Play and Folklore No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Daycare Schedule Week 11 (7/27 - 7/31) Groups 1 and 2

2020 Daycare Schedule Week 11 (7/27 - 7/31) Groups 1 and 2 SWIM AT VINTON Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Before Care Before Care Before Care Before Care Before Care 7:30-9:00 7:30-9:00 7:30-9:00 7:30-9:00 7:30-9:00 Homeroom (107) Homeroom (107) Homeroom (107) Homeroom (107) Homeroom (107) 9:00-9:15 Snack in Homeroom 9:00-9:15 Snack in Homeroom 9:00-9:15 Snack in Homeroom 9:00-9:15 Snack in Homeroom 9:00-9:15 Snack in Homeroom Just Dance or Movie Just Dance 9:15-10:15 Playground 9:15-10:15 9:15-10:15 Game Room 9:15-10:15 9:15-10:15 Playground (Annex) (Annex) Pac-Man Tag / NSC / Just Dance Chalk / Tic-Tac-Toe Just Dance 10:15-11:00 10:15-11:00 Chalk 10:15-11:00 Playground 10:15-11:00 10:15-11:00 (Annex) (Basketball Court) (Annex) (Basketball Court) Poison Frog / Mafia Paper Plate Fox 11:00-11:30 Lunch in Homeroom 11:00-11:30 Lunch in Homeroom 11:00-11:30 Lunch in Homeroom 11:00-11:30 11:00-11:30 (Homeroom) (Homeroom) Ball of Wonder Paper Plate Turtles 11:30-12:00 Walk to Vinton 11:30-12:00 11:30-12:00 11:30-12:00 Lunch in Homeroom 11:30-12:00 Lunch in Homeroom (Homeroom) (Homeroom) Silent Ball / Hangman / Scene It / Paper Plate Scooter Soccer / Just Dance 12:00-2:00 Swim at Vinton 12:00-12:30 Hot Potato 12:00-12:30 12:00-12:30 Dinos 12:00-12:30 Scooter Tag (Annex) (Homeroom) (Homeroom) (Gym) Giant Soccer / Rainbow Hunt / 2:00-2:30 Walk back to McAllister 12:30-2:00 Playground 12:30-2:00 Uncle John 12:30-2:00 Game Room 12:30-2:00 Cornhole / Jackpot (Field) (Front Field) Sharks and Minnows / Steal the Bacon / Shaniqua Movie Secret Agent / 2:30-3:30 Game Room 2:00-3:30 2:00-3:30 2:00-3:30 / Capture the Flag 2:00-3:30 Game Room (Annex) What Time Is It, Mr. -

Bushfires in Our History, 18512009

Bushfires in Our History, 18512009 Area covered Date Nickname Location Deaths Losses General (hectares) Victoria Portland, Plenty 6 February Black Ranges, Westernport, 12 1 million sheep 5,000,000 1851 Thursday Wimmera, Dandenong 1 February Red Victoria 12 >2000 buildings 260,000 1898 Tuesday South Gippsland These fires raged across Gippsland throughout 14 Feb and into Black Victoria 31 February March, killing Sunday Warburton 1926 61 people & causing much damage to farms, homes and forests Many pine plantations lost; fire New South Wales Dec 1938‐ began in NSW Snowy Mts, Dubbo, 13 Many houses 73,000 Jan 1939 and became a Lugarno, Canberra 72 km fire front in Canberra Fires Victoria widespread Throughout the state from – Noojee, Woods December Point, Omeo, 1300 buildings 13 January 71 1938 Black Friday Warrandyte, Yarra Town of Narbethong 1,520,000 1939 January 1939; Glen, Warburton, destroyed many forests Dromona, Mansfield, and 69 timber Otway & Grampian mills Ranges destroyed Fire burnt on Victoria 22 buildings 34 March 1 a 96 km front Hamilton, South 2 farms 1942 at Yarram, Sth Gippsland 100 sheep Gippsland Thousands 22 Victoria of acres of December 10 Wangaratta grass 1943 country Plant works, 14 Victoria coal mine & January‐ Central & Western 32 700 homes buildings 14 Districts, esp >1,000,000 Huge stock losses destroyed at February Hamilton, Dunkeld, Morwell, 1944 Skipton, Lake Bolac Yallourn ACT 1 Molongolo Valley, Mt 2 houses December Stromlo, Red Hill, 2 40 farm buildings 10,000 1951 Woden Valley, Observatory buildings Tuggeranong, Mugga ©Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority, State Government of Victoria, 2011, except where indicated otherwise. -

