24Th Annual Richard A. Harrison Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

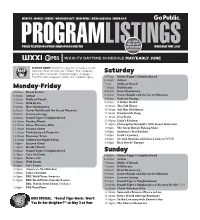

WXXI Program Guide | May 2021

WXXI-TV | WORLD | CREATE | WXXI KIDS 24/7 | WXXI NEWS | WXXI CLASSICAL | WRUR 88.5 SEE CENTER PAGES OF CITY PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFOR WXXI SHOW MAY/EARLY JUNE 2021 HIGHLIGHTS! WXXI-TV DAYTIME SCHEDULE MAY/EARLY JUNE PLEASE NOTE: WXXI-TV’s daytime schedule listed here runs from 6:00am to 7:00pm. The complete prime time television schedule begins on page 2. Saturday The PBS Kids programs below are shaded in gray. 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 6:30am Arthur 7vam Molly of Denali Monday-Friday 7:30am Wild Kratts 6:00am Ready Jet Go! 8:00am Hero Elementary 6:30am Arthur 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 7:00am Molly of Denali 9:00am Curious George 7:30am Wild Kratts 9:30am A Wider World 8:00am Hero Elementary 10:00am This Old House 8:30am Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum 10:30am Ask This Old House 9:00am Curious George 11:00am Woodsmith Shop 9:30am Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood 11:30am Ciao Italia 10:00am Donkey Hodie 12:00pm Lidia’s Kitchen 10:30am Elinor Wonders Why 12:30pm Christopher Kimball’s Milk Street Television 11:00am Sesame Street 1:00pm The Great British Baking Show 11:30am Pinkalicious & Peterrific 2:00pm America’s Test Kitchen 12:00pm Dinosaur Train 2:30pm Cook’s Country 12:30pm Clifford the Big Red Dog 3:00pm Second Opinion with Joan Lunden (WXXI) 1:00pm Sesame Street 3:30pm Rick Steves’ Europe 1:30pm Donkey Hodie 2:00pm Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Sunday 2:30pm Let’s Go Luna! 6:00am Mister Roger’s Neighborhood 3:00pm Nature Cat 6:30am Arthur 3:30pm Wild Kratts 7:00am Molly -

Queering Education: Pedagogy, Curriculum, Policy

Occasional Paper Series Volume 2017 Number 37 Queering Education: Pedagogy, Article 10 Curriculum, Policy May 2017 Queering Education: Pedagogy, Curriculum, Policy Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series Part of the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Sociology Commons, Education Policy Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Recommended Citation (2017). Queering Education: Pedagogy, Curriculum, Policy. Occasional Paper Series, 2017 (37). Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2017/iss37/10 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Paper Series by an authorized editor of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Queering Education: Pedagogy, Curriculum, Policy Introduction Guest Editor: Darla Linville Essays by Denise Snyder Cammie Kim Lin Ashley Lauren Sullivan and Laurie Lynne Urraro Clio Stearns Joseph D. Sweet and David Lee Carlson Julia Sinclair-Palm Stephanie Shelton benjamin lee hicks 7 1 s e 0 i 2 r e S r e p April a P l a n io s a 7 c c 3 O Occasional Paper Series | 1 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... -

The Basque Refugee Children of the Spanish Civil War in the Uk 177

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES THE BASQUE REFUGEE CHILDREN OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR IN THE UK: MEMORY AND MEMORIALISATION by Susana Sabín-Fernández Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2010 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF LAW, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy THE BASQUE REFUGEE CHILDREN OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR IN THE UK: MEMORY AND MEMORIALISATION By Susana Sabín-Fernández A vast body of knowledge has been produced in the field of war remembrance, particularly concerning the Spanish Civil War. However, the representation and interpretation of that conflictual past have been increasingly contested within the wider context of ‘recuperation of historical memory’ which is taking place both in Spain and elsewhere. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S

Terrorizing Gender: Transgender Visibility and the Surveillance Practices of the U.S. Security State A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Mia Louisa Fischer IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Mary Douglas Vavrus, Co-Adviser Dr. Jigna Desai, Co-Adviser June 2016 © Mia Louisa Fischer 2016 Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my family back home in Germany for their unconditional support of my academic endeavors. Thanks and love especially to my Mom who always encouraged me to be creative and queer – far before I knew what that really meant. If I have any talent for teaching it undoubtedly comes from seeing her as a passionate elementary school teacher growing up. I am very thankful that my 92-year-old grandma still gets to see her youngest grandchild graduate and finally get a “real job.” I know it’s taking a big worry off of her. There are already several medical doctors in the family, now you can add a Doctor of Philosophy to the list. I promise I will come home to visit again soon. Thanks also to my sister, Kim who has been there through the ups and downs, and made sure I stayed on track when things were falling apart. To my dad, thank you for encouraging me to follow my dreams even if I chased them some 3,000 miles across the ocean. To my Minneapolis ersatz family, the Kasellas – thank you for giving me a home away from home over the past five years. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Don't Ask, Must Tell—And Other Combinations

