An Overview of Gujarati Dalit Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Sahitya Akademi Translation Prize 2013

DELHI SAHITYA AKADEMI TRANSLATION PRIZE 2013 August 22, 2014, Guwahati Translation is one area that has been by and large neglected hitherto by the literary community world over and it is time others too emulate the work of the Akademi in this regard and promote translations. For, translations in addition to their role of carrying creative literature beyond known boundaries also act as rebirth of the original creative writings. Also translation, especially of ahitya Akademi’s Translation Prizes for 2013 were poems, supply to other literary traditions crafts, tools presented at a grand ceremony held at Pragyajyoti and rhythms hitherto unknown to them. He cited several SAuditorium, ITA Centre for Performing Arts, examples from Hindi poetry and their transportation Guwahati on August 22, 2014. Sahitya Akademi and into English. Jnanpith Award winner Dr Kedarnath Singh graced the occasion as a Chief Guest and Dr Vishwanath Prasad Sahitya Akademi and Jnanpith Award winner, Dr Tiwari, President, Sahitya Akademi presided over and Kedarnath Singh, in his address, spoke at length about distributed the prizes and cheques to the award winning the role and place of translations in any given literature. translators. He was very happy that the Akademi is recognizing Dr K. Sreenivasarao welcomed the Chief Guest, and celebrating the translators and translations and participants, award winning translators and other also financial incentives are available now a days to the literary connoisseurs who attended the ceremony. He translators. He also enumerated how the translations spoke at length about various efforts and programmes widened the horizons his own life and enriched his of the Akademi to promote literature through India and literary career. -

Kirtan Leelaarth Amrutdhaara

KIRTAN LEELAARTH AMRUTDHAARA INSPIRERS Param Pujya Dharma Dhurandhar 1008 Acharya Shree Koshalendraprasadji Maharaj Ahmedabad Diocese Aksharnivasi Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Hariswaroopdasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Dharmanandandasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) PUBLISHER Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple (Kenton-Harrow) (Affiliated to Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj – Kutch) PUBLISHED 4th May 2008 (Chaitra Vad 14, Samvat 2064) Produced by: Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton Harrow All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. © Copyright 2008 Artwork designed by: SKSS Temple I.T. Centre © Copyright 2008 Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton, Harrow Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple Westfield Lane, Kenton, Harrow Middlesex, HA3 9EA, UK Tel: 020 8909 9899 Fax: 020 8909 9897 www.sksst.org [email protected] Registered Charity Number: 271034 i ii Forword Jay Shree Swaminarayan, The Swaminarayan Sampraday (faith) is supported by its four pillars; Mandir (Temple), Shastra (Holy Books), Acharya (Guru) and Santos (Holy Saints & Devotees). The growth, strength and inter- supportiveness of these four pillars are key to spreading of the Swaminarayan Faith. Lord Shree Swaminarayan has acknowledged these pillars and laid down the key responsibilities for each of the pillars. He instructed his Nand-Santos to write Shastras which helped the devotees to perform devotion (Bhakti), acquire true knowledge (Gnan), practice righteous living (Dharma) and develop non- attachment to every thing material except Supreme God, Lord Shree Swaminarayan (Vairagya). There are nine types of bhakti, of which, Lord Shree Swaminarayan has singled out Kirtan Bhakti as one of the most important and fundamental in our devotion to God. -

Dr Rajendra Mehta.Pdf

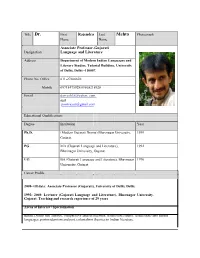

Title Dr. First Rajendra Last Mehta Photograph Name Name Associate Professor-Gujarati Designation Language and Literature Address Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, Tutorial Building, University of Delhi, Delhi -110007. Phone No Office 011-27666626 Mobile 09718475928/09868218928 Email darvesh18@yahoo. com and [email protected] Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. (Modern Gujarati Drama) Bhavnagar University, 1999 Gujarat. PG MA (Gujarati Language and Literature), 1992 Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. UG BA (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar 1990 University, Gujarat. Career Profile 2008- till date: Associate Professor (Gujarati), University of Delhi, Delhi. 1992- 2008: Lecturer (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. Teaching and research experience of 29 years Areas of Interest / Specialization Indian Drama and Theatre, comparative Indian literature, translation studies, translations into Indian languages, postmodernism and post colonialism theories in Indian literature. Subjects Taught 1- Gujarati language courses (certificate, diploma, advanced diploma) 2-M.A (Comparative Indian Literature) Theory of literary influence, Tragedy in Indian literature, Ascetics and poetics 3-M.Phil (Comparative Indian Literature): Gandhi in Indian literature. Introduction to an Indian language- Gujarati Research Guidance M.Phil. student -12 Ph.D. student - 05 Details of the Training Programmes attended: Name of the Programme From Date To Date Duration Organizing Institution -

