Anaemia in Bangladesh: a Review of Prevalence and Aetiology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Potential Benefits of Golden Rice 16 6 Sensitivity Analysis 18 7 Conclusion 19 References 20 Appendix 24

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Zimmermann, Roukayatou; Ahmed, Faruk Working Paper Rice biotechnology and its potential to combat vitamin A deficiency: a case study of golden rice in Bangladesh ZEF Discussion Papers on Development Policy, No. 104 Provided in Cooperation with: Zentrum für Entwicklungsforschung / Center for Development Research (ZEF), University of Bonn Suggested Citation: Zimmermann, Roukayatou; Ahmed, Faruk (2006) : Rice biotechnology and its potential to combat vitamin A deficiency: a case study of golden rice in Bangladesh, ZEF Discussion Papers on Development Policy, No. 104, University of Bonn, Center for Development Research (ZEF), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/32303 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Prevalence and Predictors of Vitamin D Deficiency and Insufficiency

nutrients Article Prevalence and Predictors of Vitamin D Deficiency and Insufficiency among Pregnant Rural Women in Bangladesh Faruk Ahmed 1,*, Hossein Khosravi-Boroujeni 1, Moududur Rahman Khan 2, Anjan Kumar Roy 3 and Rubhana Raqib 3 1 Public Health, School of Medicine, Griffith University, Gold Coast Campus, Gold Coast, QLD 4220, Australia; [email protected] 2 Institute of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Dhaka, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh; [email protected] 3 International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh; [email protected] (A.K.R.); [email protected] (R.R.) * Correspondence: f.ahmed@griffith.edu.au Abstract: Although adequate vitamin D status during pregnancy is essential for maternal health and to prevent adverse pregnancy outcomes, limited data exist on vitamin D status and associated risk factors in pregnant rural Bangladeshi women. This study determined the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency, and identified associated risk factors, among these women. A total of 515 pregnant women from rural Bangladesh, gestational age ≤ 20 weeks, participated in this cross-sectional study. A separate logistic regression analysis was applied to determine the risk factors of vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency. Overall, 17.3% of the pregnant women had vitamin D deficiency [serum 25(OH)D concentration <30.0 nmol/L], and 47.2% had vitamin D insufficiency [serum 25(OH)D concentration between 30–<50 nmol/L]. The risk of vitamin D insufficiency was significantly higher among nulliparous pregnant women (OR: 2.72; 95% CI: 1.75–4.23), those in their first trimester (OR: Citation: Ahmed, F.; 2.68; 95% CI: 1.39–5.19), anaemic women (OR: 1.53; 95% CI: 0.99–2.35; p = 0.056) and women whose Khosravi-Boroujeni, H.; Khan, M.R.; Roy, A.K.; Raqib, R. -

Investment Corporation of Bangladesh Human Resource Management Department List of Valid Candidates for the Post of "Office Sohayok "

Investment Corporation of Bangladesh Human Resource Management Department List of valid candidates for the post of "Office Sohayok" Sl. No Tracking No Roll Name Father's Name 1 1610200000003188 7941 EVA AKTER M ASRAF HOSSEN 2 1610200000003189 1689 MD. ABID HASAN MD. ASRAF ALI 3 1610200000003190 3317 MIZANUR RAHMAN MAZIBUR RAHMAN 4 1610200000003191 4361 MD. KAWSER AHMED LATE MD. TOBARAK ALI 5 1610200000003192 5360 MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM MD. ALA UDDIN 6 1610200000003193 7564 MOKHLESUR NURUL ISLAM 7 1610200000003194 1874 MD. MANIRUZZAMAN MD. ABUL HOSSAIN BAPARI 8 1610200000003195 6010 MD. SAHIDUL HOQUE MD. AZIZUL HOQUE 9 1610200000003196 0571 RAKIBUL ISLAM LATE KHAYEZ UDDIN SARKAR 10 1610200000003197 5492 MD. ABDUR RAHMAN MD. ABDUR ROUF 11 1610200000003198 0803 MD. ASHIF HOSSAIN MD REZAUL HOQUE 12 1610200000003199 2857 MD. AL AMIN ABBAS ALI 13 1610200000003200 2752 MD. RAKIBUL ISLAM MOAZZEM HOSSAIN 14 1610200000003201 5363 ABDUR RAHAMAN MOHAMMAD MOSTAFA KAMAL 15 1610200000003202 5795 RAKIBUL HASAN ABDUL HALIM 16 1610200000003203 0436 MD. FARUK HOSSAIN NURUL ISLAM 17 1610200000003204 6394 ARJUN KUMAR BISWAS BIDHAN KUMAR BISWAS 18 1610200000003205 2111 MD.ARIE OSSAIN MD.GIAS UDDIN 19 1610200000003206 7891 MD. RUHUL AMIN MD. OYAZED ALI 20 1610200000003207 5019 FAHAD AL MAMUN MD FARUK MIAH 21 1610200000003208 1186 MD.MOZAMMEL HAQUE MD.MONSUR ALI 22 1610200000003209 3709 MD. AZIZUL HOQUE MD. NURUL ISLAM 23 1610200000003210 3838 MD. TOHIN MIAH MD. SIRAJ UDDIN 24 1610200000003211 1989 MD.RAJA HASAN MD.SAHJAHAN 25 1610200000003212 1153 RABIN CHANDRA SARKAR GOPAL CHANDRA SARKAR 26 1610200000003213 4954 MD. ZUBAIR MD. MOFIZ UDDIN 27 1610200000003214 4996 MD. MAZED ALI MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM 28 1610200000003215 6104 MD. -