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2015 Don't Ask, Must Tell—and Other Combinations Adam M. Samaha Lior Strahilevitz Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Adam Samaha & Lior Strahilevitz, "Don't Ask, Must Tell—and Other Combinations," 103 California Law Review 919 (2015). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Don't Ask, Must Tell- And Other Combinations Adam M. Samaha* & Lior Jacob Strahilevitz** The military's defunct Don't Ask, Don't Tell policy has been studied and debatedfor decades. Surprisingly, the question of why a legal regime would combine these particular rules for information flow has received little attention. More surprisingly still, legal scholars have provided no systemic account of why law might prohibit or mandate asking and telling. While there is a large literature on disclosure and a fragmented literature on questioning, considering either part of the information dissemination puzzle in isolation has caused scholars to overlook key considerations. This Article tackles foundational issues of information policy and legal design, focusing on instances in which asking and telling are either mandated or prohibited by legal rules, legal incentives, or social norms. Although permissive norms for asking and telling seem pervasive in law, the Article shows that each corner solution exists in the American legal system. -

November At-A-Glance *Join Us for a Fall Mystery Marathon on Thursday, November 26 and Friday, November 27

Original Concert Film Screening Fall Mystery Marathon— Series—page 9 Invitation—page 16 pages 17 & 18 Please visit wycc.org/schedule for the most current programming schedule. November at-a-glance *Join us for a Fall Mystery Marathon on Thursday, November 26 and Friday, November 27. Please check the listings for a full schedule. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY* FRIDAY* SATURDAY SUNDAY 6:00 AM Classical Stretch Curious George Curious George The Cat in the Hat The Cat in the Hat 6:30 Body Electric Knows a Lot Knows a Lot About About That! That! (except 11/1) Wai Lana Yoga Ribert & Robert’s Mister Rogers’ 7:00 WonderWorld Neighborhood Sit and Be Fit Angelina Ballerina: Bob the Builder 7:30 The Next Steps Barney & Friends Sid the Science Kid 8:00 Odd Squad 8:30 Wild Kratts Arthur Zula Patrol 9:00 Sesame Street Sesame Street Sesame Street Wunderkind Cyberchase 9:30 Peg + Cat (starting 11/16) Little Amadeus 10:00 Dinosaur Train DragonflyTV Biz Kid$ Mid-American In the Americas with 10:30 Curious George Gardener David Yetman Bob the Builder Garden Smart Pritzker Military 11:00 Presents Victory Garden’s 11:30 Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood (starting 11/16) EdibleFEAST PM P. Allen Smith’s Charlie Rose: 12:00 Super Why! Garden Home The Week Thomas & Friends This Old House Justice and Law 12:30 Weekly The Best of the Sewing with Nancy Well Read Quilting Arts The Beauty of The American Religion & Ethics 1:00 Joy of Painting Oil Painting Woodshop Newsweekly Wyland’s Art Studio Sew It All Between the Lines Fons & Porter’s Beads, Baubles, Hometime Closer to Truth 1:30 with Barry Kibrick Love of Quilting and Jewels Frank Clarke Simply Fit 2 Stitch Joseph Rosendo’s Knitting Daily The Donna The Woodwright’s Second Opinion 2:00 Painting Around the Travelscope Dewberry Show Shop World: China P. -

Transgender and Intersex People in New York's State Prisons

“It’s war in here”: A Report on the Treatment of Transgender and Intersex People in New York State Men’s Prisons First published in 2007 by The Sylvia Rivera Law Project 322 8th Avenue, 3rd Floor New York, NY 10001 www.srlp.org The Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SRLP) works to guarantee that all people are free to self- determine their gender identity and expression, regardless of income or race, and without facing harassment, discrimination, or violence. SRLP is a 501c-3 nonprofit organization. © Copyright 2007 SRLP. Some Rights Reserved. SRLP encourages and grants permission to non-commerically reproduce and distribute this report in whole or in part, and to further grants permission to use this work in whole or in part in the creation of derivative works, provided credit is given author and publisher, and such works are licensed under the same terms. (For more information, see the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/> or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA.) Contents i Introduction 3 ii Scope & Methodology 5 iii Background: Discrimination, Poverty, & Imprisonment 7 iv Daily Realities: Conditions of Confinement for Transgender & Intersex People 15 v Recommendations 32 Appendix A Frequently Asked Questions: Gender Identity & Expression 36 Appendix B Organizations 40 Appendix C Selected Bibliography 41 Appendix D Flow Charts 41 Notes 44 Acknowledgements 49 I INTRODUCTION Since opening in 2002, the Sylvia Rivera Law Project (SRLP) has provided free legal services to over 700 intersex, transgender, and gender non-conforming people.* Our clients are low-income people and people of color who face discrimination in the areas of employment, housing, education, healthcare, and social services. -

