Seeking Information About South Africa's Nuclear Energy Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2013) New Contree, No

New Contree, No. 66 (July 2013) New Contree, No. 66 (July 2013) New Contree, No. 66 (July 2013) New Contree No. 66, July 2013 A journal of Historical and Human Sciences for Southern Africa New Contree, No. 66 (July 2013) New Contree is an independent peer-reviewed journal indexed by the South African Department of Higher Education and Training. New Contree is a multidisciplinary focussed peer reviewed journal within the Historical and Human Sciences administrated by the School of Basic Sciences, Vaal Triangle Campus, North-West University. To accommodate more articles from a wide variety of Historical and Human Sciences disciplines (that especially reflect a fundamental historical approach), this Journal has slightly altered its name from 2008. Opinions expressed or conclusions arrived at in articles and book reviews are those of the authors and are not to be regarded as those of the North-West University or the Editorial Advisory Committee of New Contree. Two editions of New Contree are annually published (July and December), and one special issue annually as from 2012. The annual special issue (published in October as from 2013) mainly caters for research disseminations related to local and/or regional history in especially Southern Africa (covering any aspect of activity and phenomenon analysis within the context of for example urban, rural, social, cultural, health, environmental and political life). Researchers from any institution are encouraged to communicate with the editor and editorial team if they are interested to act as guest editor for a special issue. Articles appearing in New Contree are abstracted and/or indexed in Index to South African periodicals, Historical Abstracts, and America: History and Life. -

Country Guide South Africa

Human Rights and Business Country Guide South Africa March 2015 Table of Contents How to Use this Guide .................................................................................. 3 Background & Context ................................................................................. 7 Rights Holders at Risk ........................................................................... 15 Rights Holders at Risk in the Workplace ..................................................... 15 Rights Holders at Risk in the Community ................................................... 25 Labour Standards ................................................................................. 35 Child Labour ............................................................................................... 35 Forced Labour ............................................................................................ 39 Occupational Health & Safety .................................................................... 42 Trade Unions .............................................................................................. 49 Working Conditions .................................................................................... 56 Community Impacts ............................................................................. 64 Environment ............................................................................................... 64 Land & Property ......................................................................................... 72 Revenue Transparency -

And YOU Will Be Paying for It Keeping the Lights On

AFRICA’S BEST READ October 11 to 17 2019 Vol 35 No 41 mg.co.za @mailandguardian Ernest How rugby After 35 Mancoba’s just can’t years, Africa genius give has a new acknowledged racism tallest at last the boot building Pages 40 to 42 Sport Pages 18 & 19 Keeping the lights on Eskom burns billions for coal And YOU will be paying for it Page 3 Photo: Paul Botes Zille, Trollip lead as MIGRATION DA continues to O Visa row in Vietnam Page 11 OSA system is ‘xenophobic’ Page 15 tear itself apart OAchille Mbembe: No African is a foreigner Pages 4 & 5 in Africa – except in SA Pages 28 & 29 2 Mail & Guardian October 11 to 17 2019 IN BRIEF ppmm Turkey attacks 409.95As of August this is the level of carbon Kurds after Trump Yvonne Chaka Chaka reneges on deal NUMBERS OF THE WEEK dioxide in the atmosphere. A safe number Days after the The number of years Yvonne Chaka is 350 while 450 is catastrophic United States Chaka has been married to her Data source: NASA withdrew troops husband Dr Mandlalele Mhinga. from the Syria The legendary singer celebrated the border, Turkey Coal is king – of started a ground and couple's wedding anniversary this aerial assault on Kurdish week, posting about it on Instagram corruption positions. Civilians were forced to fl ee the onslaught. President Donald Trump’s unex- Nigeria's30 draft budget plan At least one person dies every single day so pected decision to abandon the United States’s that we can have electricity in South Africa. -

