University of Groningen Making Place Through Ritual Schulte-Droesch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM Journal Homepage

Antrocom Online Journal of Anthropology vol. 16. n. 1 (2020) 125-132 – ISSN 1973 – 2880 Antrocom Journal of Anthropology ANTROCOM journal homepage: http://www.antrocom.net Literacy Trends and Differences of Scheduled Tribes in West Bengal:A Community Level Analysis Sarnali Dutta1 and Samiran Bisai2 1Research Scholar, 2Associate Professor. Department of Anthropology & Tribal Studies, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal, India. Corresponding author: [email protected] keywords abstract Census data, India, Literacy, The present paper is based entirely on secondary sources of information, mainly drawn Tribal, West Bengal from the 2001 and 2011 Censuses of India and West Bengal. In this paper, an attempt has been made to analyse the present literacy trends of the ethnic communities of West Bengal, and comparing the data over a decade (2001 – 2011). The difference between male and female has also been focused. The fact remains that a large number of tribal women might have missed educational opportunities at different stages and in order to empower them varieties of skill training programmes have to be designed and organised. Implementation of systematic processes like Information Education Communication (IEC) should be done to educate communities. Introduction The term, tribe, comes from the word ‘tribus’ which in Latin is used to identify a group of persons forming a community and claiming descent from a common ancestor (Fried, 1975). Literacy is an important indicator of development among ethnic communities. According to Census, literacy is defined to be the ability to read and write a simple sentence in one’s own language understanding it; it is in this context that education has to be viewed from a modern perspective. -

![International Current Affairs [April 2010]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1057/international-current-affairs-april-2010-281057.webp)

International Current Affairs [April 2010]

International Current Affairs [April 2010] • Belgium became the Europe? s first country to ban burqa. • Pakistan?? s National assembly passed a bill that takes away the President s power to dissolve parliament, dismiss a elected government and appoint the three services Chiefs. Pakistan? s parliament passes 18th amendment which was later signed by Presient cutting President? s powers. • USA and Russia signed Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty(START) that allowed a maximum of 1550 deployed overheads, about 30% lower than a limit set in 2002. The treaty was signed in the Progue Castle. • Emergency was imposed in Thailand. • Nuclear Security Summit held at Washington.It was a 47 nation summit wherein P.M. announced setting up of a global nuclear energy centre for conducting research & development of design systems that are secure, proliferation resistant & sustainable. • PM visit USA & Brazil, a two nation tour. He attended Nuclear Security Summit in USA & India- Brazil-S.Africa(IBSA) and Brazil-Russia-India-China(BRIC) summit in Brasilia (Brazil). • 16th SAARC Summit held in Bhutan in 28-29 April. The summit was held in Bhutan for the first time. It is the silver jubilee summit as SAARC has completed 25 years. The summit central theme was ??Climate Change . The summit recommended to declare 2010-2020 as the ??Decade of Intra-regional Connectivity in SAARC . The 17th SAARC summit will be held in Maldives in 2011. International Current Affairs [March 2010] • China will launch in 2011 unmammed space mode ?? Tiangong I for its future space laboratory. • US internet giant Google close its business in China. • India?? s largest telecom service provider Bharti Airtel buy Zain s Africa operations for an enterprise value of $ 10.7 billion (Rs 49000 crore). -

Tribes in India

SIXTH SEMESTER (HONS) PAPER: DSE3T/ UNIT-I TRIBES IN INDIA Brief History: The tribal population is found in almost all parts of the world. India is one of the two largest concentrations of tribal population. The tribal community constitutes an important part of Indian social structure. Tribes are earliest communities as they are the first settlers. The tribal are said to be the original inhabitants of this land. These groups are still in primitive stage and often referred to as Primitive or Adavasis, Aborigines or Girijans and so on. The tribal population in India, according to 2011 census is 8.6%. At present India has the second largest population in the world next to Africa. Our most of the tribal population is concentrated in the eastern (West Bengal, Orissa, Bihar, Jharkhand) and central (Madhya Pradesh, Chhattishgarh, Andhra Pradesh) tribal belt. Among the major tribes, the population of Bhil is about six million followed by the Gond (about 5 million), the Santal (about 4 million), and the Oraon (about 2 million). Tribals are called variously in different countries. For instance, in the United States of America, they are known as ‘Red Indians’, in Australia as ‘Aborigines’, in the European countries as ‘Gypsys’ , in the African and Asian countries as ‘Tribals’. The term ‘tribes’ in the Indian context today are referred as ‘Scheduled Tribes’. These communities are regarded as the earliest among the present inhabitants of India. And it is considered that they have survived here with their unchanging ways of life for centuries. Many of the tribals are still in a primitive stage and far from the impact of modern civilization. -

