The Purpose of Art: Intelligent Dialogue Or Mere Decoration?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 1St-18Th, 2012

www.oeta.tv KETA-TV 13 Oklahoma City KOED-TV 11 Tulsa KOET-TV 3 Eufaula KWET-TV 12 Cheyenne Volume 42 Number 9 A Publication of the Oklahoma Educational Television Authority Foundation, Inc. March 1ST-18 TH, 2012 MARCH 2012 THIS MONTH page page page page 2 4 5 6 Phantom of the Opera 60s Pop, Rock & Soul Dr. Wayne Dyer: Wishes Fulfilled Live from the Artists Den: Adele at Royal Albert Hall f March 6 & 14 @ 7 p.m. f March 5 @ 7 p.m. f March 30 @ 9w p.m. f March 7 @ 7 p.m. 2page FESTIVAL “The Phantom of the Opera” at the Royal Albert Hall f Wednesday March 7 at 7 p.m. Don’t miss a fully-staged, lavish 25th anniversary mounting of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s long-running Broadway and West End extravaganza. To mark the musical’s Silver Anniversary, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Cam- eron Mackintosh presented “The Phantom of the Opera” in the sumptuous Victorian splendor of London’s Royal Albert Hall. This dazzling restaging of the original production recreates the jaw-dropping scenery and breath- Under the Streetlamp taking special effects of the original, set to Lloyd Webber’s haunting score. f Tuesday March 13 at 7 p.m. The production stars Ramin Karimloo as The Phantom and Sierra Boggess Under the Streetlamp, America’s hottest new vocal group, as Christine, together with a cast and orchestra of more than 200, including performs an electrifying evening of classic hits from the special guest appearances by the original Phantom and Christine, Michael American radio songbook in this special recorded at the Crawford and Sarah Brightman. -

A Tribute to Betty Price Thank You, Betty

IMPROVING LIVES THROUGH THE ARTSNEWSLETTER OF THE OKLAHOMA ARTS COUNCIL FALL 2007 Thank You, Betty or 33 years, Betty Price has been the voice of the Oklahoma Arts Council. Recently retired Fas Executive Director, Price has been at the helm of this state agency for most of its existence. We couldn’t think of anyone more eloquent than her good friend, Judge Robert Henry to celebrate Betty and her passionate commitment to Oklahoma and to the arts. We join Judge Henry and countless friends in wishing Betty a long, happy and productive retirement. A Tribute to Betty Price From Judge Robert Henry ur great President John Fitzgerald Kennedy once noted: “To further the appreciation of Oculture among all the people, to increase respect for the creative individual, to widen participation by all the processes and fulfillments of art -- this is one of the fascinating challenges of these days.” Betty Price took that challenge more seriously than any other Oklahoman. And, it is almost impossible to imagine what Oklahoma’s cultural landscape would look like without her gentle, dignified, and incredibly Betty in front of the We Belong to the Land mural by Jeff Dodd. persistent vision. Photo by Keith Rinerson forMattison Avenue Publishing Interim Director. Finally, she was selected by the Council to serve as its Executive Director. Betty, it seems, has survived more Oklahoma governors than any institution except our capitol; she has done it with unparalleled integrity and artistic accomplishment. Betty and Judge Robert Henry during the dedication of the Ada Lois Sipuel Fisher portrait by Mitsuno Reedy. -

The Jamison Galleries Collection

THE JAMISON GALLERIES COLLECTION BETTY W. AND ZEB B. CONLEY PAPERS New Mexico Museum of Art Library and Archives Dates: 1950 - 1995 Extent: 7.33 linear feet Contents Part One. Materials on Artists and Sculptors Part Two. Photographs of Works Part Three. Additional Material Revised 01/11/2018 Preliminary Comments The Jamison Galleries [hereafter referred to simply as “the Gallery”] were located on East Palace Avenue, Santa Fe, from August 1964 until January 1993, at which time it was moved to Montezuma Street. There it remained until December 1997, when it closed its doors forever. Originally owned by Margaret Jamison, it was sold by her in 1974 to Betty W. and Zeb B. Conley. The Library of the Museum of Fine Arts is indebted to the couple for the donation of this Collection. A similar collection was acquired earlier by the Library of the records of the Contemporaries Gallery. Some of the artists who exhibited their works at this Gallery also showed at The Contemporaries Gallery. Included in the works described in this collection are those of several artists whose main material is indexed in their own Collections. This collection deals with the works of a vast array of talented artists and sculptors; and together with The Contemporaries Gallery Collection, they comprise a definitive representation of southwestern art of the late 20th Century. Part One contains 207 numbered Folders. Because the contents of some are too voluminous to be limited to one folder, they have been split into lettered sub-Folders [viz. Folder 79-A, 79-B, etc.]. Each numbered Folder contains material relating to a single artist or sculptor, all arranged — and numbered — alphabetically. -