Transgender History / by Susan Stryker

u.s. $12.95 gay/Lesbian studies Craving a smart and Comprehensive approaCh to transgender history historiCaL and Current topiCs in feminism? SEAL Studies Seal Studies helps you hone your analytical skills, susan stryker get informed, and have fun while you’re at it! transgender history HERE’S WHAT YOU’LL GET: • COVERAGE OF THE TOPIC IN ENGAGING AND AccESSIBLE LANGUAGE • PhOTOS, ILLUSTRATIONS, AND SIDEBARS • READERS’ gUIDES THAT PROMOTE CRITICAL ANALYSIS • EXTENSIVE BIBLIOGRAPHIES TO POINT YOU TO ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Transgender History covers American transgender history from the mid-twentieth century to today. From the transsexual and transvestite communities in the years following World War II to trans radicalism and social change in the ’60s and ’70s to the gender issues witnessed throughout the ’90s and ’00s, this introductory text will give you a foundation for understanding the developments, changes, strides, and setbacks of trans studies and the trans community in the United States. “A lively introduction to transgender history and activism in the U.S. Highly readable and highly recommended.” SUSAN —joanne meyerowitz, professor of history and american studies, yale University, and author of How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality In The United States “A powerful combination of lucid prose and theoretical sophistication . Readers STRYKER who have no or little knowledge of transgender issues will come away with the foundation they need, while those already in the field will find much to think about.” —paisley cUrrah, political -

Gay Gentrification: Whitewashed Fictions of LGBT Privilege and the New Interest- Convergence Dilemma

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 4 June 2013 Gay Gentrification: Whitewashed Fictions of GBL T Privilege and the New Interest-Convergence Dilemma Anthony Michael Kreis Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Anthony M. Kreis, Gay Gentrification: Whitewashed Fictions of GBL T Privilege and the New Interest- Convergence Dilemma, 31(1) LAW & INEQ. 117 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol31/iss1/4 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. 117 Gay Gentrification: Whitewashed Fictions of LGBT Privilege and the New Interest- Convergence Dilemma Anthony Michael Kreist Introduction In 1986, in the midst of a rapidly spreading HIV/AIDS epidemic,' the United States Supreme Court narrowly held there was no constitutional right to engage in same-sex sodomy.' A mere ten years later, the Court made a sharp departure from its earlier posture towards sexual minorities.' In Romer v. Evans,' the Court struck down a state constitutional amendment that established a wholesale prohibition' of pro-sexual minority rights t. J.D., Washington & Lee University School of Law, B.A., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Ph.D Candidate, University of Georgia School of Public and International Affairs. I am grateful for the inspiration of Professor Julian Bond of the University of Virginia for sparking my interest in intersectionality. I am also thankful to Robin Fretwell Wilson of Washington & Lee for the opportunity to meaningfully engage the public policy of marriage equality legislation with two groups of Religious Liberty scholars led by herself and Douglas Laycock of the University of Virginia. -

<<< Peter Max Lawrence >>>

Peter Max Lawrence [email protected] petermaxlawrence.com SOLO EXHIBITIONS Return of the Yeti, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 The Umpire Strikes Back, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 Beyond Say, Subrosa Space, Athens, Greece, 2018 October Surprise, Jernquist Studio, Brooklyn, NY 2016 In With The Old & Out With The New - New Lofts Art Gallery, Stockton, KS 2015 iNtheStudioAgain&Again&again, one2one, Lucas, KS 2014 Sell Out | Spikes, San Francisco, CA 2013 The Indelible Sulk | Mission: Comics & Art, San Francisco, CA 2013 Magickal Marvels: Ethos, Mythos, and Pathos | James C. Hormel LGBT Center - San Francisco Public Library 2012 The Ghost Show | Gallerí Klósett | Reykjavík, Iceland 2012 At War: Truong Tran & Peter Max Lawrence | SOMArts, San Francisco, CA 2012 Here Comes The Rain | Her Majesty's Secret Beekeeper, San Francisco CA 2011 Prey for Them | Little Bird, San Francisco CA 2011 The Paper Trail | Whiskey Thieves, San Francisco, CA 2010 The Sweet Stink of Stigma, Magnet, San Francisco, CA, 2010 Midnight Moth & Bug Issue #1 vol.3, The Tiny Gallery | Big Think Studios, San Francisco CA 2009 The Innocent Culprit | Whiskey Thieves, San Francisco, CA , 2007 Addicted to Applause | Diego Rivera Gallery, San Francisco, CA , 2007 Contemporary Dilemmas for the Ancient Gods | Magnet, San Francisco, CA, 2006 The Woman of Willendorf and Worldy other Wonders | The Austin Law Group, San Francisco, CA , 2006 Art Span, Open Studios, San Francisco, CA, 2006 Sacred Monsters | Leedy-Voulkos