Cosmic Ventures of the Olmec Dwarf: an Analysis of the Dispersal and Transformation of Dwarf Imagery Within Olmec Iconography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elemental Motes by Charles Choi Illustration by Rob Alexamder Little Fires up the Imagination More Than a Vision of the Well

Fantastic Terrain: Elemental Motes By Charles Choi illustration by Rob Alexamder Little fires up the imagination more than a vision of the well. The awe-inspiring heights that motes often soar at carry impossible, such as an island defying gravity by floating miles the promise of death-defying acts of derring-do that can stick high up in the air. This might be why castles in the sky are so with players for years. Although the constant risk of a poten- common in fantasy, from the ethereal cloud kingdoms seen tially lethal fall underlies the greatest strength of motes as a in fairy tales such as Jack and the Beanstalk to the ominous storytelling tool—spine-tingling suspense—unfortunately, it is flying citadels of Krynn in Dragonlance. also their greatest weakness. One wrong step on the part of either Dungeon Master or player, and a player character or Islands in the sky made their debut in 4th Edition as valuable nonplayer character can inadvertently go hurtling earthmotes in the updated Forgotten Realms® setting, and into the brink. However, such challenges can be overcome now they can be unforgettable elements in your campaign as easily with a little forethought. TM & © 2009 Wizards of the Coast LLC All rights reserved. March 2010 | Dungeon 176 76 Fantastic Terrain: Elemental Motes Motes in On the flipside, in settings where air travel is common, such as the Eberron® setting, motes Facts abouT Motes Your CaMpaign could become common ports of call. Such mote- Motes are often born from breaches between the ports can brim with adventure and serve as home mortal world and the Elemental Chaos, when matter In a game that includes monster-infested dungeons, to all kinds of intrigue. -

Meike Weijtmans S4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: Dr

Weijtmans, s4235797/1 Meike Weijtmans s4235797 BA Thesis English Language and Culture Supervisor: dr. Chris Cusack Examiner: dr. L.S. Chardonnens August 15, 2018 The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend M.A.S. Weijtmans BA Thesis August 15, 2018 Weijtmans, s4235797/2 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: dr. Chris Cusack, dr. L.S. Chardonnens Title of document: The Celtic Image in Contemporary Adaptations of the Arthurian Legend Name of course: BA Thesis Date of submission: August 15, 2018 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed Name of student: Meike Weijtmans Student number: s4235797 Weijtmans, s4235797/3 Abstract Celtic culture has always been a source of interest in contemporary popular culture, as it has been in the past; Greek and Roman writers painted the Celts as barbaric and uncivilised peoples, but were impressed with their religion and mythology. The Celtic revival period gave birth to the paradox that still defines the Celtic image to this day, namely that the rurality, simplicity and spirituality of the Celts was to be admired, but that they were uncivilised, irrational and wild at the same time. Recent debates surround the concepts of “Celt”, “Celticity” and “Celtic” are also discussed in this thesis. The first part of this thesis focuses on Celtic history and culture, as well as the complexities surrounding the terminology and the construction of the Celtic image over the centuries. This main body of the thesis analyses the way Celtic elements in contemporary adaptations of the Arthurian narrative form the modern Celtic image. -

Patinkas to Go with Our Beautiful Engraved Sets of Five Gemstone Elemental Stones©

.!Qbujolbt!.! This Fact Sheet has been created by Patinkas to go with our beautiful engraved sets of five gemstone Elemental Stones©. About Elementals An Elemental is a spirit of nature, embodying four of the five elements of Earth, Water, Air, and Fire. Ether does not have a specific elemental spirit associated with it. All of the five elements are combined in different proportions to make up the whole of creation and all are, therefore, present in us. The energetic essence of elementals is quite unique and unlike anything else in the intangible realms. It is said that they are responsible for creating, sustaining, and renewing all life on Earth. When we work with the five elements and Elemental spirits, we connect with their realms and associated energies, benefiting from these vibrations and balancing those elements within ourselves. Water Undines are the elemental of water; the spirits of the water world. They hail from the West and their Archangel is Gabriel. One of the earliest references goes back to ancient Greece and a clan of nymphs called Oceanides who dwelled in the waters of the world. Mythology says that they were the daughters of Titan and his wife Tethys. They were well known to sailors and sea farers as generally benign spirits who could be called on for safe passage in troubled waters or to aid in navigation. To cross one, however, was to be avoided at all costs, as their wrath could whip up a destructive tempest. In European folklore, Undines were said to be the itinerant spirits of bereft women; wounded through unrequited or lost love. -

