Mediterranean Historical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S.No Adi Soyadi Atama Sebebi Açiklama 1 Abdullah Azgin

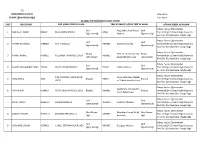

T.C KASTAMONU VALİLİĞİ Liste Tarihi: (İl Milli Eğitim Müdürlüğü) Liste Sayısı: ATAMA/YER DEĞİŞTİRME ONAY LİSTESİ S.NO ADI SOYADI ESKİ GÖREV YERİ VE ALANI YENİ ATANDIĞI GÖREV YERİ VE ALANI ATAMA SEBEBİ AÇIKLAMA İhtiyaç Fazlası Öğretmenler Sınıf Araç Şehit Ünsal Aksoy Sınıf 1 ABDULLAH AZGIN DADAY SELALMAZ İLKOKULU ARAÇ Yönetmeliğin 53.mad. Doğrultusunda Öğretmenliği İlkokulu Öğretmenliği 5442 SK. 8/c Mad.Göre İsteğe Bağlı İhtiyaç Fazlası Öğretmenler Sınıf Sınıf 2 AHMET ÇİFCİOĞLU MERKEZ KAYI İLKOKULU MERKEZ Darende İlkokulu Yönetmeliğin 53.mad. Doğrultusunda Öğretmenliği Öğretmenliği 5442 SK. 8/c Mad.Göre İsteğe Bağlı İhtiyaç Fazlası Öğretmenler Bilişim Prof. Dr. Saime İnal Savi Bilişim 3 AHMET MERAL MERKEZ KUZEYKENT ANADOLU LİSESİ MERKEZ Yönetmeliğin 53.mad. Doğrultusunda Teknolojileri Sosyal Bilimler Lisesi Teknolojileri 5442 SK. 8/c Mad.Göre İsteğe Bağlı İhtiyaç Fazlası Öğretmenler Sınıf Sınıf 4 AHMET MUHAMMET ORAK TOSYA YAVUZ SELİM İLKOKULU TOSYA Sekiler İlkokulu Yönetmeliğin 53.mad. Doğrultusunda Öğretmenliği Öğretmenliği 5442 SK. 8/c Mad.Göre İsteğe Bağlı İhtiyaç Fazlası Öğretmenler CİDE ANADOLU İMAM HATİP Hasan Rıza Paşa Mesleki 5 ARZU SOYLU CİDE Biyoloji TOSYA Biyoloji Yönetmeliğin 53.mad. Doğrultusunda LİSESİ ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi 5442 SK. 8/c Mad.Göre İsteğe Bağlı İhtiyaç Fazlası Öğretmenler Kastamonu Kız Anadolu 6 AYHAN SEKİ MERKEZ AYTAÇ ERUZ ANADOLU LİSESİ Biyoloji MERKEZ Biyoloji Yönetmeliğin 53.mad. Doğrultusunda İmam Hatip Lisesi 5442 SK. 8/c Mad.Göre İsteğe Bağlı İhtiyaç Fazlası Öğretmenler Sınıf Sınıf 7 AYKUT TÜRÜT İNEBOLU YUKARI İLKOKULU İNEBOLU 9 Haziran İlkokulu Yönetmeliğin 53.mad. Doğrultusunda Öğretmenliği Öğretmenliği 5442 SK. 8/c Mad.Göre İsteğe Bağlı İhtiyaç Fazlası Öğretmenler Okul Öncesi Vilayetler Hizmet Birliği Okul Öncesi 8 AYNUR GENÇERİ İNEBOLU ATATÜRK ORTAOKULU MERKEZ Yönetmeliğin 53.mad. -

