Using Hip-Hop As an Empowerment Tool for Young Adults : an Exploratory Study : a Project Based Upon Independent Investigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

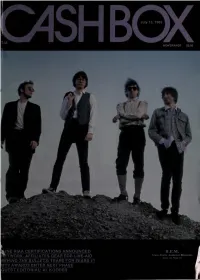

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

Mayan Language Revitalization, Hip Hop, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Linguistics Faculty Publications Linguistics 3-2016 Mayan Language Revitalization, Hip Hop, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala Rusty Barrett University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub Part of the Communication Commons, Language Interpretation and Translation Commons, and the Linguistics Commons Repository Citation Barrett, Rusty, "Mayan Language Revitalization, Hip Hop, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala" (2016). Linguistics Faculty Publications. 72. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub/72 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Linguistics at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mayan Language Revitalization, Hip Hop, and Ethnic Identity in Guatemala Notes/Citation Information Published in Language & Communication, v. 47, p. 144-153. Copyright © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The document available for download is the authors' post-peer-review final draft of the ra ticle. Digital Object Identifier (DOI) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2015.08.005 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/lin_facpub/72 Mayan language revitalization, hip hop, and ethnic identity in Guatemala Rusty Barrett, University of Kentucky to appear, Language & Communiction (46) Abstract: This paper analyzes the language ideologies and linguistic practices of Mayan-language hip hop in Guatemala, focusing on the work of the group B’alam Ajpu. -

Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age.” I Am Grateful This Is the First 2020 Issue JHHS Is Publishing

Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Travis Harris Managing Editor Shanté Paradigm Smalls, St. John’s University Associate Editors: Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, Georgia State University Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Willie "Pops" Hudson, Azusa Pacific University Javon Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Elliot Powell, University of Minnesota Books and Media Editor Marcus J. Smalls, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Conference and Academic Hip Hop Editor Ashley N. Payne, Missouri State University Poetry Editor Jeffrey Coleman, St. Mary's College of Maryland Global Editor Sameena Eidoo, Independent Scholar Copy Editor: Sabine Kim, The University of Mainz Reviewer Board: Edmund Adjapong, Seton Hall University Janee Burkhalter, Saint Joseph's University Rosalyn Davis, Indiana University Kokomo Piper Carter, Arts and Culture Organizer and Hip Hop Activist Todd Craig, Medgar Evers College Aisha Durham, University of South Florida Regina Duthely, University of Puget Sound Leah Gaines, San Jose State University Journal of Hip Hop Studies 2 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/1 2 Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Elizabeth Gillman, Florida State University Kyra Guant, University at Albany Tasha Iglesias, University of California, Riverside Andre Johnson, University of Memphis David J. Leonard, Washington State University Heidi R. Lewis, Colorado College Kyle Mays, University of California, Los Angeles Anthony Nocella II, Salt Lake Community College Mich Nyawalo, Shawnee State University RaShelle R. -

WINNERS Begins Page 28 SPOTLIGHT: Z -100 See Page 26 DALLAS RADIO MARKET ® See Page 24

ICD 08120 YYY Y YYJ. .M1AAJ..4YM 3-D I GI I 9 .b ÿ ii 1466 í'4ELk49B Chr_E vLti 9 l 374, tLM VCti z"' w LGhv bLACH CA 91äv7 ammo z WINNERS Begins page 28 SPOTLIGHT: Z -100 See page 26 DALLAS RADIO MARKET ® See page 24 VOLUME 97 NO. 37 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT SEPTEMBER 14, 1985/$3.50 (U.S.) Metal Mining Mounts LYRIC ROW: NEW DEVELOPMENTS August Yields Bumper Crop PMRC Says Beach Boys' Mike Love Gave Seed Money Of Gold, Platinum Albums problem [of lyrics], and he was very recording artists." BY BILL HOLLAND sympathetic." The purpose of the hearing, ac- The two other albums to go plati- WASHINGTON Part of the seed In a concurrent development, an cording to the staff source, is to "air BY PAUL GREIN num in August were both by repeat- money for the Parents Music Re- announcement came from Capitol the issue, educate the Senate and But LOS ANGELES The Recording In- ing acts. Motley Crue's "Shout At source Center (PMRC), the poliuical- Hill that the witness list for the bring things out in the open." dustry Assn. of America (RIAA) The Devil" is the group's second ly well -connected group of Wash- Sept. 19 Senate Commerce Commit- the source admits that the hearing awarded an unseasonally high total straight platinum album; Dire ington mothers that has been wag- tee hearing on rock lyrics will in- could "bring some slight pressure PMRC and the of 16 gold albums in August, com- S xaits' "Brothers In Arms" is also ing a fight against so-called ' porn clude recording artis-s Frank Zappa on the groups [the to come to a pared to 11 in the same month last their second platinum album, but rock," was a gift from Mike Love of and Dee Snyder. -

