Patriotic Orations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

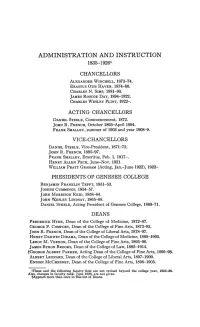

Administration and Instruction 1835-19261

ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION 1835-19261 CHANCELLORS ALEXANDER WINCHELL, 1873-74. ERASTUS OTIS H~VEN, 1874-80. CHARLES N. SIMS, 1881-93. ]AMES RoscoE DAY, 1894-1922. CHARLES WESLEY FLINT, 1922-. ACTING CHANCELLORS DANIEL STEELE, Commencement, 1872. ]OHN R. FRENCH, October 1893-April1894. FRANK SMALLEY, summer of 1903 and year 1908-9. VICE-CHANCELLORS D~NIEL STEELE, Vice-President, 1871-72. ]OHN R. FRENCH, 1895-97. FRANK SMALLEY, Emeritus, Feb. 1, 1917-. HENRY ALLEN PECK, June-Nov. 1921. WILLIAM PR~TT GRAHAM (Acting, Jan.-June 1922), 1922- :PRESIDENTS OF GENESEE COLLEGE BENJAMIN FRANKLIN TEFFT, 1851-53. JosEPH CuMMINGs, 1854-57. JOHN MoRRISON REID, 1858-64. ]OHN WESLEY LINDSAY, 1865-68. DANIEL STEELE, Acting President of Genesee College, 1869-71. DEANS FREDERICK HYDE, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1872-87. GEORGE F. CoMFORT, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1873-93. JOHN R. FRENCH, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1878-97. HE~RY DARWIN DIDAMA, Dean of the College of Medicine, 1888-1905. LEROY M. VERNON, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1893-96. ]AMES BYRON BROOKS, Dean of the College of Law, 1895-1914. tGEORGE ALBERT PARKER, Acting Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1896-98. ALBERT LEONARD, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, 1897-1900. ENSIGN McCHESNEY, Dean of the College of Fine Arts, 1898-1905. IThese and the following faculty lists are not revised beyond the college year, 1925-26. Also, changes in faculty rank, June 1926, are not given. tAppears more than once in this list of Deans. ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION-DEANS Io69 FRANK SMALLEY, Dean of the College of Liberal Arts (Acting, Sept. -

The Book of Discipline

THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH “The Book Editor, the Secretary of the General Conference, the Publisher of The United Methodist Church and the Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision shall be charged with edit- ing the Book of Discipline. The editors, in the exercise of their judgment, shall have the authority to make changes in wording as may be necessary to harmonize legislation without changing its substance. The editors, in consultation with the Judicial Coun- cil, shall also have authority to delete provisions of the Book of Discipline that have been ruled unconstitutional by the Judicial Council.” — Plan of Organization and Rules of Order of the General Confer- ence, 2016 See Judicial Council Decision 96, which declares the Discipline to be a book of law. Errata can be found at Cokesbury.com, word search for Errata. L. Fitzgerald Reist Secretary of the General Conference Brian K. Milford President and Publisher Book Editor of The United Methodist Church Brian O. Sigmon Managing Editor The Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision Naomi G. Bartle, Co-chair Robert Burkhart, Co-chair Maidstone Mulenga, Secretary Melissa Drake Paul Fleck Karen Ristine Dianne Wilkinson Brian Williams Alternates: Susan Hunn Beth Rambikur THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House Nashville, Tennessee Copyright © 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may re- produce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2016. -

FAIRHAVEN HERALD: FAIRHAVEN, WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, MAY 13, 1892 3 STERN FOES of EVIL Bishop Willimnx

