Good Food Battle Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spartan Stores, Inc. Annual Report 2011 Spartan Stores, Inc

SPARTAN STORES, INC. ANNUAL REPORT 2011 SPARTAN STORES, INC. ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Financial Highlights In fi scal 2011 NET SALES ADJUSTED EBITDA OPERATING EARNINGS (IN BILLIONS) (IN MILLIONS) (IN MILLIONS) we focused $108 $73 $2.58 $103 $104 $2.55 $2.53 $2.48 $68 on providing $92 $62 $2.21 $59 consistent $77 $49 excellence across our operations and reducing operating expenses in 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Adjusted EBITDA and total net long term debt are non GAAP financial measures. Please see pages an eff ort to 32-34 of the enclosed form 10-K for a reconciliation. (Dollars in millions, except per share data and percentage data) 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 maximize Net sales $ 2,206 $ 2,477 $ 2,577 $ 2,552 $ 2,533 Gross profit margin 19.6% 20.0% 20.8% 21.9% 22.0% Operating earnings 49 62 73 59 68 profi tability— Net earnings 25 33 37 26 32 Diluted earnings per share 1.16 1.48 1.66 1.14 1.42 Adjusted EBITDA 77 92 108 103 104 and the results Cash from operating activities 59 68 81 92 90 Total net long term debt 97 110 192 176 131 Fiscal years 2011, 2010 and 2007 include impacts of $2.9 million income ($1.8 million net of taxes), prove the sound $6.2 million expense ($4.0 million net of taxes) and $4.5 million expense ($2.9 million net of taxes), respectively, related to restructuring, asset impairment and pension curtailment. -

Protocols* (Local Environment for Activity and Nutrition-- Geographic Information Systems)

LEAN-GIS Protocols* (Local Environment for Activity and Nutrition-- Geographic Information Systems) Version 2.0, December 2010 Edited by Ann Forsyth Contributors (alphabetically): Ann Forsyth, PhD, Environmental Measurement Lead Nicole Larson, Manager, EAT-III Grant Leslie Lytle, PhD, PI, TREC-IDEA and ECHO Grants Nishi Mishra, GIS Research Assistant Version 1 Dianne Neumark-Sztainer PhD, PI, EAT-III Pétra Noble, Research Fellow/Coordinator, Versions 1.3 David Van Riper, GIS Research Fellow Version 1.3/Coordinator Version 2 Assistance from: Ed D’Sousa, GIS Research Assistant Version 1 * A new edition of Environment, Food, and Yourh: GIS Protocols http://www.designforhealth.net/resources/trec.html A Companion Volume to NEAT-GIS Protocols (Neighborhood Environment for Active Travel),Version 5.0, a revised edition of Environment and Physical Activity: GIS Protocols at www.designforhealth.net/GISprotocols.html Contact: www.designforhealth.net/, [email protected] Preparation of this manual was assisted by grants from the National Institutes of Health for the TREC--IDEA, ECHO, and EAT--III projects. This is a work in progress LEAN: GIS Protocols TABLE OF CONTENTS Note NEAT = Companion Neighborhood Environment and Active Transport GIS Protocols, a companion volume 1. CONCEPTUAL ISSUES ............................................................................................................5 1.1. Protocol Purposes and Audiences ........................................................................................5 1.2 Organization of the -

