Breaking out of the Governance Trap in Rural Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

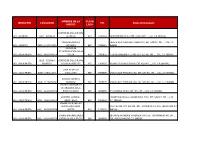

MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE LA UNIDAD CLAVE LADA TEL Domiciliocompleto

NOMBRE DE LA CLAVE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD TEL DomicilioCompleto UNIDAD LADA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 001 - ACONCHI 0001 - ACONCHI ACONCHI 623 2330060 INDEPENDENCIA NO. EXT. 20 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84920) CASA DE SALUD LA FRENTE A LA PLAZA DEL PUEBLO NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. 001 - ACONCHI 0003 - LA ESTANCIA ESTANCIA 623 2330401 (84929) UNIDAD DE DESINTOXICACION AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 3382875 7 ENTRE AVENIDA 4 Y 5 NO. EXT. 452 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) 0013 - COLONIA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 002 - AGUA PRIETA MORELOS COLONIA MORELOS 633 3369056 DOMICILIO CONOCIDO NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) CASA DE SALUD 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0009 - CABULLONA CABULLONA 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84305) CASA DE SALUD EL 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0046 - EL RUSBAYO RUSBAYO 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84306) CENTRO ANTIRRÁBICO VETERINARIO AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA SONORA 999 9999999 5 Y AVENIDA 17 NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) HOSPITAL GENERAL, CARRETERA VIEJA A CANANEA KM. 7 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA AGUA PRIETA 633 1222152 C.P. (84250) UNEME CAPA CENTRO NUEVA VIDA AGUA CALLE 42 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , AVENIDA 8 Y 9, COL. LOS OLIVOS C.P. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 1216265 (84200) UNEME-ENFERMEDADES 38 ENTRE AVENIDA 8 Y AVENIDA 9 NO. EXT. SIN NÚMERO NO. -

Colegio De Estudios Científicos Y Tecnológicos Del Estado De Sonora

Programa Institucional de Mediano Plazo 2011-2015 Colegio de Estudios Científicos y Tecnológicos del Estado de Sonora Programa Institucional de Mediano Plazo 2010-2015 Hermosillo, Sonora, Noviembre de 2010 1 Directorio CECyTES Sonora Lic. Guillermo Padrés Elías Gobernador del Estado de Sonora. H. Junta Directiva Mtro. Jorge Luis Ibarra Mendivil Secretario de Educación y Cultura, Presidente de la H. Junta Directiva. Lic. Clementina Elías Córdova Presidenta del Voluntariado del DIF Sonora, Representante del Gobierno del Estado de Sonora. Ing. Jesús Eduardo Chávez Leal Titular de Oficina de Servicios Federales de Apoyo a la Educación de Sonora, Representante del Gobierno Federal. Ing. Celso Gabriel Espinosa Corona Coordinador Nacional de Organismos Descentralizados Estatales de los CECyTE’s, Representante del Gobierno Federal. Lic. Luis Sierra Abascal Representante del Sector Social. Lic. Luis Carlos Durán Ríos Comisario Publico Ciudadano, Representante del Sector Social. Ing. Enrique Tapia Camou Representante del Sector Productivo. C.P. Luis Carlos Contreras Tapia Representante del Sector Productivo. Lic. Mario Alberto Corona Urquijo Titular del Órgano de Control y Desarrollo Administrativo en CECyTES Sonora. Mtro. Martín Alejandro López García Director General de CECyTES, Secretario Técnico de la H. Junta Directiva. M.C. José Carlos Aguirre Rosas Director Académico Ing. José Francisco Arriaga Moreno Director de Administración Profr. Gerardo Gaytán Fox Directora de de Vinculación Lic. Alfredo Ortega López Director de Planeación Lic. Jesús Carlos Castillo Rosas Secretario Particular Mtro. José Francisco Bracamonte Fuentes Secretario Técnico 2 Directores de Plantel Ing. Jazmín Guadalupe Navarro Garate CECyTES Bacame Lic. Juan José Araiza Rodríguez CECyTES Santa Ana Lic. Alma Flor Atondo Obregón CECyTES Ej. -

