Lepea: That Model Village in Samoa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Public Administration Sector Plan for Samoa, 2007 - 2011

© Government of Samoa 2006 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1998, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the Government of Samoa. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: The Chief Executive Officer, Office of the Public Service Commission P.O. Box 73 Apia Samoa or by fax: 685 24215, Tel: 685 22123, email: [email protected] i ii Abbreviations ACEO Assistant Chief Executive Officer AG Office of the Attorney General AU Audit Office CDC Cabinet Development Committee CEO Chief Executive Officer PBs Public Bodies GoS Government of Samoa HRMIS Human Resource Management Information System IAD Internal Affairs Division LA Legislative Assembly Department M&E Monitoring & Evaluation MCIL Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Labour MJCA Ministry of Justice and Court Administration MOF Ministry of Finance MPMC Ministry of the Prime Minister and Cabinet MWCSD Ministry of Women, Community and Social Development NPM New Public Management OB Ombudsman Office PDC Professional Development Centre PMS Performance Management System PSC Office of the Public Service Commission PSIF Public Sector Improvement Facility PAS Public Administration Sector PASP Public Administration Sector Plan PIMU Policy Implementation and Monitoring Unit SDS Strategy for the Development of Samoa SOEMD State Owned Enterprises Monitoring Division STA Short Term Adviser TOR Term of Reference WTO World Trade Organisation iii Table of Content Foreword ……………..………………………………………………………………….i Word from the Steering Committee …………………………………………………..ii Abbreviations ……..…………………………………………………………………….ii Table of Content …..………………………………………………………...……........iii Introduction ……..……………………………………………………………………..1 Structure of the Plan …………………………………………………………………...2 Part 1.Framework of the Plan ...……………………………………………………….3 1.1. Principles Underlying the Plan …..………………………………………...4 1.2. -

Conflicting Power Paradigms in Samoa's

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. CONFLICTING POWER PARADIGMS IN SAMOA’S “TRADITIONAL DEMOCRACY” FROM TENSION TO A PROCESS OF HARMONISATION? A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science at Massey University, Albany, New Zealand Christina La’alaai-Tausa 2020 COPYRIGHT Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. 2 ABSTRACT This research argues that the tension evident between western democracy and Samoa’s traditional leadership of Fa’amatai has led to a power struggle due to the inability of the government to offer thorough civic education through dialectical exchange, proper consultation, discussion and information sharing with village council leaders and their members. It also argues that Fa’amatai are being disadvantaged as the government and the democratic system is able to manipulate cultural practices and protocols to suit their political needs, whereas village councils are not recognized or acknowledged by the democratic system (particularly the courts), despite cultural guidelines and village laws providing stability for communities and the country. In addition, it claims that, despite western academics’ arguments that Samoa’s traditional system is a barrier to a fully-fledged democracy, Samoa’s Fa’amatai in theory and practice in fact proves to be more democratic than the democratic status quo. -

Faleata East - Upolu

Community Integrated Management Plan Faleata East - Upolu Implementation Guidelines 2018 COMMUNITY INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT PLAN IMPLEMENTATION GUIDELINES Foreword It is with great pleasure that I present the new Community Integrated Management (CIM) Plans, formerly known as Coastal Infrastructure Management (CIM) Plans. The revised CIM Plans recognizes the change in approach since the first set of fifteen CIM Plans were developed from 2002-2003 under the World Bank funded Infrastructure Asset Management Project (IAMP) , and from 2004-2007 for the remaining 26 districts, under the Samoa Infrastructure Asset Management (SIAM) Project. With a broader geographic scope well beyond the coastal environment, the revised CIM Plans now cover all areas from the ridge-to-reef, and includes the thematic areas of not only infrastructure, but also the environment and biological resources, as well as livelihood sources and governance. The CIM Strategy, from which the CIM Plans were derived from, was revised in August 2015 to reflect the new expanded approach and it emphasizes the whole of government approach for planning and implementation, taking into consideration an integrated ecosystem based adaptation approach and the ridge to reef concept. The timeframe for implementation and review has also expanded from five years to ten years as most of the solutions proposed in the CIM Plan may take several years to realize. The CIM Plans is envisaged as the blueprint for climate change interventions across all development sectors – reflecting the programmatic approach to climate resilience adaptation taken by the Government of Samoa. The proposed interventions outlined in the CIM Plans are also linked to the Strategy for the Development of Samoa 2016/17 – 2019/20 and the relevant ministry sector plans. -

Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port: Due

Due Diligence Report Project Number: 47358-002 May 2019 SAM: Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port Project (Grant xxxx) Prepared by the Samoa Ports Authority for the Asian Development Bank. This due diligence report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgements as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Enhancing Safety, Security and Sustainability of Apia Port – Social and Poverty Assessment Report CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 4 April 2016) Tala – Samoan Tala (SAT) = $1.00 = ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AUA - Apia Urban Area DDR - Due Diligence Report EA - Executing Agency EMP - Environmental Management Plan EPA - Environmental Protection Agency GOS - Government of the Samoa GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism HIES - Household Income and Expenditures Survey IA - Implementing Agency IP - Indigenous People IR - Involuntary Resettlement MNRE - Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment MOF - Ministry of Finance MOR - Ministry of Revenue PIC - Pacific Island Countries PUMA - Planning and Urban Management Authority RP - Resettlement Plan SPA - Samoa Ports Authority -

51268-001: Central Cross Island Road Upgrading Project

DRAFT Resettlement Plan March 2020 SAM: Central Cross Island Road Upgrading Project (CCIRUP) Prepared by the Land Transport Authority of Samoa for the Asian Development Bank. i CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 02 September 2019) Currency unit – Samoan Tala (WST) WST1.00 = $ 0.37 $1.00 = WST 2.69 ABBREVIATIONS AP – affected persons AoG – Assemblies of God CCCS – Congregational Church of Samoa CCIR – Central Cross Island Road CCIRUP – Central Cross Island Road Upgrading Project (the Project) COEP – codes of environmental practice ERAP – Enhanced Road Access Project ESIA – environmental and social impact assessment GCLS - Grievance Complaint Logging System LDS – Latter Day Saints LTA – Land Transport Authority MNRE – Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment MOF – Ministry of Finance MWCSD – Ministry of Women, Community and Social Development OHS – occupational health and safety PMU – project management unit PUMA – Planning and Urban Management Division of MWTI RC – roman catholic RP – resettlement plan TCE – Tropical Cyclone Evan WST – Samoan Tala WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km (kilometer) – length relevant to road m (meter) – Length or width relevant to road vpd (vehicles per day) – traffic volume NOTES In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the Asian Development Bank (ADB)'s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of the ADB website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Vailima Letters

Vailima Letters Robert Louis Stevenson Project Gutenberg's Etext of Vailima Letters, by R. L. Stevenson #15 in our series by Robert Louis Stevenson Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. Vailima Letters by Robert Louis Stevenson January, 1996 [Etext #387] Project Gutenberg's Etext of Vailima Letters, by R. L. Stevenson *****This file should be named valma10.txt or valma10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, valma11.txt. VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, valma10a.txt. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, for time for better editing. Please note: neither this list nor its contents are final till midnight of the last day of the month of any such announcement. The official release date of all Project Gutenberg Etexts is at Midnight, Central Time, of the last day of the stated month. A preliminary version may often be posted for suggestion, comment and editing by those who wish to do so. -

Western Samoa Mangrove Fish Survey

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Horizon / Pleins textes RAPPORTS DE MISSIONS SCIENCES DE LA MER BIOLOGIE MARINE 1993 Western Samoa mangrove fish survey Poissons de mangrove des Samoa Occidentales Mission d'expertise du 25/11/1992 au 05/12/1992 Rapport final Pierre THOLLOT Document de travail l'lNSTmJT FRANCAIS DE RECHERCHE SCIENTFûlJE ~il POUR LE DEVELoPPEMENT EN COOPERATION ~ CENTRE DE NOUMÉA RAPPORTS DE MISSIONS SCIENCES DE LA MER BIOLOGIE MARINE 1993 Western Samoa mangrove fish survey Poissons de mangrove des Samoa Occidentales Mission d'expertise du 25/11/1992 au 0511211992 Rapport final Pierre THOLLOT " ..... " .. ",..",.", . ," ~- -: - ~; - <:; ~" ...•. L'lNSTnUf FRANCAIS DE REŒfERCI-E SClENTlFOJE POUR LE DEVELOPPEMENT EN COOPERATION CENTRE DE NOUMÉA © ORSTOM, Nouméa, 1993 rrhollot, P. Western Samoa mangrove fish survey. Poissons de mangrove des Samoa OCcidentales Mission d'expertise du 25/1111992 au 05/1211992 Rapport final Nouméa: ORSTOM. septembre1993. 28 p. missions. : Sci. mer: Biot. Mar. ; 23 036MILMAR ; 034BIOVER01 ICHTYOLOGIE; MANGROVE; INVENTAIRE FAUNISTIQUE ; COMMUNAUTE DE POISSON; MILIEU MENACE; POISSON MARIN; MILIEU L1TIORAL; METHODE D'ECHANTILLONAGE; ETUDE CONPARATIVE ISAMOA OCCIDENTAL Imprimé par le Centre ORSTOM Seplembre1993 ~~RSTO" lIoum'. lt:I REPROGRAPHIE -Western Samoa Mangrove Fish Survey - Final Report- SUMMARY EXECU11VE SUMMARy 2 roREWORD 3 BACK.GROlJND 3 MAIN GOALS 3 PRESEN'I'ATION OF TlŒ S11IDY AREA 4 MA1'ERIAL AND ~ODS 6 Survey cœnpletion 6 Sampling equipment '" , 7 Sampling stations '" 7 Biological data 8 RESlJLTS AND DISœSSION 9 Preliminary checklist of the mangrove fish fauna 9 Comparison of Sa'anapu-Sataoa and Vaiusu Bay sampling statïons l0 Comparison of the sampling methods 11 Biological data 13 TllE()REIlCAL ADVICE 13 CONO-USION : 14 REFER.EN'CES 15 APPENDIX 1 17 APPENDIX fi 22 APPENDIX m 25 APPENDIX IV 28 - 1- • Pierre THOU.OT . -

