INFORMATION Ta USERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INFORMATION Ta USERS

INFORMATION Ta USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, sorne thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quailly of this reproduction is dependent upon the quallty of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print. colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. ln the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher qually 6- x 9- black and white photographie prints are available for any photographs or Ulustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly ta arder. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Raad. Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 USA 800-521.Q600 Personal Identity in the Noveis orMa..~ Frisch and Luigi PirandeUo Rachel Remington German Department, McGill University, Montreal A thesis submitted ta the Faculty ofGraduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment ofthe requirements ofthe degree of Master ofArts ©Rachel Remington 1999 NationaILJbrary BibliothèQue nationale 1+1 ofC8nada du canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bib60graphic seNices services bibliographiques 395 Wellington street 395. -

Title:'I Have No Language for My Reality': the Ineffable As Tension in the 'Tale' of Bluebeard Author(S): Marga I. Weigel Public

Page 1 of 7 Title:'I Have No Language for My Reality': The Ineffable as Tension in the 'Tale' of Bluebeard Author(s): Marga I. Weigel Publication Details: World Literature Today 60.4 (Autumn 1986): p589-592. Source:Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism. Ed. Janet Witalec. Vol. 121. Detroit: Gale, 2002. From Literature Resource Center. Document Type:Critical essay Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning Full Text: [(essay date autumn 1986) In the following essay, Weigel explores the role of communication and speech in Bluebeard.] Following acquittal on charges of murdering a prostitute, Felix Theodor Schaad, M.D., begins to search for the reasons why his life has been a failure. The public cross-examination in the courtroom is followed by Schaad's private cross-examination, an attempt to determine his guilt which ultimately drives him to confess the murder and shortly thereafter to attempt suicide. In the last analysis he is indeed convinced that he is guilty, although he has consistently maintained, both to the court and afterward to himself, that he did not commit the murder.1 It may be of interest and perhaps not unimportant for Frisch's literary development that a variant of this "tale" appeared in the novel Gantenbein (1964), almost twenty years earlier. A "personality, a cultured man"2 is brought before the court and accused of the murder of his former lover Camilla, a prostitute. Far more than the sum of the evidence against him, it is his behavior which makes him suspect: "He can't find the words in which to express complete innocence" (262). -

Personal Identity in the Noveîs of Ma.X Frisch and Luigi Pirandello

Personal Identity in the Noveîs of Ma.x Frisch and Luigi Pirandello Rachel Remington German Department, McGiii University, Montreal A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfiiment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts QRacheI Remington 1999 AcquisÏns and Acquisitions et Bibliogmptiic Services senrices biitiraphiques The author lm granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exchive licence aliowhg the exclusive permettant a la National Lihry of Canada to Bbhothèque nationaie du Canada de reproduce, Ioan, dïsûiiute or seU reproduire, prêter, dkîriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thése sous paper or ektronic formats. la forme de microfichel& de reprodnction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retaias omership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts hm it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantieis may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent êûe imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son p&ssion. autorisation. Table of Content Table of Content Acknowledgements Abstract in English Abstract in French introduction Chapter 1: Pirandello and Frisch htroduc tion infiuence? Pirandello and the nouveau roman Frisch and the nouveau roman Modernism and Postmodemism Notes Chapter 2: 11 fii Mattia Pascal and StilIer introduction Paralle1 Stories Starting Point and Crisis New Life Under New Ideotity Retun Home Different Narrative Structures The ''Moral'' of the Story Roif and the Critics n fit Don EIigio and the Critics The Unconscious Conclusion Notes . -

The Scofield

THE SCO FIELD O MAX FRISCH IDENTITY ISSUE 1.4 SPRING 2016 THE SCOFIELD IAN FRANCIS THE SCO FIELD 1.4 “So it is not because I feel a duty to teach or convert the public that I publish my things but because, if one is to recognize one’s own identity, one needs imaginary readers.” MAX FRISCH, MONTAUK Interview Disaster “Here Frisch for the first time elaborated on one of his dominant themes, by some critics the central theme of his oeuvre: the search for identity as the questioning of the existence of a self-contained character or personality, its dependence on the reciprocity of interpersonal image-making, and the impossibility of escaping from the roles we assign to each other.” GERHARD F. PROBST, INTRODUCTION TO PERSPECTIVES ON MAX FRISCH “I know my literary trademark is the problem of identity, MAX FRISCH IDENTITY even though I do not identify with this trademark myself. But both my trademark and I are fine with this.” MAX FRISCH IN AN INTERVIEW WITH DIETER E. ZIMMER FROM DIE ZEIT ISSUE 1.4 SPRING 2016 PAGE 2 THE SCOFIELD TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Scofield Thayer 2 Markers of Silence and Contemplation: A 28 Sculpture by Gaston Lachaise Conversation in Three Parts with Tony Perez, Jakob Vala, and Jonathan Dee Interview Disaster 2 Interview by Conor Higgins Painting by Ian Francis And Dreaming 32 Table of Contents 3 Painting by Jennifer Packer “That Brought Him to That Creaking Room 33 Always a Question 8 Was Age”: Max Frisch’s Man in the Holocene Letter from the Editor by Tyler Malone Essay by Sven Birkerts Who Is That? 12 Ghost Chamber with the Tall Door (New 39 Photograph by Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr. -