Anadolu'da Moğol Istilasının Başlangıcı Ve Kadim Şehir Erzurum

ANADOLU’DA MOĞOL İSTİLASININ BAŞLANGICI VE KADİM ŞEHİR ERZURUM Dr. Öğr. Üyes Gonca SUTAY ANADOLU’DA MOĞOL İSTİLASININ BAŞLANGICI VE KADİM ŞEHİR ERZURUM Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Gonca SUTAY* * Iğdır Üniversitesi Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi Tarih Bölümü, e-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2020 by iksad publishing house All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. Institution of Economic Development and Social Researches Publications® (The Licence Number of Publicator: 2014/31220) TURKEY TR: +90 342 606 06 75 USA: +1 631 685 0 853 E mail: [email protected] www.iksad.net It is responsibility of the author to abide by the publishing ethics rules. Iksad Publications – 2020© ISBN: 978-625-7954-42-6 Cover Design: İbrahim KAYA February / 2020 Ankara / Turkey Size = 16 x 24 cm İÇİNDEKİLER ÖNSÖZ ...................................................................................................... 5 GİRİŞ......................................................................................................... 7 Şehrin Tarihi Coğrafyası ................................................................. 7 Tarih Boyunca Erzurum’a Verilen İsimler ...................................... 8 I. BÖLÜM ........................................................................................... -

Kastamonu İli Tabanidae (Insecta: Diptera) Faunası'na Katkılar1

Kastamonu Üni., Orman Fakültesi Dergisi, 2011, 11 (1): 1 - 8 Kastamonu Univ., Journal of Forestry Faculty Kastamonu İli Tabanidae (Insecta: Diptera) Faunası’na Katkılar 1 A.Yavuz KILIÇ, Ferhat ALTUNSOY Anadolu Üniversitesi, Fen Fakültesi, Biyoloji Bölümü, Eski şehir *Sorumlu Yazar: [email protected] Geli ş Tarihi: 23.03.2010 Özet Kastamonu Đli ve çevresinde 1999, 2000 ve 2001 yıllarında Tabanidae (Diptera) eğinlerinin aktivite dönemlerinde 35 tür tespit edilmi ştir. Bunlardan 32’si; Nemorius vitripennis (Meig. 1820), Chrysops caecutiens (L. 1761), C. flavipes Meig. 1804, Atylotus flavoguttatus, (Szi., 1915), A. loewianus (Vill., 1920), Tabanus armeniacus Kröb. 1928, T. autumnalis Lw. 1858, T. briani Lecl. 1962, T. bromius L. 1761, T. cordiger Meig. 1820, T. exclusus Pand. 1883, T. fraseri Aus. 1925, T. glaucopis, Meig. 1936, T. leleani Aus. 1920, T. lunatus Fab. 1794, T. maculicornis Zett., 1842, T. miki Brauer 1880, T. oppugnator Aust. 1925, T. portschinskii Ols. 1937, T. regularis Jaenn., 1866, T. rupium Brauer 1880, T. spodopterus Meig. 1820, T. tergestinus Egg. 1859 , T. tinctus Walk. 1850, T. unifasciatus Lw. 1858, Haematopota grandis Macq. 1834, H. italica Meig. 1804, H. longantennata Ols. 1937, H. ocelligera Kröb. 1922, H. pandazisi (Kröb., 1936), H. pluvialis (L., 1761) ve H. subcylindrica Pand. 1883, il çevresinden ilk kez bildirilmektedir. Anahtar Kelimeler : Tabanidae, Diptera, Fauna, Kastamonu, Türkiye Contribution to Tabanidae (Insecta:Diptera) Fauna of Kastamonu Province Abstract In this study, 35 Tabanidae species were determinated in adult activity period in the years 1999, 2000 and 2001 in Kastamonu province. These are Nemorius vitripennis (Meig. 1820), Chrysops caecutiens (L. 1761), C. flavipes Meig. 1804, Atylotus flavoguttatus, (Szi., 1915), A. -