Village Residential District Model Ordinance

Montgomery County, Pennsylvania Creating a Village Community village residential district Montgomery County Board of Commissioners Josh Shapiro, Chair Leslie S. Richards, Vice Chair Bruce L. Castor, Jr., Commissioner Montgomery County Planning Commission Board P. Gregory Shelly, Chair Scott Exley, Vice Chair Dulcie F. Flaharty Henry P. Jacquelin Pasquale N. Mascaro Roy Rodriguez, Jr. Charles J. Tornetta V. Scott Zelov Steven L. Nelson, Director village residential district Creating a Village Community Prepared by the Montgomery County Planning Commission 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................1 The Village Residential Development Concept What is the Village Residential District? .................................................................................5 Why Have a Village Residential District?................................................................................6 What Will a Village Residential Development Look Like? ......................................................8 Local Examples ......................................................................................................................9 Planning for Village Residential Development Where Should the Village Residential District Be Used?......................................................13 Suitable Location - Infill Within a Village...............................................................................14 Suitable Location -

2016 CENSUS Brief No.1

P O BOX 1151 TELEPHONE: (685)62000/21373 LEVEL 1 & 2 FMFM II, Matagialalua FAX No: (685)24675 GOVERNMENT BUILDING Email: [email protected] APIA Website: www.sbs.gov.ws SAMOA 2016 CENSUS Brief No.1 Revised version Population Snapshot and Household Highlights 30th October 2017 1 | P a g e Foreword This publication is the first of a series of Census 2016 Brief reports to be published from the dataset version 1, of the Population and Housing Census, 2016. It provides a snapshot of the information collected from the Population Questionnaire and some highlights of the Housing Questionnaire. It also provides the final count of the population of Samoa in November 7th 2016 by statistical regions, political districts and villages. Over the past censuses, the Samoa Bureau of Statistics has compiled a standard analytical report that users and mainly students find it complex and too technical for their purposes. We have changed our approach in the 2016 census by compiling smaller reports (Census Brief reports) to be released on a quarterly basis with emphasis on different areas of Samoa’s development as well as demands from users. In doing that, we look forward to working more collaboratively with our stakeholders and technical partners in compiling relevant, focused and more user friendly statistical brief reports for planning, policy-making and program interventions. At the same time, the Bureau is giving the public the opportunity to select their own data of interest from the census database for printing rather than the Bureau printing numerous tabulations which mostly remain unused. -

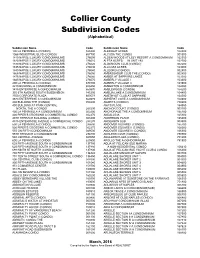

Collier County Subdivision Code List

Collier County Subdivision Codes (Alphabetical) Subdivision Name Code Subdivision Name Code 100 LA PENINSULA (CONDO) 528400 ALBRIGHT ACRES 162400 1068 INDUSTRIAL BLVD (CONDO) 657700 ALCOSA THE CONDO 001900 1810 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276000 ALDEN WOODS AT LELY RESORT A CONDOMINIUM 162550 1820 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276010 ALETA ACRES IN UNIT 193 162700 1830 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276020 ALGONQUIN CLUB (CONDO) 002200 1835 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276030 ALLCOAT ACRES 163000 1840 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276040 ALLEGRO (CONDO) 002500 1865 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276050 AMBASSADOR CLUB THE (CONDO) 002800 1875 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276060 AMBER AT SAPPHIRE LAKES 163300 1885 NAPOLI LUXURY CONDOMINIUMS 276070 AMBERLY VILLAGE I 163600 200 LA PENINSULA (CONDO) 677800 AMBERLY VILLAGE II 163900 2210 BUILDING A CONDOMINIUM 653450 AMBERTON A CONDOMINIUM 164050 3435 ENTERPRISE A CONDOMINIUM 660570 AMBLEWOOD (CONDO) 164200 350 6TH AVENUE SOUTH SUBDIVISION 145250 AMELIA LAKE A CONDOMINIUM 164400 3500 CORPORATE PLAZA 660573 AMETHYST CLUB AT SAPPHIRE 164500 3573 ENTERPRISE A CONDOMINIUM 660575 AMHERST COVE A CONDOMINIUM 164800 400 BUILDING THE (CONDO) 050200 ANAHITA (CONDO) 750600 400 BUILDING AT PARK CENTRAL ANA'S PLACE 164950 NORTH, THE A CONDO 283230 ANCHOR COURT (CONDO) 003100 400 LA PENINSULA A CONDOMINIUM 302200 ANCHORAGE THE A CONDOMINIUM 165100 400 PIPER'S CROSSING A COMMERCIAL CONDO 302270 ANDALUCIA 165300 40TH TERRACE BUILDING (CONDO) 303400 ANDERSON PLACE 165400 4375 ENTERPRISE AVENUE A COMMERCIAL CONDO 283270 ANDERSON -

