JOHN PHILLIPS and the SMALLS LIGHTHOUSES Part Two: the Lighthouse on the Smalls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life of William Douglass M.Inst.C.E

LIFE OF WILLIAM DOUGLASS M.INST.C.E. FORMERLY ENGINEER-IN-CHIEF TO THE COMMISSIONERS OF IRISH LIGHTS BY THE AUTHOR OF "THE LIFE OF SIR JAMES NICHOLAS DOUGLASS, F.R.S." PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION 1923 CONTENTS CHAPTER I Birth; ancestry; father enters the service of the Trinity House; history and functions of that body CHAPTER II Early years; engineering apprenticeship; the Bishop Rock lighthouses; the Scilly Isles; James Walker, F.R.S.; Nicholas Douglass; assistant to the latter; dangers of rock lighthouse construction; resident engineer at the erection of the Hanois Rock lighthouse. CHAPTER III James Douglass re-enters the Trinity House service and is appointed resident engineer at the new Smalls lighthouse; the old lighthouse and its builder; a tragic incident thereat; genius and talent. CHAPTER IV James Douglass appointed to erect the Wolf Rock lighthouse; work commenced; death of Mr. Walker; James then becomes chief engineer to the Trinity House; William succeeds him at the Wolf. CHAPTER V Difficulties and dangers encountered in the erection of the Wolf lighthouse; zeal and courage of the resident engineer; reminiscences illustrating those qualities. CHAPTER VI Description of the Wolf lighthouse; professional tributes on its completion; tremor of rock towers life therein described in graphic and cheery verses; marriage. CHAPTER VII Resident engineer at the erection of a lighthouse on the Great Basses Reef; first attempts to construct a lighthouse thereat William Douglass's achievement description of tower; a lighthouse also erected by him on the Little Basses Reef; pre-eminent fitness of the brothers Douglass for such enterprises. CHAPTER VIII Appointed engineer-in-chief to the Commissioners of Irish Lights; three generations of the Douglasses and Stevensons as lighthouse builders; William Tregarthen Douglass; Robert Louis Stevenson. -

Cardiff Corvey Reading the Romantic Text

CARDIFF CORVEY READING THE ROMANTIC TEXT Issue 11 (December 2003) Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research Cardiff University Cardiff Corvey is available on the web @ www.cf.ac.uk/encap/corvey ISSN 47-5988 © 2004 Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research Published by the Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research, Cardiff University. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro / 2.5, using Adobe InDesign CS; images and illustrations prepared using Adobe Illustrator CS and Adobe PhotoShop CS; final output rendered with Ado- be Acrobat 6 Professional. Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text is a fully peer-reviewed academic journal (as of Issue 5, November 2000), appearing online in Summer and Winter of each year. Based in Cardiff University’s Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research, Cardiff Corvey provides a variety of information, including articles, bibliographical material, conference details, and sample texts. Editor: Anthony Mandal. Advisory Editors: Peter Garside (Chair, Cardiff); Jane Aaron (Glamorgan), Stephen Behrendt (Nebraska), Emma Clery (Sheffield Hallam), Ed Copeland (Pomona College), Caroline Franklin (Swansea), Isobel Grundy (Alberta), David Hewitt (Aberdeen), Claire Lamont (Newcastle), Robert Miles (Stirling), Rainer Schöwerling (Paderborn), Christopher Skelton-Foord (Durham), Kathryn Sutherland (Oxford). SUBMISSIONS This periodical is only as substantial as the material it contains: therefore, we more than welcome any contributions that members of the academic community might wish to make. Articles we would be most interested in publishing include those addressing Romantic literary studies with an especial slant on book history, textual and bibliographical studies, the literary marketplace and the publishing world, and so forth. Papers of 5–8,000 words should be submitted by the beginning of April or October in order to make the next issue, if accepted. -

