A Qualitative Case Study of Three Elementary Teachers' Experiences Integrating Literacy and Social Studies Rebecca L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Melvette Melvin Davis

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts DAUGHTERS READING AND RESPONDING TO AFRICAN AMERICAN YOUNG ADULT LITERATURE: THE UMOJA BOOK CLUB A Dissertation in English by Melvette Melvin Davis © 2009 Melvette Melvin Davis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 The dissertation of Melvette Melvin Davis was reviewed and approved* by the following: Keith Gilyard Distinguished Professor of English Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Linda Selzer Assistant Professor of English Julia Kasdorf Associate Professor of English and Women’s Studies Jeanine Staples Assistant Professor of Education Robert Edwards Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature Director of Graduate Studies, Department of English *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation details efforts undertaken by the researcher to address a group of African American adolescent girls’ need for positive role models and Black female-centered spaces where discussions of issues such as Black female identity, voice, and relationships could take place. During the 2005-2006 school year, I facilitated a book club with ninth and tenth grade girls participating in the Umoja Youth Empowerment Program. This book club provided an opportunity for teen girls to read and discuss with peers and adult mentors issues in young adult texts written by African American female authors. This book club aimed to examine how African American female readers discussed African American young adult literature (AAYAL) in an out-of-school context. In Chapter One, I outline the theoretical framework that undergirds this study. It is largely informed by feminist and Black feminist/womanist theories that offer a way to discuss social, personal, cultural, and literacy issues concerning African American adolescent girls and women. -

4Th Grade - DRA 40-50 First Title Last Name Name Sounder William Armstrong All About Owls Jim Arnosky Mr

4th Grade - DRA 40-50 First Title Last Name Name Sounder William Armstrong All About Owls Jim Arnosky Mr. Popper's Penguins Richard Atwater American Girl (series of books) various authors 39 Clues various authors Poppy (series) Avi Lynne The Indian in the Cupboard Banks Reid Lynne Mystery of the Cupboard Banks Reid The House With a Clock in Its Walls John Bellairs A Gathering of Days Joan Blos Fudge-a-Mania Judy Blume Superfudge Judy Blume Iggie's House Judy Blume Toliver's Secret Esther Brady Caddie Woodlawn Carol Ryrie Brink Nasty Stinky Sneakers Eve Bunting After the Goat Man Betsy Byars The Computer Nut Betsy Byars Dear Mr. Henshaw Beverly Cleary Henry and the Paper Route Beverly Cleary Strider Beverly Cleary Frindle Andrew Clements The Landry News Andrew Clements Jake Drake: Teacher's Pet Andrew Clements Aliens Ate My Homework Bruce Coville The Monster's Ring Bruce Coville My Teacher is an Alien (series) Bruce Coville Fantastic Mr. Fox Roald Dahl James and the Giant Peach Roald Dahl Twits Roald Dahl Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Roald Dahl Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator Roald Dahl Matilda Roald Dahl Danny, the Champion of the World Roald Dahl Nothing's Fair in Fifth Grade Barthe DeClements Morning Girl Michael Dorros Barefoot: Escape on the Pamela Edwards Underground… Zinnia and Dot Lisa Ernst The Great Brain (series) John Fitzgerald Harriet the Spy Louise Fitzhugh Jim Ugly Sid Fleischman The Ghost on Saturday Night Sid Fleischman Whipping Boy Sid Fleischman Seedfolks Paul Fleischman Flying Solo Ralph Fletcher And Then What -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