SAHITYASETU ISSN: 2249-2372 a Peer-Reviewed Literary E-Journal

Included in the UGC Approved List of Journals SAHITYASETU ISSN: 2249-2372 A Peer-Reviewed Literary e-journal Website: http://www.sahityasetu.co.in Year-8, Issue-5, Continuous Issue-47, September-October 2018 Establishment of Good Womanhood: In the Study of Leelavati Jeevankala The research paper attempts to analyze Leelavati’s art of living. Tripathi decided to write this biography to commemorate his elder daughter Leelavati because the book shows Leelavati’s sacrifice, who died of consumption at the age of 21.Moreover the author Vishnu Prasad Trivedi used the epithet “Maharshi” for Tripathi, because he was a philosopher and well informed writer in Gujarati literature. He was well versed in Sanskrit, English and Gujarati languages” (Trivedi 441). He contributed significantly to Gujarati literature. During his lifetime, he wrote poems, novel, drama, biography etc. (Trivedi 48). He has given the great novel Sarasvatichandra, Which runs into 2000 pages and is divided into four parts, which were published in 1887, 1892, 1898 and 1901 respectively. His other notable works include Navalram Nu Kavi Jeevan 1891, Sneh mudra 1898, Madhavram Smarika1900, Leelavati Jeevankala 1905, Dayaram No Akshardeh 1908, Classical Poets of Gujarat 1916. Moreover, he wrote in Samalochak and Sadavastu Vichar. His personal diary Scrap Books also got published after his death (Trivedi 48). He also wrote two Dramas like Sarasvati and Maya and story like Sati chuni. Moreover, He published articles dealing with the subjects pertaining to education and literature (Trivedi Vishnu Prasad 48). His literary repertoire comprises two biographies, Navalramnu Kavijeevan1891 and Leelavati Jeevankala 1905. The biography Navalramnu Kavijeevan focuses on Navalram’s life. -

Proposal for a Gujarati Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Gujarati Root Zone LGR Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel Proposal for a Gujarati Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-03-06 Document version: 3.6 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1 General Information/ Overview/ Abstract The purpose of this document is to give an overview of the proposed Gujarati LGR in the XML format and the rationale behind the design decisions taken. It includes a discussion of relevant features of the script, the communities or languages using it, the process and methodology used and information on the contributors. The formal specification of the LGR can be found in the accompanying XML document: proposal-gujarati-lgr-06mar19-en.xml Labels for testing can be found in the accompanying text document: gujarati-test-labels-06mar19-en.txt 2 Script for which the LGR is proposed ISO 15924 Code: Gujr ISO 15924 Key N°: 320 ISO 15924 English Name: Gujarati Latin transliteration of native script name: gujarâtî Native name of the script: ગજુ રાતી Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR) version: MSR-4 1 Proposal for a Gujarati Root Zone LGR Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel 3 Background on the Script and the Principal Languages Using it1 Gujarati (ગજુ રાતી) [also sometimes written as Gujerati, Gujarathi, Guzratee, Guujaratee, Gujrathi, and Gujerathi2] is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Indian state of Gujarat. It is part of the greater Indo-European language family. It is so named because Gujarati is the language of the Gujjars. Gujarati's origins can be traced back to Old Gujarati (circa 1100– 1500 AD). -