For Indian River County Histories

Index for Indian River County Histories KEY CODES TO INDEXES OF INDIAN RIVER COUNTY HISTORIES Each code represents a book located on our shelf. For example: Akerman Joe A, Jr., M025 This means that the name Joe Akerman is located on page 25 in the book called Miley’s Memos. The catalog numbers are the dewey decimal numbers used in the Florida History Department of the Indian River County Main Library, Vero Beach, Florida. Code Title Author Catalog No. A A History of Indian River County: A Sense of Sydney Johnston 975.928 JOH Place C The Indian River County Cook Book 641.5 IND E The History of Education in Indian River Judy Voyles 975.928 His County F Florida’s Historic Indian River County Charlotte 975.928.LOC Lockwood H Florida’s Hibiscus City: Vero Beach J. Noble Richards 975.928 RIC I Indian River: Florida’s Treasure Coast Walter R. Hellier 975.928 Hel M Miley’s Memos Charles S. Miley 975.929 Mil N Mimeo News [1953-1962] 975.929 Mim P Pioneer Chit Chat W. C. Thompson & 975.928 Tho Henry C. Thompson S Stories of Early Life Along the Beautiful Indian Anna Pearl 975.928 Sto River Leonard Newman T Tales of Sebastian Sebastian River 975.928 Tal Area Historical Society V Old Fort Vinton in Indian River County Claude J. Rahn 975.928 Rah W More Tales of Sebastian Sebastian River 975.928 Tal Area Historical Society 1 Index for Indian River County Histories 1958 Theatre Guild Series Adam Eby Family, N46 The Curious Savage, H356 Adams Father's Been to Mars, H356 Adam G, I125 John Loves Mary, H356 Alto, M079, I108, H184, H257 1962 Theatre Guild -

The Story of Our Lighthouses and Lightships

E-STORy-OF-OUR HTHOUSES'i AMLIGHTSHIPS BY. W DAMS BH THE STORY OF OUR LIGHTHOUSES LIGHTSHIPS Descriptive and Historical W. II. DAVENPORT ADAMS THOMAS NELSON AND SONS London, Edinburgh, and Nnv York I/K Contents. I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY, ... ... ... ... 9 II. LIGHTHOUSE ADMINISTRATION, ... ... ... ... 31 III. GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OP LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 39 IV. THE ILLUMINATING APPARATUS OF LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... 46 V. LIGHTHOUSES OF ENGLAND AND SCOTLAND DESCRIBED, ... 73 VI. LIGHTHOUSES OF IRELAND DESCRIBED, ... ... ... 255 VII. SOME FRENCH LIGHTHOUSES, ... ... ... ... 288 VIII. LIGHTHOUSES OF THE UNITED STATES, ... ... ... 309 IX. LIGHTHOUSES IN OUR COLONIES AND DEPENDENCIES, ... 319 X. FLOATING LIGHTS, OR LIGHTSHIPS, ... ... ... 339 XI. LANDMARKS, BEACONS, BUOYS, AND FOG-SIGNALS, ... 355 XII. LIFE IN THE LIGHTHOUSE, ... ... ... 374 LIGHTHOUSES. CHAPTER I. LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY. T)OPULARLY, the lighthouse seems to be looked A upon as a modern invention, and if we con- sider it in its present form, completeness, and efficiency, we shall be justified in limiting its history to the last centuries but as soon as men to down two ; began go to the sea in ships, they must also have begun to ex- perience the need of beacons to guide them into secure channels, and warn them from hidden dangers, and the pressure of this need would be stronger in the night even than in the day. So soon as a want is man's invention hastens to it and strongly felt, supply ; we may be sure, therefore, that in the very earliest ages of civilization lights of some kind or other were introduced for the benefit of the mariner. It may very well be that these, at first, would be nothing more than fires kindled on wave-washed promontories, 10 LIGHTHOUSES OF ANTIQUITY. -