Michael Panaretos in Context

DOI 10.1515/bz-2019-0007 BZ 2019; 112(3): 899–934 Scott Kennedy Michael Panaretos in context A historiographical study of the chronicle On the emperors of Trebizond Abstract: It has often been said it would be impossible to write the history of the empire of Trebizond (1204–1461) without the terse and often frustratingly la- conic chronicle of the Grand Komnenoi by the protonotarios of Alexios III (1349–1390), Michael Panaretos. While recent scholarship has infinitely en- hanced our knowledge of the world in which Panaretos lived, it has been approx- imately seventy years since a scholar dedicated a historiographical study to the text. This study examines the world that Panaretos wanted posterity to see, ex- amining how his post as imperial secretary and his use of sources shaped his representation of reality, whether that reality was Trebizond’s experience of for- eigners, the reign of Alexios III, or a narrative that showed the superiority of Tre- bizond on the international stage. Finally by scrutinizing Panaretos in this way, this paper also illuminates how modern historians of Trebizond have been led astray by the chronicler, unaware of Panaretos selected material for inclusion for the narratives of his chronicle. Adresse: Dr. Scott Kennedy, Bilkent University, Main Camous, G Building, 24/g, 06800 Bilkent–Ankara, Turkey; [email protected] Established just before the fall of Constantinople in 1204, the empire of Trebi- zond (1204–1461) emerged as a successor state to the Byzantine empire, ulti- mately outlasting its other Byzantine rivals until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1461. -

