Francis Asbury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1855 Church Link with Early Ingersoll

.... / ' ■ I EARLY CHURCHES \ , A InGKRSOLL AAD VICINITY PRESBYTERIAN The Erskine Presbyterian congregation was organized in 1852. It was known as a United Presbyterian church often called the UPs. ‘A church of brick construction was erected on the north west corner of Charles St. and Boles St. in 1855* It was a very prominent church in its early years. Thomas Hyslop of Nest Oxford was*one of the elders and sessions clerk as well as precentor for 15 years. Hr. Hyslop was a rural neighbor of B.C. J. Ne*were well acquainted. Hi-h above*the front door of the church in the apex was a circle of wood bearing the inscription "Erskine Presbyterian Church." The congregation of this church joined the Knox church in 188°. The building was used by Nagle and Hills, contractors for a number of yea s. The sash and door factory was in the upper portion, which was the auditorium, and the heavy machinery was on the ground floor. I have be^n in the building many time. The building was demolished in 1950 and a more suitable^buildin^ erected by the Beaver Lumber Co, A’ Knox Presbyterian church, a Free church, also called the Kirk, began worship in a grove of trees i n l E ^ and in .,18^-7 erected, a brick, church on the same site. This church was located on the north side of St. Andrews street and east of Thames Street. The rear of the property extended to the north to a line which later (1881) was C.P.R. -

Village in the City Historic Markers Lead You To: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail – a Pre-Civil War Country Estate

On this self-guided walking tour of Mount Pleasant, Village in the City historic markers lead you to: MOUNT PLEASANT HERITAGE TRAIL – A pre-Civil War country estate. – Homes of musicians Jimmy Dean, Bo Diddley and Charlie Waller. – Senators pitcher Walter Johnson's elegant apartment house. – The church where civil rights activist H. Rap Brown spoke in 1967. – Mount Pleasant's first bodega. – Graceful mansions. – The first African American church on 16th Street. – The path President Teddy Roosevelt took to skinny-dip in Rock Creek Park. Originally a bucolic country village, Mount Pleasant has been a fashion- able streetcar suburb, working-class and immigrant neighborhood, Latino barrio, and hub of arts and activism. Follow this trail to discover the traces left by each succeeding generation and how they add up to an urban place that still feels like a village. Welcome. Visitors to Washington, DC flock to the National Mall, where grand monuments symbolize the nation’s highest ideals. This self-guided walking tour is the seventh in a series that invites you to discover what lies beyond the monuments: Washington’s historic neighborhoods. Founded just after the Civil War, bucolic Mount Pleasant village was home to some of the city’s movers and shakers. Then, as the city grew around it, the village evolved by turn into a fashionable streetcar suburb, a working-class neigh- borhood, a haven for immigrants fleeing political turmoil, a sometimes gritty inner-city area, and the heart of DC’s Latino community. This guide, summariz- ing the 17 signs of Village in the City: Mount Pleasant Heritage Trail, leads you to the sites where history lives. -

The Stanton-Ames Order and Union Military-Supported Church Confiscation During the American Civil War

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2021 We May Undertake to Run the Churches: The Stanton-Ames Order and Union Military-Supported Church Confiscation During the American Civil War Todd Ernest Sisson Missouri State University, [email protected] As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the History of Religion Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Sisson, Todd Ernest, "We May Undertake to Run the Churches: The Stanton-Ames Order and Union Military-Supported Church Confiscation During the American Civil arW " (2021). MSU Graduate Theses. 3619. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3619 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WE MAY UNDERTAKE TO RUN THE CHURCHES: THE STANTON-AMES ORDER AND UNION MILITARY-SUPPORTED -

Freeborn Garrettson and African Methodism

Methodist History, 37: 1 (October 1998) BLACK AND WHITE AND GRAY ALL OVER: FREEBORN GARRETTSON AND AFRICAN METHODISM IAN B. STRAKER Historians, in describing the separation of Africans from the Methodist Episcopal Church at the tum of the 19th century, have defined that separation by the possible reasons for its occurrence rather than the context within which it occurred.' Although all historians acknowledge, to some degree, that racial discrimination led to separate houses of worship for congregants of African descent, few have probed the ambivalence of that separation as a source of perspective on both its cause and degree; few have both blamed and credited the stolid ambiguity of Methodist racial interaction for that separation. Instead, some historians have emphasized African nationalism as a rea son for the departure of Africans from the Methodist Episcopal Church, cit ing the human dignity and self-respect Africans saw in the autonomy of sep arate denominations. Indeed, faced with segregated seating policies and with the denial of both conference voting rights and full ordination, Africans struck out on their own to prove that they were as capable as whites of fully con ducting their own religious lives. Other historians have placed the cause for the separation within the more benign realm of misunderstandings by the Africans about denominational polity, especially concerning the rights of local congregations to own and control church property. The accuracy of each point of view notwithstanding, black hnd white racial interaction in early Methodism is the defining context with which those points of view must be reconciled. Surely, a strident nationalism on the part of Africans would have required a renunciation, or even denunciation, of white Methodists and "their" church, which is simply not evident in the sources. -

