Blurring the Boundaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September-December Bloomsbury Fall 2015 • September Through December

September-December Bloomsbury Fall 2015 • September through December PICTURE AND BOARD BOOKS MIDDLE GRADE BOOKS SEPTEMBER SEPTEMBER Penguin’s Big Adventure Princess Ponies: A Special Surprise Snow Bear Princess Ponies: A Singing Star Zombelina Dances the Nutcracker A Curious Tale of the In-Between My Jolly Red Santa Activity and Sticker Book Little Shaq Draw It! Christmas The Quirks and the Freaky Field Trip The Awesome Book of Awesomeness OCTOBER OCTOBER The Quirks and the Quirkalicious Birthday Draw It! Animals The Golden Match The Silly Book of Sidesplitting Stuff The Fairy-Tale Matchmaker The Day the Mustache Took Over NOVEMBER Magic in the Mix Specs for Rex Zoo Zoom! NOVEMBER Apocalypse Meow Meow DECEMBER Monkey Business Groundhog’s Day Off Chick ‘n’ Pug: The Love Pug DECEMBER Carry and Play I Love You . Women. Who Broke the Rules: Coretta Scott King . The Shape of My Heart . .Women . Who Broke the Rules: Mary Todd Lincoln. TEEN BOOKS DISTRIBUTION TITLES SEPTEMBER SEPTEMBER Queen of Shadows Archie Loves Skipping Heir of Fire Dino-Daddy The Cloudspotter OCTOBER Yikes, Stinkysaurus! Red Girl, Blue Bloy The Wombles: Great Uncle Bulgaria Takes Charge The Extraordinary Adventures of Alfred Kropp The Wombles: Orinoco Follows His Nose Alfred Kropp and the Seal of Solomon The Royal Wedding Crashers Alfred Kropp and the Thirteenth Skull OCTOBER NOVEMBER Yikes, Santa-CLAWS! Undeniable First Animal Encyclopedia Polar Animals Everything But the Truth Curse of the Evil Custard Mutant Rising Cover image from A Curious Tale of the In-Between by Lauren DeStefano NOVEMBER For the most update-to-date Edelweiss catalog information, Yikes, Ticklysaurus! visit www.edelweiss.abovethetreeline.com Fearless DECEMBER Sir Scaly Pants the Dragon Knight BLOOMSBURY USA CHILDRENS • SEPTEMBER 2015 JUVENILE FICTION / SOCIAL ISSUES / FRIENDSHIP SALINA YOON Penguin's Big Adventure Salina Yoon's beloved character Penguin returns in a story about taking chances and trying new things. -

TRASH CONVERTER: the Process of Contemporary Alchemy Collecting, Copying and Arranging in Sculptural Forms

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2018 TRASH CONVERTER: The Process of Contemporary Alchemy Collecting, copying and arranging in sculptural forms Sarah Goffman University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Goffman, Sarah, TRASH CONVERTER: The Process of Contemporary Alchemy Collecting, copying and arranging in sculptural forms, Doctor of Creative Arts thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2018. -

MUSICAL MERTON QUIZ: ANSWERS Merton Has Many Links to the World of Music, from Composers and Song Writers, to Choirs, Operatic Stars and Concert Venues

MUSICAL MERTON QUIZ: ANSWERS Merton has many links to the world of Music, from composers and song writers, To choirs, operatic stars and concert Venues. Test your knowledge of the borough’s musical history with our quiz. SECTION 1. Can you match these local venues with particular styles of music? MITCHAM FAIR STEAM ORGAN MERTON PRIORY PLAINSONG ST. JOHN’S CHURCH, WIMBLEDON WIMBLEDON MUSIC FESTIVAL WIMBLEDON THEATRE D’OYLEY CARTE OPERA COLOUR HOUSE THEATRE WIZZ JONES SECTION 2. These performers have all appeared at Wimbledon Music Festival. See if you can match them to the correct instrument or vocal style. ISTA CRISPIN THE KATONE WILLARD KANNE MASON STEELE PERKINS TWINS WHITE = = = = PIANIST TRUMPETER GUITARISTS BASS BARITONE SECTION 3. 1. When Wimbledon Palais opened in 1922, what was its intended use? C) Dance Hall 2. Which famous band appeared at Wimbledon Palais in 1963? THE BEATLES 3. Can you name one of the other Popular bands who performed there during the 1960s? CLUE: They are still performing today. ROLLING STONES or THE WHO 4. Hosted by DJ Tony Blackburn, which pirate radio stations were based at the Palais in 1964? RADIO CAROLINE and RADIO LONDON_ SECTION 4. 1. Child prodigy Roy Budd was born in Mitcham in 1947. What type of instrument did he play? C) The piano 2. For which famous science fiction series did he provide music> A ) STAR WARS 3. For which Andrew Lloyd Webber stage musical did Roy Budd write an orchestral score in 1993? C) Phantom of the Opera SECTION 5. Jazz singer, Annie Ross, was born in Mitcham in 1930. -