3G-Bengalis-In-Uk-Strand-01.Pdf

Introduction to 1st strand Roots and memory - the history of Bangladesh and the 1971 war of independence Dialogue between first and third generation on the history of Bangladesh and the 1971 war of independence. We begin the oral history with people’s memories of East Pakistan and events leading to the liberation war. We see here the importance of language as both a unifying and divisive factor. Bengali became a rallying point for those in East Pakistan who wanted a fairer political and social deal within Pakistan generally. Urdu became, in contrast, a source of division with the attempt to establish it as the national language very soon after the creation of Pakistan. Although the majority of Bengalis in East Pakistan were Muslims, similar attempts to forge national unity through the politicisation of Islam failed to unite the two wings divided by over a thousand miles of Indian territory. As the interviews make clear, the liberation war was not just fought in the Bengal delta. By 1971 a small but grow- ing Bengali community had been established in the UK and in many places, such as London, Luton, Birmingham and Manchester, they worked with or lived near Pakistanis, who had migrated from the Punjab and Kashmir. It is interesting to note that Bengalis were active in political activity before 1971 as they supported Awami League’s Six Point programme (1966), which demanded greater autonomy for East Pakistan and campaigned for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s release after he was arrested in 1968 (the Agartala conspiracy case). During the war of Bangladesh in 1971, the community played an important role in highlighting the atrocities tak- ing place in Bangladesh, lobbying British government and the international community and raising funds for refugees and Bengali freedom fighters. -

Annual Report 2020 | 3 NOTICE of the 21ST ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

EɲƀƟŸƟĕEáȸdzijȟɼ@ádú In consonance with globalization and free market economy the Global Insurance Limited was launched in the middle of 2000 by a cross section of entrepreneurs encompassing engineers, doctors, real estate developers, businessmen and industrialists. In launching the Company the entrepreneurs were inspired by the vision of a company of substance and quality, capable of playing a major role in the insurance industry of the country. The sponsors formed the Board of Directors and a number of sub-committees designed to render prompt and efficient service to the clients. After 21 years of operation, the Company is well on its way to acquiring a wide range of clients and sound assets and a reserve base. Widely appreciated for being run on time-honored ethics and basics of insurance the Company has come to acquire a good reputation and respectability within such a short time. The Directors are determined to continue with the good works done by the Company with a view to making it a household name in the country and truly synonymous with its promotional Slogan. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL All Shareholders’ Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission Registrar of Joint Stock Companies & Firms Insurance Development & Regulatory Authority Dhaka Stock Exchange Limited Chittagong Stock Exchange Limited Sub: Annual Report for the year ended December 31, 2020 Dear Sir (s), We are delighted to enclose a copy of the Annual Report-2020 together with the Audited Financial Statements for the year ended December 31st, 2020 for your kind information and record. Yours faithfully, Md. Omar Faurk Company Secretary Annual Report 2020 | 3 NOTICE OF THE 21ST ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Notice is hereby given to all Shareholders' of Global Insurance Limited that the 21st Annual General Meeting of the Shareholders' of the Company will be held on Saturday, 14th August 2021 at 11:00 a.m. -