July 10-16, 2015 202 E

CALENDAR LISTING GUIDELINES •Tolist an eventinPasa Week,sendanemail or press release to [email protected] or [email protected]. •Send material no less than twoweeks prior to the desired publication date. •For each event, provide the following information: time,day,date, venue, venueaddress, ticket prices,web address,phone number,brief description of event(15 to 20 words). •All submissions arewelcome.However,eventsare included in Pasa Week as spaceallows. Thereisnocharge forlistings. •Return of photos and other materials cannotbeguaranteed. • Pasatiempo reservesthe righttopublish received information and photographs on The New Mexican website. •Toadd your eventtoThe New Mexican onlinecalendar,visit santafenewmexican.com and ARTS AND ENTERTAINMENT CALENDAR click on the Calendar tab. •For further information contactPamela Beach, [email protected], July 10-16, 2015 202 E. MarcySt., Santa Fe,NM87501, phone: 505-986-3019, fax: 505-820-0803. •Topurchase alisting in The New Mexican CommunityCalendar,contactClaudia Freeman, [email protected], 505-995-3841 CALENDAR COMPILED BY PAMELA BEACH FRIDAY 7/10 TGIF piano recital First Presbyterian Church of SantaFe, 208 GrantAve. Galleryand Museum Openings Pianist CharlotteRowe, music of Liszt, Brahms, Center for ContemporaryArts and Debussy, 5:30 p.m., donations accepted, 1050 Old PecosTrail,505-982-1338 505-982-8544, Ext. 16. The Implication of Form,architectural photographs In Concert by Hayley Rheagan, reception 5-7 p.m., through Oct. 4. Music at the Museum New MexicoMuseum of Art, 107W.PalaceAve., Counter CultureCafé 505-476-5072 930 Baca St., 505-995-1105 James Hornand KittyJoCreek,5:30-7:30 p.m. Group showofworks by members of Santa Fe on the patio,nocharge. Women in Photography, reception 5:30-7:30 p.m., through July 30. -

Rock and Roll Exhibit Opens May 1 at the History Center Wanda Jackson

Vol. 40, No. 4 Published monthly by the Oklahoma Historical Society, serving since 1893 April 2009 Rock and Roll exhibit opens May 1 at the History Center Wanda Jackson. Leon Russell. music scene. Tulsa rivals The Flaming Lips. Cain’s Ballroom. other international cities as Zoo Amphitheatre. home to some of the most ac- KOMA. KMOD. complished Rock and Roll and These people, places, and radio stations Pop music artists in the world. just barely skim the surface of the visitor’s Tulsa musicians were in seri- experience in Another Hot Oklahoma Night: ous demand during the 1960s A Rock and Roll Exhibit. and 1970s. The multitalented Another Hot Oklahoma Night will open Leon Russell, drummer Jim Friday, May 1, 2009, to the membership of Keltner, bassist Carl Radle, the Oklahoma Historical Society with a re- and guitarist J. J. Cale collab- ception at 7 p.m. The gala will include the orated with artists such as launching of a special Rock and Roll issue John Lennon, George Harri- of Oklahoma Today magazine. son, Ringo Starr, the Rolling On Saturday, May 2, 2009, the exhibit Stones, Eric Clapton, and Bob will open to the public. That opening will Dylan. These musicians headed a group Radio Stations.” Local record stores such include a full day of shows by Oklahoma that became known as the “Tulsa Sound” as Rainbow Records and Sound Ware- bands and family fun at the History Center. and will be featured, with many more, in house provided albums to music lovers The exhibit will explore the artists, radio the “Artists” section of Another Hot Okla- who would become members of great local stations, personalities, venues, and fans in homa Night. -