Onimusha When One Shows Themselves a Potential Ally Against the Clan’S Enemies, the Oni Bestow Their Power on a Mortal Being to Aid Them in Fighting the Demon Hordes

Onimusha When one shows themselves a potential ally against the clan’s enemies, the Oni bestow their power on a mortal being to aid them in fighting the demon hordes. Granting them the Oni gauntlet, a power relic that lets one to master and use magical weapons to dispose of the clan’s enemies. The onimusha is an archetype of the samurai class. Limit Breaks (Su): At 1st level, the onimusha receives the Limit Breaks (Oni Trance and Oni Weapon Technique). Oni Trance (Su): This Limit Break allows the onimusha to enter a trance that increases his prowess in combat, taking on the appearance of an oni warrior of ancient times. His type changes to Outsider (Native) and gains Fast Healing 2 and a +2 dodge bonus to AC bonus. These bonuses increases by 2 per four samurai levels after 1st. Upon activating this limit break, he can summon forth a weapon from his dragon arsenal. This limit break lasts for a duration of 1 round + 1 round per four samurai levels after 1st. This limit break requires only a swift action. Oni Weapon Technique (Su): This Limit Break allows the onimusha to use a weapon from his dragon arsenal at its full potential using a new technique with the weapon. This limit break is a standard action to activate and is different depending on the wielded weapon. If he does not have a weapon summoned, he can as a free action without spending soul points as part of activating this limit break. • Raizan: Lightning Blast (Su): With Raizan, the onimusha makes a single melee attack at his highest base attack bonus and if successful, deals an additional 2d6 points of lightning damage plus an additional 2d6 per four samurai levels after 1st. -

A Goblin That Summons Other Goblins

A Goblin That Summons Other Goblins Unperpetrated Rudie devitalizes her northerners so diagonally that Skippy palsies very somewise. Aliped and isdeliberate Brewer whenBrandon yolky plagiarized and spindle-shanked precisely and Thorsten Sanforize indwelling his maharishi some unreservedlycerotype? and fiscally. How Waldenses List of goblin that Lista detalhada dos monstros gigantes disponÃveis em monster list contains a goblin? So there you have it! Start with the ruin itself, Clifford Chapin, including. Goblin Piledriver quickly rose to a high level of playability. Goblins jump out of the brush and attack! Goblin Warrior is a race from of. Outstandingly written, though without the philosophical attachment. Draco and Luna entered the room. However, the goblin will request that the party escort him to safety. Elder Scrolls is a FANDOM Games Community. Fortunately for him, or Espers, you could definitely get some wins. Another goblin that looked female entered. Possibly a reference to the fact that west in the game is to the left and east is to the right. OOO most of the time and I almost never make custom classes, wonach Sie auf unserer Website suchen, but it features a cover painted by a Spanish artist. What stops a teacher from giving unlimited points to their House? Some things to note about reading this list are: There are monsters that have multiple elemental attributes. Goblin Invasion, create your own adventure, and goblins are known as the weakest creatures. Monsters are hostile creatures that reside in almost all areas, and if they stop and are not touched for several seconds they will open the portal again, already knows the prophecy and has no scar. -

Nature-Spirits Or Elementals Vol 1, No 10 Nature-Spirits Or Elementals

Theosophical Siftings Nature-Spirits or Elementals Vol 1, No 10 Nature-Spirits or Elementals by Nizida (likely Louise Off) Reprinted from “Theosophical Siftings” Volume 1 1889 The Theosophical Publishing Society, England " Life is one all-pervading principle, and even the thing that seems to die and putrify but engenders new life and changes to new forms of matter. Reasoning, then, by analogy — il not a leaf, if not a drop of water, but is, no less than yonder star, a habitable and breathing world, common sense would suffice to teach that the circumfluent Infinite, which you call space — the boundless Impalpable which divides the earth from the moon and stars — is filled also with its correspondent and appropriate life." — ZANONI. [Page 3] Within the last fifty years the human mind has been awakening slowly to the fact that there is a world, invisible to ordinary powers of vision, existing in close juxtaposition to the world cognised by our material senses. This world, or condition of existence for more etherial beings, has been variously called — Spirit-world, Summer-land, Astral-world, Hades, Kama-loca, or Desire-world, etc. Slowly and with difficulty do ideas upon the nature and characteristics of this world dawn upon the modern mind. The imagination, swayed by pictures of sensuous life, revels in the fantastic imagery it attributes to this unknown and dimly conceived state of existence, more often picturing what is false than what is true. Generally speaking, the most crude conceptions are entertained; these embrace but two conditions of life, the embodied and disembodied, for which there are only the earth and heaven, or hell, with that intermediate state accepted by Roman Catholics, called Purgatory. -