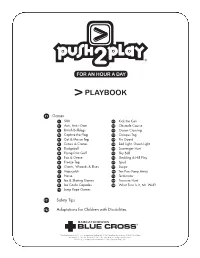

Playbook Games (PDF)

® PLAYBOOK V P1 Games P1 500 P11 Kick the Can P1 Anti, Anti i-Over P12 Obstacle Course P2 British Bulldogs P13 Ocean Crossing P2 Capture the Flag P13 Octopus Tag P3 Cat & Mouse Tag P14 Pin Guard P3 Crows & Cranes P14 Red Light, Green Light P4 Dodgeball P15 Scavenger Hunt P4 Flying Disc Golf P15 Sky Ball P5 Fox & Geese P16 Sledding & Hill Play P6 Freeze Tag P17 Spud P6 Giants, Wizards & Elves P17 Swipe P7 Hopscotch P18 Ten Pass Keep Away P7 Horse P19 Terminator P8 Ice & Skating Games P19 Treasure Hunt P9 Ice Castle Capades P20 What Time Is It, Mr. Wolf? P10 Jump Rope Games P21 Safety Tips P23 Adaptations for Children with Disabilities ®Saskatchewan Blue Cross is a registered trade-mark of the Canadian Association of Blue Cross Plans, used under licence by Medical Services Incorporated, an independent licensee. Push2Play is a registered trade-mark of Saskatchewan Blue Cross. HOW TO PLAY: Choose 1 player to be the first thrower. The rest of the players should be 15 to 20 steps away from Players the thrower. 3 or more The thrower shouts out a number and throws the ball toward the group Equipment so everyone has an equal chance of catching it. Ball The player who catches the ball gets the number of points the thrower shouted. The thrower continues to throw the ball until another player makes enough catches to add up to 500 points. This player now becomes the thrower. CHANGE THE FUN: If a player drops the ball, the points shouted out by the thrower are taken away from the player’s score. -

UNP-0121 Traditional Street Games

UNP-0121 TraditionalARCHIVE Street Games UNP-0121 Traditional Street Games Table of Contents Why Street Games? .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 1 The Problems................................................................................................................................................. 1 Why Street Games......................................................................................................................................... 2 Helpful Hints for Game Leaders .............................................................................................................................. 3 Street Games ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Egg or Balloon Toss ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Hit the Stick.................................................................................................................................................... 5 Hopscotch ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Human -

Fyke-Netting Guidelines, Updated 07.19

Platypus Fyke-netting Guidelines Introduction This document (most recently revised in July 2019) aims to (1) identify the welfare issues that can arise when a platypus is captured in a fyke net and outline ways to reduce these risks, (2) identify the welfare issues for vertebrate by-catch that can arise when fyke nets are set for platypus and outline ways to reduce these risks, and (3) describe recommended protocols for platypus transport and handling, how best to deal with captured animals that are hypothermic or entangled in litter, and how best to release a platypus back to the wild (see Appendix 1). Although mainly drawn from the experience of APC biologists working in Victoria, the principles outlined below should be widely relevant across the platypus’s range. Platypus welfare issues associated with fyke-netting Drowning. By dropping its heart rate to as little as 1.2 beats per minute, an inactive platypus can survive underwater for up to 11 minutes (Evans et al. 1994). However, this interval is reduced to less than 3 minutes when animals are active (Grant et al. 2004). The platypus will therefore drown quickly if held inside a submerged fyke net. This is most likely to occur if water levels rise after nets have been set, e.g. due to rainfall. Increased water depth and/or flow velocity may inundate fyke nets or cause them to collapse after tearing them loose from their anchoring points. Hypothermia. The platypus normally maintains a body temperature close to 32oC in both air and water (Grant and Dawson 1978a; Grant 1983). -

100 Games from Around the World

PLAY WITH US 100 Games from Around the World Oriol Ripoll PLAY WITH US PLAY WITH US 100 Games from Around the World Oriol Ripoll Play with Us is a selection of 100 games from all over the world. You will find games to play indoors or outdoors, to play on your own or to enjoy with a group. This book is the result of rigorous and detailed research done by the author over many years in the games’ countries of origin. You might be surprised to discover where that game you like so much comes from or that at the other end of the world children play a game very similar to one you play with your friends. You will also have a chance to discover games that are unknown in your country but that you can have fun learning to play. Contents laying traditional games gives people a way to gather, to communicate, and to express their Introduction . .5 Kubb . .68 Pideas about themselves and their culture. A Game Box . .6 Games Played with Teams . .70 Who Starts? . .10 Hand Games . .76 All the games listed here are identified by their Guess with Your Senses! . .14 Tops . .80 countries of origin and are grouped according to The Alquerque and its Ball Games . .82 similarities (game type, game pieces, game objective, Variations . .16 In a Row . .84 etc.). Regardless of where they are played, games Backgammon . .18 Over the Line . .86 express the needs of people everywhere to move, Games of Solitaire . .22 Cards, Matchboxes, and think, and live together. -

