Evidence of Minoan Astronomy and Calendrical Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Demeter and Dionysos: Connections in Literature, Cult and Iconography Kathryn Cook April 2011

Demeter and Dionysos: Connections in Literature, Cult and Iconography Kathryn Cook April 2011 Demeter and Dionysos are two gods among the Greek pantheon who are not often paired up by modern scholars; however, evidence from a number of sources alluding to myth, cult and iconography shows that there are similarities and connections observable from our present point of view, that were commented upon by contemporary authors. This paper attempts to examine the similarities and connections between Demeter and Dionysos up through the Classical period. These two deities were not always entwined in myth. Early evidence of gods in the Linear B tablets mention Dionysos as the name of a deity, but Demeter’s name does not appear in the records until later. Over the centuries (up to approximately the 6th century as mentioned in this paper), Demeter and Dionysos seem to have been depicted together in cult and in literature more and more often. In particular, the figure of Iacchos in the Eleusinian cult seems to form a bridging element between the two which grew from being a personification of the procession for Demeter, into being a Dionysos figure who participated in her cult. Literature: Demeter and Dionysos have some interesting parallels in literature. To begin with, they are both rarely mentioned in the Homeric poems, compared to other gods like Hera or Athena. In the Iliad, neither Demeter nor Dionysos plays a role as a main character. Instead they are mentioned in passing, as an example or as an element of an epic simile.1 These two divine figures are present even less often in the Odyssey, though this is perhaps a reflection of the fewer appearances of the gods overall, they are 1 Demeter: 2.696. -

The Gulf of Messara Underwater Survey NEH Collaborat

Maritime Landscapes of Southern Crete from the Paleolithic to Modern Times: The Gulf of Messara Underwater Survey NEH Collaborative Research Grant Proposal November 2017 Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World Institute of Nautical Archaeology Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities Karl Krusell Brown University STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE AND IMPACT Maritime Landscapes of Southern Crete from the Paleolithic to Modern Times: The Gulf of Messara Underwater Survey This proposal seeks to gain funding for a major three-year collaborative research project aimed at characterizing the maritime landscapes of southern Crete from the island’s earliest human presence to the expulsion of the Ottomans at the very end of the 19th century CE. The maritime significance of Crete was already established in Greek oral tradition by the time the Iliad and Odyssey were first written down sometime in the 8th century BCE. Clues about the island’s seafaring history derived from such sources as Bronze Age wall paintings and New Testament scripture have provided the basis for much scholarly speculation, but ultimately leave many questions about the long-term development of maritime culture on the island unanswered. A recent debate among Mediterranean archaeologists was prompted by the discovery of lithic artifacts in southern Crete dated to the Paleolithic, which have the potential to push back the earliest human presence on Crete, as well as the earliest demonstrable hominin sea-crossings in the Mediterranean, to around 130,000 years ago. The project team will conduct an underwater survey of the Gulf of Messara, collecting data through both diver reconnaissance and remote sensing in order to ascertain the long-term history of social complexity, resource exploitation, and island connectivity. -

