Nafional Fann Radio Forum on CBC Radio Eleanor Beattie a Thesis the Department Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Franklin Carmichael's Representation of The

TRANSCENDENTAL NATURE AND CANADIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY: FRANKLIN CARMICHAEL’S REPRESENTATION OF THE CANADIAN LANDSCAPE by NICOLE MARIE MCKOWEN Submitted to the Faculty Graduate Division College of Fine Arts Texas Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2019 TRANSCENDENTAL NATURE AND CANADIAN NATIONAL IDENTITY: FRANKLIN CARMICHAEL’S REPRESENTATION OF THE CANADIAN LANDSCAPE Thesis Approved: ______________________________________________________________________________ Major Professor, Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Kay and Velma Kimbell Chair of Art History ______________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Frances Colpitt, Deedie Rose Chair of Art History ______________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Meredith Munson, Lecturer, Art History at University of Texas, Arlington ______________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Joseph Butler, Associate Dean for the College of Fine Arts Date ii iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my committee chair Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite and my committee members Dr. Frances Colpitt and Dr. Meredith Munson for their time and guidance throughout the writing of this thesis. I am also grateful to all of the faculty of the Art History Division of the School of Art at Texas Christian University, Dr. Babette Bohn, Dr. Lori Diel, and Dr. Jessica Fripp, for their support of my academic pursuits. I extend my warmest thanks to Catharine Mastin for her support of my research endeavors and gratefully recognize archivist Philip Dombowsky at the National Gallery of Canada, archivist Linda Morita and registrar Janine Butler at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, and the archivists at the Library and Archives Canada for their enthusiastic aid throughout my research process. Finally, I am indebted to my husband and family, my champions, for their unwavering love and encouragement. -

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's Annual Report For

ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 Valuable Canadian Innovative Complete Creative Invigorating Trusted Complete Distinctive Relevant News People Trust Arts Sports Innovative Efficient Canadian Complete Excellence People Creative Inv Sports Efficient Culture Complete Efficien Efficient Creative Relevant Canadian Arts Renewed Excellence Relevant Peopl Canadian Culture Complete Valuable Complete Trusted Arts Excellence Culture CBC/RADIO-CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 2001-2002 at a Glance CONNECTING CANADIANS DISTINCTIVELY CANADIAN CBC/Radio-Canada reflects Canada to CBC/Radio-Canada informs, enlightens Canadians by bringing diverse regional and entertains Canadians with unique, and cultural perspectives into their daily high-impact programming BY, FOR and lives, in English and French, on Television, ABOUT Canadians. Radio and the Internet. • Almost 90 per cent of prime time This past year, • CBC English Television has been programming on our English and French transformed to enhance distinctiveness Television networks was Canadian. Our CBC/Radio-Canada continued and reinforce regional presence and CBC Newsworld and RDI schedules were reflection. Our audience successes over 95 per cent Canadian. to set the standard for show we have re-connected with • The monumental Canada: A People’s Canadians – almost two-thirds watched broadcasting excellence History / Le Canada : Une histoire CBC English Television each week, populaire enthralled 15 million Canadian delivering 9.4 per cent of prime time in Canada, while innovating viewers, nearly half Canada’s population. and 7.6 per cent share of all-day viewing. and taking risks to deliver • The Last Chapter / Le Dernier chapitre • Through programming renewal, we have reached close to 5 million viewers for its even greater value to reinforced CBC French Television’s role first episode. -

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (AZ Listing by Episode Title. Prices Include

CBC IDEAS Sales Catalog (A-Z listing by episode title. Prices include taxes and shipping within Canada) Catalog is updated at the end of each month. For current month’s listings, please visit: http://www.cbc.ca/ideas/schedule/ Transcript = readable, printed transcript CD = titles are available on CD, with some exceptions due to copyright = book 104 Pall Mall (2011) CD $18 foremost public intellectuals, Jean The Academic-Industrial Ever since it was founded in 1836, Bethke Elshtain is the Laura Complex London's exclusive Reform Club Spelman Rockefeller Professor of (1982) Transcript $14.00, 2 has been a place where Social and Political Ethics, Divinity hours progressive people meet to School, The University of Chicago. Industries fund academic research discuss radical politics. There's In addition to her many award- and professors develop sideline also a considerable Canadian winning books, Professor Elshtain businesses. This blurring of the connection. IDEAS host Paul writes and lectures widely on dividing line between universities Kennedy takes a guided tour. themes of democracy, ethical and the real world has important dilemmas, religion and politics and implications. Jill Eisen, producer. 1893 and the Idea of Frontier international relations. The 2013 (1993) $14.00, 2 hours Milton K. Wong Lecture is Acadian Women One hundred years ago, the presented by the Laurier (1988) Transcript $14.00, 2 historian Frederick Jackson Turner Institution, UBC Continuing hours declared that the closing of the Studies and the Iona Pacific Inter- Acadians are among the least- frontier meant the end of an era for religious Centre in partnership with known of Canadians. -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area. -

