A Critical Inquiry Into Phoolan Devi's Subaltern Voice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc Vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P

Supreme Court of India Bobby Art International, Etc vs Om Pal Singh Hoon & Ors on 1 May, 1996 Author: Bharucha Bench: Cji, S.P. Bharucha, B.N. Kirpal PETITIONER: BOBBY ART INTERNATIONAL, ETC. Vs. RESPONDENT: OM PAL SINGH HOON & ORS. DATE OF JUDGMENT: 01/05/1996 BENCH: CJI, S.P. BHARUCHA , B.N. KIRPAL ACT: HEADNOTE: JUDGMENT: WITH CIVIL APPEAL NOS. 7523, 7525-27 AND 7524 (Arising out of SLP(Civil) No. 8211/96, SLP(Civil) No. 10519-21/96 (CC No. 1828-1830/96 & SLP(C) No. 9363/96) J U D G M E N T BHARUCHA, J. Special leave granted. These appeals impugn the judgment and order of a Division Bench of the High Court of Delhi in Letters Patent appeals. The Letters Patent appeals challenged the judgment and order of a learned single judge allowing a writ petition. The Letters Patent appeals were dismissed, subject to a direction to the Union of India (the second respondent). The writ petition was filed by the first respondent to quash the certificate of exhibition awarded to the film "Bandit Queen" and to restrain its exhibition in India. The film deals with the life of Phoolan Devi. It is based upon a true story. Still a child, Phoolan Devi was married off to a man old enough to be her father. She was beaten and raped by him. She was tormented by the boys of the village; and beaten by them when she foiled the advances of one of them. A village panchayat called after the incident blamed Phoolan Devi for attempting to entice the boy, who belonged to a higher caste. -

“Low” Caste Women in India

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 735-745 Research Article Jyoti Atwal* Embodiment of Untouchability: Cinematic Representations of the “Low” Caste Women in India https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0066 Received May 3, 2018; accepted December 7, 2018 Abstract: Ironically, feudal relations and embedded caste based gender exploitation remained intact in a free and democratic India in the post-1947 period. I argue that subaltern is not a static category in India. This article takes up three different kinds of genre/representations of “low” caste women in Indian cinema to underline the significance of evolving new methodologies to understand Black (“low” caste) feminism in India. In terms of national significance, Acchyut Kanya represents the ambitious liberal reformist State that saw its culmination in the constitution of India where inclusion and equality were promised to all. The movie Ankur represents the failure of the state to live up to the postcolonial promise of equality and development for all. The third movie, Bandit Queen represents feminine anger of the violated body of a “low” caste woman in rural India. From a dacoit, Phoolan transforms into a constitutionalist to speak about social justice. This indicates faith in Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s India and in the struggle for legal rights rather than armed insurrection. The main challenge of writing “low” caste women’s histories is that in the Indian feminist circles, the discourse slides into salvaging the pain rather than exploring and studying anger. Keywords: Indian cinema, “low” caste feminism, Bandit Queen, Black feminism By the late nineteenth century due to certain legal and socio-religious reforms,1 space of the Indian family had been opened to public scrutiny. -

British Black Power

SOR0010.1177/0038026119845550The Sociological ReviewNarayan 845550research-article2019 The Sociological Article Review The Sociological Review 2019, Vol. 67(5) 945 –967 British Black Power: © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: The anti-imperialism of sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119845550 10.1177/0038026119845550 political blackness and the journals.sagepub.com/home/sor problem of nativist socialism John Narayan School of Social Sciences, Birmingham City University, UK Abstract The history of the US Black Power movement and its constituent groups such as the Black Panther Party has recently gone through a process of historical reappraisal, which challenges the characterization of Black Power as the violent, misogynist and negative counterpart to the Civil Rights movement. Indeed, scholars have furthered interest in the global aspects of the movement, highlighting how Black Power was adopted in contexts as diverse as India, Israel and Polynesia. This article highlights that Britain also possessed its own distinctive form of Black Power movement, which whilst inspired and informed by its US counterpart, was also rooted in anti-colonial politics, New Commonwealth immigration and the onset of decolonization. Existing sociological narratives usually locate the prominence and visibility of British Black Power and its activism, which lasted through the 1960s to the early 1970s, within the broad history of UK race relations and the movement from anti-racism to multiculturalism. However, this characterization neglects how such Black activism conjoined explanations of domestic racism with issues of imperialism and global inequality. Through recovering this history, the article seeks to bring to the fore a forgotten part of British history and also examines how the history of British Black Power offers valuable lessons about how the politics of anti-racism and anti-imperialism should be united in the 21st century. -

