Stay the Hand of Justice? Evaluating Claims That War Crimes Trials Do More Harm Than Good

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

Self-Defence in the Immediate Aftermath of the Adoption of the UN Charter

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Anticipatory action in self-defence: The law of self-defence - past, presence and future Tibori Szabó, K.J. Publication date 2010 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Tibori Szabó, K. J. (2010). Anticipatory action in self-defence: The law of self-defence - past, presence and future. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 129 7 Self-defence in the immediate aftermath of the adoption of the UN Charter 7.1 Introduction The Charter of the United Nations set up a new world organization with several organs that were given executive, legislative, judicial and other functions. The declared objectives of the new organization were the maintenance of international peace and security, the development of friendly relations and international co-operation in solving international problems, as well as the promotion of human rights and fundamental freedoms.1 These goals were to be achieved through the work of the various organs of the UN, most importantly the Security Council, the General Assembly and the International Court of Justice. -

A State of Play: British Politics on Screen, Stage and Page, from Anthony Trollope To

Fielding, Steven. "The People’s War and After." A State of Play: British Politics on Screen, Stage and Page, from Anthony Trollope to . : Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 83–106. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472545015.ch-003>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 18:24 UTC. Copyright © Steven Fielding 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The People’s War and After Germany invaded Poland on 1st September 1939, forcing a reluctant Neville Chamberlain to declare war two days later. Despite the Prime Minister’s attempt to limit its impact, the conflict set in train transformations that meant Britain would never be the same again. Whether the Second World War was the great discontinuity some historians claim – and the precise extent to which it radicalized the country – remain moot questions, but it undoubtedly changed many people’s lives and made some question how they had been governed before the conflict.1 The war also paved the way for Labour’s 1945 general election victory, one underpinned by the party’s claim that through a welfare state, the nationalization of key industries and extensive government planning it could make Britain a more equal society. The key political moment of the war came in late May and early June 1940 when Allied troops were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk. The fall of France soon followed, meaning Britain stood alone against Hitler’s forces and became vulnerable to invasion for the first time since Napoleon dominated Europe. -

Members of Parliament Disqualified Since 1900 This Document Provides Information About Members of Parliament Who Have Been Disqu

Members of Parliament Disqualified since 1900 This document provides information about Members of Parliament who have been disqualified since 1900. It is impossible to provide an entirely exhaustive list, as in many cases, the disqualification of a Member is not directly recorded in the Journal. For example, in the case of Members being appointed 5 to an office of profit under the Crown, it has only recently become practice to record the appointment of a Member to such an office in the Journal. Prior to this, disqualification can only be inferred from the writ moved for the resulting by-election. It is possible that in some circumstances, an election could have occurred before the writ was moved, in which case there would be no record from which to infer the disqualification, however this is likely to have been a rare occurrence. This list is based on 10 the writs issued following disqualification and the reason given, such as appointments to an office of profit under the Crown; appointments to judicial office; election court rulings and expulsion. Appointment of a Member to an office of profit under the Crown in the Chiltern Hundreds or the Manor of Northstead is a device used to allow Members to resign their seats, as it is not possible to simply resign as a Member of Parliament, once elected. This is by far the most common means of 15 disqualification. There are a number of Members disqualified in the early part of the twentieth century for taking up Ministerial Office. Until the passage of the Re-Election of Ministers Act 1919, Members appointed to Ministerial Offices were disqualified and had to seek re-election. -

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65

Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 To the Chancellors and Vice-Chancellors of the University of Bristol past, present and future Heroic Chancellor: Winston Churchill and the University of Bristol 1929–65 David Cannadine LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © David Cannadine 2016 All rights reserved This text was first published by the University of Bristol in 2015. First published in print by the Institute of Historical Research in 2016. This PDF edition published in 2017. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 18 6 (paperback edition) ISBN 978 1 909646 64 3 (PDF edition) I never had the advantage of a university education. Winston Churchill, speech on accepting an honorary degree at the University of Copenhagen, 10 October 1950 The privilege of a university education is a great one; the more widely it is extended the better for any country. Winston Churchill, Foundation Day Speech, University of London, 18 November 1948 I always enjoy coming to Bristol and performing my part in this ceremony, so dignified and so solemn, and yet so inspiring and reverent. Winston Churchill, Chancellor’s address, University of Bristol, 26 November 1954 Contents Preface ix List of abbreviations xi List of illustrations xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Holocaust Trials and Historical Representation

