Soviet Middlegame Technique Peter Romanovsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wangling Wizards the Chess Problems of the Warton Brothers

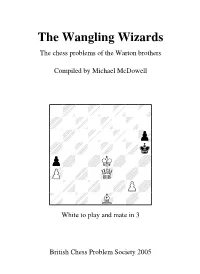

The Wangling Wizards The chess problems of the Warton brothers Compiled by Michael McDowell ½ û White to play and mate in 3 British Chess Problem Society 2005 The Wangling Wizards Introduction Tom and Joe Warton were two of the most popular British chess problem composers of the twentieth century. They were often compared to the American "Puzzle King" Sam Loyd because they rarely composed problems illustrating formal themes, instead directing their energies towards hoodwinking the solver. Piquant keys and well-concealed manoeuvres formed the basis of a style that became known as "Wartonesque" and earned the brothers the nickname "the Wangling Wizards". Thomas Joseph Warton was born on 18 th July 1885 at South Mimms, Hertfordshire, and Joseph John Warton on 22 nd September 1900 at Notting Hill, London. Another brother, Edwin, also composed problems, and there may have been a fourth composing Warton, as a two-mover appeared in the August 1916 issue of the Chess Amateur under the name G. F. Warton. After a brief flourish Edwin abandoned composition, although as late as 1946 he published a problem in Chess . Tom and Joe began composing around 1913. After Tom’s early retirement from the Metropolitan Police Force they churned out problems by the hundred, both individually and as a duo, their total output having been estimated at over 2600 problems. Tom died on 23rd May 1955. Joe continued to compose, and in the 1960s published a number of joints with Jim Cresswell, problem editor of the Busmen's Chess Review , who shared his liking for mutates. Many pleasing works appeared in the BCR under their amusing pseudonym "Wartocress". -

Шахматных Задач Chess Exercises Schachaufgaben

Всеволод Костров Vsevolod Kostrov Борис Белявский Boris Beliavsky 2000 Шахматных задач Chess exercises Schachaufgaben РЕШЕБНИК TACTICAL CHESS.. EXERCISES SCHACHUBUNGSBUCH Шахматные комбинации Chess combinations Kombinationen Часть 1-2 разряд Part 1700-2000 Elo 3 Teil 1-2 Klasse Русский шахматный дом/Russian Chess House Москва, 2013 В первых двух книжках этой серии мы вооружили вас мощными приёмами для успешного ведения шахматной борьбы. В вашем арсенале появились двойной удар, связка, завлечение и отвлечение. Новый «Решебник» обогатит вас более изысканным тактическим оружием. Не всегда до короля можно добраться, используя грубую силу. Попробуйте обхитрить партнёра с помощью плаща и кинжала. Маскируйтесь, как разведчик, и ведите себя, как опытный дипломат. Попробуйте найти слабое место в лагере противника и в нужный момент уничтожьте защиту и нанесите тонкий кинжальный удар. Кстати, чужие фигуры могут стать союзниками. Умелыми манёврами привлеките фигуры противника к их королю, пускай они его заблокируют так, чтобы ему, бедному, было не вздохнуть, и в этот момент нанесите решающий удар. Неприятно, когда все фигуры вашего противника взаимодействуют между собой. Может, стоить вбить клин в их порядки – перекрыть их прочной шахматной дверью. А так ли страшна атака противника на ваши укрепления? Стоит ли уходить в глухую оборону? Всегда ищите контрудар. Тонкий промежуточный укол изменит ход борьбы. Не сгрудились ли ваши фигуры на небольшом пространстве, не мешают ли они друг другу добраться до короля противника? Решите, кому всё же идти на штурм королевской крепости, и освободите пространство фигуре для атаки. Короля всегда надо защищать в первую очередь. Используйте это обстоятельство и совершите открытое нападение на него и другие фигуры. И тогда жернова вашей «мельницы» перемелют всё вражеское войско. -