South Africa's Impending Nuclear Plans

Briefing Paper 290 May 2012 South Africa’s Impending Nuclear Plans "I think that the amount of money that has been allocated for the nuclear build is not a thumbsuck, and we don't actually think that is the end amount, but we believe that it is the beginning," Energy Minister Dipuo Peters 1. Int roduction 600 MW of new nuclear capacity to be completed between 2023 and 2030.1 The demand for energy continually increases with South Africa’s developing population and This briefing paper aims to highlight some of the economy. Nuclear power has been touted as one key considerations and debates around the of the solutions to meet this ever‐increasing expansion of nuclear power in South Africa. demand especially as, according to its However, government’s proposals are still proponents, it generates electricity in an subject to public participation processes, environmentally responsible manner. South environmental impact assessments and, no Africa’s only nuclear power plant, Koeberg, doubt, potential litigation. The fact that the situated 30km north of Cape Town, consists of finance minister made no reference in his budget two Pressurized Water Reactors better known as speech to the anticipated expenditure of at least EPR units. Each unit has a capacity of 920 R300 billion has added to uncertainty around megawatts (MW) and is cooled by sea‐water. In government’s intentions. It is thus not possible to this system, water inside a pressurised reactor is state with any certainty if, when or where these heated up by uranium fuel in the reactor. High plants will be built, or what they will ultimately temperature, high pressure water is then passed cost. -

Environmentalism in South Africa: a Sociopolitical Perspective Farieda Khan

Macalester International Volume 9 After Apartheid: South Africa in the New Article 11 Century Fall 12-31-2000 Environmentalism in South Africa: A Sociopolitical Perspective Farieda Khan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl Recommended Citation Khan, Farieda (2000) "Environmentalism in South Africa: A Sociopolitical Perspective," Macalester International: Vol. 9, Article 11. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/macintl/vol9/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Global Citizenship at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester International by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Environmentalism in South Africa: A Sociopolitical Perspective FARIEDA KHAN I. Introduction South Africa is a country that has undergone dramatic political changes in recent years, transforming itself from a racial autocracy to a democratic society in which discrimination on racial and other grounds is forbidden, and the principle of equality is enshrined in the Constitution. These political changes have been reflected in the envi- ronmental sector which, similarly, has transformed its wildlife-cen- tered, preservationist approach (appealing mainly to the affluent, white minority), to a holistic conservation ideology which incorporates social, economic, and political, as well as ecological, aspects. Nevertheless, despite the fact -

Africa Regional Workshop, Cape Town South Africa, 27 to 30 June 2016

Africa Regional Workshop, Cape Town South Africa, 27 to 30 June 2016 Report Outline 1. Introduction, and objectives of the workshop 2. Background and Approach to the workshop 3. Selection criteria and Preparation prior to the workshop 4. Attending the National Health Assembly 5. Programme/Agenda development 6. Workshop proceedings • 27 June‐Overview of research, historical context of ill health‐ campaigning and advocacy 28 June‐Capacity building and field visit • June‐ Knowledge generation and dissemination and policy dialogue • June‐ Movement building and plan of action 7. Outcomes of the workshop and follow up plans 8. Acknowledgements Introduction and Objectives of the workshop People’s Health Movement (PHM) held an Africa Regional workshop/International People’s Health University which took place from the 27th to 30 June 2016 at the University of Western Cape (UWC), Cape Town, South Africa. It was attended by approximately 35 PHM members from South Africa, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Benin and Eritrea. The workshop was organised within the framework of the PHM / International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Research project on Civil Society Engagement for Health for All. Objectives for the workshop A four day regional workshop/IPHU took place in Cape Town South Africa at the University of Western Cape, School of Public Health. The objectives of the workshop included: • sharing the results of the action research on civil society engagement in the struggle for Health For All which took place in South Africa and DRC; • to learn more about the current forms/experiences of mobilisation for health in Africa; • to reflect together on challenges in movement building (e.g. -

Nuclear Energy Rethink? the Rise and Demise of South Africa’S Pebble Bed Modular Reactor