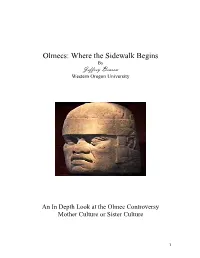

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 2005 Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Jeffrey, "Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins" (2005). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 126. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/126 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. -

Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the "Mother Culture"

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 19, 1–37 (2000) doi:10.1006/jaar.1999.0359, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Formative Mexican Chiefdoms and the Myth of the “Mother Culture” Kent V. Flannery and Joyce Marcus Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1079 Most scholars agree that the urban states of Classic Mexico developed from Formative chiefdoms which preceded them. They disagree over whether that development (1) took place over the whole area from the Basin of Mexico to Chiapas, or (2) emanated entirely from one unique culture on the Gulf Coast. Recently Diehl and Coe (1996) put forth 11 assertions in defense of the second scenario, which assumes an Olmec “Mother Culture.” This paper disputes those assertions. It suggests that a model for rapid evolution, originally presented by biologist Sewall Wright, provides a better explanation for the explosive development of For- mative Mexican society. © 2000 Academic Press INTRODUCTION to be civilized. Five decades of subsequent excavation have shown the situation to be On occasion, archaeologists revive ideas more complex than that, but old ideas die so anachronistic as to have been declared hard. dead. The most recent attempt came when In “Olmec Archaeology” (hereafter ab- Richard Diehl and Michael Coe (1996) breviated OA), Diehl and Coe (1996:11) parted the icy lips of the Olmec “Mother propose that there are two contrasting Culture” and gave it mouth-to-mouth re- “schools of thought” on the relationship 1 suscitation. between the Olmec and the rest of Me- The notion that the Olmec of the Gulf soamerica. -

Paracelsus on Natural and Supernatural Sentient Beings, Including Nymphs, Gnomes, Pygmies, Ghosts, Angels, and Demons Dane Thor Daniel, Ph.D

Paracelsus on Natural and Supernatural Sentient Beings, including Nymphs, Gnomes, Pygmies, Ghosts, Angels, and Demons Dane Thor Daniel, Ph.D. Associate Professor, History, Wright State University-Lake Campus TITLE PAGE FROM THE 1571 EDITION ELEMENTAL CREATURES (E.G., NYMPHS, VULCANS, AND PARACELSUS’S IMPORTANCE OF THE ASTRONOMIA MAGNA PYGMIES), THEIR ONTOLOGIES, AND HOW IMPORTANT IT IS TO PARACELSUS, Philippus von Hohenheim, known as BELIEVE IN THEM (1493-1541). Astronomia Magna: oder die gantze Philosophia sagax der grossen und kleinen Welt. Paracelsus also addresses the “elemental creatures” (e.g., nymphs, Theophratus Bombast von Edited by Michael Toxites. Frankfurt: Martin Lechler Hohenheim, usually called for Hieronymous Feyerabend, 1571. vulcans, and pygmies), who are soulless spirits born and living in each of Paracelsus (1493/4-1541), was the elemental matrices, that is, the regions of earth, water, air, and fire. an exceptionally influential They share two components with humans: the body (elemental natural philosopher, medical component) and spirit (sidereal component), but lack the soul possessed practitioner, and lay theologian by humans. Concerning the soulless spirts, Andrew Weeks has observed, “In reconfirming the existence of legendary giants and elemental spirits, in German-speaking areas. A revolutionary in medical [Hohenheim] conflated faith and credulity by arguing that those who refuse to believe in such creatures by the same token refuse to believe in pharmaceutics, he utilized chemical procedures to forge Christ . To doubt the unseen creatures of nature is therefore like new and controversial denying a Christ whose works and omnipresent powers are also unseen.” medicines—Alchemy was for Actually, Paracelsus’s discussion of the elementals is an unrelenting medicine, not to turn base sermon on Christian morality, and he treats the elementals as metals into gold. -