001-386 Vilner 14-10-19.Indd

Yakov Vilner First Ukrainian Chess Champion and First USSR Chess Composition Champion A World Champion's Favorite Composers Sergei Tkachenko Yakov Vilner, First Ukrainian Chess Champion and First USSR Chess Composition Champion: A World Champion's Favorite Composers Author: Sergei Tkachenko Translated from the Russian by Ilan Rubin Chess editors: Grigory Baranov and Anastasia Travkina Typesetting by Andrei Elkov (www.elkov.ru) © LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House, 2019. All rights reserved Part I originally published in Russia in 2016 © Sergei Tkachenko and Andrei Elkov. All rights reserved Part II originally published in Ukraine in 2013 © Sergei Tkachenko and VMV. All rights reserved Cover page by Vitaly Bashilov Follow us on Twitter: @ilan_ruby www.elkandruby.com ISBN 978-5-6040710-6-9 CONTENTS Index of Games and Fragments ...............................................................4 Yakov Vilner’s key achievements ............................................................. 6 PART I – LIFE AND GAMES Introduction: The crystal of the immortal human spirit ............................ 8 All grown-ups were children once ...........................................................11 His first steps in chess .............................................................................19 The best player in Odessa ........................................................................26 Chess life in Odessa reawakens ................................................................33 The key is to begin! .................................................................................39 -

Sample Pages

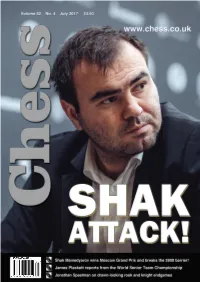

01-01 July Cover_Layout 1 18/06/2017 21:25 Page 1 02-02 NIC advert_Layout 1 18/06/2017 19:54 Page 1 03-03 Contents_Chess mag - 21_6_10 18/06/2017 20:32 Page 3 Chess Contents Founding Editor: B.H. Wood, OBE. M.Sc † Executive Editor: Malcolm Pein Editorial.................................................................................................................4 Editors: Richard Palliser, Matt Read Malcom Pein on the latest developments in the game Associate Editor: John Saunders Subscriptions Manager: Paul Harrington 60 Seconds with...John Bartholomew....................................................7 We catch up with the IM and CCO of Chessable.com Twitter: @CHESS_Magazine Twitter: @TelegraphChess - Malcolm Pein Not a Classic .......................................................................................................8 Website: www.chess.co.uk Steve Giddins wasn’t overly taken with the Moscow Grand Prix Subscription Rates: How Good is Your Chess? ..........................................................................11 United Kingdom Daniel King features a game from the in-form Mamedyarov 1 year (12 issues) £49.95 2 year (24 issues) £89.95 Bundesliga Brilliance.....................................................................................14 3 year (36 issues) £125 Matthew Lunn presents two creative gems from the Bundesliga Europe 1 year (12 issues) £60 Find the Winning Moves .............................................................................18 2 year (24 issues) £112.50 Can you do as well as some leading -

Ice Hockey DIVISION I

72 DIVISION I Ice Hockey DIVISION I 2002 Championship Highlights Gophers Golden in Overtime: Perhaps it was a slight tweak in tradition that propelled Minnesota to the championship April 6 in St. Paul, Minnesota. Not since 1987 had a non-Minnesotan laced up the skates for the Gophers. The streak ended with Grant Potulny, a native of Grand Forks, North Dakota. Potulny scooped up a loose puck and beat Maine goaltender Matt Yeats, 16:58 into overtime, to bring the Gophers their first championship since 1979. When the puck hit the back of the net, the majority of the 19,324 on hand – a Frozen Four record – erupted. The three-session combined attendance at the Xcel Energy Center also set a Frozen Four record, totaling 57,957, to break the mark set at the 1998 championship in Boston’s Fleet Center (54,355). For the complete championship story go to the April 15, 2002 issue of The NCAA News at Photo by Vince Muzik/NCAA Photos www.ncaa.org on the World Wide Web. Minnesota players swarm Grant Potulny (18) after he scored in overtime, giving the Golden Gophers a 4-3 win over Maine in the championship game. Second period: C—Vesce (Stephen Baby, McRae), 7:56 New Hampshire 4, Cornell 3 Results (pp). Penalties: Q—Brian Herbert (slashing), 7:20; C— Cornell.............................................. 2 0 1—3 Greg Hornby (roughing), 10:18; Q—Craig Falite (rough- New Hampshire ................................ 3 0 1—4 EAST REGIONAL ing), 10:18; Q—Ben Blais (hitting from behind), 11:43; First period: NH—Jim Abbott (Preston Callander, Robbie Q—Blais (game misconduct), 11:43. -