Homo Faber Frisch.Pdf

Max Frisch - Homo faber - 1 - Max Frisch - Homo faber Max Frisch Homo faber Ein Bericht Für meinen Schatz Nicole Es gibt im Leben viele Dinge die zerbrechlich sind, doch erst wenn mein Herz zerbricht, wird meine Liebe grenzenlos sein suhrkamp taschenbuch 354 - 2 - Max Frisch - Homo faber Max Frisch, am 15. Mai 1911 in Zürich geboren, starb dort am 4. April 1991. Seine wichtigsten Prosaveröffentlichungen: Tagebuch 1946 - 1949 (1950), Stiller (1954), Homo faber (1957), Mein Name sei Gantenbein (1964), Tagebuch 1966 - 1971 (1972), Dienstbüchlein (1974), Montauk (1975), Der Traum des Apothekers von Locarno. Erzählungen (1978), Der Mensch erscheint im Holozän. Eine Erzählung (1979), Blaubart. Erzählung (1982). Stücke u. a.: Graf Öderland (1951), Don Juan oder Die Liebe zur Geometrie (1953), Biedermann und die Brandstifter (1958), Andorra (1961), Biografie: Ein Spiel (1967) und Triptychon, Drei szenische Bilder (1978). Sein Werk, vielfach ausgezeichnet, erscheint im Suhrkamp Verlag. - 3 - Max Frisch - Homo faber » >Homo faber< wird der Schweizer Ingenieur Walter Faber beziehungsreich genannt, dem dieser erzählte Bericht in den Mund gelegt ist. Faber ist die vollkommene Verkörperung der technischen Existenz, die sich vor dem Zufall und dem Schicksal sicher glaubt. Diesen Faber, der das fünfzigste Lebensjahr schon überschritten hat, lässt Frisch systematisch mit der außertechnischen Welt, dem Irrationalen, zusammenstoßen. Faber bleibt davon zunächst unerschüttert: die Notlandung seines Flugzeugs in der Wüste, der Selbstmord seines ehemaligen Freundes im Dschungel von Mexiko - das bringt sein rational zementiertes Weltbild nicht ins Wanken. Ernsthaft wird es erst bedroht, als Faber durch die Ereignisse zu einem Rechenschaftsbericht über seine eigene Vergangenheit gezwungen wird. Ein junges Mädchen verliebt sich in ihn. -

T TA/T-T Dissertation LJ1V11 Information Service

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or in black and white paper format.* 4. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or micro fiche but lack clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, all photographs are available in black and white standard 35mm slide format.* ♦For more information about black and white slides or enlarged paper reproductions, please contact the Dissertations Customer Services Department. T TA/T-T Dissertation LJ1V11 Information Service University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 8625189 Caldwell, David GERMAN DOCUMENTARY PROSE OF THE 1970S The Ohio State University Ph.D. -

Michael Bullock Fonds

Michael Bullock fonds Inventory revised by Alan Doyle (2003), Susan Walters (2003), and Tracey Krause (2007) Last revised September 2010 University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Biographical Sketch o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Assorted Poems Series o Collected Poems Series o Prose Series . Lotte Bullock Sub-Series o Plays Series o Essays and Criticism Series o Artwork Series o Works in Translation Series o Correspondence Series o Notes Series o Reviews Series o Melmoth Vancouver Series o Photographs Series o Audiotape Recordings Series o Diaries Series o Biographical Notes Series o Conferences, Lectures, and Readings Series o Promotional Material Series o Financial Records Series o Published Material Series o Miscellaneous Series File List Photographs Catalogue entry (UBC Library catalogue) Fonds Description Michael Bullock fonds. – 1925-2006. 8.32 m of textual records and other materials. Biographical Sketch Michael Bullock was born in 1916 in London, England where he worked for many years as a freelance writer and translator. His prolific, life long writing career was not limited, it seems, by genre, and he was to produce essays, plays, works in translation, prose, and poetry throughout his career. As well as being a prolific writer and translator, Bullock was the founder, and for five years editor, of the British poetry magazine Expression, as well as editor-in-chief of Prism International. Considered a surrealist (he was a founding member of Melmoth Vancouver, originally titled The Vancouver Surrealist Newsletter). Bullock was unafraid to push the limits of creative writing, often blending poems with music and visual art. -