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This Page Intentionally Left Blank Shadows in the Field

Shadows in the Field Second Edition This page intentionally left blank Shadows in the Field New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology Second Edition Edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley 1 2008 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2008 by Oxford University Press Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shadows in the field : new perspectives for fieldwork in ethnomusicology / edited by Gregory Barz & Timothy J. Cooley. — 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-532495-2; 978-0-19-532496-9 (pbk.) 1. Ethnomusicology—Fieldwork. I. Barz, Gregory F., 1960– II. Cooley, Timothy J., 1962– ML3799.S5 2008 780.89—dc22 2008023530 135798642 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper bruno nettl Foreword Fieldworker’s Progress Shadows in the Field, in its first edition a varied collection of interesting, insightful essays about fieldwork, has now been significantly expanded and revised, becoming the first comprehensive book about fieldwork in ethnomusicology. -

Inner Frontiers; Santal Responses to Acculturation

Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marne Carn- Bouez R 1991: 6 Report Chr. Michelsen Institute Department of Social Science and Development ISSN 0803-0030 Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marne Carn- Bouez R 1991: 6 Bergen, December 1991 · CHR. MICHELSEN INSTITUTE Department of Social Science and Development ReporF1991: 6 Inner Frontiers: Santal Responses to Acculturation Marine Carrin-Bouez Bergen, December 1991. 82 p. Summary: The Santals who constitute one of the largest communities in India belong to the Austro- Asiatie linguistic group. They have managed to keep their language and their traditional system of values as well. Nevertheless, their attempt to forge a new identity has been expressed by developing new attitudes towards medicine, politics and religion. In the four aricles collected in this essay, deal with the relationship of the Santals to some other trbal communities and the surrounding Hindu society. Sammendrag: Santalene som utgjør en av de tallmessig største stammefolkene i India, tilhører den austro- asiatiske språkgrppen. De har klar å beholde sitt språk og likeså mye av sine tradisjonelle verdisystemer. Ikke desto mindre, har de også forsøkt å utvikle en ny identitet. Dette blir uttrkt gjennom nye ideer og holdninger til medisin, politikk og religion. I de fire artiklene i dette essayet, blir ulike aspekter ved santalene sitt forhold til andre stammesamfunn og det omliggende hindu samfunnet behandlet. Indexing terms: Stikkord: Medicine Medisin Santal Santal Politics Politik Religion -

The State of Art of Tribal Studies an Annotated Bibliography

The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs Contact Us: Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration, Indian Institute of Public Administration, Indraprastha Estate, Ring Road, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi, Delhi 110002 CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) Phone: 011-23468340, (011)8375,8356 (A Centre of Excellence under the aegis of Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) Fax: 011-23702440 INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION Email: [email protected] NUP 9811426024 The State of Art of Tribal Studies An Annotated Bibliography Edited by: Dr. Nupur Tiwary Associate Professor in Political Science and Rural Development Head, Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Tribal Affairs CENTRE OF TRIBAL RESEARCH & EXPLORATION (COTREX) (A Centre of Excellence under Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India) INDIAN INSTITUTE OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION THE STATE OF ART OF TRIBAL STUDIES | 1 Acknowledgment This volume is based on the report of the study entrusted to the Centre of Tribal Research and Exploration (COTREX) established at the Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA), a Centre of Excellence (CoE) under the aegis of the Ministry of Tribal Affairs (MoTA), Government of India by the Ministry. The seed for the study was implanted in the 2018-19 action plan of the CoE when the Ministry of Tribal Affairs advised the CoE team to carried out the documentation of available literatures on tribal affairs and analyze the state of art. As the Head of CoE, I‘d like, first of all, to thank Shri. -