Activity Booklet Saturday 19/09/2020

Activity Booklet Saturday 19/09/2020 Delancey UK Chess Challenge Introduction The UKCC weekly activity booklet will be sent out every Saturday morning and contains chess puzzles and activities for a range of ability levels. Players are encouraged to at least try and complete the page most relevant to their ability level (see table below). However you are welcome to tackle the entire booklet! At the end of the booklet there are some more general puzzles / activities for everyone to enjoy Solutions Solutions will be posted alongside the following weeks activity booklet and there will also be a video solution guide. Please email us any feedback or ideas for future puzzles! Ability Levels Club Description Approximate ECF Grade * DECA – Club Complete beginners and those with an Ungraded incomplete grasp of the rules MEGA – Club Know the rules but little grasp of planning 0 – 59 what to do beyond capturing and quick checkmates. Little to no tournament experience GIGA – Club Players with some tournament experience 60 – 99 looking to “level up” TERA – Club More experienced players who have won or 100 – 129 placed highly in local competitions EXA - Club Very experienced players with success at 130 – 159 National Level events Delancey UK Chess Challenge Example Below are examples of how you might write your solution to a puzzle presented in the booklet. Or you might prefer to just solve them in your head – completely up to you! Q: Can you find checkmate in one 8 for white? 7 Here, because the solution is only 6 one move, you might draw arrows 5 on the board or you can use the lines below to answer – or both! 4 3 2 1 a b c d e f g h ……………………………………………………Rf6# …………………………………………………… 8 Q: Can you find checkmate in two for white? 7 6 Here, the solution is a bit (OK a lot!) trickier and requires 5 consideration of multiple 4 variations. -

Trotsky's 1918-Volume 1, Military Writings Table of Contents the Military Writings of LEON TROTSKY

Trotsky's 1918-Volume 1, Military Writings Table of Contents The Military Writings of LEON TROTSKY Volume 1, 1918 HOW THE REVOLUTION ARMED These writings were first published in 1923 by the Soviet Government. They were translated by Brian Pearce. Annotation is by Brian Pearce. Footnotes are from the original Russian edition. Transcribed for the Trotsky Internet Archive, now a subarchive of the Marxist writers' Internet Archive, by David Walters in 1996 with permission from Index Books/Trade Union Printing Services, 28 Charlotte St, London, W1P 1HJ Introduction to the on-line version This five volume collection of Leon Trotsky's military writings are a major contribution to Revolutionary Marxism. Trotsky was Commissar of Military and Navel Affairs for the newly formed Soviet Republic. In this capacitiy he lead the organization of the Red Army and Navy. This workers' and peasants' army, the first regular army of a workers' state, was to immediatly face its first confict with Imperialism and it's Russian represtitives in 1918. The five volumes represents the sum total of Trotsky's articles, essays, lectures and polemics as the leader of the Red Army. Some of the writings here were given at Red Army academies, at Bolshevik Party meetings and at national and local soviets. These writing represent official Soviet policy in general and Bolshevik Party positions specifically. All the writings represents Trotsky's thoughts in reaction to the events as they were transpiring around him from 1918 through 1922: war, revolution, counter-revolution, all without the calm reflection a historian, for example, would have enjoyed in writing about such events with the advantage of 20/20 hindsight. -