Minoan Religion

MINOAN RELIGION Ritual, Image, and Symbol NANNO MARINATOS MINOAN RELIGION STUDIES IN COMPARATIVE RELIGION Frederick M. Denny, Editor The Holy Book in Comparative Perspective Arjuna in the Mahabharata: Edited by Frederick M. Denny and Where Krishna Is, There Is Victory Rodney L. Taylor By Ruth Cecily Katz Dr. Strangegod: Ethics, Wealth, and Salvation: On the Symbolic Meaning of Nuclear Weapons A Study in Buddhist Social Ethics By Ira Chernus Edited by Russell F. Sizemore and Donald K. Swearer Native American Religious Action: A Performance Approach to Religion By Ritual Criticism: Sam Gill Case Studies in Its Practice, Essays on Its Theory By Ronald L. Grimes The Confucian Way of Contemplation: Okada Takehiko and the Tradition of The Dragons of Tiananmen: Quiet-Sitting Beijing as a Sacred City By By Rodney L. Taylor Jeffrey F. Meyer Human Rights and the Conflict of Cultures: The Other Sides of Paradise: Western and Islamic Perspectives Explorations into the Religious Meanings on Religious Liberty of Domestic Space in Islam By David Little, John Kelsay, By Juan Eduardo Campo and Abdulaziz A. Sachedina Sacred Masks: Deceptions and Revelations By Henry Pernet The Munshidin of Egypt: Their World and Their Song The Third Disestablishment: By Earle H. Waugh Regional Difference in Religion and Personal Autonomy 77u' Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: By Phillip E. Hammond Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response Minoan Religion: Ritual, Image, and Symbol By By George D. Bond Nanno Marinatos A History of the Jews of Arabia: From Ancient Times to Their Eclipse Under Islam By Gordon Darnell Newby MINOAN RELIGION Ritual, Image, and Symbol NANNO MARINATOS University of South Carolina Press Copyright © 1993 University of South Carolina Published in Columbia, South Carolina, by the University of South Carolina Press Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Marinatos, Nanno. -

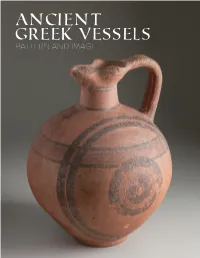

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

Ekaterina Avaliani (Tbilisi) *

Phasis 2-3, 2000 Ekaterina Avaliani (Tbilisi) ORIGINS OF THE GREEK RELIGION: MINOAN AND MYCENAEAN CULTURAL CONVERGENCE Natw"ally, the convergence of Minoan and Mycenaean ethno-cultures would cause certain changes in religious consciousness. The metamorphosis in religion and mentality are hard to explain from the present perspective. During this process, the orientation of Minoan religion might have totally changed (the "victorious gods" of Achaeans might have eclipsed the older ones ofMinoans).1 On the other hand, the evidence of religious syncretism should by no means be ignored. Thus, based on the materials avail able, we may lead our investigation in the following directions: I. While identifying Minoan religious concepts and cults, we should operate with: a) scenes depicted on a11ifacts; b) antique written sources and mythopoetics, which have preserved certain information on Minoan religious concepts and rituals.2 2. To identify gods of the Mycenaean period, we use linear B texts and artifacts. It is evident that the Mycenaean period has the group of gods that are directly related to Minoan world, and on the other hand, the group of gods that is unknown to pre-Hellenic religious tradition. And, finally, 3.We identify another group of gods that reveal their syncretic nature already in the Mycenaean period. * * * Minoan cult rituals were tightly linked to nature. Cave dwellings, mountains and grottos were the charismatic spaces where the rituals were held.3 One of such grottos near Candia was related to the name of Minoan goddess Eileithyia.4 Homer also mentions Eileithyia. The goddess was believed to protect pregnant women and women in childbirth.5 Also, there might have been another sacred place, the top of a hill - Dikte, which was associated with Minoan goddess Diktunna (Dikte - "Sacred Mountain").6 Later in Greek mythology, the goddess assimilated to Artemis ("huntress") (Solinus II . -

Kretan Cult and Customs, Especially in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods: a Religious, Social, and Political Study

i Kretan cult and customs, especially in the Classical and Hellenistic periods: a religious, social, and political study Thesis submitted for degree of MPhil Carolyn Schofield University College London ii Declaration I, Carolyn Schofield, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been acknowledged in the thesis. iii Abstract Ancient Krete perceived itself, and was perceived from outside, as rather different from the rest of Greece, particularly with respect to religion, social structure, and laws. The purpose of the thesis is to explore the bases for these perceptions and their accuracy. Krete’s self-perception is examined in the light of the account of Diodoros Siculus (Book 5, 64-80, allegedly based on Kretan sources), backed up by inscriptions and archaeology, while outside perceptions are derived mainly from other literary sources, including, inter alia, Homer, Strabo, Plato and Aristotle, Herodotos and Polybios; in both cases making reference also to the fragments and testimonia of ancient historians of Krete. While the main cult-epithets of Zeus on Krete – Diktaios, associated with pre-Greek inhabitants of eastern Krete, Idatas, associated with Dorian settlers, and Kretagenes, the symbol of the Hellenistic koinon - are almost unique to the island, those of Apollo are not, but there is good reason to believe that both Delphinios and Pythios originated on Krete, and evidence too that the Eleusinian Mysteries and Orphic and Dionysiac rites had much in common with early Kretan practice. The early institutionalization of pederasty, and the abduction of boys described by Ephoros, are unique to Krete, but the latter is distinct from rites of initiation to manhood, which continued later on Krete than elsewhere, and were associated with different gods. -