Cash Box Introduced the Unique Weekly Feature

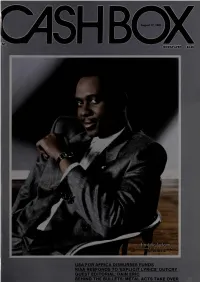

MB USA FOR AFRICA DISBURSES FUNDS RIAA RESPONDS TO EXPLICIT LYRICS’ OUTCRY GUEST EDITORIAL: PAIN ERIC BEHIND THE BULLETS: METAL ACTS TAKE OVER new laces to n September 10, 1977, Cash Box introduced the unique weekly feature. New Faces To Watch. Debuting acts are universally considered the life blood of the recording industry, and over the last seven years Cash Box has been first to spotlight new and developing artists, many of whom have gone on to chart topping successes. Having chronicled the development of new talent these seven years, it gives us great pleasure to celebrate their success with our seventh annual New Faces To Watch Supplement. We will again honor those artists who have rewarded the faith, energy, committment and vision of their labels this past year. The supplemenfs layout will be in easy reference pull-out form, making it a year-round historical gudie for the industry. It will contain select, original profiles as well as an updated summary including chart histories, gold and platinum achievements, grammy awards, and revised up-to-date biographies. We know you will want to participate in this tribute, showing both where we have been and where we are going as an industry. The New Faces To Watch Supplement will be included in the August 31st issue of Cash Box, on sale August The advertising deadline is August 22nd. Reserve Advertising Space Now! NEW YORK LOS ANGELES NASHVILLE J.B. CARMICLE SPENCE BERLAND JOHN LENTZ 212-586-2640 213-464-8241 615-244-2898 9 C4SH r BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT -

![1 Title Page Needs Pasted, Roman Numeral I [Not Shown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4431/1-title-page-needs-pasted-roman-numeral-i-not-shown-1504431.webp)

1 Title Page Needs Pasted, Roman Numeral I [Not Shown]

“IT’S BIGGER THAN HIP HOP”: POPULAR RAP MUSIC AND THE POLITICS OF THE HIP HOP GENERATION A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by DEREK EVANS Dr. Tola Pearce, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled “IT’S BIGGER THAN HIP HOP”: POPULAR RAP MUSIC AND THE POLITICS OF THE HIP HOP GENERATION Presented by Derek J. Evans A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. ________________________________________ Professor Ibitola O. Pearce ________________________________________ Professor David L. Brunsma ________________________________________ Professor Cynthia Frisby …to Madilyn. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my unending gratitude to Dr. Tola Pearce for her support, guidance and, most of all, her patience. Many thanks to Dr. David Brunsma for providing me with fresh perspectives and for showing great enthusiasm about my project. I would like to thank Dr. Cynthia Frisby for helping me recognize gaps in my research and for being there during crunch-time. I would also like to thank my fellow sociology graduate students and colleagues for letting me bounce ideas off of them, for giving me new ideas and insights, and for pushing me to finish. Lastly, I would like to thank my wife Samantha for sticking by my side through it all. You are my rock. Shouts to Ice -

The Future Is History: Hip-Hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity

The Future is History: Hip-hop in the Aftermath of (Post)Modernity Russell A. Potter Rhode Island College From The Resisting Muse: Popular Music and Social Protest, edited by Ian Peddie (Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2006). When hip-hop first broke in on the (academic) scene, it was widely hailed as a boldly irreverent embodiment of the postmodern aesthetics of pastiche, a cut-up method which would slice and dice all those old humanistic truisms which, for some reason, seemed to be gathering strength again as the end of the millennium approached. Today, over a decade after the first academic treatments of hip-hop, both the intellectual sheen of postmodernism and the counter-cultural patina of hip-hip seem a bit tarnished, their glimmerings of resistance swallowed whole by the same ubiquitous culture industry which took the rebellion out of rock 'n' roll and locked it away in an I.M. Pei pyramid. There are hazards in being a young art form, always striving for recognition even while rejecting it Ice Cube's famous phrase ‘Fuck the Grammys’ comes to mind but there are still deeper perils in becoming the single most popular form of music in the world, with a media profile that would make even Rupert Murdoch jealous. In an era when pioneers such as KRS-One, Ice-T, and Chuck D are well over forty and hip-hop ditties about thongs and bling bling dominate the malls and airwaves, it's noticeably harder to locate any points of friction between the microphone commandos and the bourgeois masses they once seemed to terrorize with sonic booms pumping out of speaker-loaded jeeps. -

