Cardiff Corvey Reading the Romantic Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Indian River County Histories

Index for Indian River County Histories KEY CODES TO INDEXES OF INDIAN RIVER COUNTY HISTORIES Each code represents a book located on our shelf. For example: Akerman Joe A, Jr., M025 This means that the name Joe Akerman is located on page 25 in the book called Miley’s Memos. The catalog numbers are the dewey decimal numbers used in the Florida History Department of the Indian River County Main Library, Vero Beach, Florida. Code Title Author Catalog No. A A History of Indian River County: A Sense of Sydney Johnston 975.928 JOH Place C The Indian River County Cook Book 641.5 IND E The History of Education in Indian River Judy Voyles 975.928 His County F Florida’s Historic Indian River County Charlotte 975.928.LOC Lockwood H Florida’s Hibiscus City: Vero Beach J. Noble Richards 975.928 RIC I Indian River: Florida’s Treasure Coast Walter R. Hellier 975.928 Hel M Miley’s Memos Charles S. Miley 975.929 Mil N Mimeo News [1953-1962] 975.929 Mim P Pioneer Chit Chat W. C. Thompson & 975.928 Tho Henry C. Thompson S Stories of Early Life Along the Beautiful Indian Anna Pearl 975.928 Sto River Leonard Newman T Tales of Sebastian Sebastian River 975.928 Tal Area Historical Society V Old Fort Vinton in Indian River County Claude J. Rahn 975.928 Rah W More Tales of Sebastian Sebastian River 975.928 Tal Area Historical Society 1 Index for Indian River County Histories 1958 Theatre Guild Series Adam Eby Family, N46 The Curious Savage, H356 Adams Father's Been to Mars, H356 Adam G, I125 John Loves Mary, H356 Alto, M079, I108, H184, H257 1962 Theatre Guild -

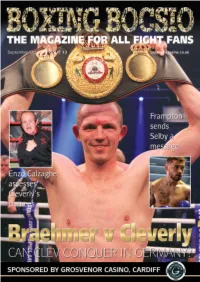

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

Notes and Actions from Meeting Held on 13 January

CfER 03/06/2013 Agenda item 2 Council for Economic Renewal Meeting Notes of meeting held at 10.30 a.m. on Monday 28 January 2013 in Conference Room 1 & 2 Welsh Government Offices, Cathays Park, Cardiff Ministers in Attendance First Minister Minister for Business, Enterprise, Technology &Science Minister for Finance Minister Local Government and Communities (for Item 4) Stakeholders in Attendance Alex Bevan, Wales TUC Ben Cottam, ACCA Iestyn Davies, FSB Heather Eason, WSPU Ian Gallagher, Freight Transport Association Ifan Glyn, FMB (Observer) Richard Houdmont, CIM Peter Hughes, CML Leighton Jenkins, CBI Richard Jenkins, FMB Mark Judd, WSPU Nigel Keane, WSPU David Lermon, ICAEW Robert Lloyd Griffiths, IoD Martin Mansfield, Wales TUC David Morgan, RICS Graham Morgan, Chamber Wales Lowri Morgan, The Law Society John Phillips, Wales TUC Huw Roberts, IoD Amarjite Singh, Wales TUC Derek Walker, Wales Cooperative Centre Emma Watkins CBI Welsh Government Officials in Attendance Permanent Secretary James Price Tracey Burke Jeff Collins Alistair Davey Frances Duffy (Item 4) John McClelland (Item 3) Jonathan Price Alison Standfast (Item 3) Apologies: Paul Byard, Chair of Business Wales; Alex Jackman, Forum of Private Business; Nick Payne, Road Haulage Association; Richard Price, Home Builders Federation; Phil Orford, Forum of Private Business; Huw Thomas, NFU; Brendan Kelly, Wales TUC 1 CfER 03/06/2013 Agenda item 2 1. Introduction & Opening Remarks 1.1 The First Minister welcomed attendees to the meeting and introduced the agenda items. 1.2 The First Minister said that there were three main items on the agenda: • Agenda Item 3: Procurement with the Minister for Finance • Agenda Item 4: Transport and Connectivity with the Minister for Local Government and Communities • Agenda Item 5: Draft report on the Review of the Implementation and Impact of the Welsh Ministers’ Business Scheme 1.3 The First Minister explained that Item 4 would be moved to the end of the Agenda because the Minister for Local Government and Communities had been delayed. -

South Wales. [Kelly's • • Ship Chandlers

1178 SRI SOUTH WALES. [KELLY'S • • SHIP CHANDLERS. Thoma!l M. &; Co. 55 Jame!l stree~, Brodie Bros. 53 Bute street, Cardiff See Ship Store Dealer&.. Dock!, Cardiff Brukewich Selick &; Co. 113 :Bute st. Thoma~ Capt. John, Cb~nne} view, St. & West Bute st. Dock! &; Dock, head, SHIP FITTERS. Athan, Cowbridge West Bute dock, Cardiff . Thompson Matthew,I28 &; 129Exchange Cardigan Mercantile Co. Lim. (L. Keatmg Thom.lls', 61 Loudoun !!quare, buildings, Cardiff Lowthel', manager); offices,S Castle Dcc~s, CarditI Tillett Walter John &:; Co_ 17 Mount street, The Bridge, Cardigan! ShaddlCk ltobert, Lo?doun square, Dry Stuart square, Cardiff Oarlsen, Nielsen &; CO. II4 Bute st.Cdff dock, Docks, CardIff Volana Shipping Co. Lim.(John Mortis, Colley R. West Bute st. Docks, Oudiff SHIP OWNERS. agenti_ Post Office chambers, New Constantine, WarIer &; Co. Pier Head Dock road, Llanelly . chambers, 74 Bute street, Cardiff See also Steam, Ship Owners; also Wills G. H. &; Co. 59 -,Mount Stuart Crosby, Magee &; Moorsom, Pier Head Smack Owners. iquare, Cardiff) chambers, 74 Bute street, Cardiff Annin~ Brothe~, 70 Bute street,Cardiff SHIPS' PLUMBER. Davies W. L. &; Co. Dock, Penarth ArnatI &; Harrlson Queen's -chambers, Davies W. 26 Charles st.Milford Haven Gloucester pt &; South Dook, Swnsea Brown In. T. Bath lane, Swansea Dawson T. &; Co. Barry Dock, Cardiff Bacon In. &; Go. South dock, Swansea SHIP REPAIRERS Dawson &; Co. 103 Bute st. Cardiff Bacon John Lim. (John Phillips,agent), . '. Evans P. &. 00. Barry Dock, Cardiff 2 Murray crescent, J\Iilford Haven Bar~y Gravmg Dock &; Engmeermg Co. Evans Hugh, Barry Dock, Cardiff Bear Creek Oil &; Shipping Co.Lim. -

