Fundamentals of the Gestalt Approach to Counselling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy: the Case of Stan and Lecturettes

chapter 8 Gestalt Therapy introduction t 5IF3PMFPG$POGSPOUBUJPO key concepts t (FTUBMU5IFSBQZ*OUFSWFOUJPOT t "QQMJDBUJPOUP(SPVQ$PVOTFMJOH t 7JFXPG)VNBO/BUVSF gestalt therapy from a t 4PNF1SJODJQMFTPG(FTUBMU5IFSBQZ5IFPSZ multicultural perspective t 5IF/PX t 6OmOJTIFE#VTJOFTT t 4USFOHUIT'SPNB%JWFSTJUZ1FSTQFDUJWF t $POUBDUBOE3FTJTUBODFTUP $POUBDU t 4IPSUDPNJOHT'SPNB%JWFSTJUZ1FSTQFDUJWF t &OFSHZ BOE#MPDLTUP&OFSHZ gestalt therapy applied the therapeutic process to the case of stan t 5IFSBQFVUJD(PBMT summary and evaluation t 5IFSBQJTUT'VODUJPOBOE3PMF t 4VNNBSZ t $MJFOUT&YQFSJFODFJO5IFSBQZ t $POUSJCVUJPOTPG(FTUBMU5IFSBQZ t 3FMBUJPOTIJQ#FUXFFO5IFSBQJTUBOE$MJFOU5IFS t -JNJUBUJPOTBOE$SJUJDJTNTPG(FTUBMU5IFSBQZ application: therapeutictherape where to go from here techniques and proceduresproc t 3FDPNNFOEFE4VQQMFNFOUBSZ3FBEJOHT tt 5IF&YQFSJNFOUJO(FTUBMU5IFSBQZ5 IF &YQFSJNFO t 3FGFSFODFTBOE4VHHFTUFE3FBEJOHT tt 1SFQBSJO1SFQBSJOH$MJFOUTGPS(FTUBMU&YQFSJNFOUT$MJFOUT GPS (FTUBMU &Y 210 Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. Fritz Perls / LAURA PERLS FREDERICK S. (“FRITZ”) PERLS, MD, PhD Perls and several of his colleagues established (1893–1970), was the main originator and devel- the New York Institute for Gestalt Therapy in 1952. oper of Gestalt therapy. Born in Berlin, Germany, Eventually Fritz left New York and settled in Big into a lower-middle-class Jewish family, he later Sur, California, where he conducted workshops and identified himself as a source of much trouble for seminars at the Esalen Institute, carving out his his parents. -

The Self, the ®Eld and the Either-Or

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPHY, VOL. 5, NO. 3, 2000 219 The self, the ® eld and the either-or JOHN ROWAN 70 Kings Head Hill, North Chingford, London N4 7LY, UK Abstract It has become fashionable both in psychoanalytic and in humanistic circles to talk about dialogue, the interpersonal ® eld, language and the socially constructed self, and to say that the old idea of the self as central, as real, as essence, is outdated and even patriarchal. But there is something strange about this. In discovering the ® eld (which perhaps we could liken to the wave function in physics) and in denying the individual (which perhaps we could liken to the particle) many people seem to be denying or ignoring the principle of complementarity. The whole point about the authentic self is that it can relate authentically. I see no contradiction between saying that and saying that authentic selves in relation form a ® eld, which has to be respected in its own right. Ken Wilber uses the idea (taken from Arthur Koestler) of a holon. A holon is a unit which is also a part of other units. Holons as a whole form a ® eld, within which are numbers of sub-® elds. In this way we can see how a holon can be regarded at one and the same time as a separable unit and as part of a larger ® eld. There is nothing dif® cult about this. We don’t have to give up one in order to have the other. It has become fashionable to talk about dialogue, the interpersonal ® eld, language and the socially constructed self. -