1 Er Informe De Gobierno

1er INFORME DE ACTIVIDADES H. AYUNTAMIENTO DE SAHUARIPA, SONORA 1 1ER INFORME DE ACTIVIDADES 2015 – 2018 H. Ayuntamiento de Sahuaripa 2015-2018 C.P. Plutarco Guadalupe Trejo Vázquez Presidente Municipal C. Delia Berenice Porchas García Secretario del H. Ayuntamiento C. Rodolfo Ruiz Robles Tesorero Municipal C. P. Lorena Rascón Bermúdez Sindico Procurador Regidores Francisco Javier Paredes López Claudia Ivoneth Soria García Adalberto Arvayo Valencia Raúl Francisco Cota Arrieta Heremita Amado Miranda 2 1ER INFORME DE ACTIVIDADES 2015 – 2018 CONTENIDO I. PRESENTACIÓN II. MARCO JURÍDICO III. MISIÓN, VISIÓN VALORES IV. ASPECTOS DEMOGRÁFICOS V. MARCO GENERAL VI. DIRECTRIZ 1 DESARROLLO SOCIAL Y SERVICIOS PÚBLICOS VII. DIRECTRIZ 2 EMPLEO Y ECONOMÍA VIII. DIRECTRIZ 3 DESARROLLO URBANO Y CRECIMIENTO MUNICIPAL IX. DIRECTRIZ 4 SAHUARIPA SEGURO PARA TODOS X. DIRECTRIZ 5 BUEN GOBIERNO, INNOVADOR Y DE RESULTADOS 3 1ER INFORME DE ACTIVIDADES 2015 – 2018 PRESENTACIÓN 4 1ER INFORME DE ACTIVIDADES 2015 – 2018 MARCO JURÍDICO Con el 1er informe de Gobierno de la Administración 2015- 2018 del municipio de Sahuaripa, damos cumplimiento a lo dispuesto en el artículo 136, fracción XXVII, de la Constitución Política del Estado Libre y Sobernado de Sonora, así como lo establecido en los artículos 61 y 65, fracciones III y IX, inciso X respectivamente, de la ley de Gobierno y Administración Municipal. 5 1ER INFORME DE ACTIVIDADES 2015 – 2018 MISIÓN El H. Ayuntamiento de Sahuaripa, es una institución que busca el desarrollo integral entre sus habitantes, prestando servicios de calidad con una atención amable, moderna, profesional y eficiente, siempre apegada a la legalidad, promoviendo la participación de todos para preservar una cordial convivencia; el respeto a la cultura y tradiciones en un marco de austeridad y respeto. -

Administracion Municipal 2018 - 2021

ADMINISTRACION MUNICIPAL 2018 - 2021 ACONCHI (Coalición PRI-VERDE-NUEVA ALIANZA) Presidente Municipal CELIA NARES LOERA Dirección Obregón y Pesqueira #132 Col. Centro, Ayuntamiento Aconchi, Sonora Tel. Oficina 01 623 233-01-39 233-01-55 Tel. Particular Celular Email Presidenta DIF C. DAMIAN EFRAIN AGUIRRE DEGOLLADO Dirección DIF Obregón y Pesqueira #132 Col. Centro, Aconchi, Sonora Tel. DIF 01 623 233-01-39 ext 112 01 (623) 23 30 001 Celular Email [email protected] Cumpleaños [email protected] Director DIF SRA. Evarista Soto Duron Celular Email [email protected] Email oficial ADMINISTRACION MUNICIPAL 2018 - 2021 AGUA PRIETA (Coalición MORENA – PT – ENCUENTRO SOCIAL) Presidente Municipal ING. JESÚS ALFONSO MONTAÑO DURAZO Dirección Calle 6 y 7 e/Ave. 16 y 17 Col. Centro CP Ayuntamiento 84200, Agua Prieta, Sonora Tel. Oficina 01 633 338-94-80 ext. 2 333-03-80 Tel. Particular Celular Srio. Particular Mtro. Juan Encinas Email: [email protected] Presidenta DIF SRA. MARIA DEL CARMEN BERNAL LEÓN DE MONTAÑO Dirección DIF Calle 4 Ave. 9 y 10 Col. Centro CP 84200, Agua Prieta, Sonora Tel. DIF 01 633 338-20-24 338-27-31 338-42-73 Celular Email cumpleaños Director DIF MTRA. AURORA SOLANO GRANADOS Celular Email [email protected] Cumpleaños ADMINISTRACION MUNICIPAL 2018 - 2021 ALAMOS (Coalición PRI-VERDE-NUEVA ALIANZA) Presidente Municipal VÍCTOR MANUEL BALDERRAMA CÁRDENAS Dirección Calle Juárez s/n Col. Centro, Álamos, Sonora Ayuntamiento Tel. Oficina 01 647 428-02-09 647 105-49-16 Tel. Particular Celular Email Presidenta DIF SRA. ANA REBECA BARRIGA GRAJEDA DE BALDERRAMA Dirección DIF Madero s/n Col. -