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ______VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ______

The Journal of Parliamentary Information ________________________________________________________ VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 ________________________________________________________ LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI ___________________________________ The Journal of Parliamentary Information VOLUME LXVI NO.1 MARCH 2020 CONTENTS PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITIES PROCEDURAL MATTERS PARLIAMENTARY AND CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENTS DOCUMENTS OF CONSTITUTIONAL AND PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST SESSIONAL REVIEW Lok Sabha Rajya Sabha State Legislatures RECENT LITERATURE OF PARLIAMENTARY INTEREST APPENDICES I. Statement showing the work transacted during the Second Session of the Seventeenth Lok Sabha II. Statement showing the work transacted during the 250th Session of the Rajya Sabha III. Statement showing the activities of the Legislatures of the States and Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 IV. List of Bills passed by the Houses of Parliament and assented to by the President during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 V. List of Bills passed by the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VI. Ordinances promulgated by the Union and State Governments during the period 1 October to 31 December 2019 VII. Party Position in the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha and the Legislatures of the States and the Union Territories PARLIAMENTARY EVENTS AND ACTIVITES ______________________________________________________________________________ CONFERENCES AND SYMPOSIA 141st Assembly of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU): The 141st Assembly of the IPU was held in Belgrade, Serbia from 13 to 17 October, 2019. An Indian Parliamentary Delegation led by Shri Om Birla, Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha and consisting of Dr. Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Ms. Kanimozhi Karunanidhi, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha; Smt. -

Tbe National Christian Council

Proceedings 01 the Seventh Meeting OF Tbe National Christian Council HELD AT NAGPUR December 29, I936-January 1, 1937 Office of the National Chriatian CoUDCil Nelaon Square, NalPur PBINTBD IN INDIA Proceedings of the Seventh Meeting OF The National Christian Council HELD AT NAGPUR DECEJJfBER 29, 1936-JANUARY 1, 1937 Office of the National Christian Council Nelson Square, Nagpur PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS 1937 f:. CONTENTS PAGE OFFICERS, MEMBERS AND LIST OF COMMITTEES PROCEEDINGS 1. PRELIMINARIES 3 II. EVANGELISM AND MASS MOVEMENTS 4 Ill. THE CENTRAL BOARD OF CHRISTIAN HIGHER EDUCATION 27 IV. WORW MISSIONARY CONFERENCE, HlRR 38 V. AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTION 40 YI. FINANCE 42 VII. CHRISTIAN MEDICAL WORK 51 VIII. INDIAN CHRISTIAN MARRIAGE ACT AND DIVORCE 52 IX. REPORTS FROM PROVINCIAL CHRISTIAN COmWILS 53 X. HENRY MARTYN SCHoor, OF ISLAMIC STUDIES 53 XI. MATTERS RELATING TO THE SECRETARIAT 54 XII. COUNCIL FOR ] 937-39 55 XIII. 'J'HE DAY OF PRAYER FOR INDIA 57 XIV. REPORTS SUBMITTED TO THE COUNCIL 57 X V. VOTE OF THANKS 58 APPENDIX I REPORTS OF PROVINCIAl, CHRISTIAN COUNCILS Andhra Christian Council 5f) Bengal and Assam Christian Council U1 Bihar and Orissa Christian Conncil 62 Bombay Christian Council 65 Burma Christian Conncil 66 Madras Representative Christian Conncil 67 Mid·lndia Christian Council 69 Punjab Christian Council 71 United Provinces Christian Council 73 APPENDIX II (a) REPORT OF COMMITTF..E ON RELIGIOUS EDUCATION 75 (b) REPORT ON CHRISTIAN MEDICAL WORK. 1935-36 78 (c) REPORT OF COMMITTEE ON SOCIAL HYGIENE, -