Nuclear energy rethink? The rise and demise of South Africa’s Pebble Bed Modular Reactor INTRODUCTION technology to help the US Department of Energy to construct its own version of the high-temperature reactor On 18 February 2010, public enterprises minister Barbara in the USA. Hogan announced that, in line with the 2010 budget, Before leaving the PBMR company, Kriek claimed the South African government had decided to cut its that government will make a decision about the future of financial support to Pebble Bed Modular Reactor (Pty) the PBMR in August 2010.6 This is likely to be part of a Ltd (hereafter the PBMR company). This has probably government pronouncement on nuclear policy in general. put paid to the company’s plans to build a demonstration While the PBMR company has suffered a body blow in model of a locally developed high temperature reactor, the removal of significant state finance, the spectre of its called the pebble bed modular reactor. Its name is such possible renaissance cannot entirely be ruled out for the because it uses a technology involving pebble-shaped moment. We therefore need to understand its history and fuel elements and can be constructed in multiples called prospects. modules. As a result of the curtailing of state funding the Originally the aim of the PBMR project was to deliver company has had to restructure, with plans to dismiss energy to industry and households, both locally and for over 75 per cent of its 800-strong workforce.1 The PBMR export. It was foreseen that it would export 20 reactors company had absorbed R8,67 billion of taxpayers’ money a year and build about ten for domestic use. -

The Treaty of Pelindaba on the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone

UNIDIR/2002/16 The Treaty of Pelindaba on the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Oluyemi Adeniji UNIDIR United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research Geneva, Switzerland NOTE The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. * * * The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. UNIDIR/2002/16 Copyright © United Nations, 2002 All rights reserved UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No. GV.E.03.0.5 ISBN 92-9045-145-9 CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements . vii Foreword by John Simpson . ix Glossary of Terms. xi Introduction. 1 Chapter 1 Evolution of Global and Regional Non-Proliferation . 11 Chapter 2 Nuclear Energy in Africa . 25 Chapter 3 The African Politico-Military Origins of the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone . 35 Chapter 4 The Transition Period: The End of Apartheid and the Preparations for Negotiations . 47 Chapter 5 Negotiating and Drafting the Treaty (Part I): The Harare Meeting . 63 Chapter 6 Negotiating and Drafting the Treaty (Part II): The 1994 Windhoek and Addis Ababa Drafting Meetings, and References where Appropriate to the 1995 Johannesburg Joint Meeting . 71 Chapter 7 Negotiating and Drafting the Treaty (Part III): Annexes and Protocols . 107 Chapter 8 Negotiating and Drafting the Treaty (Part IV): Joint Meeting of the United Nations/OAU Group of Experts and the OAU Inter- Governmental Group, Johannesburg. -

Nuclear Power

RSA | R30.00 incl. VAT TheNuclear Power THE OFFICIAL MOUTHPIECE OF THE SOUTH AFRICAN INSTITUTE OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERS i| JANUARY ssue 2013 wattnow | january 2013 | 1 “Our strength, your advantage” LETTERS 6 Letter from the SAIEE President - Mr Mike Cary. page 14 REGULARS 8 wattshot We showcase gadgets & gizmo's for everyone! 12 wattsup Showcasing social functions & events. page 20 18 Obituary Leslie Harry James - 01-10-1922 - 03-12-2012 58 Membership 61 Crossword - win R1000! 62 SAIEE Calendar of Events page 46 FEATURE 20 Nuclear Power in South Africa Electricity consumption in South Africa has been growing rapidly since 1980 and the country is part of the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP), with extensive interconnections. TECHNOLOGY page 54 30 Enhancing Services with Intelligent Automation We introduce and explain advances in software and hardware. POWER 40 MV Distribution Line Protection utilising Specialised Surge Arrestors Technology Service Excellence We take a look at surge arrestor products manufactured for medium voltage networks. TIS contributes to the success of the power, telecommunications and defence industries by ON A LIGHTER SIDE offering a wide range of products and turnkey solutions. This is complimented by providing 46 Living with an Engineer... network testing, auditing and training to our customers. A tongue-in-cheek look at Angela Price's life growing up, and living with, an engineer. Unit A, 59 Roan Crescent, Corporate Park North, Old Pretoria Road, Randjespark MEMORIES Ext 103, Midrand. PO Box 134, Olifantsfontein, 1665. 52 Reminiscing on an Electrical Engineering career Tel +27(0)11 635 8000 Fax +27(0)11 635 8100 From the pen of Bill Bergman. -

Keep Nuclear Power out of the Cdm (Clean Development Mechanism)