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism

John Boyle, Greg Curnoe and Joyce Wieland: Erotic Art and English Canadian Nationalism by Matthew Purvis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Matthew Purvis i Abstract This dissertation concerns the relation between eroticism and nationalism in the work of a set of English Canadian artists in the mid-1960s-70s, namely John Boyle, Greg Curnoe, and Joyce Wieland. It contends that within their bodies of work there are ways of imagining nationalism and eroticism that are often formally or conceptually interrelated, either by strategy or figuration, and at times indistinguishable. This was evident in the content of their work, in the models that they established for interpreting it and present in more and less overt forms in some of the ways of imagining an English Canadian nationalism that surrounded them. The dissertation contextualizes the three artists in the terms of erotic art prevalent in the twentieth century and makes a case for them as part of a uniquely Canadian mode of decadence. Constructing my case largely from the published and unpublished writing of the three subjects and how these played against their reception, I have attempted to elaborate their artistic models and processes, as well as their understandings of eroticism and nationalism, situating them within the discourses on English Canadian nationalism and its potentially morbid prospects. Rather than treating this as a primarily cultural or socio-political issue, it is treated as both an epistemic and formal one. -

1976-77-Annual-Report.Pdf

TheCanada Council Members Michelle Tisseyre Elizabeth Yeigh Gertrude Laing John James MacDonaId Audrey Thomas Mavor Moore (Chairman) (resigned March 21, (until September 1976) (Member of the Michel Bélanger 1977) Gilles Tremblay Council) (Vice-Chairman) Eric McLean Anna Wyman Robert Rivard Nini Baird Mavor Moore (until September 1976) (Member of the David Owen Carrigan Roland Parenteau Rudy Wiebe Council) (from May 26,1977) Paul B. Park John Wood Dorothy Corrigan John C. Parkin Advisory Academic Pane1 Guita Falardeau Christopher Pratt Milan V. Dimic Claude Lévesque John W. Grace Robert Rivard (Chairman) Robert Law McDougall Marjorie Johnston Thomas Symons Richard Salisbury Romain Paquette Douglas T. Kenny Norman Ward (Vice-Chairman) James Russell Eva Kushner Ronald J. Burke Laurent Santerre Investment Committee Jean Burnet Edward F. Sheffield Frank E. Case Allan Hockin William H. R. Charles Mary J. Wright (Chairman) Gertrude Laing J. C. Courtney Douglas T. Kenny Michel Bélanger Raymond Primeau Louise Dechêne (Member of the Gérard Dion Council) Advisory Arts Pane1 Harry C. Eastman Eva Kushner Robert Creech John Hirsch John E. Flint (Member of the (Chairman) (until September 1976) Jack Graham Council) Albert Millaire Gary Karr Renée Legris (Vice-Chairman) Jean-Pierre Lefebvre Executive Committee for the Bruno Bobak Jacqueline Lemieux- Canadian Commission for Unesco (until September 1976) Lope2 John Boyle Phyllis Mailing L. H. Cragg Napoléon LeBlanc Jacques Brault Ray Michal (Chairman) Paul B. Park Roch Carrier John Neville Vianney Décarie Lucien Perras Joe Fafard Michael Ondaatje (Vice-Chairman) John Roberts Bruce Ferguson P. K. Page Jacques Asselin Céline Saint-Pierre Suzanne Garceau Richard Rutherford Paul Bélanger Charles Lussier (until August 1976) Michael Snow Bert E. -

