INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tornado Can't Defeat Spirit of West Liberty

THE STATE JOURNAL n FRANKFORT, KENTUCKY n mRCH A 11, 2012 n PAGE D3 Tornado can’t defeat spirit of West Liberty ust when man believes them again before the sun rose homes that once stood on those so vivid that I felt like I was living he has gained some con- the next day. shady hills in Morgan County. there with them in that little log trol, amassed some power, My grandfather moved his They waded in the creek where my house or playing in the yard with JMother Nature quickly puts family in the 1920s to Ashland grandmother had drawn water, the children. Though I am sure him in his place as she did re- where he used his talent as a car- and they found a tree with the ini- they had hardships, they focused cently through the tornadoes that penter to help construct what was tials JLE, ones my grandfather had only on the good times, those pounded our area. Particularly once called Armco Steel Corpora- carved there decades before. hard hit was West Liberty, a town tion. My mother recalled the day My grandfather was actually memories of a loving family in a which, although I have never lived the family boarded the train in one of the most intelligent hu- world that now seems so far away. there, still holds a special place in West Liberty, saying goodbye to man beings I have ever known, Yes, the storm took its toll, my heart, for it is the birthplace Nancy Farley grandparents, aunts, uncles and not to mention a man of great hu- demonstrating to us once again of my maternal grandparents, STATE JOURNAL COLUmNIST cousins, making what seemed mor and wit. -

The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 12-15-2020 The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Gideon Reuveni University of Sussex Diana University Franklin University of Sussex Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Reuveni, Gideon, and Diana Franklin, The Future of the German-Jewish Past: Memory and the Question of Antisemitism. (2021). Purdue University Press. (Knowledge Unlatched Open Access Edition.) This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST THE FUTURE OF THE GERMAN-JEWISH PAST Memory and the Question of Antisemitism Edited by IDEON EUVENI AND G R DIANA FRANKLIN PURDUE UNIVERSITY PRESS | WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA Copyright 2021 by Purdue University. Printed in the United States of America. Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file at the Library of Congress. Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-711-9 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of librar- ies working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-1-61249-703-7. Cover artwork: Painting by Arnold Daghani from What a Nice World, vol. 1, 185. The work is held in the University of Sussex Special Collections at The Keep, Arnold Daghani Collection, SxMs113/2/90. -

Sometimes Shocking but Always Hilarious

The Sound of Hammers Must Never Cease: The Collected Short Stories of Tim Fulmer Party Crasher Press ©2009, 2010, 2014, Tim Fulmer. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Tim Fulmer. This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental and perhaps the result of a psychotic breakdown on the reader’s part. This definitive collection of Tim Fulmer’s highly entertaining short work includes an introduction by the author and sixty-one stories that chronicle the restless lives of what have been called Gen X and Gen Y. From the psychotic disillusionment of inner city life in “Chicago, Sir" and “Mogz & Peeting” to the shocking and disturbing discoveries of suburban dysfunction in “It’s Pleonexia” and “Yankee Sierra,” Tim Fulmer tells us everything we need to know about growing up and living in North America after 1967. His characters are very scary people -- people with too much education, too much time on their hands, and too much insight ever to hold down a real job long enough to buy a house and support a family -- in short, people just like how you and I ought to be all the time. These are stories of concealed poets, enemies of the people, awful bony hands, pink pills, sharp inner pains, Jersey barriers, and exquisite corpses. The language throughout is unadorned, accurate, highly crafted, ecstatic, even grammatically desperate. -