KEEP NUCLEAR POWER OUT OF THE CDM (CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM) Nuclear Power Contradicts Clean Development: Too Little, Too Late, Too Expensive Too Dangerous The Following NGOs Have Joined the Call to Remove "Nuclear Activities" as an Option in the CDM as of 10 December 2008 Women in Europe for a Common Future International Forum on Globalization Greenpeace World Information Service on Energy (WISE) Ecodefense Russia Friends of the Earth International Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS) 8th Day Center for Justice Illinois,USA ACDN (Action des Citoyens pour le Désarmement Nucléaire France AERO—Alternative Energy Resources Organization Montana, USA AGAT Kyrgyzstan Alianza por la Justicia Climatica Chile Alliance for Affordable Energy Louisiana,USA Alliance for Sustainable Communities-Lehigh Valley, Inc. Pennsylvania, USA ALMA-RO Association Romania Alternativa Verda ONG (Green Alternative) Spain/Catalunya Amigos da Terra - Amazônia Brasileira Brazil Amigos de la Tierra/FOE Spain Spain Amis de la Terre - Belgique Belgium Anti Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia Australia Anti Nuclear Alliance of Western Australia (ANAWA) Australia APROMAC - Environment Protection Association Brazil APROMAC - Environment Protection Association Brazil Arab Climate Alliance Lebanon Arizona Safe Energy Coalition Arizona, USA Artists for a Clean Future Asociación Contra Contaminación Ambiental de E.Echeverría Argentina Atomstopp Austria Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) Australia Banktrack Netherlands Bellefonte Efficiency and Sustainaibity -

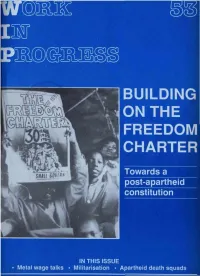

Building on The

wmm mmmsm BUILDING ON THE Towards a post-apartheid constitution IN THIS ISSUE Metal wage talks Militarisation • Apartheid death squads Editorial here is a sense in which government's closure of one newspaper, Tand threatened banning of a number of other publications, is justi fied. This is not because those publications are necessarily guilty of biased or inaccurate journalism, or even because they are in contravention of the over 100 statutes which limit what may be published. Rather, it is because any government which has as much to hide as South Africa's rulers must fear all but the most tame sections of the media. Nearly half of all the editions of Work In Progress produced over ten years were banned under the Publications Act. Yet not once was it suggested that inaccuracy or false information was the reason for banning. In warning Work In Progress that action against the magazine was being contemplated, Stoffel Botha claims to have looked at 24 articles contained in two editions of the magazine. Yet in not one case does he claim that information in an article was false. The conclusion is clear: publications like Work In Progress face closure or pre-publication censorship because of the accuracy of their reporting and analysis. • When an attorney-general declines to prosecute soldiers who kidnap, assault and threaten with death a political activist because the soldiers were acting in terms of emergency regulations; • when a head of state stops the trial of soldiers accused of murdering a Swapo member at a political meeting because -

NPR 1.1: a Chronology of South Africa's Nuclear Program

A Chronology of South Africa's Nuclear Program by Zondi Masiza Zondi Masiza is a research assistant at the Program for Nonproliferation Studies. He is currently a US AID/Fulbright Scholar at the Monterey Institute for International Studies. Introduction nuclear explosives for the mining industry. The sense of urgency in developing a nuclear capability was sharpened The recent history of South Africa's nuclear program by the southward march of the African liberation presents an important and unprecedented case of a state that movement, which the South African government viewed as developed and then voluntarily relinquished nuclear inspired by the Soviet Union. South Africa conducted its weapons. As we near the 1995 NPT Extension Conference, nuclear weapons program in absolute secrecy. Very few the case of South Africa presents a significant example for government officials and even top Cabinet members knew the declared nuclear powers as well as for those considering of its existence. nuclear deployment. Nuclear weapons may not be the guarantors of regime security that they are purported to be Throughout the 1970s and the 1980s, the Group of 77 by some supporters. Indeed, there may be sound reasons pressured the IAEA to carry out inspections on South why other states in the future may also choose to relinquish African nuclear facilities, such as the pilot uranium them or, in other cases, choose not to develop them at all. enrichment plant. Allegations that South Africa had made preparations to conduct a nuclear test in the Kalahari desert This chronology is based on a survey of publicly-available in 1977 increased concern about the country's intentions.