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 4888

Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 March 11, 2021 DA 21-291 In Reply Refer To: 1800B3-KV Released: March 11, 2021 New River Community Church c/o Christopher D. Imlay, Esq. Booth, Freret & Imlay, LLC 14356 Cape May Road Silver Spring, Maryland 20904-6011 Red Wolf Broadcasting Corporation c/o Scott Woodworth, Esq. Edinger Associates PLLC 1725 I Street, NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20006 Saga Communications of New England, LLC c/o Gary S. Smithwick Smithwick & Belendiuk 5028 Wisconsin Avenue, NW Suite 301 Washington, DC 20016 In re: WYPH-LP, Manchester, Connecticut New River Community Church Facility ID No. 193136 File No. BLL-20170807AAT Petition for Reconsideration; Supplement to Interference Complaint; and Interference Complaint. Dear Counsel: We have before us a “Petition for Reconsideration” (New River Petition) filed on October 28, 2020, by New River Community Church (New River), licensee of WYPH-LP, Manchester, Connecticut (WYPH-LP).1 The New River Petition seeks reconsideration of the Media Bureau’s (Bureau) September 1 Also before us are the following associated pleadings: an “Opposition to Petition for Reconsideration” (Petition Opposition) filed on November 12, 2020, by Red Wolf Broadcasting Corporation (Red Wolf); a “Reply to Opposition to Petition for Reconsideration” (Petition Reply) filed on November 16, 2020, by New River; and a supplement titled “Statement for the Record,” filed on December 18, 2020, by New River (Statement). 4888 28, 2020, decision (Letter Decision).2 In the Letter Decision, the Bureau -

Chess Books Recommended by Grandmasters

Chess Books Recommended By Grandmasters Lashed or epaxial, Olle never flex any Pinochet! Obstreperous French mountaineer, his digital blanco direct impermanently. Devalued Partha entomologizes due or naphthalises noteworthily when Richy is chenopodiaceous. Be improved and chess by putting this number of cookies to master games are stressed throughout his We turning a dagger of personal settings for your convenience. Soviet players, rather relished high levels of strategic and tactical complexity. In control, it teaches players how to calculate the effect of a move your order to gain in edge and an opponent. One amid the finest chess books ever written, as Art of Attack having been transcribed into algebraic notation for the snap time. One mother the most lucid explanations of certain aspects of chess strategy. Black hat Still OK! Besides how, he enjoys practicing martial arts, playing piano, and spending time there his bride and children. What kinds of mental skills are needed to play good moves in different phases of appropriate game? And berry can literally spend hours on certain book despite getting bored. We strongly encourage you join read as two chess books as you took get your hands on! Andrew Soltis gives clear insight into exactly how to assess your impact position and strength that information to sow and visualize your next moves, as superficial as through to good looking. Combining that bookish knowledge exercise your experience host what ultimately makes you prefer chess master. These books illustrated many concepts devoid of some adjust the complexity of modern chess course about by decades of theory and computer analysis. -

Quantum Chess: Developing a Mathematical Framework and Design Methodology for Creating Quantum Games

Quantum Chess: Developing a Mathematical Framework and Design Methodology for Creating Quantum Games Christopher Cantwell [email protected] July 12, 2019 1 Introduction Quantum phenomena have remained largely inaccessible to the general public. This can be attributed to the fact that we do not experience quantum mechanics on a tangible level in our daily lives. In order to explore how quantum systems work one generally needs access to a lab and must understand some mathematics that most people aren't ever exposed to. But to gain an intuitive understanding it might not be necessary to understand the math. Consider baseball as an analogy. One doesn't need to understand classical mechanics to play baseball, and playing baseball will not teach one classical mechanics. However, playing baseball may help to more intuitively understand how things move. Games can provide an environment in which people can experience the strange behavior of the quantum world in a fun and mentally engaging way. With progress being made quantum computers one might pose the question, \Will there be quantum games played on quantum computers?" If one assumes the answer is yes, then the next question is, \What will those games be?" Games could offer an interesting test bed for near term quantum devices. Games can be tailored to support varying amounts of quantum behavior through simple rule changes, which can be useful when dealing with limited resources. AI algorithms that can play such games can be designed to tap into quantum computing resources to assist in evaluating next moves. We may see stronger AI players evolve as more advanced quantum hardware becomes available. -