Bsc-List-2021.Pdf

Serial NO USER ID APPLICANT NAME FATHER NAME MOTHER NAME SSC ROLL SSC GPA HSC ROLL HSC GPA STATUS PROGRAM 1 PROGRAM 2 1 BWLBIAR ABDUL KARIM ABDUL JALIL ASRAFUN NAHAR PANNA 151941 5.00 135304 5.00 ELIGIBLE Avionics Aerospace 2 BCKZIWW MD. SADEKUZZAMAN NISHAT MD. NURUL ISLAM MOST. SAFURA BEGUM 197415 5.00 133445 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 3 BOZTVVP SYED JISAN KABIR SYED HUMAUN KABIR MST. SOHELA PARVIN 122848 4.78 117454 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 4 BTOYUFQ JUBAER AL- AMIN EMON MD. NURUL AMIN KHADIZA BEGUM 112310 5.00 134312 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 5 BQEEWWA KHONDOKER AMIMUL AHASAN KHONDOKER SHAHJAHAN HAIDER MOHUA AKTER RUMI 113572 5.00 126831 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 6 BAXLYGI NAZYA MUSTAFIZ MD. HASAN MUSTAFIZ MST. JEBUN NAHAR 132195 5.00 115611 5.00 ELIGIBLE Avionics Aerospace 7 BAHFMZO NOOR-E-TAOHEED ALAMIN NOOR-E-KHAJA ALAMIN SABRINA QUADIR 106558 4.94 144405 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 8 BKALAXP FAHMIDA YASMIN NISHI MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM MOSD. ROWSHAN ARA 116688 5.00 108880 4.50 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 9 BBQMHFL SAYERIN NURESHA ORTHI MD. JAHANGIR ALAM SABINA YASMIN 229105 5.00 120540 5.00 ELIGIBLE Avionics Aerospace 10 BSGBVMD AL IMRAN JAHID HASAN MD. DULAL UDDIN MOST. ZOLEKHA BEGUM 181532 5.00 607569 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 11 BYXRDVN TITHY RANI DAS MANILAL DAS RADHA RANI DAS 108244 5.00 105730 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 12 BOXPDSY MD. AWAL HADI MD. A. HAMID MST. ANJUARA BEGUM 134159 4.89 102828 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 13 BJNCFYD NOSHIN NAWAR MOHAMMAD SHAHJAHAN FARZANA MAINUDDIN 116353 5.00 100538 5.00 ELIGIBLE Avionics Aerospace 14 BAXBRUP MD RAFIUL ISLAM MD AMINUL ISLAM MST. -

Program PDF Version

Table of Contents Conference contacts 2 Conference at a Glance 3 Welcome Note 4 Plenary Session 5 International Program Boards 6 - 7 Proceedings 8 General Information 9 Conference Founder, General Chair Emeritus and Parallel Sessions 10 - 104 Scientific Advisor Sunday 19 July 2020, 17:00-21:30 10 - 25 Gavriel Salvendy Purdue University, USA Monday 20 July 2020, 09:00-13:30 26 - 41 Tsinghua University, P.R. China Tuesday 21 July 2020, 10:00-14:30 42 - 57 and University of Central Florida, USA Wednesday 22 July 2020, 11:00-15:30 58 - 72 Thursday 23 July 2020, 14:00- 18:30 73 - 88 General Chair Friday 24 July 2020, 17:00 – 21:30 89 - 104 Constantine Stephanidis University of Crete and ICS-FORTH, Greece Note: The times indicated are in Email: [email protected] “Central European Summer Time - CEST (Copenhagen)” Conference Administration Email: [email protected] Posters Program Administration Email: [email protected] Sunday, 19 July - Friday, 24 July 2020 106 - 126 Registration Administration Email: [email protected] Student Volunteer Administration Email: [email protected] Communications Chair, Exhibition Chair, HCI International News Editor Abbas Moallem Charles W. Davidson College of Engineering San Jose State University, USA Email: [email protected] 2 l HCI International 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Conference at a Glance Conference Program Overview The times indicated are in “Central European Summer Time - CEST (Copenhagen)” You can check and calculate your local time, using an online time conversion tool, such as -