FAIRHAVEN HERALD: FAIRHAVEN, WASHINGTON, FRIDAY, MAY 13, 1892 3 STERN FOES OF EVIL Bishop WillimnX. Ninde, of Topeka, was bornin Cortlandville, N, Y., sixty ! completed THE ears ago, and his course at DO YOU READ EIGHTEEN BISHOPS OF THE: %Vesleygn university in 1855, Since " } METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH. { then his ministerial record has been one \ | of comstant progress, and prior to his | } elevation to the Sketches of the Nine Who Have episcopate he gained ; THE Chur‘a; fame, first as a professor and afterward of Affairs in the South and FAIRHAVEN president of | of \Ve-t—Men“ a 8 the Garrett Biblical in- Plety, Learning and Executive! stitute, Ability, ] Bishop Charles Henry Fowler, whose It is something worthy of note in con. episcopal residence is at San Francisco, nection with the history of the Metho l ‘may be numbered among what it is not dist church inAmerica that no breath of improper to term the young leaders of scandal or Methodism. He has yet to see his fifty-Weekly suspicion has ever tainted ! ' the good birthday, and is as active in all | repute of any one of the eight- Aifth World? good J %en living bishops who, personally or works as THE in spirit, take part in this year’s quadren- the most vigor- (Official Paper of County IMPERIAL CITY Whatcom nial conference of the mighty organiza- ous and enthusi- tion which owes its origin to the Wes- astic of his col- leys. Of them it can well be said that leagues. Al they have fought the good fight and kept though a native Conceded to be the | OF the faith. -

J. E. Caldwell &

The L. G. Balfour Co. NEAL F. MEARS, A. M. GENEALOGIST Ma11ujacturers of 1254 North Clark Street, CHICAGO, 10 BADGES MEDALS RINGS CUPS FAVORS TROPHIES PROGRAMS MEDALLIONS Guaranteed Accurate Research STATIONERY PLAQUES Quarterlv Bulletin. National Societv Sons of the American Revolution DOOR PLATES EMBLEM INSIGNIA MEMORIAL TABLETS Our staff and facilities enable us ATHLETIC FIGURES to offer an unusual genealogical serv FRATERNITY JEWELRY ice in all phases. WASHINGTON, D. c., HEADQUARTERS We trace ancestries; prepare appli CONTENTS cation papers for membership in any 1319 F Street N. W., Suite 204 THE PRESIDENT GENERAL'S MESSAGE society; compose charts; compile fam • ily hi tories; and make reports for THE 56TH CONGRESS S. A. R., TRENTON, N. J. STEPHEN 0. FoRO legal-genealogical matters. • Mauager THE BIRm OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS If you have a manuscript or compila • OF COURSE YOU KNOW-OR DO YOU? tion ready to be printed, ask about • our special publishing, sales and dis A MESSAGE FROM THE ORGANIZATION CHAIRMAN tributing service which will aid in re • ducing expen e. A FOUNDER HONORED (David L. Pierson Memorial Cornrniuee) OFFICIAL BADGES OF Two of our publications will be • THEN. S. S. A. R. SERVICE NOTES AND AWARDS ready about ovember l: A HISTORY • OF THE HEVERLY FAMILY, and THE NATIONAL S. A. R. LIBRARY CEREMONIAL BADGE McDONALD AND OTHER BRANCH Donations and Magazines Received ES OF A SOUTHER FAMILY • 14 Karat Gold $33.53 EVENTS OF STATE SOCIETIES Gilded Silver 12.65 TREE. Send for circulars on these • and other works. MINUTES OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE We have a full line of standard ys October 21, 1944 MINIATURE BADGE • tem genealogical charts, blanks, and IN LOVING MEMORY 14 Karat Gold $15.40 accessories. -

The General Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church, From

fi-.-ii&mmwii mmmm 1 3Xmi (L17 Cx.a:<t4tt Biialicol In-diivte itt e^>LC Icvawqe,. 1 The date shows when this volume was taken. To renew this book copy the call No. and give to the hbrarian. HOME USE RULES All Books subject to Recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books for home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. ' Limited books must be re- turned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. OfHcers should arrange for the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out fox a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons. Books of 'spedal value and gift books.^hen the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. !^eaders are asked to re- port all cases of books, marked or mutilated.' Do not deface book! by marks and writiac. — 3 1924 oljn 029 471 1( Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029471103 : THE General Conferences OF THE METHODIST EPISCOPAL CPIURCH FROM 1792 TO 1896. PREPARED BY A LITERARY STAFF UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF REV. LEWIS CURTS, D. D., PUBLISHING AGENT OF THE WESTERN METHODIST BOOK CONCERN. -