COOL Raises Questions

Just In A record crowd packed the aisles for the AFPD Save the date for S.E. Michigan Holiday Beverage Show! AFPD’s 93rd Annual Trade Dinner and Ball! AFPD's 93rd Annual Trade Dinner and Ball is set for Friday, February 6 2009 and we are heading for the beautiful Shenandoah Country Club in West Bloomfield. This year our theme is “CIRCUS CIRCUS!" Step right up to a night of dining, dancing and a host of carnival activities! Join Michigan and Ohio leaders in the food, beverage and petroleum industries al this one-and-only, industry-wide annual black tie event. We guarantee it will be the “Greatest Show on Earth!" Held September 23 and 24 at Rock Financial Showplace in Novi, a record crowd of over 2,300 attendees were treated to a huge array of new Invitations and detailed sponsorship products, holiday packaged gift sets and show specials. Please see pages 16 and 17 for more photos and details of this event. information will be mailed soon. Information is also available online at wwAAFPDonline.org or call Michele Spartan Stores to acquire VG’s MacWilliams at 1-800-666-6233. Spartan Stores, with headquarters $310 million, and boost overall bring VG’s, a premier Michigan in Grand Rapids, announced that it consolidated sales by $160 million. grocery operator, further into the has agreed to acquire VG’s Food The company expects the Spartan Stores family,” said Craig Center and VG’s Pharmacy, a 17- acquisition to have a neutral effect Sturken, chairman of Spartan, in a Resident’s R e p o rt.................... -

News America Trial Brief

Case 3:04-cv-03500-AET-JJH Document 313 Filed 02/20/2009 Page 1 of 26 HERBERT, VAN NESS, CAYCI & GOODELL A Professional Corporation Steven Goodell, Esq. 22 Chambers Street Princeton, New Jersey 08542 Telephone: (609) 924-2495 Facsimile: (609) 924-8732 MAYER BROWN LLP Lee N. Abrams, Esq. 71 South Wacker Drive Chicago, Illinois 60606 Telephone: (312) 782-0600 Facsimile: (312) 701-7711 REED SMITH LLP Diane Green-Kelly, Esq. 10 S. Wacker Drive Chicago, IL 60606 Telephone: (312) 207-6407 Facsimile: (312) 207-6400 PERKINS COIE LLP Debra Rae Bernard, Esq. 131 South Dearborn, Suite 1700 Chicago, Illinois 60603 Telephone: (312) 324-8559 Facsimile: (312) 324-9559 Counsel for News America Marketing In-Store Services LLC and News America Marketing In-Store LLC FLOORGRAPHICS, INC. UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY Plaintiff, Civil Action No.: 04-3500 (AET) v. Hon. Anne E. Thompson, U.S.D.J. NEWS AMERICA MARKETING IN- Hon. John J. Hughes, U.S.M.J. STORE SERVICES, et al., Defendants. DEFENDANTS’ TRIAL BRIEF Case 3:04-cv-03500-AET-JJH Document 313 Filed 02/20/2009 Page 2 of 26 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 4 KEY ISSUES AT TRIAL .............................................................................................................. 6 A. News America Marketing Expected -

Nws and Wick 2015.Xlsx

PARNELL GENERAL STORE 10391 FIVE MILE ADA MI 49301 (616)691-8511 WOODSTOCK WINE & CHEESE 6409 US 223 ADDISON MI 49220 (517)547-7522 MEIJER #45 217 E US HWY 223 ADRIAN MI 49221 (517)265-7820 ALGONAC WINE & LIQUOR 411 MICHIGAN ST ALGONAC MI 48001 (810)794-1001 PARTY STOP MARKET 7235 ALLEN ALLEN PARK MI 48101 (313)928-7580 MEIJER #233 3565 FAIRLANE BLVD ALLEN PARK MI 48101 (313)253-1100 FAMILY FARE #137 6370 LK MICHIGAN STE 100 ALLENDALE MI 49401 (616)895-6665 CAMPUS PARTY STORE 4814 LAKE MICHIGAN ALLENDALE MI 49401 (616)895-2170 MACKENZIE'S PARTY STORE 7890 ALGER ALMA MI 48801 (989)463-3362 MEIJER #270 2805 W CHEESMAN ALMA MI 48801 (989)576-6100 KOMMUNITY KRACKER BARREL 200 N MAIN ALMONT MI 48003 (810)798-8488 COUNTRY SMOKE HOUSE 3294 VAN DYKE ALMONT MI 48003 (810)798-3064 CAMPAU CORNER 6785 WHITNEYVILLE ALTO MI 49302 (616)868-6845 MEIJER #173 5645 JACKSON ANN ARBOR MI 48103 (734)222-0300 HILLER'S 3615 WASHTENAW AVENUE ANN ARBOR MI 48104 (734)677-2370 STADIUM MARKET 1423 E STADIUM ANN ARBOR MI 48104 (734)761-9650 WOLVERINE PARTY SHOP 2527 DEXTER & MAPLE ANN ARBOR MI 48103 (734)741-4949 THE PRODUCE STATION 1629 S STATE ANN ARBOR MI 48104 (734)663-7848 PLUM MARKET 375 N MAPLE STE 12-19 ANN ARBOR MI 48103 (734)827-5000 WHOLE FOODS MARKET 990 W EISENHOWER PARKWAY ANN ARBOR MI 48104 (734)997-7500 COSTCO #1106 771 AIRPORT ANN ARBOR MI 48108 (734)213-8013 VILLAGE CORNER 1747 PLYMOUTH ANN ARBOR MI 48104 (734)995-1818 A & L WINE SHOPPE 2424 W STADIUM ANN ARBOR MI 48103 (734)665-9463 MEIJER #64 3145 ANN ARBOR SALINE ANN ARBOR MI 48103 (734)769-7800 -