Daimonic Imagination

Daimonic Imagination Daimonic Imagination: Uncanny Intelligence Edited by Angela Voss and William Rowlandson Daimonic Imagination: Uncanny Intelligence, Edited by Angela Voss and William Rowlandson This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Angela Voss and William Rowlandson and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4726-7, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4726-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Daimonic History Chapter One ................................................................................................. 8 When Spirit Possession is Sexual Encounter: The Case for a Cult of Divine Birth in Ancient Greece Marguerite Rigoglioso Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 23 Encounters at the Tomb: Visualizing the Invisible in Attic Vase Painting Diana Rodríguez Pérez Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

1 Mystery Cults and Visual Language in Graeco-Roman Antiquity: an Introduction

1 Mystery Cults and Visual Language in Graeco-Roman Antiquity: An Introduction Nicole Belayche and Francesco Massa Like the attendants at the rites, who stand outside at the doors […] but never pass within. Dio Chrysostomus … Behold, I have related things about which you must remain in igno- rance, though you have heard them. Apuleius1 ∵ These two passages from two authors, one writing in Greek, the other in Latin, set the stage of this book on Mystery cults in Visual Representation in Graeco-Roman Antiquity. In this introductory chapter we begin with a broad and problematiz- ing overview of mystery cults, stressing the original features of “mysteries” in the Graeco-Roman world – as is to be expected in this collection, and as is necessary when dealing with this complex phenomenon. Thereafter we will address our specific question: the visual language surrounding the mysteries. It is a complex and daunting challenge to search for ancient mysteries,2 whether represented textually or visually, whether we are interested in their 1 Dio Chrysostomus, Discourses, 36, 33: ὅμοιον εἶναι τοῖς ἔξω περὶ θύρας ὑπηρέταις τῶν τελετῶν […] οὐδέ ποτ’ ἔνδον παριοῦσιν (transl. LCL slightly modified); Apuleius, Metamorphoses, 11, 23: Ecce tibi rettuli, quae, quamvis audita, ignores tamen necesse est (transl. J. Gwyn Griffiths, Apuleius of Madauros, The Isis-Book (Metamorphoses, book XI) (Leiden, Brill: 1975), 99). 2 Thus the program (2014–2018) developed at the research center AnHiMA (UMR 8210, Paris) on “Mystery Cults and their Specific Ritual Agents”, in collaboration with the programs “Ambizione” and “Eccellenza”, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and hosted by the University of Geneva (2015–2018) and University of Fribourg (2019–2023). -

Sacred Union

SACRED UNION Awakening to the Consciousness of Eden Also by Tanishka The Inner Goddess Makeover Sacred Union: Awakening to the Consciousness of Eden, Volume One: Creating Sacred Union Within Coming Soon Sacred Union: Awakening to the Consciousness of Eden, Volume Three: Creating Sacred Union in Community SACRED UNION Awakening to the Consciousness of Eden By TANISHKA Volume Two: Red Tantra Creating Sacred Union in Partnership Copyright © 2014 by Tanishka All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic or electronic process, or in the form of a phonographic recording; nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise copied for public or private use—other than 'fair use' as brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews— without the prior written permission of the publisher. The intent of the author is only to offer information of a general nature to assist in personal growth and self-awareness. In the event you use any of the information contained within this book, as is your legal right, no responsibility will be assumed by the publisher for your actions. First Printing: 2014 ISBN: 978-0-9874263-3-8 Published by Star of Ishtar Publishing P.O. Box 101, Olinda VIC 3788 Australia www.starofishtar.com Dedication To those who are dedicated to restoring the sacred balance of opposites here on Earth. Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Christ, the Magdalene, Ishtar, Gaia, Luna and Sol for pouring their teachings through me as a channel, as well as their patience and faith in me to birth this book. -

