Seedlings of William Foster Book II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES Sought the Presidency in 1940

1952 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - HOUSE 1143 ident supply in public life. He was a vision NOMINATION OF HAR~ A. McDONALD, until tomorrow. Wednesday, February ary and a realist, a conservative and a lib TO BE ADMINISTRATOR OF RFC-RE 20, 1952, at 12 o'clock meridian. eral, an independent thinker never afraid of PORT OF A COMMITTEE the unorthodox or the unconventional. "I won't be dropped into a mold. I want to be Mr. MAYBANK. Mr. President, from CONFIRMATION a free spirit," he said. He was as American the Committee on Banking and Curren as the countryside of his n ative Indiana, and cy, I report favorably the nomination of Executive nomination confirmed b~ America could do with more men like Wen Harry A. McDonald, of Michigan, to be the Senate, February 19 (legislative day dell Willkie. Administrator of the Reconstruction of January 10), 1952: CANAL ZONE . Mr. BRIDGES. Mr. President, I am Finance Corporation. The nomination was ordered reported by the committee Rowland Keough Hazard, of Rhode Island, glad to associate myself with the Sen to be district attorney for the Canal Zone. ator from Illinois in his remarks com by a vote of 7 to 3. The PRESIDING OFFICER <Mr. LEH mendatory of Wendell Willkie. It was MAN in the chair). The nomination will my privilege to be an enthusiastic and b~ received and placed on the Executive active supporter of Mr. Willkie when he Calendar. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES sought the Presidency in 1940. My friendship with him continued until his TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 19, 1952 EX:i:CUTIVE REPORTS OF COMMITTEES death, and I agree with the Senator from The House met at 12 o'clock noon. -

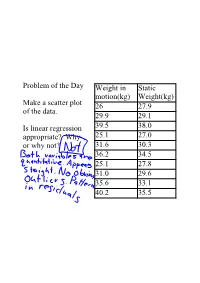

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Major Leagues Are Enjoying Great Wealth of Star

MAJOR LEAGUES ARE ENJOYING GREAT WEALTH OF STAR FIRST SACKERS : i f !( Major League Leaders at First Base l .422; Hornsby Hit .397 in the National REMARKABLE YEAR ^ AMERICAN. Ken Williams of Browns Is NATIONAL. Daubert and Are BATTlMi. Still Best in Hitting BATTING. Pipp Play-' PUy«,-. club. (1. AB. R.11. HB SB.PC. Player. Club. G. AB. R. H. I1R. SB. PC. Slsler. 8*. 1 182 SCO 124 233 7 47 .422 iit<*- Greatest Game of Cobb. r>et 726 493 89 192 4 111 .389 Home Huns. 105 372 52 !4rt 7 7 .376 Sneaker, Clev. 124 421 8.1 ir,« 11 8 .375 liar foot. St. L. 40 5i if 12 0 0 .375 I'll 11 Lives. JlHTneyt Det 71184 33 67 0 2 .364 Russell, Pitts.. 48 175 43 05 12 .4 .371 l.-llmunn, D«t. 118 474! #2 163 21 8 .338 Konseca, Cln. (14 220 39 79 2 3 .859 Hugh, N. Y 34 84 14 29 0 0 .347.! George Sisler of the Browne is the Stengel, N. V.. 77 226 42 80 6 5 .354 Woo<lati, 43 108 17 37 0 0 H43 121 445 90 157 13 6 .35.4 N. Y Ill 3?9 42 121 1 It .337 leading hitter of the American League 133 544 100 191 3 20 .351 IStfcant. .110 418 52 146 11 5 .349 \ an Glider, St. I.. 4<"» 63 15 28 2 0 .337 with a mark of .422. George has scored SISLER STANDS A I TOP 'i'obln, fit J 188 7.71 114 182 11 A .336 Y 71 190 34 66 1 1 .347 Ftagsloart, Det 87 8! 18 27 8 0 .833 the most runs. -

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

High Resolution

WEDNESDAY APRIL 21, 2021 RAMADAN 9, 1442 VOL.14 NO. 5238 QR 2 Fajr: 3:45 am Dhuhr: 11:33 am P ARTLY CLOUDY Asr: 3:02 pm Maghrib: 6:02 pm HIGH : 37°C LOW : 25 °C Isha: 7:32 pm RAMADAN TIMING World 7 Business 8 Sports 12 TODAY TOMORROW IFTAR IMSAK EU regulator backs ‘Many opportunities Infantino against Super J&J despite rare for Polish firms in Qatar’s League; anger & resistance 6:02PM 3:44AM blood clot link digital market’ mount in England Qatar expresses grave concern over recent Chad 37% adults got at least 1 developments COVID vaccine jab: MoPH 1,296,520 COVID-19 vaccine doses have been administered so far TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK DOHA QNA ALMOST 37 percent of people aged DOHA Mosques to open 20 mins 16 years and above have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 Qatar on Tuesday expressed vaccine since the start of Qatar’s great concern over the latest before second azan for National COVID-19 Vaccination developments in the Republic of Programme, the Ministry of Public Chad and the murder of Chad’s Friday prayer, says Awqaf Health (MoPH) has announced. President Idriss Deby. “36.9 percent of the eligible pop- In a statement, the Ministry TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK pandemic, it was decided to open ulation has now received at least one of Foreign Affairs renewed its DOHA the doors of mosques to receive dose of the vaccine,” the MoPH said rejection of violence regardless worshipers for the Friday sermon in a tweet. of motives and reasons. -