Winter Sliding Rules

WINTER SLIDING RULES 1. All students must have snow pants on. 2. School sliders only allowed. Students are not permitted to bring sleds, GT's or sliders of their own to school. 3. No standing on crazy carpets. 4. One person at a time only on the slider. 5. All students must vacate the hill when supervisor's whistle blows. (Whistle will blow 3-4 minutes before bell time.) 6. Students are responsible for returning their slider to the helpers at the bins. 7. Students are not allowed on the far side of the sliding hill - only on the main area where there is constant supervision. 8. Students will be expected to walk up the hill in the designated areas. Play safe, follow RRC expectations, and have fun! Check out our school website at: www.sd57.bc.ca/school/ronb Contact: Mr. Lawrence Originally created by Mr. Lawrence in 2005 for the Playground Program. Teaching students how to play! Reprinted and added to Ron Brent website 2014. STEAL THE BACON /TRY Welcome: Whether you are a staff member, parent, or student (also known as “Get Three”, “Try” or “The Steal Game”) we hope that you will feel welcome at Ron Brent School. Where to play: field Outdoor Supervisors: # of players: two teams (unlimited) grade levels: all • vest equipment: 5 hula hoops A beanbags • clipboard/or in vest pocket (gotcha & referral forms) This is a great game. It combines a tremendous how to play: Page # 2 PLAYGROUND MAP cardiovascular workout, agility, strategy and teamwork! It is suitable for all ages. Page # 3 SCHOOL RULES - "O" TOLERANCE Divide the class into 4 groups- if possible, use hoops. -

Department of Parks and Recreation Summer

City of Sterling Heights - Department of Parks and Recreation Summer Playground Schedule: Davis 7/29/19-8/2/19 Office Number: 586.446.2700 Playground Coordinator: Mike Capozzoli (586) 265-9165 Senior Leader: Rebecca Cilluffo Junior Leaders: Hana Hardy, Michael Byszko Aide: Alexa Sorenson, Hailey Morin 3rd and Under 4th and Up Monday Monday 9:00 RC Organizational Meeting 9:00 RC Organizational Meeting 9:15 HH Klump 9:15 AS Human Knot 10:00 AS A/C: Paper Plate Jellyfish 10:00 MB Army Ball 10:30 MB Jump Rope 10:30 HH A/C: Dreamcatchers 11:00 AS Scooter Tag 11:00 HH Zip Zap Zoom 11:30 MB Parks and Rec 2 Step 11:30 MB Parks and Rec 2 Step 12:00 Lunch 12:00 Lunch 12:30 HH Board Games and Cards 12:30 HH Board Games and Cards 1:00 AS A/C: Tournament Day Flag 1:00 AS A/C: Tournament Day Flag 1:30 AS Steal the Bacon 1:30 HH Lightning 2:00 AS Head or Catch 2:00 HH Army Navy 2:30 MB Dodgeball 2:30 MB Dodgeball Tuesday Talent Show Tuesday Talent Show 9:00 RC Organizational Meeting 9:00 RC Organizational Meeting 9:15 HH Straddle Ball 9:15 HH Spoons 10:00 AS A/C: Fingerprint Sheep 10:00 AS Floor Hockey 10:30 MB Tournament Kickball 10:30 MB Tournament Kickball 11:00 AS Spiders and Flies 11:00 HH A/C: 3D Balloon or Heart 11:30 MB Doctor Spy 11:30 MB Doctor Spy 12:00 Lunch 12:00 Lunch 12:30 HH Board Games and Cards, Practice 12:30 HH Board Games and Cards, Practice 1:00 AS Talent Show 1:00 AS Talent Show 1:30 AS Pillo Polo 1:30 MB Throw and Go 2:00 AS A/C: Draw a Leader 2:00 AS A/C: Draw a Leader 2:30 MB Calling all Cars 2:30 HH Guard the Pin Wednesday -