Demons That Resist Exorcism Second Generation Perspectives Barbara Dorrity P 15

m "^ n Volume UII No. 10 October 1998 £3 (to non-members) Don't miss... Gombrich's blotting paper Refleaions on the deformed nationalism of parts of Europe Richard Grunberger P3 Carl Sternheim Dr Anthony GrenviHe p5 Demons that resist exorcism Second generation perspectives Barbara Dorrity p 15 ationalism is a force with a gut appeal long awaits canonisation - for his opposition to Tito's Russian underestimated by Liberals and Marxists atheist communism. N alike. However, not every manifestation of And in Brussels, the political heart of Europe, a enigma it was necessarily malignant. Flemish nationalist deputy has laid a Bill before the aifa When the French invented la patrie they also Belgian parliament to compensate erstwhile collabo century ago, Ls.sued a universal Declaration of the Rights of Man. rators for punishments meted out to them after HChurchill Italian unification was inspired by Mazzini's lib Liberation. In extenuation of their wartime conduct described Russia as eralism. In our own lifetime Catalans and Basques he conjures up a prewar spectre of Flemings as a riddle wrapped fought against Franco. .second-class citizens chafing under the misrule of a up in an enigma. Nonetheless, in the la.st war the Axis powers were French-speaking elite. The observation still immeasurably helped by the slights - real or imagi There may be a grain of truth in this - but to holds good today. nary - that had been inflicted on national groups in argue that exposure to relative discrimination justi An example is Eastern Europe. In consequence, Slovaks and Croats antisemitism which fied collaborating with occupiers who wiped out caused every third actively helped to effect the breakup of Czecho Belgian independence and practised total discrimi Jew to leave in the slovakia and Yugoslavia respectively. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Finding

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, photographs, books, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2017 Quantity: 12.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: • magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations, etc. • program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules • industry publications • national news clippings • awards program catalogs • network communications, and • camera-ready advertising copy • television production photographs Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/22/2019 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: • Bob Hope • Johnny Carson • Jay Leno • Conan O’Brien • Jimmy Fallon • Disney • Motown • The Emmy Awards • Seinfeld • Saturday Night Live (SNL) • Carson Daly • The Mike Douglas Show • Kennedy & Co. • AM America • Miami University Studio 14 Nineteen original Seinfeld scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Notably, the original pilot scripts are included, which indicate that the original title ideas for the show were Stand Up, and later The Seinfeld Chronicles. -

Program Guide Report

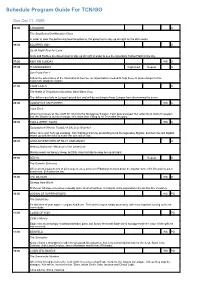

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Oct 11, 2009 06:00 CHOWDER G The Sing Beans/Certifrycation Class In order to cook the performing food Sing Beans, the gang has to stay up all night as the dish cooks. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY G Up All Night/ Pool For Love Andy and Rodney are determined to stay up all night in order to see the legendary Yellow Flash in the sky. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G 07:05 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Sun Probe Part 1 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO G The Battle of Pimpleback Mountain/ Dead Bean Drop The Jellies rip a hole in Lumpus' prized tent and will do anything to keep Lumpus from discovering the secret. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED WS G Cape Duck When Duck takes all the credit for catching the Shropshire Slasher, Tech gets annoyed. But when Duck starts to suspect that the Slasher is out for revenge, he's more than willing to let Tech take the glory. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES WS G Sasquashed/ Xtreme Trouble/ A Life Less Guarded When Jerry and Tuffy go camping, Tom frightens them by pretending to be the legendary Bigfoot, but then the real Bigfoot teams up with the mice to scare the wits out of Tom. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY G Waking Nightmare / Because of the Undertoad Mandy needs her beauty sleep, but Billy risks his hide to keep her up all night. -