Department Related Parliamentary Standing Committee (RS)

Department Related Parliamentary Standing Committee (RS) Committee on HUMAN RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT Rajya Sabha Member : 6 Vacant : 4 S.NO. Member Name State Party 1 Shri Vishambhar Prasad Nishad Uttar Pradesh Samajwadi Party 2 Shri Derek O Brien West Bengal ALL INDIA TRINAMOOL CONGRESS 3 Shri Sasmit Patra Odisha Biju Janata Dal 4 Dr. Vinay P. Sahasrabuddhe Maharashtra Bharatiya Janata Party 5 Shri Gopal Narayan Singh Bihar Bharatiya Janata Party 6 Shri Akhilesh Prasad Singh Bihar Indian National Congress Lok Sabha Member : 21 Vacant (LS) : 0 S.NO. Member Name State Constituency Party 1 Shri Rajendra Agrawal Uttar Pradesh Meerut BJP 2 Dr. Dhal Singh Bisen Madhya Pradesh Balaghat BJP 3 Shri Santokh Singh Chaudhary Punjab Jalandhar INC 4 Shri Lavu Sri Krishna Devarayalu Andhra Pradesh Narasaraopet YSR Cong.Party 5 Shri Sangamlal Kadedin Gupta Uttar Pradesh Pratapgarh BJP 6 Shri S. Jagathrakshakan Tamil Nadu Arakkonam DMK 7 Shri Sadashiv Kisan Lokhande Maharashtra Shirdi SS Dr. Jaisiddeshwar Shivacharya 8 Maharashtra Solapur BJP Mahaswamiji 9 Shri Asit Kumar Mal West Bengal Bolpur AITC 10 Ms. Chandrani Murmu Odisha Keonjhar BJD 11 Shri Balak Nath Rajasthan Alwar BJP 12 Dr. T. R. Paarivendhar Tamil Nadu Perambalur DMK 13 Shri Chandeshwar Prasad Bihar Jahanabad JD(U) 14 Shri T.N. Prathapan Kerala Thrissur INC 15 Shri Ratansinh Magansinh Rathod Gujarat Panchmahal BJP 16 Shri Jagannath Sarkar West Bengal Ranaghat BJP 17 Dr. Arvind Kumar Sharma Haryana Rohtak BJP 18 Shri Vishnu Dutt Sharma Madhya Pradesh Khajuraho BJP Bhiwani- 19 Shri Dharambir Singh Haryana BJP Mahendragarh 20 Shri S. Venkatesan Tamil Nadu Madurai CPI(M) 21 Shri Ashok Kumar Yadav Bihar Madhubani BJP Department Related Parliamentary Standing Committee (RS) Committee on INDUSTRY Rajya Sabha Member : 9 Vacant : 1 S.NO. -

Adi-Dharam and Jharkhandi Culture: Understanding Adivasi Existence In

Adi-dharam and Jharkhandi Culture: Understanding Adivasi existence in relation to the environmental identity and environmental heritage of Adivasi-Moolvasi communities of Jharkhand. Sudeshna Dutta1 Abstract: Why do the Adivasis of Jharkhand resent the word Development? Since the Koel-Karo movement (Which went on for about thirty-five years) the Adivasis demanded ideal rehabilitation for them. The government officials or policymakers have so far failed to understand the meaning of the ‘ideal rehabilitation.’ In this paper, I argue that without considering the environmental identity of the Adivasi communities, it is impossible to understand the Adivasi interpretation of rehabilitation and the rationals behind such understanding. Adivasi environmental identity, I argue, has a close connection with the land, water, forest. Adivasi culture is closely related to the three elements of nature. Adivasi way of living or Adivasi way of viewing life is practice-oriented and cannot sustain without them. In this paper, I have tried to engage with the three main festivals of Jharkhand to show how the festivals carry the ethos of adi-dharam. The philosophy of Adi-dharam is about maintaining harmonious relationships with the other elements of the ecology. The rationale behind maintaining such relationship is acknowledging the contribution of others in keeping the food-security and food-sovereignty of the community. The structure of the relationships shapes the environmental identity of the Adivasi existence. The rehabilitation programmes, I conclude, need to incorporate the Adivasi interpretation of existence to protect the interest of the Adivasis. Keywords: Environmental Identity, Environmental Heritage, Adi-dharam 1 Sudeshna Dutta is a PhD fellow in the Department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University. -