The Hunt for Phoolan Devi

• COVER STORY THE HUNT FOR \ • .\-~ !PHOOLAN '--------I OEVI On theafternoonof31 March, when on an informer'a' rrp-Off the police surrounded Gulauli village in UP)j' Jalaun district, they thought they would finally, get the dacoit queen Phoolan Devi; but she slipped awa;}!. Nirmal Mitra visited Gulauli to report on the massive hunt, and the ~~~ .. encounte~ j.n.which most of Phoolan's gang was wiped out. ~ hoolan Devi. the dacoit PhoOian Devi had been arrested and queen. is a desperate was being brought 10 UP's capital by ~ ~\ woman loday, fun ninA for helicopter; it was later discovered to her life. The whole police be an A.pril Fool's joke. Even the news force of Unar Pradesh agencies had been taken in by this se~msP to be after her; she is every.- prank.) one's prize catcli. More than half of The manner in which Phoolan Devi her small gang has already been wiped escaped from the police on 31 March out in one encounter with the police makes an ahsolutely fascinating story. after another during this war that the typical of all that has come to be police have launched on dacoits after associated with dacoits-violence. wit. the bloody revenge that Phoolan Devi presence of mind, and that important took on the Behmai rhaJcurs (see Sun- mgredient, a sense of honour. It seems day 15 March) who had once insulted straight tiut of a Bombay film. and humiliated her. Other important Raba Mustaqim (he was a Muslim) dacoit leaders are angry':with her; by was killed on 4 March near Akbarpur this one outrage. -

La Regina Dei Banditi.Rtf

EDIZIONE SPECIALE In occasione del IV° Festival Internazionale della Letteratura Resistente Pitigliano - Elmo di Sorano, 8 - 9 - 10 settembre 2006 La Regina dei banditi uno spettacolo di Mutamenti Compagnia Laboratorio MILLELIRE STAMPA ALTERNATIVA con Sara Donzelli Direzione editoriale Marcello Baraghini regia Giorgio Zorcù drammaturgia Federico Bertozzi produzione Accademia Amiata Mutamenti Accademia Amiata Mutamenti Toscana delle Culture 58031 Arcidosso (Gr) tel. 348 4036571 [email protected] Grafica di copertina C&P Adver 3 Le pareti della casa erano spalmate di fango, il tet- to era di paglia. All’interno tre stanze affacciate su un cortiletto. Una per dormire, una per cucinare e una per le mucche. Nessuna finestra, vivevano al buio. Di rado, una scatola di latta con lo stoppino diventava una lampada; olio non ce n’era: costava troppo. A parte tre stuoie nella stanza della notte e una sulla soglia di quella delle mucche, l’unico arre- damento della casa era un tempietto votivo. Nella stagione calda dormivano all’aperto. Le mucche dormivano sempre al chiuso per paura dei ladri. E- rano poveri mallah: possedevano solo i regali del fiume. Alla piccola Phoolan piaceva l’odore della terra bagnata. Ne raccoglieva manciate e le masticava: era un sapore inebriante. Di manghi e lenticchie ne mangiavano pochi. Di giorno, durante il lavoro nei 5 campi, si nutrivano con piselli salati, di sera solo pa- tate. Mentre la veglia si alternava al sonno e il lavo- ro al poco riposo, la fame era continua. Come il re- spiro. Un giorno Phoolan fu convocata dal Pradham, uomo importante, capo di tutti i villaggi del distret- to, perché gli togliesse i pidocchi. -

Black Oppressed People All Over the World Are One’: the British Black Panthers’ Grassroots Internationalism, 19691973

`Black oppressed people all over the world are one': the British Black Panthers' grassroots internationalism, 1969-1973 Article (Accepted Version) Angelo, Anne-Marie (2018) ‘Black oppressed people all over the world are one’: the British Black Panthers’ grassroots internationalism, 1969-1973. Journal of Civil and Human Rights, 4 (1). pp. 64-97. ISSN 2378-4245 This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/65918/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk ‘Black Oppressed People All Over the World Are One’: The British Black Panthers’ Grassroots Internationalism, 1969-1973 Anne-Marie Angelo University of Sussex Under review with The Journal of Civil and Human Rights August 2016 On March 21, 1971, over 4,500 people opposing a proposed UK government Immigration Bill marched from Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park, London to Whitehall. -