All-Bright Court, Imani All Mine by Connie Rose Porter

A Reader's Guide All-Bright Imani All Mine by Court Connie Rose Porter by Connie Rose Porter • All-Bright Court • Imani All Mine • Both Books • About the Author • A Conversation with Connie Rose Porter www.houghtonmifflinbooks.com 1 of 7 Copyright (c) 2003 Houghton Mifflin Company, All Rights Reserved All-Bright Court In the upstate New York mill town of Lackawanna, the company-built housing project known as All-Bright Court represents everything its residents have dreamed of — jobs, freedom, and a future. The outcome of those dreams is the stuff of Connie Porter's acclaimed debut novel. Through twenty years, as the promises of the 1960s give way to hardship and upheaval, Porter chronicles the loves, hopes, troubles, triumphs, and ambitions of Mississippi-born Sam and Mary Kate Taylor and their neighbors. As the late 1970s fade the Court's bright colors and a people’s optimism, young Mikey Taylor — gifted, ambitious, and proud — comes to embody an entire community's dreams and disappointments. For Discussion 1. Porter has said that in this novel, "The reader can see the impact of the political life of this country on a group of people." What impact do the major events and issues in American "political life" have on the people of All-Bright Court? How are some of these political and social issues still important? 2. What arguments do the characters present for and against playing by the white man’s rules — for example: getting an education, paying taxes, working hard? In what circumstances are those arguments voiced? What are the desired and actual results of each way of acting? In what ways do the same arguments apply today for black Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Asian- Americans? 3. -

Pleasant Company's American Girls Collection

PLEASANT COMPANY’S AMERICAN GIRLS COLLECTION: THE CORPORATE CONSTRUCTION OF GIRLHOOD by NANCY DUFFEY STORY (Under the direction of JOEL TAXEL) ABSTRACT This study examines the modes of femininity constructed by the texts of Pleasant Company’s The American Girls Collection in an effort to disclose their discursive power to perpetuate ideological messages about what it means to be a girl in America. A feminist, post structual approach, informed by neo-Marxist insights, is employed to analyze the interplay of gender, class, and race, as well as the complex dynamics of the creation, marketing, publication and distribution of the multiple texts of Pleasant Company, with particular emphasis given to the historical fiction books that accompany the doll-characters. The study finds that the selected texts of the The American Girls Collection position subjects in ways that may serve to reinforce rather than challenge traditional gender behaviors and privilege certain social values and social groups. The complex network of texts positions girls as consumers whose consumption practices may shape identity. The dangerous implications of educational books, written, at least in part, as advertisements for products, is noted along with recommendations that parents and teachers assist girl-readers in engaging in critical inquiry with regard to popular culture texts. INDEX WORDS: Pleasant Company, American Girls Collection, feminism, post- structuralism, gender, consumption, popular culture PLEASANT COMPANY’S AMERICAN GIRLS COLLECTION: THE CORPORATE CONSTRUCTION OF GIRLHOOD by NANCY DUFFEY STORY B.A., LaGrange College, 1975 M.S.W., University of Georgia, 1977 M.A., University of Georgia, 1983 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2002 © 2002 Nancy Duffey Story All Rights Reserved PLEASANT COMPANY’S AMERICAN GIRLS COLLECTION: THE CORPORATE CONSTRUCTION OF GIRLHOOD by NANCY DUFFEY STORY Major Professor: Joel Taxel Committee: Elizabeth St. -

Level Q (31/32) Title Author 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins Dr