Donald Bloxham. Genocide on Trial: War Crimes Trials and the Formation of Holocaust History and Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. xix + 273 pp. $149.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-19-820872-3. Reviewed by Michael J. Hoffman Published on H-Holocaust (October, 2003) Holocaust Trials and Historical Representa‐ from a perspective that combined the law and tion media analysis. Douglas focused not only on the We have always known that the historical first Nuremberg trial, but on subsequent media- representation of the Holocaust was profoundly inflected courtroom events such as the Eichmann influenced by the Nuremberg Trials--in particular, trial and the Canadian indictment of Holocaust- the trial of the major Nazi war criminals by the denier Ernst Zundel. Douglas suggests that all International Military Tribunal, whose chief pros‐ Holocaust-related trials have been deeply influ‐ ecutor was Associate Justice Robert Jackson of the enced by Justice Jackson's decision to present to U.S. Supreme Court. Many books have been writ‐ the court vivid footage taken during the liberation ten about the various Nuremberg trials by both of the Western camps of emaciated prisoners, dis‐ journalists (e.g., Robert Persico) and participants membered corpses, crematoria, and ashes. This (Telford Taylor), some of them primarily descrip‐ had the effect, for instance, of suggesting to suc‐ tive, and some more analytic. One of the later tri‐ ceeding generations that the Holocaust took place als, that of the Nazi judges, was fctionalized in primarily in death camps via systematic starva‐ the Stanley Kramer/Abby Mann flm Judgment at tion and execution. -

The Path to Nuremberg and Its Legacy

GRAYA – NO 134 71 The Path to Nuremberg and its Legacy During the Michaelmas Term the Inn held three events: a lecture (the 12th Birkenhead Lecture); a webinar; and a panel discussion – all delivered virtually – to mark the 75th Anniversary of the beginning of the Nuremberg Trials in November 1945. All three drew large audiences from those in this country and across the world. Reflections on the webinar and panel discussion follow. Nuremberg: the background to the trials and the Gray’s Inn participants In a webinar address on 12th November, the Treasurer (Master Stephen Irwin) traced the path to the Nuremberg tribunals held shortly after the end of the Second World War. Their origins, he said, lie in atrocity, a fact of world history ‘at least as old as organised warfare, and its roots lie in the dehumanisation of (its) victims’. This raised questions about whether there existed a duty on all of us to observe a higher law, often described as natural law, to act humanely. Such a law has little truck with pleas that place a premium on blind loyalty to the State or its acts, or indeed on claims ‘I was only following orders’ – the last refuge of many of the rebarbative defendants at Nuremberg. Nor does natural law rest on a belief in God or in any religion, though later in answer to a question from Bishop Michael Doe the Treasurer acknowledged this was not an easy position to adopt. The Treasurer gave a number of illustrations of atrocities in war, stretching from the Roman Empire to the two World Wars, where respect for natural law was absent. -

Landmark Cases in Public International Law

Landmark Cases in Public International Law Edited by Eirik Bjorge and Cameron Miles OXFORD AND PORTLAND, OREGON 2017 Hart Publishing An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Hart Publishing Ltd Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Kemp House 50 Bedford Square Chawley Park London Cumnor Hill WC1B 3DP Oxford OX2 9PH UK UK www.hartpub.co.uk www.bloomsbury.com Published in North America (US and Canada) by Hart Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services 920 NE 58th Avenue, Suite 300 Portland , OR 97213-3786 USA www.isbs.com HART PUBLISHING, the Hart/Stag logo, BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2017 © The editors and contributors severally 2017 The editors and contributors have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as Authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. While every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this work, no responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any statement in it can be accepted by the authors, editors or publishers. All UK Government legislation and other public sector information used in the work is Crown Copyright © . All House of Lords and House of Commons information used in the work is Parliamentary Copyright © . This information is reused under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 ( http://www. -