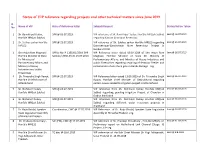

Status of VIP Reference Regarding Projects and Other Technical Matters Since June 2019

Status of VIP reference regarding projects and other technical matters since June 2019 Sl. No Name of VIP Date of Reference letter Subject/Request Status/Action Taken No 1 Sh. Ram Kripal Yadav, SPR @ 03.07.2019 VIP reference of Sh. Ram Kripal Yadav, Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) Sent @ 16.07.2019 Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) regarding Kadvan (Indrapuri Reservior) 2 Sh. Subhas sarkar Hon'ble SPR @ 23.07.2019 VIP reference of Sh. Subhas sarkar Hon'ble MP(LS) regarding Sent @ 25.07.2019 MP(LS) Dwrakeshwar-Gandheswar River Reserviour Project in Bankura (W.B) 3 Shri Arjun Ram Meghwal SPR Lr.No. P-11019/1/2019-SPR VIP Reference letter dated 09.07.2019 of Shri Arjun Ram Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon’ble Minister of State Section/ 2900-03 dt. 25.07.2019 Meghwal Hon’ble Minister of State for Ministry of for Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs; and Ministry of Heavy Industries and Parliamentary Affairs; and public Enterprises regarding repairing of ferozpur Feeder and Ministry of Heavy construction of one more gate in Harike Barrage -reg Industries and public Enterprises 4 Sh. Trivendra Singh Rawat, SPR @ 22.07.2019 VIP Reference letter dated 13.06.2019 of Sh. Trivendra Singh Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon’ble Chief Minister of Rawat, Hon’ble Chief Minister of Uttarakhand regarding Uttarakhand certain issues related to irrigation project in Uttarakhand. 5 Sh. Nishikant Dubey SPR @ 03.07.2019 VIP reference from Sh. Nishikant Dubey Hon'ble MP(Lok Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) Sabha) regarding pending Irrigation Project of Chandan in Godda Jharkhand 6 Sh. -

A ABHAŃGA 1. a Traditional Prosodic and Mould, Prevalent in The

A primary and material-cause of the universe. The world is the ABHAŃGA manifestation ( Ābhāsa ) of the supreme Reality. It is neither 1. A traditional prosodic and mould, prevalent in the the ultimate reality nor an illusion. The world is the relative devotional literature and music of Maharashtra. truth. The theory of ābhāsa-vāda of Tantra, is different from AUTHOR: RANADE A. D. Source: On music and the Pariņāma- vāda of the Sā ṁkhya and Vivartavāda of the Musicians, New Delhi, 1984. Vedānta. Same Ābhāsa- vāda is the theory of creation of the 2. A Marathi devotional song, a popular Folk song of art-forms in Śaiva-tantra. Maharashtra since 13 th Cent. A.D. The composers of these AUTHOR: PADMA SUDHI.; Source: Aesthetic theories songs tried to propound the philosophy of the Bhagavadgītā of India, Vol. III, New Delhi, 1990. and the Bhāgavata Purāņa. It is composed in Obi, a popular metre. There is no limit of the length of the song, and can be ĀBHĀSA-VĀDA sung in any rāga . It is perennial Kīrtana of God, Abhańga 1. In the absolute, the entire variety that we find in the literal meaning is a Kīrtana without break. objective world, is in a state of perfect unity, exactly as the AUTHOR: PADMA SUDHI (thereafter P. S.) whole variety of colours that we find in a full-grown 3. Ābhańga: A term of Hindu Iconography. Ābhańga is that peacock is in a state of perfect identity in the yolk of form of standing attitude in which the centre line from the peacock’s egg.