuff," his object being to advance the cause of architectural progress, not so much by enunciating his own views, as by showing how much has been said on the subject by others. This will explain the apparent abruptness of some of the quotations, they being, for the most part, introduced with little attempt at constructive arrangement, where they appeared to best elucidate the text, or to lend the authority of some well- known name to the proposition under consideration ; but they will be found to form a kind of thought mosaic, each one either helping to strengthen, or in some cases to tone down, the others with which it is connected. The progress herein alluded to has found many advo- cates at the Royal Institute of British Architects, and names of the highest repute are associated with it. Archi- tectural publications, both here and in America, have frequently given expression to the longing for relief from the bondage to which the profession has been so long subject, and from the delusions which have militated against the clear apprehension of the destiny of their art. -

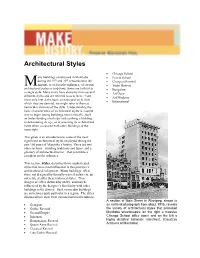

Architectural Style Guide.Pdf

Architectural Styles Chicago School any buildings constructed in Manitoba Prairie School th th during the 19 and 20 centuries bear the Georgian Revival M imprint, or at least the influence, of certain Tudor Revival architectural styles or traditions. Some are faithful to Bungalow a single style. Many more have elements from several Art Deco different styles and are referred to as eclectic. Even Art Moderne more only hint at the basic architectural style from International which they are derived; we might refer to them as vernacular versions of the style. Understanding the basic characteristics of architectural styles is a useful way to begin seeing buildings more critically. Such an understanding also helps in describing a building, in determining its age, or in assessing its architectural value when compared with other buildings of the same style. This guide is an introduction to some of the most significant architectural styles employed during the past 150 years of Manitoba’s history. There are two other sections—building traditions and types, and a glossary of architectural terms—that constitute a complete set for reference. This section, Styles, describes those sophisticated styles that were most influential in this province’s architectural development. Many buildings, often those not designed by formally-trained architects, do not relate at all to these historical styles. Their designs are often dictated by utility, and may be influenced by the designer’s familiarity with other buildings in the district. Such vernacular buildings are sometimes quite particular to a region. The styles discussed here stem from various historical traditions. A section of Main Street in Winnipeg, shown in Georgian an archival photograph from about 1915, reveals Gothic Revival the variety of architectural styles that animated Second Empire Manitoba streetscapes: on the right a massive Italianate Chicago School office tower and on the left a Romanesque Revival highly detailed Italianate storefront.