The Native American Fine Art Movement: a Resource Guide by Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba

2301 North Central Avenue, Phoenix, Arizona 85004-1323 www.heard.org The Native American Fine Art Movement: A Resource Guide By Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba HEARD MUSEUM PHOENIX, ARIZONA ©1994 Development of this resource guide was funded by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. This resource guide focuses on painting and sculpture produced by Native Americans in the continental United States since 1900. The emphasis on artists from the Southwest and Oklahoma is an indication of the importance of those regions to the on-going development of Native American art in this century and the reality of academic study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ● Acknowledgements and Credits ● A Note to Educators ● Introduction ● Chapter One: Early Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Two: San Ildefonso Watercolor Movement ● Chapter Three: Painting in the Southwest: "The Studio" ● Chapter Four: Native American Art in Oklahoma: The Kiowa and Bacone Artists ● Chapter Five: Five Civilized Tribes ● Chapter Six: Recent Narrative Genre Painting ● Chapter Seven: New Indian Painting ● Chapter Eight: Recent Native American Art ● Conclusion ● Native American History Timeline ● Key Points ● Review and Study Questions ● Discussion Questions and Activities ● Glossary of Art History Terms ● Annotated Suggested Reading ● Illustrations ● Looking at the Artworks: Points to Highlight or Recall Acknowledgements and Credits Authors: Margaret Archuleta Michelle Meyers Susan Shaffer Nahmias Jo Ann Woodsum Jonathan Yorba Special thanks to: Ann Marshall, Director of Research Lisa MacCollum, Exhibits and Graphics Coordinator Angelina Holmes, Curatorial Administrative Assistant Tatiana Slock, Intern Carrie Heinonen, Research Associate Funding for development provided by the Nathan Cummings Foundation. Copyright Notice All artworks reproduced with permission. -

4Th Q 2017 Newsletter

N E W S L E T T E R www.tsos.org President’s Letter December 4th Quarter issue of 2017 2017 TSOS Newsletter Greetings: Check out the TSOS website at: www.tsos.org where you can find images of sculptures by our new offi- Election of TSOS Officers – two year cers, Tom Gingras and Cari Cabaniss Eggert. Cur- terms: rent Members please check your TSOS website list- I accepted the nomination and election for ing. my second and final term as President. Our new of- ficers are Tom Gringas, Vice President and Cari Ca- Happy Holiday! baniss Eggert, Secretary and Gary Winston has agreed to continue serving as Treasurer. Joe Kenney Email: [email protected] 26th SculptFest April 27-29, 2018: The location of next Sculptfest will be Main Street Round Rock and the Plaza in front of City Hall. Main Street will be closed to traffic in the SculptFest area. Scot Wilkinson, Art and Culture Council of the Arts Round Rock ISD: Director for the City of Round Rock, will provide TSOS accepted an invitation to become a professional management, city resources and adver- Supporting Partner for the RRISD Council of the tising for SculptFest. Clint Howard has agreed to be Arts. The Council is an advisory board that consists the TSOS SculptFest chair for 2018. of community arts partners, arts industry members, Sculpture Purchase: The City of Round Rock has RRISD students, teachers, parents and administra- committed to host SculptFest for a minimum of three tors. The advisory board functions to provide ad- years, and purchase a sculpture for the City Collec- vice, guidance, support and advocacy for the visual tion from an artist exhibiting at SculptFest each year. -

