Low Socioeconomic Status in the University Writing Center Wyn Richards University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tornado Can't Defeat Spirit of West Liberty

THE STATE JOURNAL n FRANKFORT, KENTUCKY n mRCH A 11, 2012 n PAGE D3 Tornado can’t defeat spirit of West Liberty ust when man believes them again before the sun rose homes that once stood on those so vivid that I felt like I was living he has gained some con- the next day. shady hills in Morgan County. there with them in that little log trol, amassed some power, My grandfather moved his They waded in the creek where my house or playing in the yard with JMother Nature quickly puts family in the 1920s to Ashland grandmother had drawn water, the children. Though I am sure him in his place as she did re- where he used his talent as a car- and they found a tree with the ini- they had hardships, they focused cently through the tornadoes that penter to help construct what was tials JLE, ones my grandfather had only on the good times, those pounded our area. Particularly once called Armco Steel Corpora- carved there decades before. hard hit was West Liberty, a town tion. My mother recalled the day My grandfather was actually memories of a loving family in a which, although I have never lived the family boarded the train in one of the most intelligent hu- world that now seems so far away. there, still holds a special place in West Liberty, saying goodbye to man beings I have ever known, Yes, the storm took its toll, my heart, for it is the birthplace Nancy Farley grandparents, aunts, uncles and not to mention a man of great hu- demonstrating to us once again of my maternal grandparents, STATE JOURNAL COLUmNIST cousins, making what seemed mor and wit. -

Sometimes Shocking but Always Hilarious

The Sound of Hammers Must Never Cease: The Collected Short Stories of Tim Fulmer Party Crasher Press ©2009, 2010, 2014, Tim Fulmer. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Tim Fulmer. This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental and perhaps the result of a psychotic breakdown on the reader’s part. This definitive collection of Tim Fulmer’s highly entertaining short work includes an introduction by the author and sixty-one stories that chronicle the restless lives of what have been called Gen X and Gen Y. From the psychotic disillusionment of inner city life in “Chicago, Sir" and “Mogz & Peeting” to the shocking and disturbing discoveries of suburban dysfunction in “It’s Pleonexia” and “Yankee Sierra,” Tim Fulmer tells us everything we need to know about growing up and living in North America after 1967. His characters are very scary people -- people with too much education, too much time on their hands, and too much insight ever to hold down a real job long enough to buy a house and support a family -- in short, people just like how you and I ought to be all the time. These are stories of concealed poets, enemies of the people, awful bony hands, pink pills, sharp inner pains, Jersey barriers, and exquisite corpses. The language throughout is unadorned, accurate, highly crafted, ecstatic, even grammatically desperate. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Finding

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, photographs, books, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2017 Quantity: 12.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: • magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations, etc. • program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules • industry publications • national news clippings • awards program catalogs • network communications, and • camera-ready advertising copy • television production photographs Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/22/2019 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: • Bob Hope • Johnny Carson • Jay Leno • Conan O’Brien • Jimmy Fallon • Disney • Motown • The Emmy Awards • Seinfeld • Saturday Night Live (SNL) • Carson Daly • The Mike Douglas Show • Kennedy & Co. • AM America • Miami University Studio 14 Nineteen original Seinfeld scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Notably, the original pilot scripts are included, which indicate that the original title ideas for the show were Stand Up, and later The Seinfeld Chronicles. -

Program Guide Report

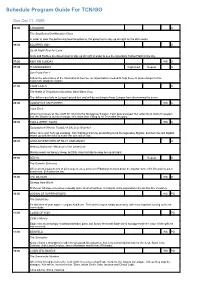

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Oct 11, 2009 06:00 CHOWDER G The Sing Beans/Certifrycation Class In order to cook the performing food Sing Beans, the gang has to stay up all night as the dish cooks. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY G Up All Night/ Pool For Love Andy and Rodney are determined to stay up all night in order to see the legendary Yellow Flash in the sky. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G 07:05 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Sun Probe Part 1 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO G The Battle of Pimpleback Mountain/ Dead Bean Drop The Jellies rip a hole in Lumpus' prized tent and will do anything to keep Lumpus from discovering the secret. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED WS G Cape Duck When Duck takes all the credit for catching the Shropshire Slasher, Tech gets annoyed. But when Duck starts to suspect that the Slasher is out for revenge, he's more than willing to let Tech take the glory. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES WS G Sasquashed/ Xtreme Trouble/ A Life Less Guarded When Jerry and Tuffy go camping, Tom frightens them by pretending to be the legendary Bigfoot, but then the real Bigfoot teams up with the mice to scare the wits out of Tom. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY G Waking Nightmare / Because of the Undertoad Mandy needs her beauty sleep, but Billy risks his hide to keep her up all night. -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything. -