Notes on the Winter Avifauna of Two Riparian Sites in Northern Sonora, Mexico

11 Notes on the Winter Avifauna of Two Riparian Sites in Northern Sonora, Mexico SCOTT 8. TERRILL Explorations just south of the border yield some intriguing comparisons to the winter birdlife of the southwestern U.S.: some continuums, some contrasts FOR MANY YEARS the region of the border between Mexico and the United States has been relatively well known in terms of bird species distribution. This is especially true in southeastern Arizona, southernmost Texas and southwestern California. In the first two cases, the ecological communities of these areas are unique in the United States. This offers the birder an opportunity to observe what are essentially tropical and sub-tropical species within U.S. boundaries. The border area in southwestern California (i.e., San Diego - Imperial Beach area) is heavily birded due to a relatively high probability of encountering "vagrant" transients, a somewhat diffe rent situation. Unfortunately, most of this border area coverage has been unilateral. The reasons for this are straightforward: bird listers are concerned with recording species within the standardized A.O. U. Check-list area; observers in general prefer to observe these birds and natural communities in the socially comfortable confines of their native country; birders headed south of the border are usually eager to reach more southerly latitudes where the species represent a greater difference from those of the U.S.; and fi nally, most interested persons would predict that the border areas of Mexico would support avifaunas quite similar to those just north of the border. During the winter of 1979- 1 980, Ken Rosenberg, Gary Rosenberg and I undertook some field work in northern Sonora. -

Spain's Arizona Patriots in Its 1779-1783 War

W SPAINS A RIZ ONA PA TRIOTS J • in its 1779-1783 WARwith ENGLAND During the AMERICAN Revolutuion ThirdStudy of t he SPANISH B ORDERLA NDS 6y Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough ~~~i~!~~¸~i ~i~,~'~,~'~~'~-~,:~- ~.'~, ~ ~~.i~ !~ :,~.x~: ~S..~I~. :~ ~-~;'~,-~. ~,,~ ~!.~,~~~-~'~'~ ~'~: . Illl ........ " ..... !'~ ~,~'] ." ' . ,~i' v- ,.:~, : ,r~,~ !,1.. i ~1' • ." ~' ' i;? ~ .~;",:I ..... :"" ii; '~.~;.',',~" ,.', i': • V,' ~ .',(;.,,,I ! © Copyright 1999 ,,'~ ;~: ~.~:! [t~::"~ "~, I i by i~',~"::,~I~,!t'.':'~t Granville W. and N.C. Hough 3438 Bahia blanca West, Aprt B Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 k ,/ Published by: SHHAR PRESS Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 http://mcmbers.aol.com/shhar SHHARPres~aol.com (714) $94-8161 ~I,'.~: Online newsletter: http://www.somosprimos.com ~" I -'[!, ::' I ~ """ ~';I,I~Y, .4 ~ "~, . "~ ! ;..~. '~/,,~e~:.~.=~ ........ =,, ;,~ ~c,z;YA':~-~A:~.-"':-'~'.-~,,-~ -~- ...... .:~ .:-,. ~. ,. .... ~ .................. PREFACE In 1996, the authors became aware that neither the NSDAR (National Society for the Daughters of the American Revolution) nor the NSSAR (National Society for the Sons of the American Revolution) would accept descendants of Spanish citizens of California who had donated funds to defray expenses ,-4 the 1779-1783 war with England. As the patriots being turned down as suitable ancestors were also soldiers,the obvious question became: "Why base your membership application on a money contribution when the ancestor soldier had put his life at stake?" This led to a study of how the Spanish Army and Navy had worked during the war to defeat the English and thereby support the fledgling English colonies in their War for Independence. After a year of study, the results were presented to the NSSAR; and that organization in March, 1998, began accepting descendants of Spanish soldiers who had served in California. -