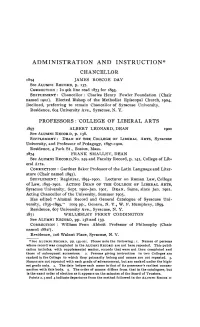

ADMINISTRATION and INSTRUCTION* CHANCELLOR JAMES ROSCOE DAY See AI.UMNI RECORD, P

ADMINISTRATION AND INSTRUCTION* CHANCELLOR JAMES ROSCOE DAY See AI.UMNI RECORD, p. 137. CORRECTION : In 9th line read 1873 for 1893. SUPPI.EMENT: Chancellor: Charles Henry Fowler Foundation (Chair named 1902). Elected Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, 1904. Declined, preferring to remain Chancellor of Syracuse University. Residence, 604 University Ave., Syracuse, N.Y. PROFESSORS: ·cOLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS 1897 ALBERT LEONARD, DEAN 1900 See AI.UMNI RECORD, p. 138. SUPPI.EMENT: DEAN OF THE COI.I.EG:E OF LIBERAl, ARTS, Syracuse University, and Pr-ofessor of Pedagogy, 1897-1900. Residence, 4 Park St., Boston, Mass. 1874 FRANK SMALLEY, DEAN See Ar.UMN1 RECORD,No. 249 and Faculty Record, p. 141, College of Lib eral Arts. CoRRECTION : Gardner Baker Professor of the Latin Language and Liter ature (Chair named 1893). SUPPI.EMENT: Registrar, 1894-1900. Lecturer on Roman Law, College of Law, 1895-1902. ACTING DEAN OF THE Cor.r.EGE OF LIBERAl, ARTS, Syracuse University, Sept. I<JOo-Jan. 1901. DitAN, Same, since Jan. 1901. Acting Chancellor of the University, Summer 1903. Has edited "Alumni Record and General Catalogue of Syracuse Uni versity, 1835-1899," 1009 pp., Geneva, N. Y., W. F. Humphrey, 1899. Residence, 6o7 University Ave., Syracuse, N. Y. 1871 WELLESLEY PERRY CODDINGTON See AI.UMNI RECORD, pp. 138 and I 39· CoRRECTION : William Penn Abbott Professor of Philosophy (Chair named 1882?). Resirlence, 106 Walnut Place, Syracuse, N.Y. *See ALUMNI RECOilD, pp. 135- 21I. Please note the following: r. Names of persons whose record was completed in the ALUMNI RECOilD are not here repeated. This publi cation includes, with supplemental matter, records that were not then completed and those of subsequent accessions. -

Rowe: Trans-Atlantic Social Gospel, P. 1 Ninth Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies Somerville College, Oxford July

Rowe: Trans-Atlantic Social Gospel, p. 1 Ninth Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies Somerville College, Oxford July 28-August 7, 1992 DRAFT COPY: Not for circulation beyond Working Group 3 Post-Wesley History TRANS-ATLANTIC SOCIAL GOSPEL: BRITISH INFLUENCES ON AMERICAN METHODIST SOCIAL THOUGHT AND PRACTICE 1890-1910 Kenneth E. Rowe Drew University Theological School Madison, New Jersey USA One manifestation of the maturity of American religious history in our time is a substantial corpus of literature on the social gospel. From Visser 't Hooft's 1928 study, The Background of the Social Gospel in America 1 through Howard Hopkins' classic 1940 study The Rise of the Social Gospel in American Protestantism2 to Don Gorrell 's 1988 study The Age of 3 Social Responsibility , the works in question vary in aim and emphasis but share a common premise: the social gospel was a unique and mainly indigenous American religious movement. The notion of the Americanness of the Social Gospel has never been accompanied by any but the most casual s~pporting arguments and calls for comparative studies to test the assumption. William R. Hutchinson of Harvard questioned the 1 W. A. visser 't Hooft, The Background of the Social Gospel in America. Haarlem: H. D. Tjenk Willink & Zoon, 1928. 2 Charles Howard Hopkins, The Rise of the Social Gospel in American Protestantism, 1865-1915. New Haven : Yale University Press, 1940. 3 Dional K. Gorrell, The Age of Social Responsibility: The Social Gospel in the Progressive Era 1900-1920. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1988. 1 Rowe: Trans-Atlantic Social Gospel, p. -