151 Ways to Get CE Credits 2018

View metadata,citationandsimilarpapersatcore.ac.uk 151 Continuing Education and Life[long] Learning Ideas for BC Landscape Architects provided by British Columbia'snetworkofpost-secondarydigitalrepositories Katherine Dunster brought toyouby CORE 151 Continuing Education and Life[long] Learning Ideas for BC Landscape Architects © 2018 Katherine Dunster Cover: Gill Sans Shadow 100 pt & Sitka 24/18 Body Text: Aboriginal Sans and Gill Sans MT 11/10/9 Secure open access downloads from: https://kora.kpu.ca/islandora/search/Dunster?type=dismax This is an open access work distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 - an Interna- tional Public License that permits non-commercial unrestricted use, sharing, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you may not distribute the modifi ed material. To view a copy of this license, visit: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Quote Sources 1 Julia Child – quoted by Nancy Verde Barr in Backstage with Julia: My Years with Julia Child, (2007, p.246) 2 Eric Hoffer, Refl ections on the Human Condition (1973, Section 32, p.22) 3 John Holt, What Do I Do Monday? (1970, p.22) Notes + Suggestions for Future Editions Send an email (especially if you fi nd a broken link): [email protected] Find something you’re passionate about and keep tremendously interested in it. — Julia Child1 In a time of drastic change it is the learners who inherit the future. The learned usually fi nd themselves equipped to live in a world that no longer exists. -

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada's Military, 1952-1992 by Mallory

War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada’s Military, 19521992 by Mallory Schwartz Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in History Department of History Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Mallory Schwartz, Ottawa, Canada, 2014 ii Abstract War on the Air: CBC-TV and Canada‘s Military, 19521992 Author: Mallory Schwartz Supervisor: Jeffrey A. Keshen From the earliest days of English-language Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television (CBC-TV), the military has been regularly featured on the news, public affairs, documentary, and drama programs. Little has been done to study these programs, despite calls for more research and many decades of work on the methods for the historical analysis of television. In addressing this gap, this thesis explores: how media representations of the military on CBC-TV (commemorative, history, public affairs and news programs) changed over time; what accounted for those changes; what they revealed about CBC-TV; and what they suggested about the way the military and its relationship with CBC-TV evolved. Through a material culture analysis of 245 programs/series about the Canadian military, veterans and defence issues that aired on CBC-TV over a 40-year period, beginning with its establishment in 1952, this thesis argues that the conditions surrounding each production were affected by a variety of factors, namely: (1) technology; (2) foreign broadcasters; (3) foreign sources of news; (4) the influence -

Libraries and Cultural Resources

LIBRARIES AND CULTURAL RESOURCES Archives and Special Collections Suite 520, Taylor Family Digital Library 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, AB, Canada T2N 1N4 www.asc.ucalgary.ca Malcolm Ross fonds. ACU SPC F0027 https://searcharchives.ucalgary.ca/malcolm-ross-fonds An additional finding aid in another format may exist for this fonds or collection. Inquire in Archives and Special Collections. MALCOLM ROSS fonds MsC 18 The Malcolm Ross Fonds MsC 18 CORRESPONDENCE .......................................................................................................................... 2 Correspondence from Canadian writers, and Canadian and American academics .................. 20 CORRESPONDENCE RELATING TO NEW CANADIAN LIBRARY SERIES, MCCLELLAND AND STEWART ....................................................................................................................................................... 24 PUBLISHED WORK BY MALCOLM ROSS ......................................................................................... 50 ABOUT MALCOLM ROSS ................................................................................................................ 50 ABOUT NEW CANADIAN LIBRARY SERIES ...................................................................................... 52 Page 2 MALCOLM ROSS fonds MsC 18 FILE TITLE DATE BOX/FILE Biographical material about M. Ross [197- (?)] 1.1 - typescript (photocopy) and typescript CORRESPONDENCE Academic letters and documents 1934-April 5, 1962 1.2 - arranged chronologically: • E.E. Stoll -

Paperny Films Fonds

Paperny Films fonds Compiled by Melanie Hardbattle and Christopher Hives (2007) Revised by Emma Wendel (2009) Last revised May 2011 University of British Columbia Archives Table of Contents Fonds Description o Title / Dates of Creation / Physical Description o Administrative History o Scope and Content o Notes Series Descriptions o Paperny Film Inc. series o David Paperny series o A Canadian in Korea: A Memoir series o A Flag for Canada series o B.C. Times series o Call Me Average series o Celluloid Dreams series o Chasing the Cure series o Crash Test Mommy (Season I) series o Every Body series o Fallen Hero: The Tommy Prince Story series o Forced March to Freedom series o Indie Truth series o Mordecai: The Life and Times of Mordecai Richler series o Murder in Normandy series o On the Edge: The Life and Times of Nancy Greene series o On Wings and Dreams series o Prairie Fire: The Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 series o Singles series o Spring series o Star Spangled Canadians series o The Boys of Buchenwald series o The Dealmaker: The Life and Times of Jimmy Pattison series o The Life and Times of Henry Morgentaler series o Titans series o To Love, Honour and Obey series o To Russia with Fries series o Transplant Tourism series o Victory 1945 series o Brewery Creek series o Burn Baby Burn series o Crash Test Mommy, Season II-III series o Glutton for Punishment, Season I series o Kink, Season I-V series o Life and Times: The Making of Ivan Reitman series o My Fabulous Gay Wedding (First Comes Love), Season I series o New Classics, Season II-V series o Prisoner 88 series o Road Hockey Rumble, Season I series o The Blonde Mystique series o The Broadcast Tapes of Dr. -