Breath Becoming a Word

BREATH BECOMING A WORD CONTMPORARY GUJARATI POETRY IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION EDITED BY DILEEP JHAVERI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My earnest thanks to GUJARAT SAHITYA AKADEMI for publishing this book and to Harshad Trivedi. With his wholehearted support a dream is fulfilled. Several of these translations have appeared in INDIAN LITERATURE- Sahitya Akademi Delhi MUSEINDIA KRITYA- web journals and elsewhere. Thanks to all of them. Cover page painting by Late Jagdeep Smart with the kind permission of Smt Nita Smart and Rajarshi Smart Dedicated to PROF. K. SATCHIDANANDAN The eminent poet of Malayalam who has continuously inspired other Indian languages while becoming a sanctuary for the survival of Poetry. BREATH BECOMING A WORD It’s more than being in love, boy, though your ringing voice may have flung your dumb mouth thus: learn to forget those fleeting ecstasies. Far other is breath of real singing. An aimless breath. A stirring in the god. A breeze. Rainer Maria Rilke From Sonnets To Orpheus This is to celebrate the breath becoming a word and the joy of word turning into poetry. This is to welcome the lovers of poetry in other languages to participate in the festival of contemporary Gujarati poetry. Besides the poets included in this selection there are many who have contributed to the survival of Gujarati poetry and there are many other poems of the poets in this edition that need to be translated. So this is also an invitation to the friends who are capable to take over and add foliage and florescence to the growing garden of Gujarati poetry. Let more worthy individuals undertake the responsibility to nurture it with their taste and ability. -

Swaminarayan Bliss March 2009

March 2009 Annual Subscription Rs. 60 HONOURING SHASTRIJI MAHARAJ February 2009 In 1949, Atladara, thousands of devotees ho- noured Brahmaswarup Shastriji Maharaj on his 85th birthday by celebrating his Suvarna Tula. The devotees devoutly weighed Shastriji Ma- haraj against sugar crystals and then weighed the sugar crystals against gold. To commemorate the 60th anniversary of this historic occasion, on 2 February 2009, the devotees of Atladara re-enacted it in the pres- ence of Pramukh Swami Maharaj. Weighing scales were set up under the same neem tree (above) where the original celebration took place. On one side a murti of Shastriji Maharaj was placed and on the other side sugar crystals. Devotees dressed in the traditions of that period joyfully hailed the glory of Shastriji Maharaj. Swamishri also participated in the celebration by placing sugar crystals on the scales. Then, on Sunday, 8 February 2009, the occasion was celebrated on the main assembly stage, and again Swamishri, the sadhus and devotees honoured Shastriji Maharaj (inset). March 2009, Vol. 32 No. 3 CONTENTS FIRST WORD 4 Bhagwan Swaminarayan The Vaishnava tradition in Hinduism Personal Magnetism Maharaj’s divine murti... believes that God manifests on earth in four 7 Sanatan Dharma ways: (1) through his avatars (vibhav) in Worshipping the Charanarvind of God times of spiritual darkness, (2) through his Ancient tradition of Sanatan Dharma... properly consecrated murti (archa) in 8 Bhagwan Swaminarayan mandirs, (3) within the hearts of all beings as The Sacred Charanarvind of Shriji Maharaj their inner controller (antaryamin) and (4) in Darshan to paramhansas and devotees... the form of a guru or bona fide sadhu. -

Download Dialog No-21

EDITOR: Akshaya Kumar EDITORIAL BOARD: Pushpinder Syal Shelley Walia Rana Nayar ADVISORY BOARD: ADVISORY BOARD: (Panjab University) Brian U. Adler C.L. Ahuja Georgia State University, USA lshwar Dutt R. J. Ellis Nirmal Mukerji University of Birmingham, UK N.K.Oberoi Harveen Mann Loyola University, USA Ira Pande Howard Wolf M.L. Raina SUNY, Buffalo, USA Kiran Sahni Mina Singh Subscription Fee: Gyan Verma Rs. 250 per issue or $ 25 per issue Note for Contributors Contributors are requested to follow the latest MLA Handbook. Typescripts should be double-spaced. Two hard copies in MS Word along with a soft copy should be sent to Professor Harpreet Pruthi The Chairperson Department of English and Culture Studies Panjab University Chandigarh160014 INDIA E-mail: [email protected] DIALOG is an interdisciplinary journal which publishes scholary articles, reviews, essays, and polemical interventions. CALL for PAPERS DIALOG provides a forum for interdisciplinary research on diverse aspects of culture, society and literature. For its forthcoming issues it invites scholarly papers, research articles and book reviews. The research papers (about 8000 words) devoted to the following areas would merit our attention most: • Popular Culture Indian Writings in English and Translation • Representations of Gender, Caste and Race • Cinema as Text • Theories of Culture • Emerging Forms ofLiterature Published twice a year, the next two issues of Dialog would carry miscellaneous papers. on the above areas. The contributors are requested to send their papers latest by November, 2012. The papers could be sent electronically at [email protected] or directly to The Editor, Dialog, Department of English and Cultural Studies, Chandigarh -160014. -