Low Socioeconomic Status in the University Writing Center Wyn Richards University of Nebraska-Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: English, Department of Department of English Spring 4-17-2018 "Maybe He's the Green Lantern": Low Socioeconomic Status in the University Writing Center Wyn Richards University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Richards, Wyn, ""Maybe He's the Green Lantern": Low Socioeconomic Status in the University Writing Center" (2018). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 140. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/140 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. “Maybe He’s the Green Lantern”: Low Socioeconomic Status in the University Writing Center By Wyn M. Richards A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Shari Stenberg Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2018 “Maybe He’s the Green Lantern”: Low Socioeconomic Status in the University Writing Center Wyn M. Andrews Richards, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2018 Adviser: Shari Stenberg. University students with low socioeconomic status face a variety of unique challenges. With income inequality rising amongst the general population in the US, the gap between students with high socioeconomic status university students identifying as having low socioeconomic status is also increasing. -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything. -

Combined Teachers Guide.Pub

California State Parks Shasta State Historic Park Teacher’s Guide 1 2004 ©California State Parks/Shasta State Historic Park Comments and suggestions about this guide are welcome. Please contact park staff at (530) 243-8194 or P.O. Box 2430 Shasta, CA 96087 2 Shasta State Historic Park Teacher’s Guide Table of Contents General Information 4 Rotation Schedule 8 Rotation Schedule with the Junior Docents 9 Courthouse Museum Activities 10 Shasta Pioneer Union Cemetery Activities 16 Lower Ruins Trail Activities 19 Supplemental Materials 22 “Like our pioneer forefathers of a century ago we are determined that the children of this land shall be trained to rise to their full stature...to give to them a clear picture of present knowledge.” 3 About Your Visit As a general policy of California State Parks, admission fees are waived for school groups. In order to waive the fee at Shasta State Historic Park we require you to complete a School Group Reservation Request (DPR 124). We will need a copy of this form, signed by your school principal, before your field trip date is considered “reserved.” Shasta State Historic Park is available Thursdays and Fridays, year round for educational field trips. A typical field trip will take approximately 3 hours. Many teachers add ½ hour for lunchtime in the park. Field trips are essentially self guided. Park staff is available to answer questions and highlight special resources of the park. Since park staff is usually minimal, participation of well-informed teachers and adult supervisors is essential. Contact Information Please direct questions about school tours and all related correspondence to: Shasta State Historic Park School Group Tours P.O. -

D E E L 5 2 , S U P P L E M E N T 1 , 2 0

http://ngtt.journals.ac.za 1 1 0 2 1, SUPPLEMENT , 2 5 L E E D NED GEREF TEOLOGIESE TYDSKRIF DEEL 52, NOMMERS 1 & 2, MAART & JUNIE 2011 http://ngtt.journals.ac.za NED GEREF TEOLOGIESE TYDSKRIF DEEL 52, SUPPLEMENT 1, 2011 Redaksie: Dr G Brand (redakteur), HL Bosman, JH Cilliers, J-A van den Berg en DP Veldsman. Adres van redaksie: NGTT, Die Kweekskool, Dorpstraat 171, Stellenbosch 7600 (Posadres: NGTT, Fakulteit Teologie, P/sak X1, Matieland 7602; e-posadres: [email protected].) http://academic.sun.ac.za/theology/NGTT.htm Die redaksie vereenselwig hom nie noodwendig met die menings wat deur skrywers in die tydskrif uitgespreek word nie. Redaksiesekretaresse: Me HS Nienaber Medewerkers van NGTT aan SA Universiteite en akademiese instellings: Universiteit van Stellenbosch Proff P Coertzen, KTh August, HJ Hendriks, NN Koopman, DJ Louw, AEJ Mouton, J Punt, DJ Smit, LC Jonker, I Swart, drr Gerrit Brand, AL Cloete, CC le Bruyns, IA Nell, DX Simon, C Thesnaar, RR Vosloo en me EM Bosman. Ekklesia, U.S. Drr CW Burger en JF arais, PM Goosen en C Jones (Navorsingsgenote: Prof A Boesak, Drr Auke Compaan, Christoff Pauw en ds Jan Nieder-Heitmann) Universiteit van Pretoria Proff DE de Villiers, DJ Human, JH le Roux, PGJ Meiring, JC Müller, GJ Steyn, JG van der Watt, CJA Vos, CJ Wethmar, Malan Nel, drr A Groenewald, CJP Niemandt, Graham Duncan en Maake Masango, AS van Niekerk en JM van der Merwe. Instituut vir Terapeutiese Ontwikkeling Prof DJ Kotze Universiteit van die Vrystaat Proff RM Britz, J Janse van Rensburg, SJPK Riekert, SD Snyman, PJ Strauss, DF Tolmie, HC van Zyl, P Verster, J-A van den Berg, J Steyn, en en ds. -