| | | | | | Naslefardanews Naslfarda

واد اتاد ور هان صبا با م ﺟﻨ ﺳﺎ ﺑﺪﺑﯿﻨﻰ ﺮ ﻪ ﺑﺎ و ﺑﺎ ﮔﺖ ﻣﺸ ﻣﯿﺪان اﻣﺎ ﻠ ﻰ ﺗﺎ اواﯾ ﺳﺎل آﯾﻨﺪ ﯿﺰ را ﻧﺎﺑﻮد ﮐﺮد ﺗﺎﺷﺎﮔﺮى ﮐﻪ ﯾﺎر ﻮاﺪ ﺷﺪ دﯾﮕﺮ ﺗﺤﻤﻞ ﺑﺪﮔﻤﺎﻧﻰ ﻫﺎ و ﺳــﻮءﻇﻦ او ﻣﻨﻄﻘﻪ 3 ﺷــﻬﺮدارى اﺻﻔﻬﺎن ﯾﮑﻰ از را ﻧﺪارم و اﺻﻼ ﻓﮑﺮ ﻣﻰ ﮐﻨﻢ ﺑﺎ ﮐﺴﯽ ﮐﻪ دوازد ﻧﯿﺖ ﺳﻪ ﻣﻨﻄ ﻘﻪ ﺑﺎ ﺑﯿﺸﺘﺮﯾﻦ ﺑﺎﻓﺖ ﺗﺎرﯾﺨﻰ، ﺳﻮء ﻇﻦ داﺷﺘﻪ ﺑﺎﺷﺪ، ﻧﻤﻰ ﺷﻮد زﻧﺪﮔﯽ ﺷــﻬﺮآورد ﻓﻮﺗﺒﺎل اﺻﻔﻬﺎن در ﺣﺎﻟﻰ ﺑﺎ رﺳﺎﻧ ﻪﺎ ﻣﺎﺋ ﺗﻰ ﺑﺎﻓﺖ ﻓﺮﺳﻮده، ﮔﻠﻮﮔ ﺎهﻫﺎ و ﭘﺎرﮐﯿﻨﮓ ﻫﺎ ﮐﺮد؛ ﭼﻨﺎن ﻣﻬﺮ او از دﻟﻢ رﻓﺘﻪ اﺳﺖ ﮐﻪ ﺎد ﻣﺎﻟﻰ ﺮ ﻟﻨﮕﺎن ﺑﺮﺗﺮى ﺳــﭙﺎﻫﺎن ﺑﻪ ﭘﺎﯾﺎن رﺳﯿﺪ ﮐﻪ ﺑﻌﺪ در اﺻﻔﻬﺎن اﺳﺖ و ﻧﯿﺰ ﻣﺤﻞ داد و ﺳﺘﺪ در آﻣﻮزش و ﭘﺮورش را ﺑﻪ ﺣﺎﻟﺖ ﺗﻨﻔﺮ رﺳﯿﺪه ام ،ﭼﻮن ﻣﻦ ﻫﯿﭻ اﺎد در ﺷﻬﺮ از 11 ﺳﺎل ﺑﺎز ﻫﻢ اﺳﺘﺎدﯾﻮم ﻧﻘ ﺶﺟﻬﺎن ﺗﺠﺎرى ﺑﺮاى 350 اﻟﻰ 400 ﻫﺰار ﻧﻔﺮ در راﺑﻄﻪاى ﺑﺎ ﻣﺮد دﯾﮕﺮى... 14 15 ﻣﯿﺰﺑﺎن رﻗﺎﺑﺖ دو ﺗﯿﻢ اﺻﻔﻬﺎﻧﻰ... 18 ﺮاﻣﻮش ﮐﺮد اﻧﺪ 14 ﻃﻰ روز اﺳﺖ... 16 ﭼﻬﺎرﺷﻨﺒﻪ| 18 اﺳﻔﻨﺪ 1395| 8 ﻣﺎرس 2017 | 9 ﺟﻤﺎدى اﻟﺜﺎﻧﻰ 1438 | ﺳﺎل ﺑﯿﺴﺖ و ﺷﺸﻢ| ﺷﻤﺎره 5356| ﺻﻔﺤﻪ WWW. NASLEFARDA.NET naslefardanews naslfarda 30007232 13 ﯾﺎاﺷﺖ ی ﺮ روزﻣﺎن ﻧﻮروز عی مهی در اصفهان ف ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎد اﻣﺮوز اﻣﯿﺮﺣﺴﯿﻦ ﭼﯿ ﺖﺳﺎززاده دم دﻣــﺎى ﻋﯿﺪ ﻧﻮروز ﮐﻪ ﻣﯿﺸــﻪ ﻋﺎم و ﺧﺎ ﯾﺎدﺷﻮن ﻣﯿﺎد ﺑﻪ ﺗﯿﯿﺮ و ﺗﺤﻮل دﺳﺖ ﺑﺰﻧﻦ؛ ﺣﺎﻻ از ﻣﺪﯾﺮﯾﺖ ﯾﮏ ﻓﻌﺎﻟﯿﺖ اﻗﺘﺼﺎدى ﺑﺎ اﺷــﮑﺎﻟﻰ ﻫﻤﭽﻮن ﻧﻮ ﻧﻮار ﮐــﺮدن ﻣﺤﺼﻮﻻت و ﺧﺪﻣﺎت اراﺋﻪ ﺷــﺪه و رﺳــﯿﺪﮔﻰ ﺑﻪ اﻣﻮر ﻣﺸﺘﺮﯾﺎن و ﯿﻠﺮ ﯾﻨ ﯾﻨﻰ دﮐﻮرﻫﺎى ﺟﺪﯾﺪﺗــﺮ و... ﮔﺮﻓﺘﻪ ﺗــﺎ ﻣﺪﯾﺮان و ﺧﺎدﻣﯿﻦ ﻣﺮدم ﮐﻪ ﺑﻪ ﯾﺎد رﺳــﯿﺪﮔﻰ ﺑﻪ ﻇﻮاﻫﺮ ﺷــﻬﺮى و آﻣﺎرى ﻣﻰاﻓﺘﻦ. -