Chain List 2010

2010 PHARMACY CHAIN LIST A E K P S A&P Eaton Apothecary Katy Medical Center Pharmacy P & C Food Market & Pharmacy Stop & Shop Pharmacy Accredo Health Group Econo Foods Pharmacy KD Pharmacy, Inc. Palaca Health Mart Pharmacy Strand Pharmacy Acme Pharmacy Etheckel Pharmacy Kearny Health Mart Pharmacy Pamida Pharmacy Stufflebeon Pharmacy AHS St. John Pharmacy F Kerr Drug Pantry Sun Mart Pharmacy Albertsons Pharmacy Fagen Pharmacy Kessel Pharmacy Pathmark Super 1 Pharmacy Albertsons Sav-on Pharmacy Fairview Pharmacy King Kullen Pavilion Plaza Pharmacy, Inc. Super Fresh Allina Health System Family Fare King Soopers PayLess Drug Stores Super G Discount Drug Appalachian Regional Healthcare Inc Family Meds King's Pharmacy Pediatrics Pharmacy Super Rx Pharmacy Arbor Family Pharmacy Kinney Drugs Pelzel's Hometown Pharmacy Super-D Drug Store Arrow Prescription Center Farm Fresh Pharmacy Kiowa Hometown Pharmacy Pharmacy Center Sweetbay Supermarkets Aurora Pharmacy Farmacia Plaza Klein's Family Pharmacy Pharmerica T B Felpausch Pharmacy Klingensmith's Drug Store Pick N Save Target B&B Pharmacy Food 4 Less KLM Pharmacy, Inc. Piggly Wiggly Pharmacy Thrifty White Pharmacy Baker's Food City Pharmacy Kmart Pharmacy Powell Prescription Center Tiffany's Drug Baptist Pharmacy Food City United Drug Knight Drugs, Inc. Prairie Stone Pharmacy Times Pharmacy Bartell Drugs Food Lion Pharmacy Kroger Price Chopper Pharmacy Times Supermarket Bashas United Drug Food Pyramid L Price Cutter Pharmacy Tom Thumb Bel Air Pharmacy Food World Lewis Drug Price Wise Pharmacy Top Food & Drug Bi-Lo Foods Fred Meyer Lifechek Drug Professional Pharmacy Services Tower Pharmacy Bi-Lo, LLC Fred's Pharmacy Livingston Medical Pharmacy Publix Super Markets, Inc. -