Combined Teachers Guide.Pub

California State Parks Shasta State Historic Park Teacher’s Guide 1 2004 ©California State Parks/Shasta State Historic Park Comments and suggestions about this guide are welcome. Please contact park staff at (530) 243-8194 or P.O. Box 2430 Shasta, CA 96087 2 Shasta State Historic Park Teacher’s Guide Table of Contents General Information 4 Rotation Schedule 8 Rotation Schedule with the Junior Docents 9 Courthouse Museum Activities 10 Shasta Pioneer Union Cemetery Activities 16 Lower Ruins Trail Activities 19 Supplemental Materials 22 “Like our pioneer forefathers of a century ago we are determined that the children of this land shall be trained to rise to their full stature...to give to them a clear picture of present knowledge.” 3 About Your Visit As a general policy of California State Parks, admission fees are waived for school groups. In order to waive the fee at Shasta State Historic Park we require you to complete a School Group Reservation Request (DPR 124). We will need a copy of this form, signed by your school principal, before your field trip date is considered “reserved.” Shasta State Historic Park is available Thursdays and Fridays, year round for educational field trips. A typical field trip will take approximately 3 hours. Many teachers add ½ hour for lunchtime in the park. Field trips are essentially self guided. Park staff is available to answer questions and highlight special resources of the park. Since park staff is usually minimal, participation of well-informed teachers and adult supervisors is essential. Contact Information Please direct questions about school tours and all related correspondence to: Shasta State Historic Park School Group Tours P.O. -

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1

Rick Ludwin Collection Page 1 Rick Ludwin Collection OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Creator: Rick Ludwin, Executive Vice President for Late-night and Primetime Series, NBC Entertainment and Miami University alumnus Media: Magnetic media, magazines, news articles, program scripts, camera-ready advertising artwork, promotional materials, newsletters, correspondence and realia Date Range: 1937-2011 Quantity: 9.0 linear feet Location: Manuscript shelving COLLECTION SUMMARY The majority of the Rick Ludwin Collection focuses primarily on NBC TV primetime and late- night programming beginning in the 1980s through the 1990s, with several items from more recent years, as well as a subseries devoted to The Mike Douglas Show, from the late 1970s. Items in the collection include: magnetic and vinyl media, containing NBC broadcast programs and “FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION” awards compilations program scripts, treatments, and rehearsal schedules industry publications national news clippings awards program catalogs network communications, and camera-ready advertising copy Included in the collection are historical narratives of broadcast radio and television and the history of NBC, including various mergers and acquisitions over the years. 10/9/2013 Rick Ludwin Collection Page 2 Other special interests highlighted by this collection include: Bob Hope Johnny Carson Jay Leno Conan O’Brien Disney Motown The Emmy Awards Seinfeld Saturday Night Live SNL. Carson Daly The Mike Douglas Show Kennedy & Co. AM America Fifteen original Seinfeld table scripts are included; most of which were working copies, reflecting the use of multi-colored pages to call out draft revisions. Other scripts are also contained here--some for primetime, some for broadcast specials such as the landmark three- hour broadcast of SNL’S 25th Anniversary. -

Chapter 7. in the Closet of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Chapter 7 IN THE CLOSET OF SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE: THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES (1970) “I should have been more daring. I have this theory. I wanted to have Holmes homosexual and not admitting it to anyone, including maybe even himself. The burden of keeping it secret was the reason he took dope.” —Billy Wilder1 Watson: “I hope I’m not being presumptuous, but there have been women in your life?” Holmes: “The answer is yes. You’re being presumptuous.” —From The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes About halfway through the episodic The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, the famous detective (Robert Stephens), his trusted companion, Dr. Watson (Colin Blakely), and their client, the Belgian Gabrielle Valladon (Geneviève Page), take an overnight train to Inverness, Scotland, where they hope to fi nd a trace of Gabrielle’s missing engineer husband, Emile. Pretending to be Mr. and Mrs. Ashdown, Holmes and Gabrielle share a sleeping compart ment, while Watson, disguised as their valet, travels in third class. As Holmes in the upper berth and Gabrielle below him get ready for sleep, the conversa- tion turns to the topic of women, and the following exchange ensues: Gabrielle: “Women are never entirely to be trusted—not the best of them.” Holmes: “What did you say?” Gabrielle: “I didn’t say it—you did. According to Dr. Watson.” Holmes: “Oh!” Gabrielle: “He gave me some old copies of Strand Magazine.” Holmes: “The good doctor is constantly putting words into my mouth.” Gabrielle: “Then you deny it?” Holmes: “Not at all. I am not a whole-hearted admirer of womankind.” This open access library edition is supported by Knowledge Unlatched. -