1. Mekânsal Gelişme

1. Mekânsal Gelişme Plan dönemi sonu olan 2023 yılına kadar Bölgenin ciddi yapısal dönüşümler yaşayacağı ve gelişme eksenlerinin farklı yönlere kayacağı öngörülmektedir. Hâlihazırda ağırlıklı olarak il merkezleri, Tosya, Boyabat ve Şabanözü gibi endüstriyel olarak gelişmiş ilçeler etrafında şekillenen sosyoekonomik yapı (Bkz. Harita 1) yerini 2023 yılında daha dengeli bir kademelenmeye bırakacaktır (Bkz. Harita 2). Sektörel kademelenmede mevcut durum niceliksel ve niteliksel analizlere dayanmaktadır. İlçelerin ilgili sektörlerindeki bölgesel durumu mevcut veriler ile analiz edilerek; saha çalışmaları, yüz yüze görüşmeler ve anketler yoluyla elde edilen bilgiler ile sentezlenmiştir. Bu sentez sonucunda mevcut kademelenme oluşturulmuş olup; 2023 sektörel kademelenmesi ise bölgesel politikalar doğrultusunda planlanan kademeleri göstermektedir. Bölgesel politikaların etkin biçimde uygulanmasıyla birlikte Bölgedeki tüm yerleşmeler gelişecek ve bazı yerleşmelerin gelişme hızı bölgesel ortalamanın üzerinde seyrederek bölge içi gelişmişlik farklarını azaltıcı etki yaratacaktır. Bu durum il merkezleri üzerinde ekolojik baskıyı azaltacak hem bölge içi hem de bölgeler arası fonksiyonel ilişkiler artacaktır. Harita 1: Sektörel Kademelenme 2013 TR82 Bölgesi Kastamonu | Çankırı | Sinop www.kuzka.gov.tr Harita 2: Sektörel Kademelenme 2023 Özellikle ulaşım alanında devam eden büyük ölçekli yatırımlarının tamamlanması ile birlikte Bölgede 4 farklı kademede merkezler oluşacağı öngörülmektedir. İl merkezleri birincil konumlarını korurken Tosya, İnebolu, Boyabat, Gerze, Ayancık ve Kurşunlu – Çerkeş merkezli bölgeler ikinci kademede olacaklar ve birinci kademe merkezlere yakınsayacaklardır. İl merkezleri önemli birer hizmet merkezi olarak gelişecek ve çevre illerin sağladığı birçok kaliteli hizmeti sağlar konuma geleceklerdir. Kastamonu Merkez, sanayi, hayvancılık, üniversite, turizm ve diğer hizmet sektörleri ile büyürken, Sinop Merkez’de lider sektörler eğitim ve turizm olacaktır. Çankırı Merkez ise hem tarımsal üretim hem de sınai üretimde önemli bir merkez haline gelecektir. -

Jnasci-2015-1195-1202

Journal of Novel Applied Sciences Available online at www.jnasci.org ©2015 JNAS Journal-2015-4-11/1195-1202 ISSN 2322-5149 ©2015 JNAS Relationships between Timurid Empire and Qara Qoyunlu & Aq Qoyunlu Turkmens Jamshid Norouzi1 and Wirya Azizi2* 1- Assistant Professor of History Department of Payame Noor University 2- M.A of Iran’s Islamic Era History of Payame Noor University Corresponding author: Wirya Azizi ABSTRACT: Following Abu Saeed Ilkhan’s death (from Mongol Empire), for half a century, Iranian lands were reigned by local rules. Finally, lately in the 8th century, Amir Timur thrived from Transoxiana in northeastern Iran, and gradually made obedient Iran and surrounding countries. However, in the Northwest of Iran, Turkmen tribes reigned but during the Timurid raids they had returned to obedience, and just as withdrawal of the Timurid troops, they were quickly back their former power. These clans and tribes sometimes were troublesome to the Ottoman Empires and Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Due to the remoteness of these regions of Timurid Capital and, more importantly, lack of permanent government administrations and organizations of the Timurid capital, following Amir Timur’s death, because of dynastic struggles among his Sons and Grandsons, the Turkmens under these conditions were increasing their power and then they had challenged the Timurid princes. The most important goals of this study has focused on investigation of their relationships and struggles. How and why Timurid Empire has begun to combat against Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu Turkmens; what were the reasons for the failure of the Timurid deal with them, these are the questions that we try to find the answers in our study. -