Ready to Take on U.S. RETAIL MARKET the No.1 Player in the U.K

inside... The Pundit Looks At Tesco • OCEAN SPRAY’S LAWSUIT • Canadian Retailers • Tie-Ins • Refrigerated Juice • Pictures From Mexico Regional Profile: Chicago • Fruit Ripening • Latino Consumers • South African Citrus • Fresh Herbs • Organic Fruit • CHERRIES MANGOS • MELON MERCHANDISING • Stone Fruit • Portable Dried Fruit Snacks • Exotic Plants and Flowers MAY 2007 • VOL. 23 • NO. 5 • $9.90 MARKETING • MERCHANDISING • MANAGEMENT • PROCUREMENT TESCO Ready To Take On U.S. RETAIL MARKET The No.1 player in the U.K. retail world is set to launch a major U.S. venture. © 2006 Reader Service # 13 MAY 2007 • VOL. 23 • NO. 5 FEATURES 94 OCEAN SPRAY SUED BY LONGTIME ASSOCIATES . 32 Lawsuit alleges special deals for Costco, H.E. Butt at the expense of Sam’s Club, B.J.’s, and others. Cover photos courtesy of THE CANADIAN RETAIL ENVIRONMENT . 42 Fresh Produce Journal Responding to a diverse and demanding public reveals these supermarkets staying flexible and tuned-in to their customers. COVER STORY TIE-INS PROVIDE INNOVATIVE WAYS TO MOVE PRODUCE . 50 TESCO READY TO TAKE ON Consumers looking for novelty and convenience are U.S. RETAIL MARKET . 18 the target audience for a wide variety of add-on items. The No.1 player in the U.K. retail world is set to launch a major U.S. venture. INDUSTRY POLL: WHAT’S IN STORE FOR THE REFRIGERATED JUICE CATEGORY?. 54 Industry leaders discuss the future of this rapidly expanding category. COMMENTARY DEPARTMENTS OF AGRICULTURE PROMOTE THE INDUSTRY (PART 1) . 75 THE FRUITS OF THOUGHT A sampling of these state agencies shows them as powerful produce industry advocates. -

Spartan Stores 2010 Annual Report

850 76TH STREET SW | PO BOX 8700 | GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN 49518 www.spartanstores.com SPARTAN STORES ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Spartan AR 10 Final.indd 2 6/15/2010 9:15:19 AM SPARTAN STORES ANNUAL REPORT 2010 Company Profile During fiscal 2010, Spartan Stores, Inc. and Subsidiaries our retail and distribution 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 Stores 96 100 99 87 73 businesses generated Fuel Stations 24 19 16 10 6 a combined operating Pharmacies 68 66 51 42 40 Stores serviced by Distribution 358 372 393 408 443 $ profit of 59 million, Private label items 3,114 2,822 2,442 3,000 2,751 and, for only the second Financial Highlights time in our public Spartan Stores, Inc. and Subsidiaries The results of discontinued operations are not reflected in the operating data below. Adjusted EBITDA is a non-GAAP financial measure. Please company history, achieved see page 32 of the enclosed form 10-K for a reconciliation. (In millions except per share data, percentage data and ratio). $ over 100 million in 2010 2009 2008 2007 2006 Adjusted Earnings Before Net sales $2,552 $2,577 $2,477 $2,206 $1,873 Gross margin $559 $536 $495 $431 $345 Interest, Taxes, Depreciation Gross margin percentage 21.9% 20.8% 20.0% 19.6% 18.4% (EBITDA) Adjusted EBITDA $103 $108 $92 $77 $57 & Amortization . Adjusted EBITDA percentage 4.0% 4.2% 3.7% 3.5% 3.0% These financial measures Operating earnings* $59 $73 $62 $49 $34 Operating earnings percentage 2.3% 2.8% 2.5% 2.2% 1.8% are just a few of the many Net earnings* $26 $37 $33 $25 $18 ways that we gauge our Net earnings percent of net sales 1.0% 1.4% 1.3% 1.1% 1.0% Diluted earnings per share* $1.14 $1.66 $1.48 $1.16 $0.86 success. -