Sean Scully: the Art of the Stripe

81319_Dartmouth 12/5/07 9:31 AM Page 1 HOOD MUSEUM OF ART quarterquarter y y DARTMOUTH COLLEGE Winter 2008 CONTENTS 2 Letter from the Director 3 Special Exhibitions 4–5 Sean Scully: The Art of the Stripe 6–7 The Mark Lansburgh Collection 8–9 Calendar of Events 10–11 Passion for Form: Selections of Southeast Asian Art from the MacLean Collection 12 The Year Ahead 13 The Collections 14 Vital Support: More for Members! 15 Museum News Sean Scully, Wall of Light Summer (detail), 2005, oil on canvas. Purchased through the Miriam and Sidney Stoneman Acquisitions Fund; 2006.16 81319_Dartmouth 12/5/07 9:31 AM Page 2 An acting class takes their work outdoors in the Hood's Bedford Courtyard. Photo by Christine MacDonald. HOOD MUSEUM OF ART STAFF Gary Alafat, Security/Buildings Manager LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Kristin Bergquist, School and Family Programs Coordinator inter presents a series of exciting exhibitions at the Hood Museum of Art to Juliette Bianco, Assistant Director warm our spirit of imagination and creativity. Sean Scully: The Art of the Amy Driscoll, Assistant Curator of Education Stripe offers a study of the ways a great painter can take seemingly limited Patrick Dunfey, Exhibitions Designer/Preparations W Supervisor subject matter and transform it into an endlessly fruitful lifelong examination. We are indebted to Sean Scully for working so generously to help us engage our audiences Rebecca Fawcett, Registrarial Assistant about the joys of abstract painting and the intricacies of its visual language. This single- Kristin Monahan Garcia, Curatorial Assistant for Academic and Student Programming venue show, presented over the entire upper floor of the museum, offers a color-filled Cynthia Gilliland, Assistant Registrar and expansive journey through the four-decade output of one of the most admired painters of our time. -

Sculptures by World-Renowned Artist Allan Houser to Be Displayed at WRWA

WILL ROGERS WORLD AIRPORT Press Release DATE January 15, 2014 Contact: Karen Carney (405) 316-3262/www.flyokc.com Sculptures by World-Renowned Artist Allan Houser To Be Displayed at WRWA OKLAHOMA CITY, January 15, 2014 – Two bronze sculptures by Chiricahua Apache artist Allan Houser, one of the most renowned American artists of the 20th century, will be installed at Will Rogers World Airport this evening. “We are very proud to be able to bring these impressive works of art to the airport,” says Karen Carney, airport spokesperson. “The pieces are remarkable. Their presence will no doubt enhance the overall visitor experience at our airport.” Standing eight feet tall and weighing nearly 1,000 pounds, the bronze entitled Prayer will be displayed in the central concourse near the Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf. The second sculpture, The Future, is a bit smaller and will be located on the lower level by Baggage Claim 4. The locations were chosen so that all visitors to the airport would have an opportunity to enjoy the artwork of Allan Houser. The sculptures are on loan to WRWA from Allan Houser, Inc. of Santa Fe, New Mexico, the family company which represents the artist’s estate. They will be on display, free of charge, through December, 2014. Will Rogers World Airport joins numerous other institutions in Oklahoma City and across the state in celebrating the 100th anniversary of the native Oklahoman’s birth. Celebrating Allan Houser: An Oklahoma Perspective is a partnership of eleven Oklahoma museums and cultural institutions in conjunction with the Oklahoma Museums Association honoring the legacy of Allan Houser. -

NEA Chronology Final

THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1965 2000 A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF FEDERAL SUPPORT FOR THE ARTS President Johnson signs the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act, establishing the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, on September 29, 1965. Foreword he National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act The thirty-five year public investment in the arts has paid tremen Twas passed by Congress and signed into law by President dous dividends. Since 1965, the Endowment has awarded more Johnson in 1965. It states, “While no government can call a great than 111,000 grants to arts organizations and artists in all 50 states artist or scholar into existence, it is necessary and appropriate for and the six U.S. jurisdictions. The number of state and jurisdic the Federal Government to help create and sustain not only a tional arts agencies has grown from 5 to 56. Local arts agencies climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and now number over 4,000 – up from 400. Nonprofit theaters have inquiry, but also the material conditions facilitating the release of grown from 56 to 340, symphony orchestras have nearly doubled this creative talent.” On September 29 of that year, the National in number from 980 to 1,800, opera companies have multiplied Endowment for the Arts – a new public agency dedicated to from 27 to 113, and now there are 18 times as many dance com strengthening the artistic life of this country – was created. panies as there were in 1965. -