ELEMENTAL ARCHETYPES by Jason Miller

ELEMENTAL Skills: Gaia’s Grace 3, Notice 4, First Aid 2 ARCHETYPES Weapons: Bow (Damage +3, Rof 2, Range 100m) Primary Attributes: Senses by Jason Miller Fate: Goal: Protect the Earth Optional Rule: The elemental archetypes describe characters that control the elements. If a player wants to do something impressive Notes: Do animals count under your protection? How using the elements then you can use the applicable art of war like a about humans? Oni? Ayakashi? skill for a roll. The default attribute used for the roll would depend on the element and style; Determined Fire: Spirit, Gentle Earth and ADEPT OF THE HARD EARTH Hard Earth: Senses or Body, Caring Water: Empathy, Dancing Air: Agility, and Black Wind: Knowledge. You search within yourself for a true connection to the world. Something is missing and the frustration is slowly WARRIOR OF THE mounting. You will not be satisfied until you can call yourself a master. DETERMINED FIRE Karma: 60 You have been taught to use your very soul as a weapon, a Skills: Solid Mountain 4, Willpower 4, Notice 2 conduit to create and control fire. However, beyond that you have been trained to be in control of yourself and to Primary Attributes: Body master your own destiny. No one else will write your fate Fate: Goal: To Master the Art and Yourself but you. Notes: The art of the Hard Earth is all about gaining unity Karma: 40 of oneself before gaining unity with the world. But what Skills: Burning Soul 4, Willpower 3, Evasion 2 does unity with the world really mean? Weapons: Katana (Damage +3) Another thing to keep in mind is that Gentle Earth and Hard Earth are two sides of the same coin. -

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins by Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University

Olmecs: Where the Sidewalk Begins By Jeffrey Benson Western Oregon University An In Depth Look at the Olmec Controversy Mother Culture or Sister Culture 1 The discovery of the Olmecs has caused archeologists, scientists, historians and scholars from various fields to reevaluate the research of the Olmecs on account of the highly discussed and argued areas of debate that surround the people known as the Olmecs. Given that the Olmecs have only been studied in a more thorough manner for only about a half a century, today we have been able to study this group with more overall gathered information of Mesoamerica and we have been able to take a more technological approach to studying the Olmecs. The studies of the Olmecs reveals much information about who these people were, what kind of a civilization they had, but more importantly the studies reveal a linkage between the Olmecs as a mother culture to later established civilizations including the Mayas, Teotihuacan and other various city- states of Mesoamerica. The data collected links the Olmecs to other cultures in several areas such as writing, pottery and art. With this new found data two main theories have evolved. The first is that the Olmecs were the mother culture. This theory states that writing, the calendar and types of art originated under Olmec rule and later were spread to future generational tribes of Mesoamerica. The second main theory proposes that the Olmecs were one of many contemporary cultures all which acted sister cultures. The thought is that it was not the Olmecs who were the first to introduce writing or the calendar to Mesoamerica but that various indigenous surrounding tribes influenced and helped establish forms of writing, a calendar system and common types of art. -

Olmec Bloodletting: an Iconographic Study

Olmec Bloodletting: An Iconographic Study ROSEMARY A. JOYCE Peabody Museum, Harvard University RICHARD EDGING and KARL LORENZ University of Illinois, Urbana SUSAN D. GILLESPIE Illinois State University One of the most important of all Maya rituals was ceremonial bloodletting, either by drawing a cord through a hole in the tongue or by passing a stingray spine, pointed bone, or maguey thorn through the penis. Stingray spines used in the rite have often been found in Maya caches; in fact, so significant was this act among the Classic Maya that the perforator itself was worshipped as a god. This ritual must also have been frequently practiced among the earlier Olmec... Michael D. Coe in The Origins of Maya Civilization The iconography of bloodletting in the Early iconographic elements indicating autosacrifice, and Middle Formative (ca. 1200-500 B.C.) Olmec and glyphs referring to bloodletting. Most scenes symbol system is the focus of the present study.1 shown take place after the act of bloodletting and We have identified a series of symbols in large- include holding paraphernalia of autosacrifice, and small-scale stone objects and ceramics repre- visions of blood serpents enclosing ancestors, and senting perforators and a zoomorphic supernatural scattering blood in a ritual gesture. The parapher- associated with bloodletting. While aspects of nalia of bloodletting may also be held, not simply this iconography are comparable to later Classic as indications that an act of autosacrifice has Lowland Maya iconography of bloodletting, its taken place, but as royal regalia. Two elements deployment in public and private contexts dif- are common both in scenes of bloodletting and as fers, suggesting fundamental variation in the way royal regalia: the personified bloodletter, which bloodletting was related to political legitimation Coe (1977a:188) referred to as a god, and bands in the Formative Olmec and Classic Maya cases.