British Black Power: the Anti-Imperialism of Political Blackness and the Problem of Nativist Socialism

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1177/0038026119845550 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Narayan, J. (2019). British Black Power: The anti-imperialism of political blackness and the problem of nativist socialism . SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW, 67(5), 845-967. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026119845550 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Subalterns: a Comparative Study of African American and Dalit/Indian Literatures

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 5-31-2010 "Speaking" Subalterns: A Comparative Study of African American and Dalit/Indian Literatures Mantra Roy University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Roy, Mantra, ""Speaking" Subalterns: A Comparative Study of African American and Dalit/Indian Literatures" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3441 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Speaking” Subalterns: A Comparative Study of African American and Dalit/Indian Literatures by Mantra Roy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Gurleen Grewal, Ph.D Co- Major Professor: Hunt Hawkins, Ph.D Elizabeth Hirsh, Ph.D Shirley Toland-Dix, Ph.D Date of Approval: March 16, 2010 Keywords: Race, Caste, Identity, Representation, Voice © Copyright 2010, Mantra Roy Acknowledgments I must thank James Baldwin for his book Nobody Knows My Name which introduced me to the world of African American literature and culture. Since that first encounter as a teenager I have come a long way today in terms of my engagement with the world of Black literature and with the ideas of equality, justice, and respect for humanity. -

Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in Central India, Its Wider Context and Historiography

Edinburgh Research Explorer Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in central India, its wider context and historiography Citation for published version: Bates, C 2008, 'Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in central India, its wider context and historiography', Paper presented at Savage Attack: adivasi insurrection in South Asia, Royal Asiatic Society, London, United Kingdom, 30/06/09 - 1/07/09. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Publisher Rights Statement: © Bates, C. (2008). Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in central India, its wider context and historiography. Paper presented at Savage Attack: adivasi insurrection in South Asia, Royal Asiatic Society, London, United Kingdom. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Adivasi Insurrections in India: the 1857 Rebellion in central India, its wider context and historiography (draft only – do not quote) Crispin Bates University of Edinburgh INTRODUCTION The adivasis of central India found themselves in the early nineteenth century in a time of flux, caught between the demands of competing hegemonies: the sub- empires of the Maratha Peshwa, and Bhonsle, Holkar and Scindia Rajas – all part of the Maratha confederacy – were in decline after the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803-05. -

Confronting the Violence Committed by Armed Opposition Groups

Nair: Confronting the Violence Committed by Armed Opposition Groups Confronting the Violence Committed by Armed Opposition Groups by Ravi Nair* 1 Human rights groups have limited their role to monitoring and protesting human rights violations committed by state actors.! With the emergence of armed opposition groups-such as the Sendero Luminoso in Peru2 and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka 3 -that murder, torture, and destroy civil society in their respective regions, human rights entities must question whether they should broaden their mandate to include abuses committed by such groups. Focusing on the context of India, this article: (1) develops arguments encouraging human rights groups to critique abuses perpetrated by armed opposition groups; (2) suggests potential problems that may be encountered in making such criticisms; and (3) raises some reasons for caution by human rights organizations that condemn the actions of armed opposition groups. I. THE TRADITIONAL MANDATE OF HUMAN RIGHTS GROUPS 2 The primary, if not the exclusive, mandate of human rights groups around the world has been to monitor, highlight, and struggle against wanton violations of human rights perpetrated by agencies of the State.4 .Ravi Nair is the Executive Director of the South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre ("SAHRDC") based in New Delhi, India <http://www.hri.ca/partners/sahrdc/index.htm>. 1. I use the term "state actor" to refer to states and those acting under the color of state authority. 2. See, e.g., Peru'sShining Path Kill Five in Grisly Attack on Border Town, AGENCE FRANCE- PRESSE, Dec. 8,1992, available in LEXIS, News Library, Arcnews File (describing an example of the terrorist activities of the Sendero Luminoso); Simon Strong, Where the Shining PathLeads, N.Y. -