Gratitude Can Thanksgivings, Into Blessings

Volume 6 / Issue 17 / November 2016 Gratitude can transform common days into thanksgivings, turn routine jobs into joy, and change ordinary opportunities into blessings. -William Arthur Ward. The City of Sacramento Offices will be closed, Friday November 11th in observance for Veterans Day Parade and November 24th and 25th in observance of Thanksgiving. Neighborhood Services Bi-Weekly Tidbits Calendar Dates 2016 Deadline Dates Release Dates Vol/Issue # Monday, November 7, 2016 Wednesday, November 9, 2016 Vol. 6 Issue 17 Monday, December 5, 2016 Wednesday, December 7, 2016 Vol. 6 Issue 18 Monday, January 9, 2017 Wednesday, January 11, 2017 Vol. 7 Issue 1 Monday, February 6, 2017 Wednesday, February 8, 2017 Vol. 7 Issue 2 Monday, March 6, 2017 Wednesday, March 8, 2017 Vol. 7 Issue 3 Monday, April 10, 2017 Wednesday, April 12, 2017 Vol. 7 Issue 4 Monday, May 8, 2017 Wednesday, May 10, 2017 Vol 7 Issue 5 Monday, June 5, 2017 Wednesday, June 7, 2017 Vol 7 Issue 6 Monday, July 10, 2017 Wednesday, July 12, 2017 Vol 7 Issue 7 Monday, August 7, 2017 Wednesday, August 9, 2017 Vol 7 Issue 8 Monday, September 11, 2017 Wednesday, September 13, 2017 Vol 7 Issue 9 Monday, October 9, 2017 Wednesday. October 11, 2017 Vol 7 Issue 10 Interested in including your event in our Bi-Weekly Tidbits? Email us details and/or a flyer about your event for consideration to [email protected] View the latest issue of Tidbits on our website at http://cityofsacramento.org/ParksandRec/Neighborhood-Services. ~ Page 2 ~ ~ Page 3 ~ ~ Page 4 ~ Now-January 16 - Downtown Sacramento Ice Rink Celebrate the 25th Season of the Downtown Sacramento Ice Rink any day of the week November 4, 2016, through January 16, 2017! At the doorstep of Golden 1 Center in St. -

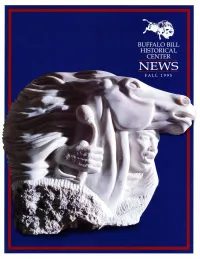

Points-West 1995.09.Pdf

CaruxoAR oF Evrxrs September - Open 8 am to 8 pm October - Open 8 am to 5 pm November - Open 10 am to 3 pm SEPTEMBER Native American Day school program. Buffalo Bill Art Show public program. Artist Donald "Putt" Putman will speak on "What Motivates the Artist?" 3 pm. Historical Center Coe Auditorium. Cody Country Chamber of Commerce's Buffalo Bill Art Show and Sale. 5 pm. Cody Country Art League, across Sheridan Avenue from the Historical Center. OCTOBER 19th Annual Patrons Ball. Museum closes to the public at 4 pm. Museum Tiaining Workshop. Western Design Conference seminar sessions. Patrons' Children s Wild West Halloween Party. 3-5 pm. Buffalo Bill Celebrity Shootout, Cody Shooting A western costume party with special activities and Complex. Three days of shooting competitions, treats for our younger members. including trap, skeet, sporting clays and silhouette shooting events. NOVEMBER One of One Thousand Societv Members Shootout events. Public program: Seasons of the Buffalo.2 pm. Historical Center Coe Auditorium. 19th Annual Plains Indian Seminar: Art of the Plains - Voices of the Present. Public program: Seasons of the Buffalo.2 pm. Historical Center Coe Auditorium. Public program'. Seasons of the Buffalo.2 pm. Historical I€I{5 is putrlished quiutsly # a ben€{it of membershlp in lhe Bufialo Eiil lfistorical Crnter Fu informatron Center Coe Auditorium. about mmberghip contact Jme Sanderu, Director o{ Membership, Bulfalo Bill'l{istorical Centet 7?0 Shdidan Avenuo, Cody, IAI{ 82414 o1 catl (30fl 58Va77l' *t 255 Buffalo Bill Historical Center closes for the season. Requst Bsmjssion to cqpy, xepdni or disftibuie dticles in ary ftedium ox fomat.