Table of Contents

- TABLE OF CONTENTS BOOKS AND CHAPTERS PUBLISHED............................................................................2 JOURNAL PUBLICATIONS ...............................................................................................4 TECHNICAL AND RESEARCH PAPERS..........................................................................9 CREATIVE WORKS ............................................................................................................10 PUBLISHED REVIEWS.......................................................................................................15 PUBLISHED PROCEEDINGS.............................................................................................17 SCHOLARLY PRESENTATIONS.......................................................................................19 EDITORIAL RESPONSIBILITIES ......................................................................................35 GRANTS................................................................................................................................38 PUBLIC SCHOLARSHIP AND CREATIVE ACTIVITIES................................................43 UNDERGRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH...................................................................50 GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH ................................................................................59 HONORS AND AWARDS ...................................................................................................62 1 BOOKS AND CHAPTERS PUBLISHED MELVIN AND VALORIE BOOTH COLLEGE -

Central Region

Section 3 Central Region 49 3.1 Central Region overview .................................................................................................... 51 3.2 Yarra system ....................................................................................................................... 53 3.3 Tarago system .................................................................................................................... 58 3.4 Maribyrnong system .......................................................................................................... 62 3.5 Werribee system ................................................................................................................. 66 3.6 Moorabool system .............................................................................................................. 72 3.7 Barwon system ................................................................................................................... 77 3.7.1 Upper Barwon River ............................................................................................... 77 3.7.2 Lower Barwon wetlands ........................................................................................ 77 50 3.1 Central Region overview 3.1 Central Region overview There are six systems that can receive environmental water in the Central Region: the Yarra and Tarago systems in the east and the Werribee, Maribyrnong, Moorabool and Barwon systems in the west. The landscape Community considerations The Yarra River flows west from the Yarra Ranges -

NONCOMPETE GAMES 2018.Cdr

WHY NONCOMPETITIVE RECREATION? THE ANSWER: COOPERATIVE GAMES The concept behind noncompetitive recreation can be either hard to understand or hard to accept or both! So who needs games nobody loses? Too often games have become rigid, judgmental, too highly organized and excessively goal-oriented. Have you seen children left out, eliminated to sit out, always chosen last, rejected and wondered why? Many children quit organized sports early because of pressure or they don’t feel they are good enough. We need to find ways for plain old fashioned fun Cooperative games offer a positive alternative. These interactive games provide opportunities for challenge, stimulation and success while eliminating the fear of failure. They foster greater communication, trust, social interaction, acceptance and sharing. Children play with one another instead of against one another. As partners instead of opponents we compete against the limits of our own abilities instead of against each other. Everybody must cooperate in order to accomplish the goals or meet the challenge. The beauty of the games lies in their versatility and adaptability. In most cases there is inexpensive or no equipment necessary. Rules need not to be strictly adhered to. Instead of being eliminated, players change roles or sides or teams and keep playing. Players can work out their own details. These games can reaffirm a child’s confidence in their selves and help them in their willingness to try new experiences. You can bring out creativity and even a boldness they never knew they had. The games can help build a “WHY NOT?” Attitude. NEVER lose sight of the fact that the primary reason children play games is to have fun. -

Increasing-Activity-Games

COLUMN: " The New P.E. & Sports Dimension " The column that opens your day by opening your mind Increasing physical activity in schools through the use of playground games by Dr. Joanne Margaret Hynes-Hunter Numerous physical educators are taking their classes outside onto the playground due to limited space and/or equipment, large class sizes, inadequate budgets, and as an intervention strategy in the increasing epidemic of childhood obesity. Teachers still want to provide students with the best possible learning experiences given limited resources and increase children's physical activity levels. Research findings performed by Peaceful Playgrounds (2006) found playground games: (1) increase children's energy expenditures. Students utilizing playground markings increased their energy expenditure significantly over the control groups, (2) increase activity levels in primary and junior schools. Use of playgrounds painted with multicolored markings increase physical activity, and (3) increase student's knowledge in game rules, and sports skills. If these increases can be sustained on playgrounds, it could be a valuable contribution to health-related physical activity recommendations for young people. How does a teacher decide what games to play on the playground that will increase (1) energy expenditures, (2) physical activity levels, and (3) student knowledge in game rules and sport skills? There are many games and activities that have been played on playgrounds for generations. Unfortunately, many "traditional" playground games (i.e. King of the hill, Red Rover) are not developmentally appropriate because as part of the rules, children are hitting, pushing, knocking down one another in an effort to win. However, there are some playground games that offer an excellent opportunity for growth and learning: i.e.