NOTES and DOCUMENTS the African Methodists of Philadelphia

NOTES AND DOCUMENTS The African Methodists of Philadelphia, 1794-1802 The story of the exodus of the black Methodists from St. George's Church in Philadelphia in the late eighteenth century and the subse- quent founding of Bethel African Methodist Church was first told by Richard Allen in a memoir written late in his life.1 Allen's story, fa- mous as a symbol of black independence in the Revolutionary era, il- lustrates the extent to which interracial dynamics characterized social life and popular religion in post-Revolutionary Philadelphia. The birth of Allen's congregation in the city was not an accident: Philadelphia's free black population had grown rapidly with the migration of ex-slaves attracted by Pennsylvania's anti-slavery laws and jobs afforded by the city's expanding commercial economy. The founding of the church also highlights the malleable character of American religion at this time; the ways religious groups became rallying points for the disenfranchised, the poor, and the upwardly mobile; and the speed and confidence with which Americans created and re-created ecclesiastical structures and enterprises. Despite the significance of this early black church, historians have not known the identities of the many black Philadelphians who became Methodists in the late eighteenth century, either those joining Allen's *I want to thank Richard Dunn, Gary Nash, and Jean Soderlund for their thoughtful comments, and Brian McCloskey, St. George's United Methodist Church, Philadelphia 1 Richard Allen, The Life Experience and Gospel Labours of the Rt. Rev Rtchard Allen (Reprint edition, Nashville, TN, 1960) My description of the black community in late eighteenth-century Philadelphia is based on Gary B Nash, "Forging Freedom The Eman- cipation Experience in the Northern Seaport Cities, 1775-1820" in Ira Berlin and Ronald Hoffman, eds., Slavery and Freedom tn the Age of the American Revolution, Perspectives on the American Revolution (Charlottesville, VA, 1983), 3-48. -

2016 General Conference Preview

APRIL 2016 • VOL. 20 NO. 10 FEATURED: 2016 General Conference Preview PAGES 6-13 INSIDE THIS ISSUE News from the Episcopal Office 1 Events & Announcements 2 Christian Conversations 3 Local Church News 4-5 General Conference 6-13 Historical Messenger 14-15 Conference News 16-17 ON THE 16 COVER Montage picturing delegates at round tables at the 2012 General Conference and Peoria Convention-site of the 2016 General Conference The Current (USPS 014-964) is published Send materials to: monthly by the Illinois Great Rivers P.O. Box 19207, Springfield, IL 62794-9207 Conference of The UMC, 5900 South or tel. 217.529.2040 or fax 217.529.4155 Second Street, Springfield, IL 62711 [email protected], website www.igrc.org An individual subscription is $15 per year. Periodical postage paid at Peoria, IL, and The opinions expressed in viewpoints are additional mailing offices. those of the writers and do not necessarily POSTMASTER: Please send address reflect the views of The Current, The IGRC, changes to or The UMC. The Current, Illinois Great Rivers Communications Team leader: Paul E. Conference, Black Team members: Kim Halusan and P.O. Box 19207, Springfield, IL 62794-9207 Michele Willson 13 IGRC’s best kept secret: Your church has FREE Current subscriptions! Due to the faithful payment of apportionments of our churches, free subscriptions to The Current are available to each IGRC congregation. The bad news? One-half of those subscriptions go unclaimed! Pastors: Check the list of subscribers to The Current for your church by visiting www.igrc.org/subscriptions. Select the District, Church and enter the church’s six-digit GCFA number. -