Şenpazar İlçe Analizi 1.735 KB / .Pdf

T.C. KUZEY ANADOLU KALKINMA AJANSI ŞENPAZAR İLÇE ANALİZİ HAZIRLAYAN EMİNE MERVE KESER Planlama, Programlama ve Stratejik Araştırmalar Birimi Uzman Temmuz, 2013 i i Yönetici Özeti 2014 – 2018 Bölge Planına altlık teşkil edecek olan ilçe analizleri, Kuzey Anadolu Kalkınma Ajansı Planlama, Programlama ve Stratejik Araştırmalar Birimi tarafından 2012 yılında hazırlanmıştır. Kuzey Anadolu Kalkınma Ajansı’nın sorumluluk alanına giren TR82 Düzey 2 Bölgesi; Kastamonu, Çankırı ve Sinop illerinden müteşekkil olup, illerde sırasıyla (merkez ilçeler dâhil) 20, 12 ve 9 ilçe olmak üzere toplam 41 ilçe bulunmaktadır. Her bir ilçenin sosyal, ekonomik, kültürel ve mekansal olarak incelendiği ilçe analizleri, mikro düzeyli raporlardır. Analizin ilk 5 bölümü ilçedeki mevcut durumu yansıtmaktadır. Mevcut durum analizinden sonra ilgili ilçede düzenlenen “İlçe Odak Grup Toplantıları”yla, ampirik bulgular, ilçenin ileri gelen yöneticileri, iş adamları ve yerel inisiyatifleriyle tartışılarak analizin 6. Bölümünde bulunan ilçe stratejileri oluşturulmuştur. İlçe analizleri; İl Müdürlükleri, Kaymakamlıklar, Üniversiteler, Ticaret ve Sanayi Odaları, Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu ve Defterdarlıklardan alınan verilerle oluşturulduğundan, ilçeleri tanıtmanın yanında yatırımcılar için de aslında birer «Yatırım Ortamı Kılavuzu» olma özelliğini taşımaktadır. Şenpazar, Kastamonu ilinin kuzeybatısında, Karadeniz Bölgesi'nin Batı Karadeniz bölümünde yer almaktadır. Kastamonu il merkezine 100 km mesafede olup, Karadeniz'e uzaklığı 37 km’dir. İlçe Kuzeyde Cide, Güneyde Azdavay, Kuzeydoğuda Doğanyurt ilçeleri tarafından çevrilmiştir. Şenpazar, 1954 yılında nahiye olmuş, 1974 yılında Belediye teşkilatı kurulmuş olup; 1987 yılının Mayıs ayında ise ilçe olmasına karar verilmiştir. 1990 yılı nüfus sayımında 8.950 (2.887 Şehir - 6.063 Köy) olarak belirlenen ilçe nüfusu yıllar içerisinde her geçen sene göç vererek 2011 ADNKS verilerine göre 5.148’e ulaşmıştır. İlçe nüfusunun %31,55’i merkezde yaşarken, %68,45’i köylerde yaşamaktadır. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

Kastamonu İstatistiki Bölge Birimleri Sınıflandırılmasına (İBBS) Göre Türkiye, 26 Düzey-2 Bölgesine Ayrılmıştır

Kastamonu İstatistiki Bölge Birimleri Sınıflandırılmasına (İBBS) göre Türkiye, 26 düzey-2 bölgesine ayrılmıştır. TR82 Bölgesi Kastamonu, Çankırı ve Sinop’tan oluşmaktadır. Harita 1: Düzey 2 Bölgeleri İdari Yapı ve İlçeler Merkez, Abana, Ağlı, Araç, Azdavay, Bozkurt, Cide, Çatalzeytin, Daday, Devrekâni, Doğanyurt, Hanönü, İhsangazi, İnebolu, Küre, Pınarbaşı, Seydiler, Şenpazar, Tosya ve Taşköprü olmak üzere Kastamonu’da 20 ilçe bulunmaktadır. Kastamonu’da 2012 yılı verilerine göre 1.070 tane köy bulunmaktadır. Köylerin çoğu orman köyüdür. Kastamonu, Sivas ve Şanlıurfa’dan sonra Türkiye’de en fazla köye sahip üçüncü il konumundadır. Coğrafi Yapı Kastamonu İli Batı Karadeniz ve Kızılırmak Havzaları arasında yer almaktadır. Karadeniz sahiline paralel olarak il merkezinin kuzeyinde Küre (İsfendiyar) Dağları, ilin güneyinde ise yine doğu batı uzantılı Ilgaz Dağları bulunur. 13.152 km² yüzölçümüne sahip olan il Türkiye yüzölçümünün yaklaşık %1,7’sini oluşturmaktadır. İlin Karadeniz kıyı şeridi uzunluğu 170 km ve denizden yüksekliği 780 metre olup; dağlar denize paralel uzanmaktadır. Bu yüzden kıyılarda Karadeniz iklimi görülürken iç kısımlarda karasal iklim özellikleri görülmektedir. Kastamonu İli çoğunlukla engebeli arazilerden oluşmaktadır. %61,5 oranında ormanlarla kaplı olan İlin topraklarının büyük bölümü tarıma elverişli değildir. Ancak vadiler etrafında küçük ovalar göze çarpar. Bunlardan önemlileri Daday ve Taşköprü ovalarını içine alan Gökırmak ile Tosya tarım alanını kapsayan Devrez Vadileridir. Ayrıca Araç, Cide ve Devrekâni çay yatakları çevresinde de ekim ve dikime elverişli alanlar bulunmaktadır. İlde Ilgaz Dağı ve Küre Dağları Milli Parkı olmak üzere 2 önemli milli park mevcuttur. Ayrıca yaban hayatı geliştirme sahaları ve tabiat parkları bulunmaktadır. www.kuzka.gov.tr Kastamonu, Türkiye’nin en aktif fayı olan Kuzey Anadolu Fay Hattı üzerinde bulunmaktadır. -