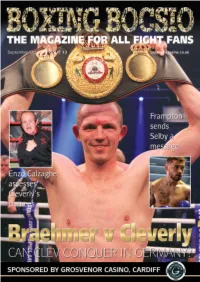

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

THE LIFE-BOAT the Journal of the Royal National Life-Boat Institution

THE LIFE-BOAT The Journal of the Royal National Life-boat Institution VOL. XXXIV DECEMBER, 1956 No. 378 THE LIFE-BOAT FLEET 155 Motor Life-boats 1 Harbour Pulling Life-boat LIVES RESCUED from the foundation of the Life-boat Service in 1824 to 30th September, 1956 80,491 Notes of the Quarter THE summer months of 1956 were increase in work has come at a time exceptionally arduous ones for the when a helicopter service is already crews of life-boat stations all round well established around our coasts. the coasts of Britain and Ireland. It The figures for 1956 offer the most was the busiest July in the whole conclusive answer to those who believe history of the service, with 129 that helicopters are beginning sub- launches compared with the previous stantially to reduce the work of life- record for July of 78 in 1952. August boats. was busier still, with 144 launches compared with the previous record of SERVICES TO YACHTSMEN 113 in August 1940. In July no fewer Of the 107 lives rescued during the than 153 lives were rescued, more than twenty-four hours from the 28th to 100 of them in one period of twenty- the 29th of July no fewer than 88 four hours between the 28th and the were from yachts, a number of those 29th of July. A full account of the rescued being children. A multiplicity activities of this memorable day of services to yachts has been a regular appears on page 322. feature of the work of the life-boats By the end of August more lives had during the summer months for a been rescued by life-boats in 1956 number of years, and it is gratifying than in the whole of 1955, and by the to record that increasing appreciation end of September life-boats had been of the services rendered by life-boats launched on service more often than is now being shown by yachtsmen. -

CCW Contract Science Report No: 762

Highly Protected Marine Reserves – Evidence of Benefits and Opportunities for Marine Biodiversity in Wales S. Gubbay CCW Contract Science Report No: 762 © CCGC/CCW 2006 You may reproduce this document free of charge for non-commercial purposes in any format or medium, provided that you do so accurately, acknowledging both the source and CCW's copyright, and do not use it in a misleading context. This is a report of research commissioned by the Countryside Council for Wales. However, the views and recommendations presented in this report are not necessarily those of the Council and should, therefore, not be attributed to the Countryside Council for Wales. Report series: CCW Contract Science Report Report number: 762 Publication date: December, 2006 Contract number: FC73-02-335 Contractor: Susan Gubbay Nominated officer(s): Gabrielle Wyn Title: Highly Protected Marine Reserves – Evidence of benefits and opportunities for marine biodiversity in Wales Author(s): S.Gubbay Restrictions: None Distribution list (core): CCW HQ Library, Bangor x1 CCW N Region Library, Mold x1 WAG Library x1 CCW N Region Library, Bangor x1 British Library x1 CCW SE Region Lib., Cardiff x1 NHM Library x1 CCW W Region Library, Llandeilo x1 JNCC Peterborough, Library x1 CCW W Region Library, Pemb x1 SNH Edinburgh, Library x1 CCW Skomer MNR x1 EN Peterborough Library x1 National Library of Wales x1 EHS Library x1 Distribution list (others): Jill Thomas, WAG x1 Wendy Twell , WAG x1 Kath Winnard , WAG x1 Keith Davies , CCW x1 John Hamer, CCW x1 Kirsty Dernie , CCW x1 Clare Eno, CCW x1 Natasha Lough, CCW x1 Gabrielle Wyn, CCW x1 Phil Newman, CCW x1 Bill Sanderson, CCW x1 Kirsten Ramsay,CCW x1 Catherine Duigan, CCW x1 Mike Camplin, CCW x1 Lucy Kay,CCW x1 Kate Smith,CCW x1 Ziggy Otto,CCW x1 Nicola Woodman, CCW x1 Recommended citation for this volume: Gubbay, S. -

Notes and Actions from Meeting Held on 13 January

CfER 03/06/2013 Agenda item 2 Council for Economic Renewal Meeting Notes of meeting held at 10.30 a.m. on Monday 28 January 2013 in Conference Room 1 & 2 Welsh Government Offices, Cathays Park, Cardiff Ministers in Attendance First Minister Minister for Business, Enterprise, Technology &Science Minister for Finance Minister Local Government and Communities (for Item 4) Stakeholders in Attendance Alex Bevan, Wales TUC Ben Cottam, ACCA Iestyn Davies, FSB Heather Eason, WSPU Ian Gallagher, Freight Transport Association Ifan Glyn, FMB (Observer) Richard Houdmont, CIM Peter Hughes, CML Leighton Jenkins, CBI Richard Jenkins, FMB Mark Judd, WSPU Nigel Keane, WSPU David Lermon, ICAEW Robert Lloyd Griffiths, IoD Martin Mansfield, Wales TUC David Morgan, RICS Graham Morgan, Chamber Wales Lowri Morgan, The Law Society John Phillips, Wales TUC Huw Roberts, IoD Amarjite Singh, Wales TUC Derek Walker, Wales Cooperative Centre Emma Watkins CBI Welsh Government Officials in Attendance Permanent Secretary James Price Tracey Burke Jeff Collins Alistair Davey Frances Duffy (Item 4) John McClelland (Item 3) Jonathan Price Alison Standfast (Item 3) Apologies: Paul Byard, Chair of Business Wales; Alex Jackman, Forum of Private Business; Nick Payne, Road Haulage Association; Richard Price, Home Builders Federation; Phil Orford, Forum of Private Business; Huw Thomas, NFU; Brendan Kelly, Wales TUC 1 CfER 03/06/2013 Agenda item 2 1. Introduction & Opening Remarks 1.1 The First Minister welcomed attendees to the meeting and introduced the agenda items. 1.2 The First Minister said that there were three main items on the agenda: • Agenda Item 3: Procurement with the Minister for Finance • Agenda Item 4: Transport and Connectivity with the Minister for Local Government and Communities • Agenda Item 5: Draft report on the Review of the Implementation and Impact of the Welsh Ministers’ Business Scheme 1.3 The First Minister explained that Item 4 would be moved to the end of the Agenda because the Minister for Local Government and Communities had been delayed. -