Bishop Matthews Hosts Pan Methodist Gathering

Volume 6 Number 4 May 2005 Bishop Matthews hosts Pan Methodist gathering Bishop Marcus Matthews con- vened a gathering of the Pan Methodist Bishops from the Phila- delphia area Tuesday, April 5th. Discussion focused on how the “Because of “Methodist Family” can collabo- Winn Dixie” rate to raise the visibility and witness of Methodists in the movie review Philadelphia area. Further discus- Page 3 sion included partnering with denominational seminaries to set- up satellite campuses in Philadel- phia, exploring ways to stabilize church communities, challenging federal and state leaders and legis- Connection lators to vote against the pro- giving insert posed Medicaid cuts, sponsoring Page 5 annual Pan Methodist seminars and worship services with the Bishops preaching. A long range planning commit- tee will be established to develop further plans and events includ- ing contacting other Bishops in Those in attendance included (left to right) Presiding Elder John Gee representing Bishop Charles L. Helton, 7th District of the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, Bishop Richard F. Norris, Sr., First Annual Conference the Pan Methodist Family. District of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, Bishop Marcus Matthews, and Rev. Ralph E. Blanks, Central District Superintendent Designee representing the Cabinet of the Eastern Pennsylvania supplement Conference. Page AC-1 Gala to Bringing shalom to communities around celebrate old INDEX Delaware CALENDAR............ 2 the globe APPOINTMENTS.... 3 Conference THE NATION ......... 4 By Suzy Keenan Rev. Dr. Patricia Bryant Harris THE WORLD ......... 13 In the Eastern Pennsylvania The Delaware Conference — CLASSIFIEDS ........ 16 Conference, four communities a source of pride, an era of have chosen to create “Shalom shame. -

August 2014 Issue.Indd

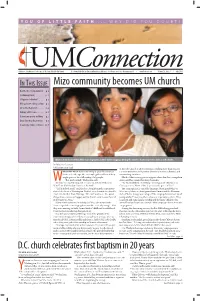

YOU OF LITTLE FAITH ... WHY DID YOU DOUBT? Baltimore-Washington Conference of The United Methodist Church • BecomingConnection fully alive in Christ and making a diff erence in a diverse and ever-changing world • www.bwcumc.org • Volume 25, Issue 7 • July 2014 UM IN THIS ISSUE Mizo community becomes UM church The Word is ‘Independence’ p. Conference Events ................ p. UM pastor ‘refrocked’............ p. Bishop issues rulings of law p. Art and the Holy in D.C.............. p. Making a Diff erence............ p. Downtown prayer walking p. Grays becomes deaconness p. Strawbridge Shrine celebrates p. Melissa Lauber Children from the new Mizo UMC choir sing hymns in their native language during the church’s chartering service June in Rockville. By Melissa Lauber UMConnection Staff of how the church is alive in mission, sending more than $12,000 hen they first started meeting at Zuali Malsawma’s a year to ministries in Myanmar (formerly known as Burma) and house a decade ago, the 10 people gathered hoped they surrounding countries. might grow to be a fellowship of 25 people. Much of that money goes to support other churches’ evangelism “But God worked,” Malsawma said. eff orts and has resulted in many baptisms. WOn June 22, exactly 179 people became members of the new “We thank God for everything,” Chhunga said. “God uses us. Mizo United Methodist Church in Rockville. God inspires us. Above all we depend on the grace of God.” “God is indeed good,” said the Rev. Joseph Daniels, superinten- Th e congregation is united by language. Most speak Mizo or dent of the Greater Washington District, as he handed the church’s Mizo tawng. -

Remembering Francis Asbury Erik Alsgaard the Rev

FOR IN GOD ALL THINGS WERE CREATED: ALL THINGS HAVE BEEN CREATED THROUGH GOD AND FOR GOD. – COLOSSIANS 1:16 Baltimore-Washington UM Conference of The United Methodist Church • BecomingConnection fully alive in Christ and making a difference in a diverse and ever-changing world • www.bwcumc.org • Volume 27, Issue 04 • April 2016 Remembering Francis Asbury Erik Alsgaard The Rev. Emora Brannan speaks at the dedication of a new monument (tallest one, to his right) honoring Bishop Francis Asbury and others at Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Baltimore. On the platform are the Rev. Travis Knoll, left, pastor of Lovely Lane UMC, and Walter Tegeler, owner of the company that made the monument. By Erik Alsgaard Asbury knew popular American culture long before UMConnection Staff anyone else because of his extensive travels, Day said. His mission was to make the Gospel relevant to BMCR meets in ishop Francis Asbury was remembered as the everyone he met. One piece of American culture he “The Prophet of the Long Road” on the 200th abhorred was slavery; Asbury called it a “moral evil.” Baltimore anniversary of his death during worship at And yet, Asbury made accommodations for slave- Lovely Lane UMC and ceremonies at Mt. Olivet holding Methodists, mostly in the South, in order to By Melissa Lauber & Larry Hygh* BCemetery, both in Baltimore, on April 3. hold the church together, Day said. “This haunted him UMConnection Staff Asbury, an icon of Methodism from its start in the rest of his life.” Colonial America, arrived on these shores from England At the Christmas Conference of 1784, held in tanding before the 330 members of the in 1771 at the age of 26. -