The Soils and Agriculture of Western Samoa

DEPARTMENT OF SCIENTIFIC AND .NDUSTRIAL RESEARCH. BULLETIN No. 61. The Soils· and Agriculture of Western Samoa. BY --W. M. HAMILTON AND L. I. GRANGE, Departn1ent of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Zealand. under the authority of the Hon: D. G. SULJ,,IVAN, · Minister of Scientific and Industrial Research. Extracted from the. N tiW Zealand Journal of Science and Tecknology, Vol. XIX; . No. 10, pp. 593-624, 1938, . WELLINGTON, .N.Z . E V. PAUL, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, 593 THE SOILS AND AGRICULTURE OF WESTERN SAMOA. By W. M. HAMILTON* and L. I. GRANGEt, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Zealand. PAGE SUMMARY 594 INTRODUCTION 594 CLIMATE 595 THE SOILS OF SAMOA- Topography 595 Factors in Soil D.evelopment 596 Descriptions of Soil Series 597 Classification in relation to Chemical Analysis 600 Soil Nutrients 601 Physical Condition of the Soils : . 602 Soil Erosion 602 THE MAJOR CROPS GROWN General 603 Coconuts Production Trends 603 General Condition of the Plantations 604 Rooting of Coconut-palms .. 605 Rhinoceros Beetle (Oryctes rhinocero.s) 606 Methods of Harvesting, &c. 606 Types planted 607 Decadent Areas 610 Manuring 611 General 612 Cocoa Production and Types planted 613 Black-pod Disease (Phytophthora palmivora) .. 616 Cultural Methods 616 Rooting of Cocoa-trees 617 Manuring 617 General 619 Bananas .~ Production and Cultural Conditions .. '. 619 Varieties 620 Harvesting and Shipping 620 General 621 Papain 622 Rubber 622 Coffee 622 OTHER CROPS NOT GROWN ON A COMMERCIAL BASIS 622 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 623 REFERE!WES 624 • Assistant Professional Officer. t Director, Soil Survey Division 594 THE N.Z. JOURNAL _OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY. [MARCH Summary. -

MH-ICP-MS Analysis of the Freshwater and Saltwater Environmental Resources of Upolu Island, Samoa

Supplementary Materials (SM) MH-ICP-MS Analysis of the Freshwater and Saltwater Environmental Resources of Upolu Island, Samoa Sasan Rabieh 1,*, Odmaa Bayaraa 2, Emarosa Romeo 3, Patila Amosa 4, Khemet Calnek 1, Youssef Idaghdour 2, Michael A. Ochsenkühn 5, Shady A. Amin 5, Gary Goldstein 6 and Timothy G. Bromage 1,7,* 1 Department of Molecular Pathobiology, New York University College of Dentistry, 345 East 24th Street, New York, NY 10010, USA; [email protected] (K.C.) 2 Environmental Genomics Lab, Biology Program, Division of Science and Mathematics, New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island, PO Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; [email protected] (O.B.); [email protected] (Y.I.) 3 Hydrology Division, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Level 3, Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Efi Building (TATTE), Sogi., P.O. Private Bag, Apia, Samoa; [email protected] (E.R.) 4 Faculty of Science, National University of Samoa, PO Box 1622, Apia, Samoa; [email protected] (P.A.) 5 Marine Microbial Ecology Lab, Biology Program, New York University Abu Dhabi, Saadiyat Island, PO Box 129188, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; [email protected] (M.A.O.); [email protected] (S.A.A.) 6 College of Dentistry, New York University, 345 East 24th Street, New York, NY 10010, USA; [email protected] (G.G.) 7 Department of Biomaterials, New York University College of Dentistry, 345 East 24th Street, New York, NY 10010, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.R.); [email protected] (T.G.B.); Tel.: +1-212-998-9638 (S.R.); +1- 212-998-9597 (T.G.B.) Academic Editors: Zikri Arslan and Michael Bolshov Received: 16 August 2020; Accepted: 19 October 2020; Published: date Table S1.