Rita Kothari.P65

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER PERSPECTIVES IN INDIAN DEVELOPMENT New Series 47 Questions in and of Language Rita Kothari Humanities and Social Sciences Department, Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar, Gujarat Nehru Memorial Museum and Library 2015 NMML Occasional Paper © Rita Kothari, 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of the contents may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the author. This Occasional Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the NMML. The views expressed in this Occasional Paper are those of the author(s) and speakers and do not represent those of the NMML or NMML policy, or NMML staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide support to the NMML Society nor are they endorsed by NMML. Occasional Papers describe research by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. Questions regarding the content of individual Occasional Papers should be directed to the authors. NMML will not be liable for any civil or criminal liability arising out of the statements made herein. Published by Nehru Memorial Museum and Library Teen Murti House New Delhi-110011 e-mail : [email protected] ISBN : 978-93-83650-63-7 Price Rs. 100/-; US $ 10 Page setting & Printed by : A.D. Print Studio, 1749 B/6, Govind Puri Extn. Kalkaji, New Delhi - 110019. E-mail : [email protected] NMML Occasional Paper Questions in and of Language* Rita Kothari Sorathgada sun utri Janjhar re jankaar Dhroojegadaanrakangra Haan re hamedhooje to gad girnaar re… (K. Kothari, 1973: 53) As Sorath stepped out of the fort Not only the hill in the neighbourhood But the walls of Girnar fort trembled By the sweet twinkle of her toe-bells… The verse quoted above is one from the vast repertoire of narrative traditions of the musician community of Langhas. -

In the Service of Sri Radha Krishnachandra ANNUAL REPORT 2012-13

In the service of Sri Radha Krishnachandra ANNUAL REPORT 2012-13 B A N G A L O R E SEVEN PURPOSES OF ISKCON ?To systematically propagate spiritual knowledge to the society at large and to educate all people in the techniques of spiritual life in order to check the imbalance of values in life and to achieve real unity and peace in the world. To propagate a consciousness of Krishna as it is revealed in the Bhagavad-gita and Srimad-Bhagavatam. To bring the members of the Society together with each other and nearer to Krishna, the prime entity, and thus to develop the idea, within the members, and humanity, at large, that each soul is part and parcel of the quality of Godhead (Krishna). To teach and encourage the sankirtana movement of congregational chanting of the holy name of God as revealed in the teachings of Lord Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. To erect for the members, and for the society at large, a holy place of transcendental pastimes, dedicated to the personality of Krishna. To bring the members closer together for the purpose of teaching a simpler and more natural way of life. With a view towards achieving the aforementioned purposes, to publish and distribute periodicals, magazines, books and other writings. HIS DIVINE GRACE A.C. BHAKTIVEDANTA SWAMI PRABHUPADA (Founder-Acharya: International Society for Krishna Consciousness) CONTENTS President’s Message . 4 Srila Prabhupada . 5 Message from Dignitaries . 6 Annual Overview: Sri Radha Krishna Temple . .8 Sri Radha Krishna Temple Pilgrim Center. 9 Sri Radha Krishna Temple Festivals. 11 Dignitaries who received the Lord's Blessings . -

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India Has Witnessed Strong Growth in Past Few Years

Why India /Why Gujarat/ Why Ahmedabad/ Why Joint Care Arthroscopy Center ? Why India ? Medical Tourism in India has witnessed strong growth in past few years. India is emerging as a preferred destination for international patients due to availability of best in class treatment at fraction of a cost compared to treatment cost in US or Europe. Hospitals here have focused its efforts towards being a world-class that exceeds the expectations of its international patients on all counts, be it quality of healthcare or other support services such as travel and stay. Why Gujarat ? With world class health facilities, zero waiting time and most importantly one tenth of medical costs spent in the US or UK, Gujarat is becoming the preferred medical tourist destination and also matching the services available in Delhi, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Gujarat spearheads the Indian march for the “Global Economic Super Power” status with access to all Major Countries like USA, UK, African countries, Australia, China, Japan, Korea and Gulf Countries etc. Gujarat is in the forefront of Health care in the country. Prosperity with Safety and security are distinct features of This state in India. According to a rough estimate, about 1,200 to 1,500 NRI's, NRG's and a small percentage of foreigners come every year for different medical treatments For The state has various advantages and the large NRG population living in the UK and USA is one of the major ones. Out of the 20 million-plus Indians spread across the globe, Gujarati's boasts 6 million, which is around 30 per cent of the total NRI population.