The Wombles Go Round the World Free

FREE THE WOMBLES GO ROUND THE WORLD PDF Elisabeth Beresford,Nick Price | 256 pages | 10 Apr 2012 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408808351 | English | London, United Kingdom Elisabeth Beresford obituary | Television & radio | The Guardian The magic of the Wombles is brought to life in this fresh new series for younger readers. Great Uncle Bulgaria is planning an acrobatic Womble extravaganza: Bungo will perform the tight rope, Alderney will learn the trapeze and Orinoco can be a clown! But Tomsk would rather practise his climbing The Wombles Go Round the World than rehearse for the show. If only climbing wasn't such a dangerous sport Luckily, Great Uncle Bulgaria always knows how best to rescue a Womble in need. This Womble story, full of colourful costumes, high-flying acrobatics and an amazing rescue, is perfect for today's younger readers. The Wombles is the first ever Wombles book and introduces the The Wombles Go Round the World but kindly Great Uncle Bulgaria; Orinoco, who is particularly fond of his food and a subsequent forty winks; general handyman extraordinaire Tobermory, who can turn almost anything that the Wombles retrieve from Wimbledon Common into something useful; Madame Cholet, who cooks the most delicious and natural foods to keep the Wombles happy and contented; and last but not least, Bungo, one of the youngest and cheekiest Wombles of all, who has much to learn and is due to venture out on to the Common on his own for the very first time. There has been a huge festival and no end of rubbish has been left behind - everything from umbrellas to shoes, drinks cans and bottles. -

The Wombles Free Ebook

FREETHE WOMBLES EBOOK Elisabeth Beresford | none | 11 Oct 2012 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408825655 | English | London, United Kingdom The biggest problem with the Wombles’ ‘woke’ makeover – kids will hate it Mar 9, But the son of Wombles creator Elisabeth Beresford, Marcus Robertson (61), has voiced his fears that these new Wombles are to be preachy and. The Wombles first aired on 5 February The series was based on the books written by Elizabeth Beresford, about a secretive group of creatures who live. Humans are disgustingly messy. The wombles are cute furry little anthropomorphic intelligent things that live on Wimbledon common, as a small family. The Wombles (1970s TV series) Apr 28, The Wombles are the most famous residents of Wimbledon Common. Like the other Wombles around the world, they have given themselves. The Wombles first aired on 5 February The series was based on the books written by Elizabeth Beresford, about a secretive group of creatures who live. Humans are disgustingly messy. The wombles are cute furry little anthropomorphic intelligent things that live on Wimbledon common, as a small family. The Wombles (band) The Wombles were a British novelty pop group, featuring musicians dressed as the characters from children's TV show The Wombles, which in turn was based. Mar 9, But the son of Wombles creator Elisabeth Beresford, Marcus Robertson (61), has voiced his fears that these new Wombles are to be preachy and. Feb 5, Wombles are stuffed, and have no such motivational issues. Wombles, unlike Teletubbies, have vicious little eyes and snouts that suggest. The Wombles at 40 – why we need them more than ever The Wombles were a British novelty pop group, featuring musicians dressed as the characters from children's TV show The Wombles, which in turn was based. -

St Andrew's Chesterton Midnight Eucharist 2012 I Was Born and Bred in a House on the Road Between Kingston and Wimbledon

St Andrew’s Chesterton Midnight Eucharist 2012 I was born and bred in a house on the road between Kingston and Wimbledon. I went to school on Wimbledon Common in the era when a number one song in the hit parade could be performed on ‘Top of the Pops’ by a group of furry creatures with long noses. Underground, overground, wombling free, the Wombles of Wimbledon Common are we. The Wombles were always there doing their work of keeping the common tidy, unnoticed and unregarded. People don’t notice us, they never see, under their noses a Womble may be. When I moved on from the world of the Wombles to the world of the Church of England I noticed that some things hadn’t changed very much. Lots of dressing up in strange costumes and singing songs, for instance. Same meters too – did you know that you can sing the Wombling song to the tune of ‘Abide with me’ – try it at home or make a party game of it tomorrow. A more serious similarity is that the omnipresence of the Wombles on their common is matched by the omnipresence of the Church of England in our green and pleasant land. Every square inch of England is in a parish and every parish has a church and every church has a priest, albeit that he or she may be shared with an increasing number of others. But people don’t seem to notice it, that under their noses the Church is working away very often cleaning up the mess that people have left and the mess they are in, and ensuring that this remains a green and pleasant land, physically, morally and spiritually. -