June 11-17, 2015

JUNE 11-17, 2015 Terry Ratliff: Best Visual Artist 13 Whammys and a Room of His Own To step into Terry Ratliff’s Fine Art Gallery on do 35 pieces for one restaurant and they’re packed ev- Broadway in Fort Wayne is to step into a world filled eryday ... Things kept on rolling from there.” with bright, swirling colors and benign, off-kilter Ratliff knew he wanted to be an artist when he was characters who don’t mind being stared at. in first grade. But he had to wait until college before For Ratliff his gallery represents a kind of arrival someone gave him the spark he needed to ignite that as an artist. life-long desire. He went to Franklin “The gallery kind of gives you a College on a football scholarship (as little legitimacy. People love coming a 285-pound offensive lineman) and to your studio, and it’s a mess, but talked his way into a freshman paint- they love seeing that. I hated it. You ing class, a rarity for first-year stu- want to show art where you can walk dents. in and boom it’s hanging on a wall. “My art professor was this crazy It’s a little more legit.” Italian guy named Luigi. He just lit a I have some news for you Terry: fire under me, and I knew this is what You got here a long time ago. But I was going to be doing the rest of my if you need more proof, your 13th life.” Whammy Award for Best Visual That fire still burns. -

Howtoleadwhenyourenotinch

Part 1: understanding our CHa LLenge ambition in good and healthy ways can twist it, and something meant for good can be co-opted by a selfish motive or a narrow focus that is of no benefit to anyone but you. The distortions of our ambition can be simplified into two Partextremes. 1: understanding Like a swinging our Cpendulum,Ha LLenge these two manifesta- tions are equally dangerous. In my own life, I’ve gone to both extremes• In Genesis, at different God times names when the ambition the ambition inside insideyou and me calls has it CHAPTERgrownkabash. distorted.To Each kabash3: of RECLAIMING isus to will bring naturally something lean undertoward KIBOSHyour one controlway or the other,so you and can many make leaders it more will effective, swing backbeautiful, and forthand useful. between these• twoOver extremes. time, the kabash God has given you has been co- opted by sin into kibosh. To kibosh is to bring something under your control for your own good through dominant Part 1:authority.understanding our CHa LLenge • When your kibosh is passive, it leaves you waiting on authorityauthority over them’ to lead,” (Mark abdicating 10:42). your The responsibility kibosh leaders as someone are the ones thatcreated lord intheir God’s authority image. over When those kibosh entrustedis active, to them. though, The it kiboshmanifestsleaders leverage as selfishKILL authority ambition AMBITION not whereto serve you others, are workingbut to serve for themselves.self-advancement Let’s revisit andour diagramthe ability of to Ambition control others Distorted for your and seeThe how firstown it response relatespurposes. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI' Bell & Howell Information and teaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 A GENERIC ANALYSIS OF THE RHETORIC OF HUMOROUS INCIVILITY IN POPULAR CULTURE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial FuljBUment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Laura K. -

ISLE of the ABBEY by Randy Maxwell

ISLE OF THE ABBEY by Randy Maxwell "Isle of the Abbey" is a DUNGEONS & DRAGONS® NOTES FOR THE DUNGEON MASTER adventure for 4-6 characters of up to the third level The lighthouse where characters begin the of experience (about 12 total levels). The adventure is manned by a retired swashbuckler. adventuring party should be basically good in The lighthouse keeper, as he is called locally, is a alignment and of varied classes, with at least one huge, barrel-chested man with a bright-red beard, cleric of 3rd level or two or more clerics of lower and a circlet of thin red-gray hair on his balding levels. head. He was once a mariner and served in glorious conquests and bitter defeats. His usual raiment is a gaudy red and yellow kilt with his BACKGROUND cutlass and dagger hanging from a broad leather In the past three months, the evil clerics of Abbey belt. Isle and a large band of local pirates have quarreled violently, and their struggle may have left Lighthouse Keeper: 5th level fighting man, DX 12, the island uninhabited. The pirates burned the AC 7, hp 22, #AT 1, D 1-6 or 1-4, MV 120', AL N; abbey to the ground, but they suffered so many leather armor, cutlass, dagger. casualties that they could hardly sustain themselves and thus were soon destroyed by the mariners of The retired mariner has long since given up his Portown. Now, the mariners would like to claim the fighting career and now lives the solitary life of a small, strategically located island and build a lighthouse keeper.