Du Pont À La Macédoine : Les Grands Monastères Grecs Pontiques Marqueurs Territoriaux D'un Peuple En Diaspora

Le territoire, lien ou frontière ? Paris, 2-4 octobre 1995 Du Pont à la Macédoine : les grands monastères grecs pontiques marqueurs territoriaux d'un peuple en diaspora Michel BRUNEAU TIDE-CNRS, Bordeaux Les Grecs pontiques constituent au sein de la nation grecque un peuple distinct caractérisé par une identité forte mais non antagonique par rapport à l'identité nationale grecque. A la différence des Crétois ou des Epirotes, par exemple, qui ont aussi leur propre identité ethno- régionale, ils ne vivent pas sur leur territoire d'origine situé en Turquie, mais en diaspora. Au nombre d'environ 800 000 en Grèce, ils se sont installés en Macédoine-Thrace dans des villages ainsi que dans quelques quartiers et banlieues des agglomérations d'Athènes et de Thessalonique. Trente ans après leur installation, qui date de l'échange des populations de 1922- 23, ils ont entrepris la construction en Macédoine de sanctuaires rappelant les grands monastères qui, dans le Pont, leur avaient permis de préserver leur religion, leur langue et leur identité pendant quatre siècles de domination turque. Ces monastères, aujourd'hui au nombre de quatre, sont devenus les points focaux de leur affirmation identitaire qui se manifeste à travers leur iconographie (au sens de J. Gottmann, 1966) tant sur les monuments eux-mêmes que dans les cérémonies et pèlerinages annuels. Avant d'étudier les raisons et les modalités de leur reconstruction en Grèce, il faut comprendre comment et pourquoi ces monastères ont joué dans le territoire d'origine, dans le Pont, un rôle central pour la préservation de cette identité grecque. Les grands monastères du Pont, hauts lieux de l'hellénisme La fondation de ces monastères remonte à la christianisation de l'Asie Mineure, à l'ère byzantine. -

History of India

HISTORY OF INDIA VOLUME - 5 The Lake of Udaipur History of India Edited by A. V. Williams Jackson, Ph.D., LL.D., Professor of Indo-Iranian Languages in Columbia University Volume 5 – The Mohammedan Period as Described by its Own Historians Selected from the works of the late Sir Henry Miers Elliot, K.C.B. 1907 Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2018) Introduction by the Editor This volume, consisting of selections from Sir Henry M. Elliot’s great work on the history of Mohammedan India as told by its own historians, may be regarded as a new contribution, in a way, because it presents the subject from that standpoint in a far more concise form than was possible in the original series of translations from Oriental chroniclers, and it keeps in view at the same time the two volumes of Professor Lane- Poole immediately preceding it in the present series. Tributes to the value of Elliot’s monumental work are many, but one of the best estimates of its worth was given by Lane-Poole himself, from whom the following paragraph is, in part, a quotation. “To realize Medieval India there is no better way than to dive into the eight volumes of the priceless History of India as told by its own Historians, which Sir H. M. Elliot conceived and began, and which Professor Dowson edited and completed with infinite labor and learning. It is a revelation of Indian life as seen through the eyes of the Persian court analysts. As a source it is invaluable, and no modern historian of India can afford to neglect it.