Authority and Integrity in the Modernist Novel by Andrew Bingham a Thesis

Aspects of Intimacy: Authority and Integrity in the Modernist Novel by Andrew Bingham A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in English Language and Literature in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada November, 2018 Copyright © Andrew Bingham, 2018 “Some ideas exist that are unexpressed and unconscious but that simply are strongly felt; many such ideas are fused, as it were, with the human heart.” (Fyodor Dostoevsky, A Writer’s Diary, “Environment,” 1873) “Special methods of thinking. Permeated with emotion. Everything feels itself to be a thought, even the vaguest feelings (Dostoevsky).” (Franz Kafka, Diaries 1910-1923, 21 July 1913) “One must write from deep feeling, said Dostoevsky. And do I? Or do I fabricate with words, loving them as I do? No, I think not. In this book I have almost too many ideas. I want to give life and death, sanity and insanity; I want to criticise the social system, and to show it at work, at its most intense. But here I may be posing.” (Virginia Woolf, Diary, 19 June 1923) “One can, correctly and immediately, comprehend and feel something deeply; but one cannot, immediately, become a person; one must be formed into a person. It is a discipline.” (Fyodor Dostoevsky, A Writer’s Diary, February 1877) “Each spiritual stance creates its own style.” (Witold Gombrowicz, Diary, 495) ii Abstract In the following thesis I strive to offer renewed ways of construing “one’s own,” authority, integrity, and intimacy as literary themes, and appropriate form, provisional tonality, and approximate, inexhaustible address as formal aspects of literary works or methodological tools for literary scholars. -

Making Van Gogh a German Love Story 23 October 2019 to 16 February 2020

PRESS RELEASE MAKING VAN GOGH A GERMAN LOVE STORY 23 OCTOBER 2019 TO 16 FEBRUARY 2020 Städel Museum, Garden Halls Press preview: Monday, 21 October 2019, 11 am #MakingVanGogh Frankfurt am Main, 12 September 2019. From 23 October 2019 to 16 February Städelsches Kunstinstitut 2020, the Städel Museum is devoting an extensive exhibition to the painter Vincent und Städtische Galerie van Gogh (1853–1890). It focuses on the creation of the “legend of Van Gogh” Dürerstraße 2 around 1900 as well as his significance to modern art in Germany. Featuring 50 of his 60596 Frankfurt am Main Telefon +49(0)69-605098-170 key works, it is the most comprehensive presentation in Germany to include works by Fax +49(0)69-605098-111 [email protected] the painter for nearly 20 years. www.staedelmuseum.de PRESS DOWNLOADS AT MAKING VAN GOGH addresses the special role that gallery owners, museums, newsroom.staedelmuseum.en private collectors and art critics played in Germany in the early twentieth century for PRESS AND PUBLIC RELATIONS the posthumous reception of Van Gogh as the “father of modern art”. Just less than Pamela Rohde Telefon +49(0)69-605098-170 15 years after his death, in this country Van Gogh was perceived as one of the most Fax +49(0)69-605098-188 important precursor of modern painting. Van Gogh’s life and work attracted broad and [email protected] lasting public interest. His art was collected in Germany unusually early. By 1914 Franziska von Plocki Telefon +49(0)69-605098-268 there was an enormous number of works by Van Gogh, around 150 in total, in private Fax +49(0)69-605098-188 [email protected] and public German collections.