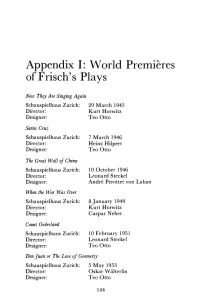

Appendix 1: World Premieres of Frisch's Plays

Appendix 1: World Premieres of Frisch's Plays Now They Are Singing Again Schauspielhaus Zurich: 29 March 1945 Director: Kurt Horwitz Designer: Teo Otto Santa Cru;:; Schauspielhaus Zurich: 7 March 1946 Director: Heinz Hilpert Designer: Teo Otto The Great Wall of China Schauspielhaus Zurich: I 0 October 1946 Director: Leonard Steckel Designer: Andre Perottet von Laban When the War Was Over Schauspielhaus Zurich: 8January 1949 Director: Kurt Horwitz Designer: Caspar Neher Count Oederland Schauspielhaus Zurich: 10 February 1951 Director: Leonard Steckel Designer: Teo Otto Don juan or The Love of Geometry Schauspielhaus Zurich: 5 May 1953 Director: Oskar Wiilterlin Designer: Teo Otto 144 Appendix I 145 The Fire Raisers Schauspie1haus Zurich: 29 March 1958 Director: Oskar Wiilterlin Designer: Max Frisch Andorra Schauspielhaus Zurich: 2, 3, 4 November 1961 Director: Kurt Hirschfeld Designer: Teo Otto Biography. A Game Schauspielhaus Zurich: 1, 2, 3 February 1968 Director: Leopold Lindtberg Designer: Teo Otto Triptych. Three Scenic Panels Centre dramatique de Lausanne: 10 October 1979 Director: Michel Soutter Designer: Jean Lecoultre (German premiere: Akademietheater Vienna: 1 February 1981 Director: Erwin Axer Designer: Ewa Starowieyska) Appendix II: Chronological Table 1911 Born 15 May in Zurich. Father: Franz Bruno Frisch (Architect), Mother: Karolina Bettina (nee Wilder muth). 1924-30 Realgymnasium, Zurich. 1931 Matriculates at Zurich University to read German. 1932 Father dies. Leaves university to work as freelance journalist. 1933 Travels abroad for first time: Prague, Budapest, Belgrade, Istanbul, Athens, Rome. 1934 Jiirg Reinhart. Eine sommerliche Schicksalsfahrt (novel). 1935 First visit to Germany. 1936-41 Reads Architecture at the Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule, Zurich. 1937 Antwort aus der Stille. -

"Bluebeard" and "The Bloody Chamber": the Grotesque of Self-Parody and Self-Assertion Author(S): Kari E

Frontiers, Inc. "Bluebeard" and "The Bloody Chamber": The Grotesque of Self-Parody and Self-Assertion Author(s): Kari E. Lokke Reviewed work(s): Source: Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 10, No. 1 (1988), pp. 7-12 Published by: University of Nebraska Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3345932 . Accessed: 08/05/2012 20:24 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Nebraska Press and Frontiers, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. http://www.jstor.org Bluebeardand The Bloody Chamber: The Grotesqueof Self-Parodyand Self-Assertion Kari E. Lokke Like many fairy tale motifs, the Bluebeardlegend is gro- defenderof the modemsagainst the ancientsin the seventeenth- tesquein essence. This taleof the wealthy,seemingly chivalrous centuryQuerelle des Ancienset des Modernes,trying to com- aristocratwho murdersseven young brides and inters them fort himself and his readerwith this ironic moral to his own in his cellar bringstogether violence and love, perversionand renderingof the Bluebeardtale: -

Max's Frisch's Don Juan

A Study in Translation: Max's Frisch's Don Juan Author: Teresa Marie Behr Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/409 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2006 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. A Study in Translation: By Teresa M. Behr Thesis Directors: Professor Michael Resler, German Department and Associate Professor Paul Doherty, Department of English April 2006 A STUDY IN TRANSLATION: MAX FRISCH’S DON JUAN Introduction 1 I. Overview of Theories of Translation A. Translation Theory before the Twentieth Century 5 B. Translation in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries 17 C. The Practical Application of Translation Theory by Modern Translators 25 II. Background for and Tradition of Don Juan A. Introduction to the Life and Work of Max Frisch 29 B. German-Language Swiss Literature after World War II 31 C. Introduction to Max Frisch’s Don Juan: the Origin of the Myth and Frisch’s Sources 38 III. Max Frisch’s Don Juan A. Summary of the Action 46 B. Don Juan: Or, the Love of Geometry 48 IV. Notes on the Translation and Difficulties Encountered A. Textual Notes 149 B. Difficulties with the Text of Don Juan 153 C. Difficulties Peculiar to German-English Translation 156 Bibliography 165 INTRODUCTION I like languages. It has always made me somewhat sad that I could not simply devote my life to learning one after the other (not that I haven’t thus far made an effort to do so).