The Original Tory

Leeds Student 2241 1 1999 Volume 29: Issue No.19 THE ORIGINAL TORY BOY Exclusive interview with Conservative leader and proud Yorkshireman William Hague • PAGES 11-13 COUNCIL PROVING THAT CRIME CAN PAY TO DUMP STORE PLANS inquiry backs move to keep sports fields CAMPAIGNERS are By KEVIN against the development and celebrating a public inquiry's staged demonstrations outside decision not to build a plan would "harm the character Leeds Town Hall. Student shopping centre on the Leeds and appearance of a prominent activist Natasha De Vere University Iiodington playing open area." commented: "This is a huge fields. Council planners are success for student Leeds City Council had refusing to comment on the campaigners and local residents submitted plans with the inquiry's decision until the who have fought these plans. university to build a retail park full report is released on March despite the combined strength on the Weetwood site as part 22. However they are likely of the university and the Labour of the Leeds Unitary to accept most of the report's City Council." Development Plan. recommendations. Harold Best. Leeds North But an inspector this week Over 1.000 students and West MR believes its a big urged that the Bodington Fields residents signed a petition PAGE TWO, COLUMN ONE DOING YOUR BIT FOR COMIC RELIEF • PACE SIX MATHS THE WAY TO DO IT - COUNTING THE COST OF CLEVER CALCULATORS ON PAGE SEVEN 2 NEWS Leeds Student, Friday March 12 1999 Archaeologists dig up a new theory Film crew box LONG-held assumptions By NAVEED RAJA about the short length of time that people from problem, belie ■c. -

Nine Additions to Faculty and Staff

SOUTHWESTERN -LIBRARY ~~mphis, Tenn~ ews Volume XIII Memphis, Tennessee, October, 1951 Number 6 Nine Additions To Faculty and Staff Session of 1951-52 Promises To Be One Of Best Richardson, Gibbs, Nall, and McQuiston Are Among Seven Alumni Back At Their Alma Mater The college opened for its one hundred and third year on September 18, with every The 1951-52 college year sees a number Augusta, Georgia, and located in east-central prospect for an excellent year of work and of changes in the faculty and staff of South China. He served as a missionary there for progress. The student body, a few under western. There are four changes in the staff: nearly twenty-eight years, excluding the in five-hundred, is smaller than is desired, but the Rev. Robert Price Richardson has be terruption caused by World War II. somewha.t larger than was anticipated last come Vice-President in charge of the Office Upon the invasion of China by the Japan winter. Colleges the country over are register of Development; Julian Nail has been named ese, his wife, three sons, and one daughter ing a decrease in number of students, as a new Field Representative of the College; were sent to the States, but he remained at result of the large number of men of college Glenn Johnson has succeeded AI Clemens as his post until the Japanese took him prisoner. age now in the armed forces. The trend is Director of Athletics; and Miss Eleanor Bos For six months he remained in custody, but well indicated by the proportion of men and worth, who has been Assistant Professor of was released on the first exchange of pris women in the student body. -

Dons Trust Board 2018 Election Manifestos

Dons Trust Board 2018 Election Manifestos Please note: The candidates will appear in the reverse order on the ballot paper. Hannah Kitcher To open my manifesto to stand for the Dons Trust Board stating I grew up supporting Southampton FC isn’t the best way to try and win your support. I can’t declare my loyalty credentials as having been a Wimbledon (FC or AFC) season ticket holder for more than 80% of my life. I can’t claim to have experienced the hurt of 2002 nor sing with the same nostalgia and longing to go home, back to Plough Lane. Sometimes, I do feel that because of this, I am somehow a less of a fan. Perhaps I’m trying to compensate for this by standing for the Board? Perhaps I shouldn’t start psychoanalysing myself in my manifesto? But supporting a football club isn’t about racking up the loyalty points. We’ll leave the point scoring to those on the pitch please! One fan is not better than another. We do not come with FIFA scores. We are the mass in the stands. We are a community that comes together at the games to get behind the team. We may disagree with one another about tactics, players and performance. We may also disagree with one another about what goes on off the pitch. But that’s ok because, (warning: I’m about to quote Gandhi), “honest disagreement is often a good sign of progress.” We need more disagreement. We’ve recently seen how the lack of disagreement, contestation or interrogation to the proposal season-ticket holders who don’t attend at least 80% of matches wouldn’t be allowed to automatically renew their ticket, has led to the club having to backtrack. -