Contacts: Crete, Egypt, and the Near East Circa 2000 B.C

Malcolm H. Wiener major Akkadian site at Tell Leilan and many of its neighboring sites were abandoned ca. 2200 B.C.7 Many other Syrian sites were abandoned early in Early Bronze (EB) IVB, with the final wave of destruction and aban- donment coming at the end of EB IVB, Contacts: Crete, Egypt, about the end of the third millennium B.c. 8 In Canaan there was a precipitous decline in the number of inhabited sites in EB III— and the Near East circa IVB,9 including a hiatus posited at Ugarit. In Cyprus, the Philia phase of the Early 2000 B.C. Bronze Age, "characterised by a uniformity of material culture indicating close connec- tions between different parts of the island"10 and linked to a broader eastern Mediterra- This essay examines the interaction between nean interaction sphere, broke down, per- Minoan Crete, Egypt, the Levant, and Ana- haps because of a general collapse of tolia in the twenty-first and twentieth cen- overseas systems and a reduced demand for turies B.c. and briefly thereafter.' Cypriot copper." With respect to Egypt, Of course contacts began much earlier. Donald Redford states that "[t]he incidence The appearance en masse of pottery of Ana- of famine increases in the late 6th Dynasty tolian derivation in Crete at the beginning and early First Intermediate Period, and a of Early Minoan (EM) I, around 3000 B.C.,2 reduction in rainfall and the annual flooding together with some evidence of destructions of the Nile seems to have afflicted northeast and the occupation of refuge sites at the time, Africa with progressive desiccation as the suggests the arrival of settlers from Anatolia. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

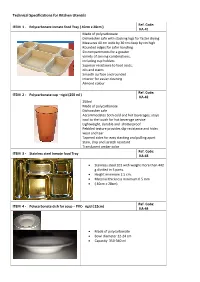

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils Ref. Code: ITEM 1 - Polycarbonate inmate food Tray ( 40cm x 28cm ) KA-41 Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe with stacking lugs for faster drying Measures 40 cm wide by 30 cm deep by cm high Rounded edges for safer handling Six compartments for a greater variety of serving combinations, including cup holders Superior resistance to food acids, oils and stains Smooth surface and rounded interior for easier cleaning Almond colour Ref. Code: ITEM 2 - Polycarbonate cup –rigid (250 ml ) KA-42 250ml Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe Accommodates both cold and hot beverages; stays cool to the touch for hot beverage service Lightweight, durable and shatterproof Pebbled texture provides slip-resistance and hides wear and tear Tapered sides for easy stacking and pulling apart Stain, chip and scratch resistant Translucent amber color Ref. Code: ITEM 3 - Stainless steel Inmate food Tray KA-43 • Stainless steel 201 with weight more than 442 g divided in 5 parts. • Height minimum 2.5 cm. • Material thickness minimum 0.5 mm • ( 40cm x 28cm) Ref. Code: ITEM 4 - Polycarbonate dish for soup – PVC- rigid ( 22cm) KA-44 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 350-360 ml Ref. Code: ITEM 5 - Plastic dish for salad – PVC- rigid KA-45 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 225-250 ml ITEM 6- Heavy Duty Frying-pan from ( 2 set of 6 pcs from the biggest until Ref. Code: the smallest size) KA-46 Set of 6 Pcs from the biggest until the smallest size) Size fir the biggest one : 30-035 x 15-19.0-15 x 2.5 6.0 • Weight: 0.6-1.5 kg • Material: stainless steel Ref.