GASTOS DE VIAJE COMBUSTIBLE Y CASETAS DE PEAJE DE 01-Mayo-2017 a 31-Mayo-2017

GASTOS DE VIAJE COMBUSTIBLE Y CASETAS DE PEAJE DE 01-mayo-2017 A 31-mayo-2017 GASTOS DE GASTOS DE NOMBRE Y CARGO MOTIVO Y COMISION COMBUSTIBLE CASETAS DE PEAJE ACOSTA COTA MARIO ENRIQUE COORD. DE PROGRAMAS ALIMENTARIOS PROGRAMA DE DESAYUNOS ESCOLARES 15-mayo-2017 REQUERIDO PARA LLEVAR A CABO LA ENTREGA DE LOS 5,760.49 71.00 CONVENIOS DE COORDINACION PARA LA OPERACION DEL PROGRAMA DESAYUNOS ESCOLARES Y ASISTENCIA ALIMENTARIA A SUJETOS VULNERABLES DEBIDAMENTE FIRMADO, ENTREGA DE ADENDUM AL PROGRAMA DESAYUNOS ESCOLARES PARA SU FIRMA, CORRESPONDIENTE AL EJERCICIO FISCAL 2017, EN LOS MUNICIPIOS DE MAZATAN, VILLA PESQUEIRA, SAN PEDRO DE LA CUEVA, BACANORA, SOYOPA, SAHUARIPA, ARIVECHI, YECORA, ROSARIO, ONAVAS, SAN JAVIER, SUAQUI GRANDE, LA COLORADA, GUAYMAS, EMPALME, CAJEME, ALAMOS, NAVOJOA, ETCHOJOA, HUATABAMPO, BENITO JUAREZ, SAN IGNACIO RIO MUERTO Y BACUM. ASI COMO LA SUPERVISION DE LOS PROGRAMAS DESAYUNOS ESCOLARES Y DESPENSAS EN LOS MUNICIPIOS DE ONAVAS, SAN JAVIER, SUAQUI GRANDE Y LA COLORADA. MAZATAN Sonora VILLA PESQUEIRA Sonora SAN PEDRO LA CUEVA Sonora BACANORA Sonora SOYOPA Sonora SAHUARIPA Sonora ARIVECHI Sonora YECORA Sonora *La información publicada contiene cifras preliminares. Dirección de Planeación y Finanzas *En la columna Total Gastado el importe en $0.00 es por el reintegro del efectivo. 1 21/09/2017 GASTOS DE VIAJE COMBUSTIBLE Y CASETAS DE PEAJE DE 01-mayo-2017 A 31-mayo-2017 GASTOS DE GASTOS DE NOMBRE Y CARGO MOTIVO Y COMISION COMBUSTIBLE CASETAS DE PEAJE ROSARIO DE TESOPACO Sonora SAN JAVIER Sonora SUAQUI GRANDE Sonora LA COLORADA Sonora GUAYMAS Sonora EMPALME Sonora CAJEME Sonora ALAMOS Sonora NAVOJOA Sonora ETCHOJOA Sonora HUATABAMPO Sonora BENITO JUAREZ Sonora SAN IGNACIO RIO MUERTO Sonora BACUM Sonora ONAVAS Sonora ARCE FIGUEROA FELIX JULIAN ASESOR JURIDICO PROC DE PROT DE NIÑAS NIÑOS Y ADOL 11-mayo-2017 ASISTIR A CURSO "IMPARTICIÓN DE JUSTICIA 0.00 300.00 PARA ADOLESCENTES". -