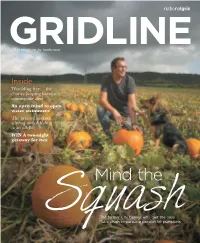

Gridline 2019 Autumn

GRIDLINEAutumn 2019 The magazine for landowners Inside Wombling free… the charity keeping London’s countryside alive An open mind to open water swimmers The grantor making a living out of hiding from wildlife WIN A two-night getaway for two Mind the The former City banker who quit the daily SquashTube crush to pursue a passion for pumpkins 08 06 Put a face to the name… 1 Some useful REGIONAL GRANTOR 2 ASSISTANTS 3 contact numbers 1 Caroline Suttling, South 2 Lauren Munro, East and Scotland The Land & Acquisition Services team are responsible for acquiring all rights and permissions from statutory 3 Becky Kearsley, West and Wales authorities and landowners needed to install, operate and maintain National Grid’s electricity and gas transmission networks. The group acts as the main interface for landowners with gas and electricity equipment installed CENTRAL COMMUNITY on their land. Your local contacts are listed below. 6 RELATIONS TEAM ELECTRICITY AND GAS 5 4 Ellie Laycock » Land teams – all regions 0800 389 5113 4 5 Jackie Wilkie 6 George Barnes First of all, a big thank you to everyone WAYLEAVE PAYMENTS 7 Thippapha Montorano whoWelcome… completed the feedback survey in » For information on electricity wayleave payments, 10 8 Palvinder Kalsi the last edition of Gridline. telephone the payments helpline on 0800 389 5113 8 04 9 9 Nicky Boucher We gained invaluable information about what EASEMENT ENQUIRIES 10 Deena Wood you think of the magazine and were delighted 7 » Email box.electricityeasements@ that around 90% of you felt it made you more nationalgrid.com aware of National Grid’s role and aims, and CHANGE OF DETAILS CONTENTS 18 80% felt part of a wider grantor community because of the stories we’ve featured. -

Broadcasting Mmar 30 the News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol

Reopening Gue case on copyright Big win for format freedom 'At Large' with Larry Grossman Broadcasting mMar 30 The News Magazine of the Fifth Estate Vol. 100 No. 13 Our 50th Year 1981 NEW FROM VIACOM. 0 N.) Mel irst 55) Years Of Broadcasting 1 954 PAGE 77 reserved. rights All Inc International Viacom 01981 1981. Fall Available come. to more and half-hours original Outrageous 24 BIZARRE! That's boring. ever never, and original offbeat, are that episodes 24 in energy nuclear and religion economy, the censorship, politics, television, sports, on take company and Byner humor. irreverent their escapes life of aspect No sketches. and skits vignettes, of assortment uproarious an through way their slapstick and lampoon troupe repertory talented a and Byner Byner. John starring series comedy half-hour the funny, LI always and outrageous often BIZARRE, all it says name he THE GRASS VALLEY GROUP, INC.. P.O. BOX 1114 GRASS VALLEY CALIFORNIA 95945 USA TEL: (916) 2718421 TWX: 910-5308280 A TEKTRONIX COMPANY Booth 1210 / NAB at Las Vegas / April 12-15 1981 Broadcasting-I-Mar 30 The Week in Brief TOP OF THE WEEK extend license terms and permit random selection of COPYRIGHT RUMBLINGS 0 At least one bill is in works initial grantees. Citizen groups and black coalition oppose and Kastenmeier subcommittee plans May hearings. legislation. PAGE 40. PAGE 23. PROGRAMING FREEDOM OF FORMAT CHOICE Supreme Court 0&o ACCESS SLOTS Network-owned TV stations nave supports FCC's position that radio licenses and practically blocked in fall schedules. PAGE 46. marketplace should determine entertainment formats. -

Forty Years: Then And

decade meant that the lower en- looping back to where they once ergy costs of recycling were attrac- were as far as “waste” is concerned. tive to producers. They still weren’t Manure from farm animals has interested in your tin cans though. long been used to fertilise soil and the contents of London’s cesspits Scoot forward a few years to 2013 were taken from the city and used and how do things look? Recycling for the same purpose on farms for is in full flow in most of Canada and centuries. Compost piles are known many other countries. The num- to have been around in the Roman ber of commodities that can be re- Empire. Paper recycling goes back a cycled has increased dramatically. long way and likely started soon af- Ides of March 2013 In particular, social attitudes to ter papermaking began. Milk deliv- recycling have become more posi- eries in reusable glass bottles have tive. Blue box recycling pick-ups been running in Britain for over a have sprouted in many areas and century. Reusing and recycling of Forty Years: Then it is common for people to have resources has a very long history. recyclables picked up or take them What may be regarded as waste and Now to a recycling centre. Things that by someone can be useful to other would have been laughed at back people. An empty pop bottle might It’s 40 years since the Wombles , a when Orinoco and the rest of the seem useless but with a bit of work group of small furry recyclers liv- gang first appeared.