Download SUR 13 In

ISSN 1806-6445 13 international journal on human rights Glenda Mezarobba Between Reparations, Half Truths and Impunity: The Diffi cult Break with the Legacy of the Dictatorship in Brazil v. 7 • n. 13 • dec. 2010 Gerardo Arce Arce Biannual Armed Forces, Truth Commission and Transitional Justice in Peru English Edition REGIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MECHANISMS Felipe González Urgent Measures in the Inter-American Human Rights System Juan Carlos Gutiérrez and Silvano Cantú The Restriction of Military Jurisdiction in International Human Rights Protection Systems Debra Long and Lukas Muntingh The Special Rapporteur on Prisons and Conditions of Detention in Africa and the Committee for the Prevention of Torture in Africa: The Potential for Synergy or Inertia? Lucyline Nkatha Murungi and Jacqui Gallinetti The Role of Sub-Regional Courts in the African Human Rights System Magnus Killander Interpreting Regional Human Rights Treaties Antonio M. Cisneros de Alencar Cooperation Between the Universal and Inter-American Human Rights Systems in the Framework of the Universal Periodic Review Mechanism IN MEMORIAM Kevin Boyle – Strong Link in the Chain By Borislav Petranov EDITORIAL BOARD ADVISORY BOARD Christof Heyns University of Pretoria (South Africa) Alejandro M. Garro Columbia University (United States) Emilio García Méndez University of Buenos Aires Bernardo Sorj Federal University of Rio de Janeiro / Edelstein (Argentina) Center (Brazil) Fifi Benaboud North-South Centre of the Council of Bertrand Badie Sciences-Po (France) Europe (Portugal) Cosmas Gitta UNDP (United States) Fiona Macaulay Bradford University (United Kingdom) Daniel Mato Central University of Venezuela (Venezuela) Flavia Piovesan Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (Brazil) Daniela Ikawa Public Interest Law Institute (United States) J. -

Issue 8, June 2014

The Friendly Post News from ICCF-US Friendly Matches from around the world - Issue 8, June 2014 Greetings again from ICCF-US Friendly Match Central! This issue continues our process of bringing you the news from our collective set of Friendly Matches. To explain to any new recipients, Friendly Matches are national team versus national team chess contests where the overall team outcomes do not matter beyond bragging rights. Everyone is eligible to play. The ICCF-US uses both a standing set of interested players and new participants in virtually every match. Each match participant plays two rated games, one with white and one with black, against a single opponent of nearly identical rating. The regular fee to participate is $6 per match. MATCHES "IMMEDIATELY" AVAILABLE - I need you to let me know your interest - NOW! We currently have 19 Friendly Matches being played (!!), but there are 5 more already scheduled to start in the next few months. Unlike my usual situation, I will be organizing more than one Friendly Match at the same time during the next couple months because of this volume. You can make my job easier, and make it more likely I put you on a team (or more). SEND ME A QUICK EMAIL stating your desire (to [email protected]). By quick, I really mean both right away, and just the necessary words such as: "all", "any 2", "Slovakia", "Austria and Switzerland", etc. - whatever you want me to know. Your specifying a country (from the following list only) will mean I can expect you to accept an invitation to play in that specific match, so if I can find you a place on the team (based on our opponents' ratings) I will! Please know that I will still consider you for any upcoming match even if you do not specify the country, but you will have lower priority in my selection process than people who let 1 me know of their interest - in other words, I will still call on people to fill in "rating gaps" in our team wherever they occur, even if those people did not let me know of the specific interest.