Uncovering the Chains the Black and Aboriginal Slaves Who Helped Build New France

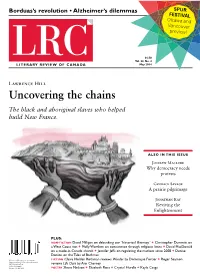

Borduas’s revolution • Alzheimer’s dilemmas SPUR FESTIVAL Ottawa and Vancouver preview! $6.50 Vol. 22, No. 4 May 2014 Lawrence Hill Uncovering the chains The black and aboriginal slaves who helped build New France. ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Jocelyn Maclure Why democracy needs protests Candace Savage A prairie pilgrimage Jonathan Kay Reviving the Enlightenment PLUS: NON-FICTION David Milligan on debunking our “historical illiteracy” + Christopher Dummitt on a West Coast riot + Molly Worthen on coexistence through religious limits + David MacDonald on a made-in-Canada church + Jennifer Jeffs on regulating the markets since 2008 + Denise Donlon on the Tales of Bachman Publications Mail Agreement #40032362 FICTION Claire Holden Rothman reviews Wonder by Dominique Fortier + Roger Seamon Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. reviews Life Class by Ann Charney PO Box 8, Station K Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 POETRY Shane Neilson + Elizabeth Ross + Crystal Hurdle + Kayla Czaga Literary Review of Canada 170 Bloor St West, Suite 710 Toronto ON M5S 1T9 email: [email protected] reviewcanada.ca T: 416-531-1483 • F: 416-531-1612 Charitable number: 848431490RR0001 To donate, visit reviewcanada.ca/support Vol. 22, No. 4 • May 2014 EDITOR Bronwyn Drainie [email protected] CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 2 Outthinking Ourselves 15 May Contain Traces Mark Lovewell, Molly Peacock, Robin A review of Enlightenment 2.0, by Joseph Heath A poem Roger, Anthony Westell Jonathan Kay Kayla Czaga ASSOCIATE EDITOR Judy Stoffman 4 Market Rules 18 Under the Volcano POETRY EDITOR A review of Transnational Financial Regulation A review of Wonder, by Dominique Fortier, Moira MacDougall after the Crisis, edited by Tony Porter translated by Sheila Fischman COPY EDITOR Jennifer Jeffs Claire Holden Rothman Madeline Koch 7 The Memory Thief 19 Making It ONLINE EDITORS Diana Kuprel, Jack Mitchell, A review of The Alzheimer Conundrum: A review of Life Class, by Ann Charney Donald Rickerd, C.M. -

1999 Program – Localities

TWO DAYS OF CANADA 9 99 "Localities" TUESDAY, (EVENING) NOVEMBER 2, 1999 7:30 - 9:30 (Sean O'Sullivan Theatre) Keynote Address: Ann Medina "Moving into a New Neighbourhood: Six Billion and Counting" WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 1999 9:30 -10:30 (Senate Chamber) Opening Remarks Jane Koustas, Director, Centre for Canadian Studies, Brock University lan Angus, Sociology and Anthropology, Simon Fraser University "Place, Locality and Universalization" Chair: Corrado Federici, Department of French, Italian and Spanish, Brock University 10:30 - 11:30 (Senate Chamber) Michael Troughton, Department of Geography, University of Western Ontario "Evaluating the Built Rural Heritage of Southwestern Ontario" Leonard J. Evenden, Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University "Finding Places: Imaginative Re-Construction and Physical Re-Encounter" Chair: Michael Ripmeester, Department of Geography, Brock University 11:30 -12:30 (Senate Chamber) Linda Warley, Department of English, University of Waterloo "Residential Schools and the Dislocations of First Nations Selves" Donna Patrick, Department of Applied Language Studies, Brock University "The Politics of Language in Arctic Quebec: Inuktitut Language Policy and Its Social Effects'' Chair: Bohdan Szuchewycz, Communications, Popular Culture and Film 12:30-1:30 Lunch Break (Lunch available at the University Club, reservations required) 1:30-2:30 (Senate Chamber) Barry Keith Grant, Communications, Popular Culture and Film, Brock University "Local Boy Makes Good or Lost in Space?: The Meaning of Paul Anka" Julie