Pioneering Cultural Initiatives by Esalen Centers for Theory

Esalen’s Half-Century of Pioneering Cultural Initiatives 1962 to 2012 For more information, please contact: Jane Hartford, Director of Development Center for Theory & Research and Special Projects Special Assistant to the Cofounder and Chairman Emeritus Michael Murphy Esalen Institute 1001 Bridgeway #247 Sausalito, CA 94965 415-459-5438 i Preface Most of us know Esalen mainly through public workshops advertised in the catalog. But there is another, usually quieter, Esalen that’s by invitation only: the hundreds of private initiatives sponsored now by Esalen’s Center for Theory and Research (CTR). Though not well publicized, this other Esalen has had a major impact on America and the world at large. From its programs in citizen diplomacy to its pioneering role in holistic health; from physics and philosophy to psychology, education and religion, Esalen has exercised a significant influence on our culture and society. CTR sponsors work in fields that think tanks and universities typically ignore, either because those fields are too controversial, too new, or because they fall between disciplinary silos. These initiatives have included diplomats and political leaders, such as Joseph Montville, the influential pioneer of citizen diplomacy, Jack Matlock and Arthur Hartman, former Ambassadors to the Soviet Union, and Claiborne Pell, former Chairman of the U.S. Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee; eminent Russian cultural leaders Vladimir Pozner, Sergei Kapitsa, and Victor Erofeyev; astronaut Rusty Schweickart; philosophers Jay Ogilvy, Sam -

The Historical Roots of Gestalt Therapy Theory

The Historical Roots of Gestalt Therapy Theory Rosemarie Wulf The theory of Gestalt therapy is itself a new Gestalt, though it does not contain many new thoughts. What its founders, Fritz and Laura Perls and Paul Goodman, did was to weave a new synthesis out of existing concepts. The background of this new Gestalt is composed of concepts and elements from different bodies of knowledge and disciplines. I would like to give you an idea of the cultural and historical situation that is the Zeitgeist (the spirit of the time) that prevailed during the lifetimes of the founders of Gestalt therapy. What kind of theories and traditions did Fritz and Laura come into contact with? Where did they find ideas that were in line with their own, what other ideas did they reject in their search for answers to the fundamental questions that are either implicitly or explicitly contained in every theory of psychotherapy? What is a human being? How does he or she function? Why do we exist? Is there a reason to exist? How should we behave toward each other? How does psychological illness develop? Firstly the background: the wider field, an overview of the Zeitgeist. In the second part, I will present the various contacts Fritz and Laura Perls had with specific persons and their ideas or theoretical models. The beginning of the 20th century was characterized by an explosive development of science and technology. The era of automation and cybernetics had begun. The rise of nuclear and quantum physics led to radical revolutionary change. Biology, chemistry and medicine also began to make rapid progress. -

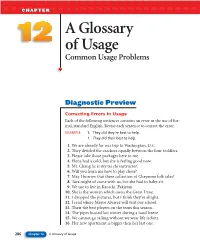

A Glossary of Usage Common Usage Problems

NL_EOL_SE07_P1_C12_286-305.qxd 4/18/07 2:57 PM Page 286 CHAPTER A Glossary of Usage Common Usage Problems Diagnostic Preview Correcting Errors in Usage Each of the following sentences contains an error in the use of for- mal, standard English. Revise each sentence to correct the error. EXAMPLE 1. They did they’re best to help. 1. They did their best to help. 1. We are already for our trip to Washington, D.C. 2. They divided the crackers equally between the four toddlers. 3. Please take those packages here to me. 4. Elena had a cold, but she is feeling good now. 5. Mr. Chang he is my tai chi instructor. 6. Will you learn me how to play chess? 7. May I borrow that there collection of Cheyenne folk tales? 8. Tara might of come with us, but she had to baby-sit. 9. We use to live in Karachi, Pakistan. 10. She is the woman which owns the Great Dane. 11. I dropped the pictures, but I think they’re alright. 12. I read where Mayor Alvarez will visit our school. 13. Their the best players on the team this season. 14. The pipes busted last winter during a hard freeze. 15. We cannot go sailing without we wear life jackets. 16. Her new apartment is bigger then her last one. 286 Chapter 12 A Glossary of Usage NL_EOL_SE07_P1_C12_286-305.qxd 4/18/07 2:57 PM Page 287 17. The group went everywheres together. 18. Lydia acted like she was bored. 19. Antonyms are when words are opposite in meaning. -