United Methodist Bishops Ordination Chain 1784 - 2012

United Methodist Bishops Ordination Chain 1784 - 2012 General Commission on Archives and History Madison, New Jersey 2012 UNITED METHODIST BISHOPS in order of Election This is a list of all the persons who have been consecrated to the office of bishop in The United Methodist Church and its predecessor bodies (Methodist Episcopal Church; Methodist Protestant Church; Methodist Episcopal Church, South; Church of the United Brethren in Christ; Evangelical Association; United Evangelical Church; Evangelical Church; The Methodist Church; Evangelical United Brethren Church, and The United Methodist Church). The list is arranged by date of election. The first column gives the date of election; the second column gives the name of the bishop. The third column gives the name of the person or organization who ordained the bishop. The list, therefore, enables clergy to trace the episcopal chain of ordination back to Wesley, Asbury, or another person or church body. We regret that presently there are a few gaps in the ordination information, especially for United Methodist Central Conferences. However, the missing information will be provided as soon as it is available. This list was compiled by C. Faith Richardson and Robert D. Simpson . Date Elected Name Ordained Elder by 1784 Thomas Coke Church of England 1784 Francis Asbury Coke 1800 Richard Whatcoat Wesley 1800 Philip William Otterbein Reformed Church 1800 Martin Boehm Mennonite Society 1807 Jacob Albright Evangelical Association 1808 William M'Kendree Asbury 1813 Christian Newcomer Otterbein 1816 Enoch George Asbury 1816 Robert Richford Roberts Asbury 1817 Andrew Zeller Newcomer 1821 Joseph Hoffman Otterbein 1824 Joshua Soule Whatcoat 1824 Elijah Hedding Asbury 1825 Henry Kumler, Sr. -

THE BOOK of DISCIPLINE of the UNITED METHODIST CHURCH CONS001936QK001.Qxp:QK001.Qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page Ii

CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page i THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page ii “The Book Editor, the Secretary of the General Conference, the Pub- lisher of The United Methodist Church, and the Committee on Corre- lation and Editorial Revision shall be charged with editing the Book of Discipline. The editors, in the exercise of their judgment, shall have the authority to make changes in wording as may be necessary to harmonize legislation without changing its substance. The editors, in consultation with the Judicial Council, shall also have authority to delete provisions of the Book of Discipline that have been ruled uncon- stitutional by the Judicial Council.” —Plan of Organization and Rules of Order of the General Confer- ence, 2008 See Judicial Council Decision 96, which declares the Discipline to be a book of law. Errata can be found at Cokesbury.com, word search for Errata. L. Fitzgerald Reist Secretary of the General Conference Neil M. Alexander Publisher and Book Editor of The United Methodist Church Judith E. Smith Executive Editor Marvin W. Cropsey Managing Editor The Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision Eradio Valverde, Chairperson Richard L. Evans, Vice Chairperson Annie Cato Haigler, Secretary Naomi G. Bartle CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page iii THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2008 The United Methodist Publishing House Nashville, Tennessee CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page iv Copyright © 2008 The United Methodist Publishing House. -