William Prince

William Prince by Ted A Griffin Table Of Contents Register Report for William Prince 1 Kinship Report for William Prince 76 Index 102 ii Register Report for William Prince Generation 1 1. WILLIAM1 PRINCE was born about 1788 in Candys Creek, Mcminniville, Tennessee, USA. He died in 1850 in Lawrence, Kentucky, United States. He married (1) LAURIE FYFFE in 1798. He married (2) RACHEL MURPHY about 1810 in Russell, Virginia, USA. She was born about 1784 in Tennessee, USA. She died in Lawrence, Kentucky, United States. Notes for William Prince: We know that William Prince was named William D. Prince as the 1850 census of Habersham county shows this, and also the 1850 delinquent tax list of Habersham shows the same name. The 1850 Murray county GA census shows William enumerated without his middle initial, but there is no doubt it is the same family (with a few unsurprising discrepancys) that appears in 1850 Habersham. As Joseph Prince owned land in Murray county GA in 1850, it is certainly likely that William was residing on that land once he left Habersham. (Phil Prince <[email protected]>) Notes for Laurie Fyffe: There is no evidence that this is correct. It is most likely that Laurie Fyffe married some other William Prince. Notes for Rachel Murphy: Rachel filed for divorce on Dec 21, 1835 stating that she and William had moved back to Lawrence Co. abt 1828 and in 1829 he had deserted her and taken up with Arty Mullins. (According to my Great Aunt Emma Prince Thompson, Carter Prince's Grandmother was a Gregor. -

16 Lc 39 1378S

16 LC 39 1378S The Senate Committee on Transportation offered the following substitute to HR 1052: A RESOLUTION 1 Dedicating certain portions of the state highway system; and for other purposes. 2 PART I 3 WHEREAS, our nation's security continues to rely on patriotic men and women who put 4 their personal lives on hold in order to place themselves in harm's way to protect the 5 freedoms that all United States citizens cherish; and 6 WHEREAS, Corporal Matthew Britten Phillips played a vital role in leadership and 7 demonstrated a deep personal commitment to the welfare of the citizens of Georgia; and 8 WHEREAS, Corporal Phillips was born on April 13, 1981, the beloved son of Michael and 9 Freida Phillips, and attended West Hall High School in Gainesville, Georgia; and 10 WHEREAS, he served as a guardian of this nation's freedom and liberty with the United 11 States Armed Forces, valiantly and courageously protecting his fellow Americans with the 12 173rd Airborne Brigade; and 13 WHEREAS, Corporal Phillips made the ultimate sacrifice during the Battle of Wannat when 14 his unit was ambushed by the Taliban; and 15 WHEREAS, Corporal Phillips embodied the spirit of service, willing to find meaning in 16 something greater than himself, and it is abundantly fitting and proper that this remarkable 17 and distinguished American be recognized appropriately by dedicating an intersection in his 18 memory. 19 PART II 20 WHEREAS, the State of Georgia lost one of its finest citizens and most dedicated law 21 enforcement officers with the tragic passing -

2019 JUNO Award Nominees

2019 JUNO Award Nominees JUNO FAN CHOICE AWARD (PRESENTED BY TD) Alessia Cara Universal Avril Lavigne BMG*ADA bülow Universal Elijah Woods x Jamie Fine Big Machine*Universal KILLY Secret Sound Club*Independent Loud Luxury Armada Music B.V.*Sony NAV XO*Universal Shawn Mendes Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal SINGLE OF THE YEAR Growing Pains Alessia Cara Universal Not A Love Song bülow Universal Body Loud Luxury Armada Music B.V.*Sony In My Blood Shawn Mendes Universal Pray For Me The Weeknd, Kendrick Lamar Top Dawg Ent*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR Camila Camila Cabello Sony Invasion of Privacy Cardi B Atlantic*Warner Red Pill Blues Maroon 5 Universal beerbongs & bentleys Post Malone Universal ASTROWORLD Travis Scott Sony ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Darlène Hubert Lenoir Simone* Select These Are The Days Jann Arden Universal Shawn Mendes Shawn Mendes Universal My Dear Melancholy, The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Outsider Three Days Grace RCA*Sony ARTIST OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Alessia Cara Universal Michael Bublé Warner Shawn Mendes Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal Tory Lanez Interscope*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR (PRESENTED WITH APPLE MUSIC) Arkells Arkells*Universal Chromeo Last Gang*eOne Metric Metric Music*Universal The Sheepdogs Warner Three Days Grace RCA*Sony January 29, 2019 Page 1 of 9 2019 JUNO Award Nominees -