Towards a More Deeply Embodied Approach in Gestalt Therapy 1

Studies in Gestalt Therapy 2(2), 43-56 James I. Kepner Towards a More Deeply Embodied Approach in Gestalt Therapy 1 This article critiques and assesses the development of body-oriented work in gestalt therapy. Strengths of the gestalt therapy approach are highlighted as work with the "actual," and holding an integral viewpoint. The author criti ques limitations in the field involving a narrow epistemology of the founding perspective, the inadequacy of awareness alone for psychophysical change, the inclusion of structural concepts, and the need for physical methodology including touch and movement and other somatic methods. A brief model is offered for appreciating the multi-level complexity of a more fully embodied approach. Key words: Body-oriented work, gestalt therapy, epistemology, gestalt therapy training, non-dualistic approach, self, organism/ environment field, figure/ ground, structured ground, awareness, patterns and organization, developmental theory. Borfy Process: A Gestalt Approach to Working With the Borfy in P.rychotherapy (Kepner, 1987) was published 21 years ago. The book was my attempt to articulate a fuller body-oriented psychotherapy from the gestalt therapy ap proach. Gestalt therapy certainly had interest in body process and experience but, up to that time, the actual methodology for body-oriented practice was very limited. I found the ways in which gestalt therapists utilized more inten sive body therapeutic techniques to be a kind of grafting of often incompati ble methods or approaches onto gestalt therapy technique. This often re sulted in an unintegrated hodge-podge. As a "Young Turk" at the brash age of 34, I also had the motivation to "correct" my elders and teachers in the gestalt therapy world who, I thought, did not go far enough in working with the body. -

Ericksonian Hypnosis and the Enneagram About Neurolinguistic Programming (NLP)

The Changeworks Consulting, Training, Books and CDs Workshops with Thomas Condon PO Box 5909, Bend, OR 97708 001-541-382-1894 email: [email protected] http://www.thechangeworks.com Ericksonian Hypnosis and the Enneagram About Neurolinguistic Programming (NLP) NLP is a set of distinctions and techniques for altering the structure of subjective experience. Created in the 1970’s by Richard Bandler and John Grinder, NLP is based in linguistics, psychology and communication. Among other things it offers a model of good communication and good rapport. It has had extensive applications in the fields of business, education, training and health, as well as in therapeutic changework. NLP is based upon the premise that experience has structure, and that by altering the structure, you can alter the experience. NLP helps you analyze how you create your subjective experience through your senses. At any given moment, your internal experience has a visual part - what you see around you or in your mind’s eye; an auditory part - hearing the sounds in your environment or listening to internal voices; and a kinesthetic part - your emotions and body feelings. As you experience the world through your five senses, you interpret the information and then act on it. In broad strokes, NLP helps you recognize your primary sensory modality – whether you are generally visual or auditory or kinesthetic or favor a combination of those primary senses. Nobody is really purely auditory, visual or kinesthetic, but you might find that you have a favorite orientation. Once you’ve determined your existing sensory bias, NLP offers techniques to expand your experience of your other senses. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Benefits, Limitations, and Potential Harm in Psychodrama

Benefits, Limitations, and Potential Harm in Psychodrama (Training) © Copyright 2005, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2016 Rob Pramann, PhD, ABPP (Group Psychology) CCCU Training in Psychodrama, Sociometry, and Group Psychotherapy This article began in 2005 in response to a new question posed by the Utah chapter of NASW on their application for CEU endorsement. “If any speaker or session is presenting a fairly new, non-traditional or alternative approach, please describe the limitations, risks and/or benefits of the methods taught.” After documenting how Psychodrama is not a fairly new, non-traditional or alternative approach I wrote the following. I have made minor updates to it several times since. As a result of the encouragement, endorsement, and submission of it by a colleague it is listed in the online bibliography of psychodrama http://pdbib.org/. It is relevant to my approach to the education/training/supervision of Group Psychologists and the delivery of Group Psychology services. It is not a surprise that questions would be raised about the benefits, limitations, and potential harm of Psychodrama. J.L. Moreno (1989 – 1974) first conducted a psychodramatic session on April 1, 1921. It was but the next step in the evolution of his philosophical and theological interests. His approach continued to evolve during his lifetime. To him, creativity and (responsible) spontaneity were central. He never wrote a systematic overview of his approach and often mixed autobiographical and poetic material in with his discussion of his approach. He was a colorful figure and not afraid of controversy (Blatner, 2000). He was a prolific writer and seminal thinker. -