Annual Report Needs to Be Affixed with a Revenue Stamp of Tk

ANNUAL 2014 REPORT 1 | COMPANY AT A GLANCE | Head Office : Jahangir Tower (3rd Floor), 10, Kawranbazar C/A, Dhaka – 1215 Type of Organization : Financial Institution Nature of Business : Lease Finance, Term Loan Financing, Real Estate & Housing Financing,SME, Financing & Term Deposit Receipt, (TDR), Monthly Savings Scheme (MSS) Number of Directors : 12 Number of Shareholders : 11,895 Authorized Capital : Tk. 5000.00 million Paid Up Capital : Tk. 1106.86 million Statutory Reserve : Tk. 331.06 million Number of Customers : 3506 (Investment) & 1014 (Deposits) Business Thrust Sector : Corporate House, Medium Companies, SME, Housing, Transport Companies etc. Number of Branches : 6 (Six) Business Motto : Efficient customer service & effective financial solutions Auditor : M/s Nurul Faruk Hasan & Co. Legal Adviser : M/s Rani Akter, Advocate, Bangladesh Supreme Court Tax Adviser : Alhaj Md. Serajul Islam E-mail : [email protected] URL (Website) : www.first-finance.com.bd Our Bankers Agrani Bank Ltd. Janata Bank Ltd. Shahjalal Islami Bank Limited Al-Arafah Islami Bank Limited Meghna Bank Limited Social Islami Bank Limited Bangladesh Commerce Bank Mercantile Bank Limited Sonali Bank Ltd. Bangladesh Development Bank Limited Midland Bank Limited South Bangla Agriculture and Commerce Bank Bank Asia Limited Modhumoti Bank Limited Southeast Bank Limited Basic Bank Limited Mutual Trust Bank Ltd. Standard Bank Limited Brac Bank Limited National Bank Limited The City Bank Limited Eastern Bank Limited NRB Commercial Bank Ltd Trust Bank Ltd. Exim -

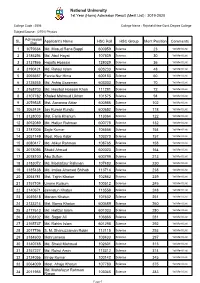

National University 1St Year (Hons) Admission Result (Merit List) : 2019-2020

National University 1st Year (Hons) Admission Result (Merit List) : 2019-2020 College Code : 2506 College Name : Rajshahi New Govt. Degree College Subject/Course : (2701) Physics Admission SL Roll Applicant's Name HSC Roll HSC Group Merit Position Comments 1 3079634 Md. Masud Rana Bappi 600959 Science 23 1st Merit List 2 3185294 Md. Abul Hayat 107509 Science 30 1st Merit List 3 3137866 Hojaifa Hossain 128029 Science 36 1st Merit List 4 3190421 Md. Rafeul Islam 603233 Science 48 1st Merit List 5 3055657 Farzia Nur Hima 600183 Science 60 1st Merit List 6 3125245 Md. Ashiq Uzzaman 603303 Science 70 1st Merit List 7 3168703 Md. Hasibul Hossain Khan 111291 Science 72 1st Merit List 8 3107782 Khaled Mahmud Likhon 101575 Science 94 1st Merit List 9 3079535 Mst. Aonanna Aktar 600986 Science 102 1st Merit List 10 3062424 Joy Kumar Kundu 600652 Science 118 1st Merit List 11 3128003 Mst. Faria Khanum 113364 Science 122 1st Merit List 12 3052089 Md. Hafijur Rahman 600778 Science 132 1st Merit List 13 3187006 Sajib Kumar 106556 Science 154 1st Merit List 14 3051149 Most. Riya Kabir 103270 Science 157 1st Merit List 15 3080417 Md. Atikur Rahman 108765 Science 158 1st Merit List 16 3078095 Shakil Ahmed 600023 Science 164 1st Merit List 17 3078100 Abu Sufiun 600799 Science 213 1st Merit List 18 3183072 Md. Mostafizur Rahman 107483 Science 230 1st Merit List 19 3185438 Md. Imtias Ahamed Shihab 113714 Science 238 1st Merit List 20 3054781 Mst. Tajrin Khatun 102862 Science 239 1st Merit List 21 3157104 Umme Kulsum 100512 Science 245 1st Merit List 22 3140671 Jannatun Khatun 113558 Science 248 1st Merit List 23 3039318 Moriom Khatun 107632 Science 251 1st Merit List 24 3133214 Mst. -