Sonora, Mexico

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development SONORA, MEXICO, Sonora is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico and has made great strides in Sonora, building its human capital and skills. How can Sonora turn the potential of its universities and technological institutions into an active asset for economic and Mexico social development? How can it improve the equity, quality and relevance of education at all levels? Jaana Puukka, Susan Christopherson, This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional Patrick Dubarle, Jocelyne Gacel-Ávila, reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. Sonora, Mexico CONTENTS Chapter 1. Human capital development, labour market and skills Chapter 2. Research, development and innovation Chapter 3. Social, cultural and environmental development Chapter 4. Globalisation and internationalisation Chapter 5. Capacity building for regional development ISBN 978- 92-64-19333-8 89 2013 01 1E1 Higher Education in Regional and City Development: Sonora, Mexico 2013 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PRELIMINARY DEPOSIT-TYPE MAP of NORTHWESTERN MEXICO by Kenneth R

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PRELIMINARY DEPOSIT-TYPE MAP OF NORTHWESTERN MEXICO By Kenneth R. Leonard U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 89-158 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Any use of trade, product, firm, or industry names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Menlo Park, CA 1989 Table of Contents Page Introduction..................................................................................................... i Explanation of Data Fields.......................................................................... i-vi Table 1 Size Categories for Deposits....................................................................... vii References.................................................................................................... viii-xx Site Descriptions........................................................................................... 1-330 Appendix I List of Deposits Sorted by Deposit Type.............................................. A-1 to A-22 Appendix n Site Name Index...................................................................................... B-1 to B-10 Plate 1 Distribution of Mineral Deposits in Northwestern Mexico Insets: Figure 1. Los Gavilanes Tungsten District Figure 2. El Antimonio District Figure 3. Magdalena District Figure 4. Cananea District Preliminary Deposit-Type Map of -

Report on the Sonora Lithium Project

Report on the Sonora Lithium Project (Pursuant to National Instrument 43-101 of the Canadian Securities Administrators) Huasabas - Bacadehuachi Area (Map Sheet H1209) Sonora, Mexico o o centered at: 29 46’29”N, 109 6’14”W For 330 – 808 – 4th Avenue S. W. Calgary, Alberta Canada T2P 3E8 Tel. +1-403-237-6122 By Carl G. Verley, P. Geo. Martin F. Vidal, Lic. Geo. Geological Consultant Vice-President, Exploration Amerlin Exploration Services Ltd. Bacanora Minerals Ltd. 2150 – 1851 Savage Road Calle Uno # 312 Richmond, B.C. Canada V6V 1R1 Hermosillo, Mexico Tel. +1-604-821-1088 Tel. +52-662-210-0767 Ellen MacNeill, P.Geo. Geological Consultant RR5, Site25, C16 Prince Albert, SK Canada S6V 5R3 Tel. +1-306-922-6886 Dated: September 5, 2012. Bacanora Minerals Ltd. Report on the Sonora Lithium Project, Sonora, Mexico Date and Signature Page Date Dated Effective: September 5, 2012. Signatures Carl G. Verley, P.Geo. ____________________ Martin F. Vidal, Lic. Geo. Ellen MacNeill, P.Geo. Amerlin Exploration Services Ltd. - Consulting mineral exploration geologists ii Bacanora Minerals Ltd. Report on the Sonora Lithium Project, Sonora, Mexico Table of Contents 1.0 Summary ................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 3.0 Reliance on Other Experts ....................................................................................................... -