Level Q (31/32) Title Author 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins Dr. Seuss Addy Learns a Lesson Connie Porter Addy Saves the Day Connie Porter Aliens Ate My Homework Bruce Coville All-of-a-Kind Family Sydney Taylor Anastasia Again! Lois Lowry Anastasia at this Address Lois Lowry Anastasia at Your Service Lois Lowry Anastasia Has the Answers Lois Lowry Anastasia Krupnik Lois Lowry Anastasia On Her Own Lois Lowry Anastasia’s Chosen Career Lois Lowry And Still the Turtle Watched Sheila Callahan Animal Ark Series Ben Baglio Black-Eyed Susan: a novel Jennifer Armstrong Bunnicula James Howe Bunnicula Strikes Again! James Howe By the Shores of Silver Lake Laura Ingalls Wilder Centerburg Tales Robert McCloskey Changes for Addy Connie Porter Changes for Felicity Valerie Tripp Changes for Josefina Valerie Tripp Changes for Kirsten Connie Porter Changes for Molly Valerie Tripp Changes for Samantha Valerie Tripp Class Trip to the Cave of Doom Kate McMullan Dear Mr. Henshaw Beverley Cleary Do You Know Me Nancy Farmer Fantastic Mr. Fox Roald Dahl Farmer Boy Laura Ingalls Wilder Felicity Learns a Lesson Valerie Tripp Felicity Saves the Day Valerie Tripp Felicity’s Surprise Valerie Tripp Fourth Grade Celebrity Patricia Giff Fudge-a-Mania Judy Blume Galimoto Karen Williams Ghost on Saturday Night Sid Fleischman Go Fish Mary Stolz Hannah and the Angels Series Jean Van Leeuwen Happy Birthday, Addy! Connie Porter Happy Birthday, Felicity Valerie Tripp Happy Birthday, Josefina Valerie Tripp Happy Birthday, Kirsten! Connie Porter Happy Birthday, Molly Valerie Tripp Happy Birthday, Samantha! Valerie Tripp Help! I’m a Prisoner in the Library Eth Clifford Henry and the Paper Route Beverley Cleary Hide and Seek Fog Alvin Tresselt Homer Price Robert McCloskey Horrors of the Haunted Museum R. -

Young Adult Literature and Multimedia a Quick Guide

Young Adult Literature and Multimedia A Quick Guide Mary Ann Harlan David V. Loertscher Sharron L. McElmeel 4th Edition Hi Willow Research & Publishing 2008 Copyright ! 2008 Hi Willow Research & Publishing ii All Rights Reserved. ISBN-10: 1-933170-39-5 ISBN-13: 978-1-933170-39-8 Content current as of August 11, 2008. Hi Willow Research & Publishing 312 South 1000 East Salt Lake City, UT 84102 Distributed by LMC Source at www.lmcsource.com Mail orders to: LMC Source P.O. Box 131266 Spring, TX 77393 Email orders to [email protected] Order by phone at 800-873-3043 Copies of up to 3 pages may be made for school or district in-service workshops as long as the source with ordering information is included in the reprints. All other copying is prohibited without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permission can be sought by email at [email protected] This book is supplemented by a website, two wikis and a supplementary work. These are described in the introduction. Acknowledgements Appreciation is extended to graduate students in Young Adult Materials at San Jose State University who wrote and contributed to some of the pages in this volume. Their names are included on the specific pages they helped to construct both within this book and in online contributions on the web. And thank you to Rebecca Brodegard who wrote a number of the pages and served as general editor for the entire project. Thanks also to Richie Partington, graduate assistant in the School of Library and Information Science, for revising and adding to a number of pages. -

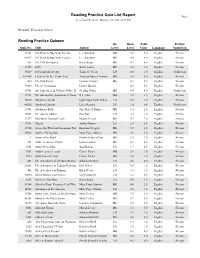

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Monday, 10/13/08, 12:49 PM

Reading Practice Quiz List Report Page 1 Accelerated Reader®: Monday, 10/13/08, 12:49 PM McAuliffe Elementary School Reading Practice Quizzes Int. Book Point Fiction/ Quiz No. Title Author Level Level Value Language Nonfiction 18751 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw MG 3.9 5.0 English Fiction 80179 101 Ways to Bug Your Teacher Lee Wardlaw MG 4.4 8.0 English Fiction 661 The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars MG 4.7 4.0 English Fiction 11592 2095 Jon Scieszka MG 3.8 1.0 English Fiction 30629 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola LG 4.4 1.0 English Nonfiction 109460 4 Kids in 5E & 1 Crazy Year Virginia Frances Schwar MG 3.8 6.0 English Fiction 413 The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson MG 4.7 2.0 English Fiction 79509 The A+ Custodian Louise Borden 4.5 0.5 English Fiction 17601 Abe Lincoln: Log Cabin to White Ho Sterling North MG 8.4 4.0 English Nonfiction 14931 The Abominable Snowman of Pasad R.L. Stine MG 3.0 3.0 English Fiction 18652 Abraham Lincoln Ingri/Edgar Parin D'Aula LG 5.2 1.0 English Fiction 40525 Abraham Lincoln Lucia Raatma LG 3.6 0.5 English Nonfiction 29341 Abraham's Battle Sara Harrell Banks MG 5.3 2.0 English Fiction 17651 The Absent Author Ron Roy LG 3.4 1.0 English Fiction 11577 Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech MG 4.7 7.0 English Fiction 17501 Abuela Arthur Dorros LG 2.5 0.5 English Fiction 17602 Across the Wide and Lonesome Prai Kristiana Gregory MG 5.5 4.0 English Fiction 36046 Adaline Falling Star Mary Pope Osborne MG 4.6 4.0 English Fiction 1 Adam of the Road Elizabeth Janet Gray MG 6.5 9.0 English Fiction 301 Addie Across -