Fat Boys the Fat Boys Are Back Mp3, Flac, Wma

Fat Boys The Fat Boys Are Back mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: The Fat Boys Are Back Country: Canada Released: 1985 MP3 version RAR size: 1261 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1807 mb WMA version RAR size: 1520 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 799 Other Formats: ASF MP2 MIDI MOD APE AC3 ADX Tracklist Hide Credits The Fat Boys Are Back A1 6:10 Backing Vocals – Alyson Williams, Fonda Rae, Michelle Cobbs A2 Don't Be Stupid 5:40 A3 Human Beat Box 3:16 A4 Yes, Yes, Y'All 5:16 B1 Hard Core Reggae 5:58 Pump It Up B2 6:25 Backing Vocals – Danny Harris, David Reeves , Kurtis Blow, Larry Green Jr. B3 Fat Boys Scratch 5:02 B4 Rock 'N' Roll 6:00 Companies, etc. Distributed By – Sutra Records, Inc. Marketed By – Sutra Records, Inc. Credits Design – Lynda West Executive-Producer – Art Kass, Charles Settler Mixed By – Dave Ogrin, Kurtis Blow Other [Musicians] – Danny Harris, Dave Ogrin, David Reeves, Kurtis Blow, Steve Beck Photography – Raeanne Rubenstein Producer – Kurtis Blow Written-By – D. Wimbley* (tracks: A1, A3 to B4), D. Harris* (tracks: B4), D. Robinson* (tracks: A1, A3, to B2, B4), D. Reeves* (tracks: B1, B2), K. Blow* (tracks: A1, A2, A4 to B2, B4), M. Morales* (tracks: A1, A3 to B2, B4) Notes (P)&(C) 1984 Sutra Records, Inc. Marketed and distributed by Sutra Records, Inc. Mastered at Frankford/Wayne Mastering Labs Produced for Kuwa Music, Inc. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 85931-1016-1 3 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Fat Boys Are Back (LP, SUS 1016 Fat Boys Sutra Records -

From Slavery to Hip-Hop: Punishing Black Speech and What's

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 52 Justice Reform 2016 From Slavery to Hip-Hop: Punishing Black Speech and What’s “Unconstitutional” About Prosecuting Young Black Men Through Art Donald F. Tibbs Drexel University, Thomas R. Kline School of Law Shelly Chauncey Drexel University, Thomas R. Kline School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Donald F. Tibbs and Shelly Chauncey, From Slavery to Hip-Hop: Punishing Black Speech and What’s “Unconstitutional” About Prosecuting Young Black Men Through Art, 52 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 033 (2016), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol52/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Slavery to Hip-Hop: Punishing Black Speech and What’s “Unconstitutional” About Prosecuting Young Black Men Through Art Donald F. Tibbs* Shelly Chauncey Writing rap lyrics—even disturbingly graphic lyrics, like defendant’s—is not a crime.1 Our criminal justice system is in an existential and constitutional crisis. We no longer know who we are or who we want to be. Over the past two decades, America has waged an increasingly punitive war on crime, and the casualties of that war have disproportionately been people of color; most specifically the young Black2 men and * Associate Professor of Law, Thomas R. -