History of the Rayto Methodist Church Rayto , Georgia by Miss Christine Davidson Brown, Sharon

HISTORY OF THE RAYTO METHODIST CHURCH RAYTO , GEORGIA BY MISS CHRISTINE DAVIDSON BROWN, SHARON , RAYTOWN METHODIST CHURCH The loss of the original recorda of the Raytown Methodist Church, Taliaferro County, Georgia, presumed to have been destroyed by fire in the home of the late Samuel J. Flynt, long a Steward and Superin tendent of the Sunday School, renders impossible the compilation of a full and detailed account of its early and intensely interesting his tory. All the more important, therefore, is the obligation of the pres ent to preserve its records for the future. From the traditions handed down to us by the oldest members of the com munity, we learn that Raytown, or "Ray's Place lt as it was called, then in Wilkes County, was named for a Ray family from New York and living at that time in Washington. So far as is known this family was in no way related to the Barnett - Ray family so prominently identified with the history of Raytown in more receJ;lt years. "Ray's Place lt was the designation given to the recreation center established on Little River where racing, gambling, cock-fighting, drinking, and other favorite pastimes of the livelier social set of near-by Washington could be enjoyed without any, to them, undue and undesired restraint. As is often the history of such places, ItRay's Place lt had its day, its popularity declined, and for what reason we do not know, nor care, the Ray family returned to New York. EVen here we mourn the loss of our early church recordst Truly, it would prove most pertinent to our purpose if further research into the still intact records of old Wilkes should show that the decline and fall of "Ray's Place lt were marked by the coming of Methodism. -

Holston Methodism

HOLSTON METHODISM REV. THOMAS STRINGFIELD. HOLSTON METHODISM FROM ITS ORIGIN TO THE PRESENT TIME. By R. N. PRICE. VOLUME III. From the Year 1824 to the Year 1844. Nashville, Tenn.; Dallas, Tex.: Publishing House of the M. E. Church, South. Smith & Lamar, Agents. 1908. Entered, according to Aet of Congress, in the year 190S, By R. N. Pkice, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. PREFACE. The tardiness with which the successive volumes of this work have been issued has evidently abated somewhat the interest of preachers and people in it; but this tardiness has grown out of circumstances which I have not been able to control. There is more official matter in this volume than in its predecessors, making it a little less racy than the oth- ers; but the official matter used is of considerable historic value. Thus while the volume is heavier than the others as to entertaining qualities, it is also heavier as to historic importance. The chapters on Stringfield, Fulton, Patton, Sevier, Brownlow, and the General Conference of 1844 are chapters of general interest and thrilling import, not on ac- count of ability in the writing, but on account of the in- trinsic value of the matter recorded. I owe my Church an explanation for dwelling so much at length upon the life of Senator Brownlow. It is my busi- ness to record history, not to invent it. A Methodist preach- er who lived as long as Brownlow did, was constantly be- fore the public, took an active part in theological and eccle- siastical controversies, was so gifted and was such a pro- digious laborer, must necessarily have made much history, which could not be ignored by an honest historian. -

CHAPTER I CRUSADING in the SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS To

CHAPTER I CRUSADING IN THE SOUTHERN HIGHLANDS To ADMIT that one sprang from the second families of Virginia marks a strange trait. Indeed, it may well be argued that if the admission were publicly made and without provocation, it points to positive idiosyncrasies. So much undoubtedly can be proved on William Gannaway Brownlow, known to his time and to history as the Fighting Parson. Like Abraham Lincoln, his ancestry was the short and simple annals of the poor, but un like Lincoln he made a virtue out of telling it. Brownlow's father was Joseph A. Brownlow, who was born in Rockbridge County, Virginia in 1781. He spent his life drift ing down the great valleys of Southern Appalachia, and by 1816, when he died, he had reached East Tennessee. Brownlow's mother was Catherine Gannaway, also a Virginian. This couple had proceeded southwestward as far as a farm in Wythe County, when their first child was born. Itwas on the ~9th day of August, 1805, and the child was a boy. They named him William, to do honor to one of his father's brothers, and they added Gannaway out of respect for his mother's family. Two brothers and two sisters followed in rather close succession, to be his playmates. At the age of thirty-five his father died, a victim of the hard life of the frontiersman, and his mother, with feelings too tender for so dire a fate, grieved much for her departed husband, and followed him within less than three months. At the age of eleven Andrew Johnson, later to loom large on the Brownlow horizon, had lost only his father; Brownlow at the same age had lost both father and mother.