South Wales. [Kelly's • • Ship Chandlers

1178 SRI SOUTH WALES. [KELLY'S • • SHIP CHANDLERS. Thoma!l M. &; Co. 55 Jame!l stree~, Brodie Bros. 53 Bute street, Cardiff See Ship Store Dealer&.. Dock!, Cardiff Brukewich Selick &; Co. 113 :Bute st. Thoma~ Capt. John, Cb~nne} view, St. & West Bute st. Dock! &; Dock, head, SHIP FITTERS. Athan, Cowbridge West Bute dock, Cardiff . Thompson Matthew,I28 &; 129Exchange Cardigan Mercantile Co. Lim. (L. Keatmg Thom.lls', 61 Loudoun !!quare, buildings, Cardiff Lowthel', manager); offices,S Castle Dcc~s, CarditI Tillett Walter John &:; Co_ 17 Mount street, The Bridge, Cardigan! ShaddlCk ltobert, Lo?doun square, Dry Stuart square, Cardiff Oarlsen, Nielsen &; CO. II4 Bute st.Cdff dock, Docks, CardIff Volana Shipping Co. Lim.(John Mortis, Colley R. West Bute st. Docks, Oudiff SHIP OWNERS. agenti_ Post Office chambers, New Constantine, WarIer &; Co. Pier Head Dock road, Llanelly . chambers, 74 Bute street, Cardiff See also Steam, Ship Owners; also Wills G. H. &; Co. 59 -,Mount Stuart Crosby, Magee &; Moorsom, Pier Head Smack Owners. iquare, Cardiff) chambers, 74 Bute street, Cardiff Annin~ Brothe~, 70 Bute street,Cardiff SHIPS' PLUMBER. Davies W. L. &; Co. Dock, Penarth ArnatI &; Harrlson Queen's -chambers, Davies W. 26 Charles st.Milford Haven Gloucester pt &; South Dook, Swnsea Brown In. T. Bath lane, Swansea Dawson T. &; Co. Barry Dock, Cardiff Bacon In. &; Go. South dock, Swansea SHIP REPAIRERS Dawson &; Co. 103 Bute st. Cardiff Bacon John Lim. (John Phillips,agent), . '. Evans P. &. 00. Barry Dock, Cardiff 2 Murray crescent, J\Iilford Haven Bar~y Gravmg Dock &; Engmeermg Co. Evans Hugh, Barry Dock, Cardiff Bear Creek Oil &; Shipping Co.Lim. -

Coprolite 45

"0.45 November 2004 CoproVitf is compiled and produced by Tom Sharp?. Department of Geology, National Museum of Wales. Cardiff CFlO 3NP (tel 029 20 573265, fax 029 L0 ''~667332, e-mail [email protected]). It is Jb'1 pllhlished three times a year in March, June and November. Any material for inclusion should be sent to Tom sharpe by the first of the previous month, i.e. by 1 ] ] ] .T . 1 . l. ]a February, 1 May or 1October. (, ;l ~]~j,:~('~)]&s Coorokte 15 sponsored by Burhouse Ltd of Huddersfield, ' wholesale dlstr~butorsof rnlnerals, gemstones, gemstone prod~~ctsand lewellew components Chairman: Patriclc Wyse Jackson, Department of Geology, Trinity College, 2, Ireland tel +353 1 608 1477, fax +353 1 671 1199, e-mail wysjcknp@tcd.~e Secretary: Giles Miller, Department of Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 58D email [email protected] iTreasurer: Sara Chamhers, Curator of Natural Sciences, Royal Cornwall Museum, River Street, Truro, Cornwall TR1 251 tel 01872 272205, fax 01872 240514, email. [email protected] GCG website: http://www.geoc~rrator.org I Notice of Annual General Meeting Please note that the 31" AGM of the Geological Curators' Group will be held at 1620 on Tuesday 18 January 2005 at the Hancock Museum, Newcastle [upon Tvne, Nominations for the post of Chairman, Officers, and two Committee Memben ntwt be made by two members of the Group and submitted in writing to Giles Miller, GCC, Secretary, Department of Palaeontology, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD by Tuesday 28 December 2004. Subscriptions 2005: look out far your invoice This yeaL, instezd of-completing a subscriptioc form i:: Co,wo!;tc. -