It's Time to Understand Our Role & Responsibility

DIGITAL FINANCE From the Desk of the Editor A MONTHLY SPECIAL OF THE BANGLADESH EXPRESS Dhaka, Wednesday, 12 May, 2021 It's time to understand our Editorial Office 76 Purana Paltan Line, 3rd Floor role & responsibility Dhaka-1000. Contact : +8802-48314265 E-mail: [email protected] When the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic disease has posed a www.thebangladeshexpress.com serious threat to global human health and the India, our neighbouring country is messed with rising death toll, then most News & Commercial Office people in Bangladesh are ignoring health guidelines. Though some Sharif Complex, 2nd Floor people follow these guidelines scrupulously, a majority of Indians 31/1, Purana Paltan, Dhaka-1000 don't think twice before flouting them. Something as simple as a mask is often not worn because people say it's unhealthy or that Editor it's not going to make much of a difference. On the occasion of Eid- ul-Fitre, the rush of homebound people at different ferry ghats and Faruk Ahmed crowd in Eid markets is the bright example of such ignorance which may invite disaster in the days ahead. Managing Editor Shamim Ara When health systems are overwhelmed, both direct mortality from an outbreak and indirect mortality from vaccine- preventable and treatable conditions increase dramatically. Special Correspondents Bangladesh will need to make difficult decisions to balance the K Masum Ahsan demands of responding directly to COVID-19, while Alok Ali Hossain Shahidi simultaneously engaging in strategic planning and coordinated action to maintain essential health service delivery, mitigating UK Correspondents the risk of system collapse. -

Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited Operations Wing Branches Control Division Head Office Dhaka

Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited Operations Wing Branches Control Division Head Office Dhaka Sub: IBBL surrendered unclaimed Deposit to Bangladesh Bank as on 31.12.2017 Sl. No. Name of Branch Present address Parmanent address Account No. Account Type Account Name Father's Name Amount Cumulative Date deposited Deposited to Amount to BB Bangladesh 1 Agrabad Branch Not Available Not Available 4801450 Afzal PO N/A 2315 2315.00 03/04/19 2 Agrabad Branch Not Available Not Available 4805177 M.A.WahabNurul Islam PO N/A 100 2,415.00 03/04/19 3 Agrabad Branch Not Available Not Available 2969965 NurulChowdhury Islam DD N/A 1000 3,415.00 03/04/19 4 Agrabad Branch Girls High School, Chittagong Not Available 3208326 Store DD N/A 100 3,515.00 03/04/19 5 Local Office Not Available Not Available 2210809 DD Payable KISHOR KANTHA N/A 1400 4,915.00 03/04/19 6 Local Office Not Available Not Available 45612 DD Payable LION DIERCTOR N/A 280 5,195.00 03/04/19 7 Local Office Not Available Not Available 84286 DD Payable JAMIATUL MODARESIN N/A 1250 6,445.00 03/04/19 8 Not Available Not Available ABDUR RAZZAK,BAR AT 03/04/19 61379 800 Local Office DD Payable LAW N/A 7,245.00 9 Local Office Not Available Not Available 115154 DD Payable AJKER KAGAJ N/A 900 8,145.00 03/04/19 10 Local Office Not Available Not Available 140506 DD Payable AJKER KAGAJ N/A 1260 9,405.00 03/04/19 11 Local Office Not Available Not Available 205528 DD Payable SIR. -

Final Report on Completed Database and Survey Impact Assessment of E-GP and Other Selected Interventions (Contract Package # CPTU/S-10)

Final Report on Completed Database and Survey Impact Assessment of e-GP and Other Selected Interventions (Contract Package # CPTU/S-10) Submitted to: Director General Central Procurement Technical Unit (CPTU) and Project Director, DIMAPPP CPTU Bhaban, Planning Commission Premises, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Prepared by MIDAS MIDAS Centre (11th floor), Plot # 5, Road # 16, Dhanmondi, Dhaka 1209, Bangladesh Telephone: 9103421, 9113765, 9146579, Fax: 58153580 email: [email protected], website: www.midas.org.bd June 2018 Acknowledgements MIDAS would like to acknowledge CPTU, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh and the World Bank for commissioning this ‘Impact Assessment of e-GP and Other Selected Interventions’, which attempts to measure the beneficial impact of e-GP System over the paper based tendering process. Our sincere gratitude goes to CPTU’s Mr. Md. Faruque Hossain, Director General, Mr. Shish Haider Chowdhury, Director, Mr. Md. Aziz Taher Khan, Director, Mr. Md. Aknur Rahman, Deputy Director, and The World Bank’s Mr. Jurgen Rene Blum, Senior Public-Sector Management Specialist, Dr. Zafrul Islam, Lead Procurement Specialist, Mr. Ishtiak Siddique, Senior Procurement Specialist and Ms. Sushmita Samaddar, e- GP Impact Evaluation Coordinator for their attention and continuous support throughout the whole process. The technical inputs and guidance provided by The World Bank was highly appreciated and instrumental for the successful completion of this entrusted assignment. We also like to extend our gratitude to all the authorities of three Domains (LGED, RHD and BWDB) who had contributed to this digital survey in many ways during the data collection process.