Your Benefits Card Merchant List

Your Benefits Card Merchant List ¾ Use your benefits card at these stores that can identify FSA/HRA eligible expenses. ¾ Check the list to find your store before you order prescriptions or shop for over-the- counter (OTC) items. ¾ Swipe your benefits card first and only your FSA/HRA eligible purchases will be deducted from your account. ¾ You won’t have to submit receipts to verify purchases from these stores, but you should still save your receipts for easy reference. ¾ Merchants have the option of accepting MasterCard and/or Visa for payment. Before making a purchase with your benefits card, please make sure you know which cards are accepted. Ist America Prescription Drugs* Albertville Discount Pharmacy* AmiCare Pharmacy Inc* 3C Healthcare Inc, dba Medicap Alden Pharmacy* Anderson and Haile Drug Store* Pharmacy* Alert Pharmacy Services-Mt Anderson County Discount 50 Plus Pharmacy* Holly* Pharmacy* A & P* Alexandria Drugs Inc* Anderson Drug-Athens TX* Aasen Drug* Alfor’s Pharmacy* Anderson Pharmacy-Denver PA Abeldt’s Gaslight Pharmacy* Allcare Pharmacy* Anderson Pharmacy/John M* ACME * Allen Drug* Anderson’s Pharmacy* Acres Market (UT) * Allen’s Discount Pharmacy* Andrews Pharmacy* Acton Pharmacy Allen Family Drug* Anthony Brown Pharmacy Inc* Adams Pharmacy* Allen’s Foodmart* Antwerp Pharmacy* Adams Pharmacy Inc* Allen’s of Hastings, Inc.* Apotek Inc. Adams Pharmacy and Home Allen's Super Save #1 Provo Apotek Pharmacy* Care* UT* Apoteka Compounding LLC* Adamsville Pharmacy* Allen's Super Save #2 Orem UT* Apothecare Pharmacy* Adrien Pharmacy* -

COVE Alliance Gift Card List 2010

COVE Alliance Gift Card List 2010 "346" Brooks Brothers $25.00 (16%) J. Crew $25.00 (13%) 1913 Room $25.00 (5%) J. Jill $25.00 (8%) 77kids $25.00 (10%) Jack in the Box $10.00 (4%) 84 East Pasta Etc $25.00 (5%) Jamba Juice $10.00 (7.00%) 8th Street Grille $25.00 (5%) James Street Inn $25.00 (5%) 99 Restaurants $25.00 (13%) JCPenney $25.00 (5%) A Pea in the Pod $25.00 (8%) JCPenney $100.00 (5%) A&P Food Stores $25.00 (4%) Jean Louis David $25.00 (8%) A&P Food Stores $100.00 (4%) Jewel-Osco $25.00 (4%) Acapulco Mexican Restaurant y Cantina $25.00 (9%) Jewel-Osco $100.00 (4%) Ace Hardware $25.00 (4%) Jiffy Lube $30.00 (8%) Ace Hardware $100.00 (4%) Jo-Ann Fabrics $20.00 (6%) Acme (DE, MD, NJ and PA only) $25.00 (4%) Joe's Seafood Prime Steak & Stone Crab $25.00 (12%) Acme (DE, MD, NJ and PA only) $100.00 (4%) Jolly Trolley Bar & Grill $25.00 (8%) Advance Auto Parts $25.00 (7.00%) Journeys $25.00 (10%) aerie $25.00 (10%) Journeys Kidz $25.00 (10%) Aeropostale $25.00 (7.00%) JW Marriott Hotels $50.00 (8%) AJWright $25.00 (7.00%) JW Marriott Hotels $100.00 (8%) $100.00 AJWright (7.00%) JW Marriott Hotels $500.00 (8%) Albertsons $25.00 (4%) Kay Jewelers $50.00 (6%) Albertsons $100.00 (4%) Kemah Boardwalk $25.00 (9%) Allied Waste (W. MI only) $20.00 (10%) Kemah Boardwalk $100.00 (9%) Allied Waste (W. -