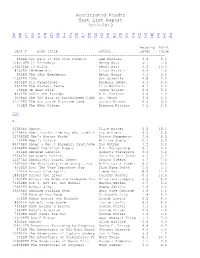

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

Accelerated Reader Test List Report 2012-2013 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Reading Point Test # Book Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 922EN 101 Ways to Bug Your Parents Lee Wardlaw 3.9 5.0 128370EN 11 Birthdays Wendy Mass 4.1 7.0 146272EN 13 Gifts Wendy Mass 4.5 13.0 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Maifair 4.4 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.1 3.0 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 4.8 2.0 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 3.1 2.0 6651EN The 24-Hour Genie Lila McGinnis 4.1 2.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 5.2 5.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. Donahue 4.5 1.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 3.9 1.0 31170EN The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman 4.3 3.0 413EN The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson 4.3 2.0 TOP A 64593EN Abarat Clive Barker 5.5 15.0 61248EN Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved B Kay Winters 3.6 0.5 127685EN Abe's Honest Words Doreen Rappaport 4.9 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 6.2 3.0 86479EN Abner & Me: A Baseball Card Adve Dan Gutman 4.2 5.0 54088EN About the B'nai Bagels E.L. Konigsburg 4.7 5.0 815EN Abraham Lincoln Augusta Stevenson 3.2 3.0 29341EN Abraham's Battle Sara Harrell Banks 5.3 2.0 11577EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7.0 12573EN The Absolutely True Story...How Willo Davis Robert 5.1 6.0 6001EN Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.0 3.0 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 8.9 11.0 18801EN Across the Lines Carolyn Reeder 6.3 10.0 17602EN Across the Wide and Lonesome Pra Kristiana Gregory -

Slavery and Racialized Perspectives in Abolitionist and Neoabolitionist Children’S Literature

Black Girls, White Girls, American Girls: Slavery and Racialized Perspectives in Abolitionist and Neoabolitionist Children’s Literature Brigitte Fielder Tulsa Studies in Women's Literature, Volume 36, Number 2, Fall 2017, pp. 323-352 (Article) Published by The University of Tulsa DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/tsw.2017.0025 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/677145 Access provided by Columbia University (14 Jan 2018 04:20 GMT) Black Girls, White Girls, American Girls: Slavery and Racialized Perspectives in Abolitionist and Neoabolitionist Children’s Literature Brigitte Fielder University of Wisconsin, Madison ABSTRACT: Analyzing abolitionist and neoabolitionist girlhood stories of racial pairing from the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries, this essay shows how children’s literature about interracial friendship represents differently racialized experiences of and responses to slavery. The article presents fiction by women writers such as Harriet Beecher Stowe and Lydia Maria Child alongside Sarah Masters Buckey and Denise Lewis Patrick’s American Girl historical fiction series about Cécile and Marie-Grace in order to show how such literature stages free children’s relationships to slavery through their own racialization. While nineteenth-century abolitionist children’s literature models how to present slavery and racism to free, white children, the American Girl series extends this model to con- sider how African American children’s literature considers black child readers and black children’s specialized knowledge about racism. The model of narration and scripting of reading practices in the Cécile and Marie-Grace stories promote cross-racial identification, showing how, because children read from already racialized perspectives that literature also informs, both black and white children might benefit from seeing alternating perspectives of slavery represented. -