84920 Sonora 7226001 Aconchi Aconchi 84923 Sonora 7226001 Aconchi Agua Caliente 84923 Sonora 7226001 Aconchi Barranca Las Higuer

84920 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI ACONCHI 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI AGUA CALIENTE 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI BARRANCA LAS HIGUERITAS 84929 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI CHAVOVERACHI 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI EL RODEO (EL RODEO DE ACONCHI) 84925 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI EL TARAIS 84929 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI ESTABLO LOPEZ 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI HAVINANCHI 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA ALAMEDA 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA ALAMEDITA 84929 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA ESTANCIA 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA HIGUERA 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA LOMA 84929 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA MISION 84933 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LA SAUCEDA 84924 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LAS ALBONDIGAS 84930 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LAS GARZAS 84924 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI LOS ALISOS 84930 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI MAICOBABI 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI RAFAEL NORIEGA SOUFFLE 84925 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI REPRESO DE ROMO 84928 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI SAN PABLO (SAN PABLO DE ACONCHI) 84934 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI TEPUA (EL CARRICITO) 84923 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI TRES ALAMOS 84935 SONORA 7226001 ACONCHI VALENCIA 84310 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA 18 DE AGOSTO (CORRAL DE PALOS) 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ABEL ACOSTA ANAYA 84270 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ACAPULCO 84313 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ADAN ZORILLA 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ADOLFO ORTIZ 84307 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA AGUA BLANCA 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ALBERGUE DIVINA PROVIDENCIA 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ALBERTO GRACIA GRIJALVA 84303 SONORA 7226002 AGUA PRIETA ALFONSO GARCIA ROMO 84303 SONORA -

PERFORACIÓN Y EQUIPAMIENTO DE POZOS GANADEROS EJERCICIO 2014 Municipio De Empleos Tipo Localidad De Apoyo Federal Cantidad Cantidad Estado Folio Solicitud Nombre(S) A

PADRÓN DE BENEFICIARIOS PROGRAMA DE FOMENTO GANADERO COMPONENTE: PERFORACIÓN Y EQUIPAMIENTO DE POZOS GANADEROS EJERCICIO 2014 Municipio de Empleos Tipo Localidad de Apoyo Federal Cantidad Cantidad Estado Folio Solicitud Nombre(s) A. paterno A. materno DDR CADER Aplicación de Caracteristicas Generados Solicitante Aplicación de Proyecto (Autorizado) Hombres Mujeres Proyecto Directos SONORA SR1400009896 FISICA JESUS ALBERTO DICOCHEA AGUILAR MAGDALENA NOGALES NOGALES HEROICA NOGALES PERFORACION DE POZO 8" $ 167,400.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009896 FISICA JESUS ALBERTO DICOCHEA AGUILAR MAGDALENA NOGALES NOGALES HEROICA NOGALES TUBERIA PVC CEDULA 40 $ 18,461.47 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009902 FISICA CARLOS ROBLES GRIJALVA URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN PILA ARMABLE $ 81,080.06 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009902 FISICA CARLOS ROBLES GRIJALVA URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN PERFORACION DE POZO $ 165,000.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009902 FISICA CARLOS ROBLES GRIJALVA URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN LINEA DE CONDUCCION DE AGUA $ 41,777.04 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009909 FISICA ENRIQUE ALONSO SALCIDO MONTAÑO URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN EQUIPO DE BOMBEO $ 34,641.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009909 FISICA ENRIQUE ALONSO SALCIDO MONTAÑO URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN PERFORACION DE POZO $ 119,700.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400009914 FISICA FLORENCIO CRUZ BURROLA URES URES RAYÓN RAYÓN PERFORACION DE POZO $ 123,000.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400010642 FISICA CESAR NAVARRO CRUZ URES BANAMICHI BAVIÁCORA BAVIÁCORA BOMBA SUMERGIBLE $ 7,200.00 0 0 0 SONORA SR1400010642 FISICA CESAR NAVARRO CRUZ URES BANAMICHI BAVIÁCORA BAVIÁCORA PERFORACION DE POZO $