2020 Topps Archives Signatures Baseball Checklist

2020 Topps Archives Signatures Retired Baseball Player List - 110 Players Al Oliver David Cone Jim Rice Mike Schmidt Tim Lincecum Alex Rodriguez David Justice Jim Thome Mo Vaughn Tim Raines Andre Dawson David Ortiz Joe Mauer Moises Alou Tino Martinez Andres Galaragga David Wright Joe Pepitone Nolan Ryan Todd Helton Andruw Jones Dennis Eckersley John Smoltz Nomar Garciaparra Tom Glavine Andy Pettitte Dennis Martinez Johnny Bench Ozzie Smith Tony Perez Barry Larkin Don Mattingly Johnny Damon Randy Johnson Vern Law Barry Zito Dwight Gooden Jorge Posada Reggie Jackson Vladimir Guerrero Bartolo Colon Edgar Martinez Jose Canseco Rey Ordonez Wade Boggs Benito Santiago Eric Chavez Juan Gonzalez Rickey Henderson Will Clark Bernie Carbo Eric Davis Juan Marichal Roberto Alomar Bernie Williams Frank Thomas Ken Griffey Jr. Robin Yount Bert Blyleven Fred McGriff Kerry Wood Rod Carew Bob Gibson George Foster Lou Brock Roger Clemens Bronson Arroyo Gorman Thomas Luis Gonzalez Rollie Fingers Cal Ripken Jr. Hank Aaron Luis Tiant Rondell White Carl Yazstremski Hideki Matsui Magglio Ordonez Ruben Sierra Carlton Fisk Ichiro Manny Sanguillen Ryan Howard CC Sabathia Ivan Rodriguez Mariano Rivera Ryne Sandberg Cecil Fielder Jason Varitek Mark Grace Sandy Alomar Jr. Chipper Jones Jay Buhner Mark McGwire Sandy Koufax Cliff Floyd Jeff Bagwell Mark Teixeira Sean Casey Dale Murphy Jeff Cirillo Maury Willis Shawn Green Darryl Strawberry Jerry Remy Miguel Tejeda Steve Carlton Dave Stewart Jim Abbott Mike Mussina Steve Rogers 2020 Topps Archives Signatures Baseball Player List - 110 Players. -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

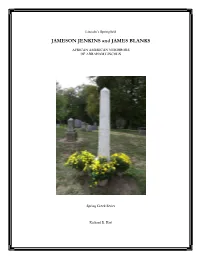

JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS

Lincoln’s Springfield JAMESON JENKINS and JAMES BLANKS AFRICAN AMERICAN NEIGHBORS OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN Spring Creek Series Richard E. Hart Jameson Jenkins’ Certificate of Freedom 1 Recorded With the Recorder of Deeds of Sangamon County, Illinois on March 28, 1846 1 Sangamon County Recorder of Deeds, Deed Record Book 4, p. 21, Deed Book AA, pp. 284-285. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks Front Cover Photograph: Obelisk marker for graves of Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks in the “Colored Section” of Oak Ridge Cemetery, Springfield, Illinois. This photograph was taken on September 30, 2012, by Donna Catlin on the occasion of the rededication of the restored grave marker. Back Cover Photograph: Photograph looking north on Eighth Street toward the Lincoln Home at Eighth and Jackson streets from the right of way in front of the lot where the house of Jameson Jenkins stood. Dedicated to Nellie Holland and Dorothy Spencer The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum is a not-for-profit organization founded in February, 2006, for the purpose of gathering, interpreting and exhibiting the history of Springfield and Central Illinois African Americans life in the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. We invite you to become a part of this important documentation of a people’s history through a membership or financial contribution. You will help tell the stories that create harmony, respect and understanding. All proceeds from the sale of this pamphlet will benefit The Springfield and Central Illinois African American History Museum. Jameson Jenkins and James Blanks: African American Neighbors of Abraham Lincoln Spring Creek Series. -

Educational Implications Busisiwe Helen Baloyi

BLACK COMMUNITY ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE DISABLED EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS by BUSISIWE HELEN BALOYI Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION in the subject PSYCHOLOGY OF EDUCATION atthe UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Promotor: PROF A C LESSING 31 January 1997 DECLARATION Student number: 849-871-7 I declare that BLACK COMMUNITY ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE DISABLED - EDUCATIONAL IMPLICATIONS is my own work and that. all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. 31 Ja11ua"j /tf'f1 SIGNATURE DATE (MISS) B H BALOYI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IN ALL THAT YOU DO GIVE THANKS TO THE LORD "I give thanks to Him (Jesus Christ) who has granted me permission. He has judged and counted me faithful and trustworthy appointing me to do this work" (1Timothy1:12). • I am dedicating this thesis to my dear children, Sipho (Bournny) and Nomsa (Jacqueline), for their encouragement became pillars of strength in my work. * My dear parents, Efric and Alinah, for their interest and encouragement in my work. In particular I wish to express my sincere gratitude to: 1. Professor A.C. Lessing, to whom I am indebted for her expert guidance. A hard worker, working in a most challenging way. I have attained more knowledge through her. 2. Professor M.W. de Witt, for her knowledge and interest in assisting me to complete this work. 3. Dr J.P. Sammons for her good typing of this thesis. She was always zealous to assist. Blessed are people with patience without complaints. 4. Mrs M.