Filenote Enq 2008/5/2-Pcc

FILENOTE ENQ 2008/5/2-PCC 13 October 2008 ‘Fetters and Roses’ Dinner This was an informal name for a dinner given at the House of Commons on 9 January 1924 for Members of Parliament who had been imprisoned for political or religious reasons. This note is intended to assist identification of as many individuals as possible in a photograph which was donated to the Library, through the Librarian, by Deputy Speaker Mrs Sylvia Heal MP. The original of the photograph will be retained by Parliamentary Archives, while scanned copies are accessible online. A report in The Times the following day [page 12] lists 49 people who had accepted invitations. Some of these were current MPs, while others had been Members in the past and at least two [Mrs Ayrton Gould and Eleanor Rathbone] were to become Members in the future. I have counted 46 people in the photograph, not including the photographer, whose identity is unknown. Mr James Scott Duckers [who never became an MP, but stood as a Parliamentary candidate, against Churchill, in a by- election only a few weeks after the dinner] is described on the photograph as being ‘in the chair’. The Times report also points out that ‘it was explained in an advance circular that the necessary qualification is held by 19 members of the House of Commons, of whom 16 were expected to be present at the dinner’. This raises the question of who the absentees were. One possibility might be George Lansbury [then MP for Poplar, Bow & Bromley], who had been imprisoned twice, in 1913 [after a speech in the Albert Hall appeared to sanction the suffragettes’ arson campaign] and in 1921 [he was one of the Poplar councillors who had refused to collect the rates]. -

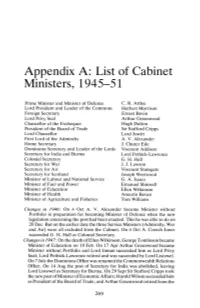

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office. -

Protecting the British War Bride in the United States, 1944–1950

genealogy Article From Good Time Girl to Damsel in Distress: Protecting the British War Bride in the United States, 1944–1950 Gail Savage Department of History, St. Mary’s College of Maryland, St. Mary’s City, MD 20686, USA; [email protected] Received: 27 September 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 30 November 2020 Abstract: During the Second World War, the United Kingdom became an epicenter of transnational, especially transatlantic, marriages, but not all these marriages proved successful. As one disappointed English war bride on her way back home expressed herself, she was “Too shocked to bring her baby up on the black tracks of a West Virginia mining town as against her own home in English countryside of rose-covered fences.” This essay examines the government program developed to provide financial aid and legal advice to British women estranged from or abandoned by their American husbands from the passage of the 1944 Matrimonial Causes (War Marriages) Act to its winding down in 1950. The analysis draws upon a wide range of documents to survey the formulation and implementation of the government response and to consider some illustrative cases dealt with by British consular officials in the United States. These examples illuminate the gap between human behavior envisioned by policy-makers and the more varied behavior encountered by those who carried out the duties charged to them. The cases thus represent the nexus between state intervention and the individual experience of larger-scale social dynamics set off by war and the global movement of populations. Keywords: marriage; divorce; Second World War; social policy; Anglo-American relations 1. -

Law, Politics, and the Attorney- General: the Context and Impact of Gouriet V Union of Post Office Workers

LAW, POLITICS, AND THE ATTORNEY- GENERAL: THE CONTEXT AND IMPACT OF GOURIET V UNION OF POST OFFICE WORKERS PETER RADAN* The role of the Attorney-General as the guardian of the public interest, in considering granting his or her fiat to relator proceedings in relation to the enforcement of public rights, often attracts political controversy. This is vividly illustrated in the circumstances surrounding the decision of the House of Lords in Gouriet v Union of Post Office Workers, which confirmed the traditional rule that the Attorney-General’s decision to refuse to grant his or her fiat is not justiciable (the fiat rule). This article details the rationale for the fiat rule, explores the political context and impact of the Gouriet case, and briefly details the impact of the decision on the rights of a private individual to enforce public rights. I INTRODUCTION It is well established that the Attorney-General, on behalf of the Crown and as the guardian of the public interest, has the principal role in the enforcement of public rights. The traditional rules relating to the standing of a private individual to enforce public rights are encapsulated in the two limbs in Boyce v Paddington Borough Council (Boyce).1 Under the first limb, a private individual can enforce a public right if the infringement of that right also amounts to an infringement of his or her private right.2 Under the second limb, a private individual can enforce a public right if, as a result of an infringement of the public right, he or she would suffer ‘special damage peculiar to himself [or herself]’.3 However, a private individual can also approach the Attorney- General to seek the latter’s fiat or consent to bring relator proceedings.