Who's Who in Pop Record Production

WHO'S WHO IN POP RECORD PRODUCTION The following is a list of producers who had at least one single and/or album in the Top Pop 100 charts last year (1986). The producer's name is followed by the (S) song title(s) and/or (LP) album title(s) in quotes, with the artist's name in all capitol letters, followed by a slash and the name(s) of any co- producer(s). Colonel Abrams (S)-(LP)-"Colonel Abrams"-COLONEL ABRAMS-/ /Richard The Bunnymen (S)-(LP)-"Songs To Learn And Sing"-ECHO & THE James Burgess/Rick Dees BUNNYMEN-/Ian Broudie/Bill Drummond/Hugh Jones William Ackerman (S)-(LP)-"Winter's Solstice"-VARIOUS-/Dawn Atkinson Richard James (S)-"Can't Wait Another Minute"-FIVE Alabama (S)-(LP)-"Christmas"-ALABAMA-/Harold Shedd Burgess STAR-/(LP)-"Colonel Abrams"-COLONEL ABRAMS-/Colonel "Alabama Greatest Hits"-ALABAMA-/Harold Shedd Abrams/ /Rick Dees "The Touch"-ALABAMA-/Harold Shedd T-Bone Burnett (S)-(LP)-"King Of America"-ELVIS COSTELLO & THE Teneen Ali (S)-"For Tonight"-NANCY MARTINEZ-/Sergio Munzibal(LP)- ATTRACTIONS-/Declan Patrick A. MacManus Dave Allen (S)-"In Between Days"-THE CURE-/Robert Smith(LP)- Joe Busby (S)-(LP)-"Al I In Love"-NEW EDITION-/Bill Dern Tom Allom (S)-"This Could Be The Night"-LOVERBOY-/Paul Dean Jonathan Cain (S)-"Working Class Man"-JIMMY BARNES-/UP)- "Lead A Double Life"-LOVERBOY-/Paul Richard Calandra (S)-(LP)-"Breakout"-SPYRO GYRA-/Jay Becknestein Dean(LP)-"Turbo"-JUDAS PRIEST-/ The Call (S)-(LP)-"Reconciled"-THE CALL-/Michael Been Pete Anderson (S)-(LP)-"Guitars, Cadillacs, Etc., Etc."-DWIGHT Reggie Calloway (S)-"Headlines"-MIDNIGHT -

Punk Section

A “nihilistic dreamboat to negation”? The cultural study of death metal and the limits of political criticism Michelle Phillipov Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of English University of Adelaide October 2008 CONTENTS Contents ................................................................................................................... II Abstract.................................................................................................................... IV Declaration ........................................................................................................ VI Acknowledgements ............................................................................. VII Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 From heavy to extreme metal ............................................................................................. 9 The politics of cultural studies .......................................................................................... 20 Towards an understanding of musical pleasure ............................................................. 34 Chapter 1 Popular music studies and the search for the “new punk”: punk, hip hop and dance music ........................................................................ 38 Punk studies and the persistence of politics ................................................................... 39 The “new punk”: rap and hip hop .................................................................................. -

Fat Boys the Best Part of the Fat Boys Mp3, Flac, Wma

Fat Boys The Best Part Of The Fat Boys mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: The Best Part Of The Fat Boys Country: US Released: 1987 MP3 version RAR size: 1718 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1671 mb WMA version RAR size: 1487 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 848 Other Formats: AUD VQF AC3 DXD WMA MP3 APE Tracklist Hide Credits The Fat Boys Are Back 1 4:18 Written-By – D. Wimbley*, D. Robinson*, K. Blow*, M. Morales* Jail House Rap 2 Written-By – D. Wimbley*, D. Robinson*, D. Reeves*, K. Blow*, L. Smith*, M. Morales*, S. 4:49 Abbatiello* Human Beat Box 3 2:16 Written-By – D. Wimbley*, M. Morales* In The House 4 3:39 Producer – Dave Ogrin, Gordon Pickett, Mark MoralesWritten-By – G. Pickett*, M. Morales* All You Can Eat 5 5:21 Written-By – D. Wimbley*, D. Robinson*, K. Blow*, M. Morales* Fat Boys 6 4:22 Written-By – D. Wimbley*, K. Blow*, M. Morales*, R. Miller*, W. Waring* Sex Machine 7 4:01 Producer – Dave OgrinWritten-By – B. Byrd*, J. Brown*, R. Lenkoff* Stick 'Em 8 4:26 Written-By – D. Wimbley*, D. Robinson*, M. Morales* Hard Core Reggae 9 4:05 Written-By – D. Wimbley*, D. Robinson*, D. Reeves*, K. Blow*, M. Morales* Rock 'N' Roll 10 3:58 Written-By – D. Wimbley*, D. Harris*, D. Robinson*, K. Blow*, M. Morales* Credits Producer – Kurtis Blow (tracks: 1 to 3, 5, 6, 8 to 10) Notes (c)(p) 1987 Sutra Records Manufactured by Améric Disc Inc. Made in Canada.