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number

Accelerated Reader Test List Report Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 58255EN 10-Step Guide to Living with You Laura Numeroff 2.3 0.5 35821EN 100th Day Worries Margery Cuyler 3.0 0.5 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Jon Buller 2.5 0.5 523EN 20,000 Leagues under the Sea Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 11592EN 2095 Jon Scieszka 3.8 1.0 30629EN 26 Fairmount Avenue Tomie De Paola 4.4 1.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4.0 9001EN The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubb Dr. Seuss 4.0 1.0 31170EN The 6th Grade Nickname Game Gordon Korman 4.3 3.0 413EN The 89th Kitten Eleanor Nilsson 4.7 2.0 8851EN The A.B.C. Murders Agatha Christie 6.1 9.0 61248EN Abe Lincoln: The Boy Who Loved B Kay Winters 3.6 0.5 101EN Abel's Island William Steig 5.9 3.0 14051EN Abraham Lincoln: 16th President Rebecca Stefoff 8.6 5.0 14903EN Absolute Power David Baldacci 5.8 25.0 11577EN Absolutely Normal Chaos Sharon Creech 4.7 7.0 5251EN An Acceptable Time Madeleine L'Engle 4.5 11.0 5252EN Ace Hits the Big Time Barbara Murphy 4.2 6.0 6001EN Ace: The Very Important Pig Dick King-Smith 5.2 3.0 5253EN The Acorn People Ron Jones 5.6 2.0 21626EN An Acquaintance with Darkness Ann Rinaldi 3.6 10.0 102EN Across Five Aprils Irene Hunt 6.6 10.0 18801EN Across the Lines Carolyn Reeder 6.3 10.0 7201EN Across the Stream Mirra Ginsburg 1.7 0.5 17602EN Across the Wide and Lonesome Pra Kristiana Gregory 5.5 4.0 11701EN -

National African American Read-In

National African American Read-In NCTE Annual Convention attendees were asked to share their favorite book(s) written by an African American author. Africa Dream Eloise Greenfield After Tupac and D Foster Jacqueline Woodson The Amazing Things That Books Can Do Ryan Joiner Another Country James Baldwin Apex Hides the Hurt Colson Whitehead Assata: An Autobiography Assata Shakur The Autobiography of Malcolm X Malcolm X and Alex Haley The Battle of Jericho Sharon Draper Beloved Toni Morrison Black Boy Richard Wright The Bluest Eye Toni Morrison Bronx Masquerade Nikki Grimes Brown Girl Dreaming Jacqueline Woodson Bud, Not Buddy Christopher Paul Curtis Cane Jean Toomer The Collected Poems Lucille Clifton The Color of Water James McBride The Color Purple Alice Walker Copper Sun Sharon Draper The Crossover Kwame Alexander The Devil in Silver Victor LaValle Fences August Wilson The Fire Next Time James Baldwin Giovanni's Room James Baldwin The Grey Album Kevin Young Having Our Say Sarah L. Delany and A. Elizabeth Delany Head Off & Split Nikky Finney The History of White People Nell Irvin Painter I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Maya Angelou Incognegro Mat Johnson The Intuitionist Colson Whitehead Invisible Man Ralph Ellison Jelly Roll Kevin Young Just Mercy Bryan Stevenson Kindred Octavia E. Butler The Legend of Tarik Walter Dean Myers Locomotion Jacqueline Woodson Loving Day Mat Johnson Mama Day Gloria Naylor Meet Addy Connie Porter Of Mules and Men Zora Neale Hurston Out of My Mind Sharon Draper Parable of the Sower Octavia E. Butler Passing Nella