You and I Some Puzzles About ‘Mutual Recognition’

You and I Some puzzles about ‘mutual recognition’ Michael Thompson University of Pittsburgh Slide 0 Predicating “ξ has a bruised nose” in speech NOMINALLY: “Hannah has a bruised nose” DEMONSTRATIVELY: “This girl has a bruised nose” FIRST PERSONALLY: “I have a bruised nose” Slide 1 Where these are made true by the same bruised nose, the first might be said by anyone, the second by anyone present, and the third by the injured party herself, Hannah. In particular, if Hannah is given to her own senses – in a mirror, for example – she herself might employ any of these three forms of predication. The inner basis of outward speech Outward Speech Hannah said “Hannah has a bruised nose” Hannah said “This girl has bruised nose” Hannah said “I have a bruised nose” Belief Knowlege Hannah believed she had a bruised nose Hannah knew that she had a bruised nose Hannah believed she had a bruised nose Hannah knew that she had a bruised nose Hannah believed she had a bruised nose Hannah knew that she had a bruised nose Slide 2 When Hannah does employ one of these sentences, she is not just saying words, but saying something,orclaiming something; she is perhaps also expressing a belief; and perhaps also manifesting knowledge and imparting knowledge to her hearers. co But whatever she says, it’s the same bruised nose that’s in question: her own, not Martha’s or Solomon’s. There is, as we might say, just one fact in question, one content available, and it pertains to her. We might thus represent the more intellectual states of affairs as follows. -

I Acknowledge That I Have Read, and Do Hereby Accept the Terms And

I acknowledge that I have read, and do hereby accept the terms and conditions contained in this Online/Mobile Branch Disclosure and the Electronic Statement (eStatement) Consent Agreement. Winnebago Community Credit Union Online/Mobile Branch Disclosure The first time that you enter the Winnebago Community Credit Union’s Online or Mobile Branch using your Personal Identification Number(PIN), will indicate that you have accepted and agreed to electronically receive and comply with Winnebago Community Credit Union’s Online/Mobile Branch Disclosure, which appears below, as amended from time to time. Also at that time you will automatically be enrolled in eStatements and enotices. All terms and conditions applicable to Winnebago Community Credit Union’s Online Branch apply to Mobile Branch services. Web access is required to use our Mobile Branch. Mobile service provider download and usage charges may apply. See service provider’s terms and conditions. This agreement between you and Winnebago Community Credit Union ("we" or "us" or "WCCU") contains the terms, conditions and disclosures for your Online/Mobile Branch. Your Online/Mobile Branch allows you to access your deposit accounts, loans, and lines of credit, and you are subject to the rules and regulations governing the general use of those accounts. You will need to use certain types of computers or personal devices, obtain an internet account, and use compliant browser software to use your Online/Mobile Branch. The installation, maintenance, and operation of those items are your responsibility. We are not responsible for any errors or failures of your computer equipment or internet connection software. Your Online/Mobile Branch can be used at any time, 24 hours a day; however, certain system maintenance or malfunctions may make it unavailable at times. -

Beginning Old English / Carole Hough and John Corbett

© Carole Hough and John Corbett 2007 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Beginning Old Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. English Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this Carole Hough and John Corbett work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2007 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN-13: 978–1–4039–9349–6 hardback ISBN-10: 1–4039–9349–1 hardback ISBN-13: 978–1–4039–9350–2 paperback ISBN-10: 1–4039–9350–5 paperback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.