243 Statement by Minister AUGUST 14, 1997 244 Notwithstanding What

243 Statement by Minister AUGUST 14, 1997 244 Notwithstanding what I have already said, I would like to SHRI PRAMOD MAHAJAN (Mumbai North-East) : Mr point out that since the dead body of Shri Sanjoy Ghosh has Speaker, Sir, Phoolan Devi is an honourable member of this not been recovered so far, in the strict legal sense, we cannot House. She is sitting outside, she must come inside. When declare that he is dead. Mulayam Singhji was the Chief Minister, he had withdrawn the cases filed against Phoolan Devi. As far as I know, as per law if Chief Minister or Home Minister withdraws a case and a [English] Court refuses to withdraw it, then, no Government can do anything in such a situation. The Court has opposed this SHRI KASHI RANA (Surat) : Sir, it is very important. All withdrawal. B.S.P. and BJP Governments have nothing to do the non-MPs from Gujarat ....(Interruptions) with it....(Interruptions) SHRI A.C. JOS (Idukki) : Sir, is it Bihar hour or is it Zero [English] Hour. MR. SPEAKER : You have made it clear DR. T. SUBBARAMI REDDY (Visakhapatnam) : Please see to it that Zero Hour is there. ....(Interruptions) SHRI A.C. JOS : We want no more of Bihar. We have had [Translation] enough of Bihar. THE MINISTER OF DEFENCE (SHRI MULAYAM SINGH DR. T. SUBBARAMI REDDY : We want Zero Hour. Every YADAV) : Pramod Mahajanji has mentioned my name in the day, we are talking only about Bihar. How long would we fight context of Phoolan Devi. We withdrew all cases and being a for Bihar? woman, on humanitarian ground ......(lnterruptions)\Ne are also not weak... -

No End to Crimes Against Dalits

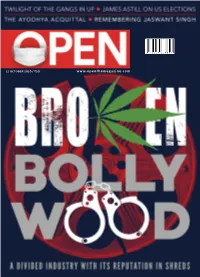

www.openthemagazine.com 50 12 OCTOBER /2020 OPEN VOLUME 12 ISSUE 40 12 OCTOBER 2020 CONTENTS 12 OCTOBER 2020 5 6 8 14 16 18 22 28 LOCOMOTIF INDRAPRASTHA MUMBAI TOUCHSTONE SOFT POWER WHISPERER IN MEMORIAM OPEN ESSAY The House of By Virendra Kapoor NOTEBOOK The sounds of our The Swami and the By Jayanta Ghosal Jaswant Singh Is it really over Jaswant Singh By Anil Dharker discontents Himalayas (1938-2020) for Trump? By S Prasannarajan By Keerthik Sasidharan By Makarand R Paranjape By MJ Akbar By James Astill and TCA Raghavan 32 32 BROKEN BOLLYWOOD Divided, self-referential in its storytelling, all too keen to celebrate mediocrity, its reputation in tatters and work largely stalled, the Mumbai film industry has hit rock bottom By Kaveree Bamzai 40 GRASS ROOTS Marijuana was not considered a social evil in the past and its return to respectability is inevitable in India By Madhavankutty Pillai 44 THE TWILIGHT OF THE GANGS 40 Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath has declared war on organised crime By Virendra Nath Bhatt 22 50 STATECRAFT Madhya Pradesh’s Covid opportunity By Ullekh NP 44 54 GLITTER IN GLOOM The gold loan market is cashing in on the pandemic By Nikita Doval 50 58 62 64 66 BETWEEN BODIES AND BELONGING MIND AND MACHINE THE JAISHANKAR DOCTRINE NOT PEOPLE LIKE US A group exhibition imagines Novels that intertwine artificial Rethinking India’s engagement Act two a multiplicity of futures intelligence with ethics with its enemies and friends By Rajeev Masand By Rosalyn D’Mello By Arnav Das Sharma By Siddharth Singh Cover by Saurabh Singh 12 OCTOBER 2020 www.openthemagazine.com 3 OPEN MAIL [email protected] EDITOR S Prasannarajan LETTER OF THE WEEK MANAGING EDITOR PR Ramesh C EXECUTIVE EDITOR Ullekh NP By any criterion, 2020 is annus horribilis (‘Covid-19: The EDITOR-AT-LARGE Siddharth Singh DEPUTY EDITORS Madhavankutty Pillai Surge’, October 5th, 2020).