METHODIST BISHOPS THEIR ORDINATION AS DEACONS and ELDERS by Roy H

METHODIST BISHOPS THEIR ORDINATION AS DEACONS AND ELDERS By Roy H. Short (We are indebted to Bishop Roy H. Short, Secretary of the Coun- cil of Bishops, for a long and arduous piece of historical research in which he has traced the ordination of the bishops of Methodism. Starting with Bishop Thomas Coke, Bishop Short has supplied the facts concerning the ordination as deacon and elder for the episcopal leaders of the church. In the tabular compilation below, Bishop Short gives the year of each man's elevation to the episcopacy, his name, date of birth, date of death (if he has passed on), and the name of the bishop or bishops who ordained him deacon and elder. The dates of the ordinations are not given. The table lists all of the bishops of the church from 1784 to 1967. The bishops elected by The United Methodist Church in 1968 and those from the former Evangelical United Brethren Church who became bishops in the united church in 1968 are not included. In sending the results of his research to Methodist History, Bishop Short said that it was "a long but interesting task." It will be noted that he has supplied full information concerning all but fifteen of the bishops. He and this magazine will be grateful to anyone who can furnish the missing data on Bishops Bashford, Birney, Chen, Dodge, Elphick, M. S. Hughes, W. A. C.' Hughes, Hartzell, Kim, Lowe, D. H. Moore, Nuelsen, Oldham, J. W. Roberts, and Wang. Communications to Bishop Short may be addressed to him in care of Methodist History, Lake Junaluska, N. -

Books On-Line: Complete List by Title

Books On-line: Complete List by Title COMPLETE LIST BY TITLE List too long? See the main on-line books page to browse it in segments, or search for particular books. Please suggest any additions to [email protected]. Additional titles not locally indexed can be found at the other repositories listed on the main on-line books page. See also listings by author. ● "...For the Hour of His Judgment Is Come..." by Annikki Matthan (HTML in Finland) ● The "B. O. W. C.": A Book for Boys (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1869) by James De Mille (page images at canadiana.org) ● The "Bab" Ballads by William S. Gilbert (Gutenberg text) ● "Both Sides Told," or, Southern California As It Is by Mary C. Vail (HTML at LOC) ● "Bringing the Ranks Up to the Standard" by Emma L. Burnett (page images at canadiana.org) ● "Cato" on Constitutional "Money" and Legal Tender (Charleston: Evans & Cogswell, 1862) by Thomas Jefferson Withers (HTML and TEI at UNC) ● "Dot It Down": a Story of Life in the North-West (Toronto : Hunter, Rose, 1871) by Alexander Begg (page images at canadiana.org) ● "Esmeralda" Waltz-Lanciers by William W. Florence (HTML and page images at LOC) ● "Greenbacks" by Observer (page images at MOA) ● "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder by Vladimir Ilich Lenin, trans. by Julius Katzer (HTML at marxists.org) ● "Little Sheaves" Gathered While Gleaning After Reapers by Caroline M. Nichols Churchill (HTML at LOC) ● "Mademoiselle Miss": Letters from an American Girl Serving with the Rank of Lieutenant in a French Army Hospital at the Front -

THE BOOK of DISCIPLINE of the UNITED METHODIST CHURCH CONS001936QK001.Qxp:QK001.Qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page Ii

CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page i THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page ii “The Book Editor, the Secretary of the General Conference, the Pub- lisher of The United Methodist Church, and the Committee on Corre- lation and Editorial Revision shall be charged with editing the Book of Discipline. The editors, in the exercise of their judgment, shall have the authority to make changes in wording as may be necessary to harmonize legislation without changing its substance. The editors, in consultation with the Judicial Council, shall also have authority to delete provisions of the Book of Discipline that have been ruled uncon- stitutional by the Judicial Council.” —Plan of Organization and Rules of Order of the General Confer- ence, 2008 See Judicial Council Decision 96, which declares the Discipline to be a book of law. Errata can be found at Cokesbury.com, word search for Errata. L. Fitzgerald Reist Secretary of the General Conference Neil M. Alexander Publisher and Book Editor of The United Methodist Church Judith E. Smith Executive Editor Marvin W. Cropsey Managing Editor The Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision Eradio Valverde, Chairperson Richard L. Evans, Vice Chairperson Annie Cato Haigler, Secretary Naomi G. Bartle CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page iii THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2008 The United Methodist Publishing House Nashville, Tennessee CONS001936QK001.qxp:QK001.qxd 11/10/08 8:05 AM Page iv Copyright © 2008 The United Methodist Publishing House.