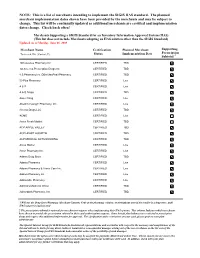

This Is a List of Merchants Intending to Implement the SIGIS IIAS Standard

NOTE: This is a list of merchants intending to implement the SIGIS IIAS standard. The planned merchant implementation dates shown have been provided by the merchants and may be subject to change. This list will be continually updated as additional merchants are certified and implementation dates change. Check back often! Merchants Supporting a SIGIS Standard for an Inventory Information Approval System (IIAS) (This list does not include Merchants adopting an IIAS solution other than the SIGIS Standard) Updated As of Monday, June 01, 2009 Merchant Name Certification Planned Merchant Supporting Prescription To Search: Hit: (Control; F) Status Implementation Date Subtotal 2 16th Avenue Pharmacy Inc CERTIFIED TBD 1st America Prescription Drugs Inc CERTIFIED TBD 4 S Pharmacy Inc. DBA MacPhail Pharmacy CERTIFIED TBD 50 Plus Pharmacy CERTIFIED Live A & P CERTIFIED Live A & S Drugs CERTIFIED TBD Aasen Drug CERTIFIED Live Abeldt's Gaslight Pharmacy, Inc CERTIFIED Live Access Drugs LLC CERTIFIED TBD ACME CERTIFIED Live Acme Fresh Market CERTIFIED TBD ACP APPLE VALLEY CERTIFIED TBD ACP HEART HOSPITAL CERTIFIED TBD ACP MEDICAL ARTS BUILDING CERTIFIED TBD Acres Market CERTIFIED Live Acton Pharmacy Inc. CERTIFIED Live Adams Drug Store CERTIFIED TBD Adams Pharmacy CERTIFIED Live Adams Pharmacy & Home Care Inc. CERTIFIED Live Adams Pharmacy Inc CERTIFIED Live Adamsville Pharmacy CERTIFIED Live Adcock's Medicine Chest CERTIFIED TBD Adirondack Pharmacy, Inc. CERTIFIED TBD 1 Will use the Drug Store/Pharmacy Merchant Category Code at the pharmacy window, or throughout store if the retailer is a drug store, until IIAS support is implemented 2 The prescription subtotal is optional for merchants to support when implementing their IIAS systems. -

Food Basics' Advertising Questioned

Vol. 15, No. 6 PORT The official publication of the Associated Food Dealers of Michigan June 2004 Food Basics’ Advertising Questioned By Michele MacWilliams Four of O’Brien’s Amid much fanfare, on Tuesday products that March 30, The Great Atlantic & were listed in Pacific Tea Company (A&P, NYSE: Food Basics’ GAP) opened 10 every-day-low- circular were price Food Basics grocery stores mispriced and throughout Metro Detroit giving additional items away a $70 store gift certificate on store signs in every hour. The $70 was significant Food Basics because A&P officials maintain that carried incorrect $70 buys the same amount of information groceries that $ 100 buys at a about O'Brien’s, conventional supermarket. according to Their claim may or may not be Yono. true. According to a competing In the sample retailer, information that Food Basics shopping cart list included in their sale circulars and on their signs is misleading and - in Food Basics, some cases - just plain untrue. continued on Munim Yono, owner of O'Brien’s page 12. Supermarket in Ecorse, was outraged to find that Food Basics had compared a sample shopping cart of House Defeats Tobacco Tax Hike - For Now food at his store, and the local Due in large part to intense lobbying by AFD and our coalition, on Kroger to Food Basics. All shopping Wednesday, May 19, the Michigan House of Representatives rejected Bead howAFD’s Board helps you .. 3 took place on March 17, 2004. Governor Granholm’s proposed 75-cent per pack cigarette tax hike, which However, Food Basics didn’t open Court dismisses unwholesome would have increased the tax to $2 per pack.