Phillips Descendant Report

Descendants of William Phillips Generation 1 1. WILLIAM1 PHILLIPS was born on 21 Jun 1844 in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, Wales. He died on 02 Jan 1915 in Glais, Swansea, Wales (Station Road). He married (1) EMMA LLOYD, daughter of James Lloyd and Jane Davies on 29 Jan 1880 in Pontardawe, Glamorgan, Wales (St Peters Church). She was born on 23 Jun 1861 in Panteg, Monmouthshire, Wales (Pontymoile). She died on 10 Mar 1939 in Clydach, Swansea, Glamorgan (85 High Street). He married (2) RUTH RICHARDS, daughter of Thomas Richards on 16 May 1863 in Steynton, Pembrokeshire, Wales (St Peter's Church). She was born in Feb 1841 in Crymych, Pembrokeshire, Wales. She died on 13 Oct 1879 in Ystalyfera, Neath Port Talbot, Wales (237 Alltygrug Road). William Phillips and Emma Lloyd had the following children: 2. i. MAURICE2 PHILLIPS was born on 16 Apr 1888 in Glais, Swansea, Wales (Nicholas Road). He died on 23 Sep 1957 in Ida Villa, 1 Gored Cottages, Melincourt, Resolven, Neath. He married Annie Sophia Day, daughter of James Day and Gwenllian Evans on 27 Feb 1910 in Glais, Swansea, Wales (Seion Chapel). She was born on 18 Apr 1889 in Llanguicke, Glamorgan (Pontardawe 11a 748). She died on 07 Jul 1971 in Ida Villa, 1 Gored Cottages, Melincourt, Resolven, Neath. 3. ii. ELIZA JANE PHILLIPS was born on 29 Jan 1881 in Ystalyfera, Neath Port Talbot, Wales (Graigarw). She died on 27 Nov 1930 in Trebanos, Clydach, Swansea (Swansea Road). She married Walter Bendle, son of Joesph Bendle and Mary Jane ? on 23 Feb 1905 in Glais, Swansea, Wales (St Pauls Church). -

Keepers of Light History and Speculations on the Future of Icelandic Lighthouses

Keepers Of Light History and Speculations on the future of Icelandic Lighthouses Vikram Pradhan MA Design IUA Thesis Draft 3 20 November 2020 Keepers of Light 1 Introduction ighthouse L /ˈlʌɪthaʊs/ noun noun: lighthouse; plural noun: lighthouses 1. a tower or other structure containing a beacon light to warn or guide ships at sea. The Icelandic word for a lighthouse is viti, which means "to know," and know where one is sailing.1 Lighthouses are relics of a bygone age and engineering marvels that have stood the test of time. Structures such as the lighthouse enable us to see and understand the passing of history and participate in time cycles that surpass individual life. These structures are instruments and museums of time. In the greatest of buildings, time stands still, where matter, time, and space fuse into a singular individualistic experience, the sense of being. Lighthouses have been a place of wonder and awe for people around the world. They serve as reminders of our battles with the sea and are remembered for all their contributions towards saving lives. Its construction and history remind us of a time that has passed by and how it has witnessed human emotions, on and off the coast. Some of the oldest lighthouses in various parts of the world have witnessed two world wars, guiding ships and troops safely across seas; they have also been witness to many shipwrecks and some fascinating stories at sea. These structures have also played essential roles in the lives of the families that have been lighthouse keepers. Even though these structures are seen as mystical or poetic structures through symbolism in literature, art, and pop culture, the culture built through lighthouse keepers no longer exists.