Coprolite 45

"0.45 November 2004 CoproVitf is compiled and produced by Tom Sharp?. Department of Geology, National Museum of Wales. Cardiff CFlO 3NP (tel 029 20 573265, fax 029 L0 ''~667332, e-mail [email protected]). It is Jb'1 pllhlished three times a year in March, June and November. Any material for inclusion should be sent to Tom sharpe by the first of the previous month, i.e. by 1 ] ] ] .T . 1 . l. ]a February, 1 May or 1October. (, ;l ~]~j,:~('~)]&s Coorokte 15 sponsored by Burhouse Ltd of Huddersfield, ' wholesale dlstr~butorsof rnlnerals, gemstones, gemstone prod~~ctsand lewellew components Chairman: Patriclc Wyse Jackson, Department of Geology, Trinity College, 2, Ireland tel +353 1 608 1477, fax +353 1 671 1199, e-mail wysjcknp@tcd.~e Secretary: Giles Miller, Department of Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 58D email [email protected] iTreasurer: Sara Chamhers, Curator of Natural Sciences, Royal Cornwall Museum, River Street, Truro, Cornwall TR1 251 tel 01872 272205, fax 01872 240514, email. [email protected] GCG website: http://www.geoc~rrator.org I Notice of Annual General Meeting Please note that the 31" AGM of the Geological Curators' Group will be held at 1620 on Tuesday 18 January 2005 at the Hancock Museum, Newcastle [upon Tvne, Nominations for the post of Chairman, Officers, and two Committee Memben ntwt be made by two members of the Group and submitted in writing to Giles Miller, GCC, Secretary, Department of Palaeontology, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD by Tuesday 28 December 2004. Subscriptions 2005: look out far your invoice This yeaL, instezd of-completing a subscriptioc form i:: Co,wo!;tc. -

Phillips Descendant Report

Descendants of William Phillips Generation 1 1. WILLIAM1 PHILLIPS was born on 21 Jun 1844 in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, Wales. He died on 02 Jan 1915 in Glais, Swansea, Wales (Station Road). He married (1) EMMA LLOYD, daughter of James Lloyd and Jane Davies on 29 Jan 1880 in Pontardawe, Glamorgan, Wales (St Peters Church). She was born on 23 Jun 1861 in Panteg, Monmouthshire, Wales (Pontymoile). She died on 10 Mar 1939 in Clydach, Swansea, Glamorgan (85 High Street). He married (2) RUTH RICHARDS, daughter of Thomas Richards on 16 May 1863 in Steynton, Pembrokeshire, Wales (St Peter's Church). She was born in Feb 1841 in Crymych, Pembrokeshire, Wales. She died on 13 Oct 1879 in Ystalyfera, Neath Port Talbot, Wales (237 Alltygrug Road). William Phillips and Emma Lloyd had the following children: 2. i. MAURICE2 PHILLIPS was born on 16 Apr 1888 in Glais, Swansea, Wales (Nicholas Road). He died on 23 Sep 1957 in Ida Villa, 1 Gored Cottages, Melincourt, Resolven, Neath. He married Annie Sophia Day, daughter of James Day and Gwenllian Evans on 27 Feb 1910 in Glais, Swansea, Wales (Seion Chapel). She was born on 18 Apr 1889 in Llanguicke, Glamorgan (Pontardawe 11a 748). She died on 07 Jul 1971 in Ida Villa, 1 Gored Cottages, Melincourt, Resolven, Neath. 3. ii. ELIZA JANE PHILLIPS was born on 29 Jan 1881 in Ystalyfera, Neath Port Talbot, Wales (Graigarw). She died on 27 Nov 1930 in Trebanos, Clydach, Swansea (Swansea Road). She married Walter Bendle, son of Joesph Bendle and Mary Jane ? on 23 Feb 1905 in Glais, Swansea, Wales (St Pauls Church). -

Transforming Print: Key Issues Affecting the Development of Londonprintstudio John Phillips a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfil

1 Transforming Print: Key Issues Affecting the Development of londonprintstudio John Phillips A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2005 2 Content Introduction 3 Chapter 1: londonprintstudio: Facilities, Organisation and Programme 11 Chapter 2: The Research Context 25 Chapter 3: The Research Approach and Methodologies 33 Chapter 4: Communication Systems 49 Chapter 5: Oblivious and Illusive Print 63 Chapter 6: The Impact of Print in Europe 74 Chapter 7: Artists, Printmakers and Status 93 Chapter 8: Print Studios: The Pressure Behind the Press 110 Chapter 9: Origins and Development of londonprintstudio 127 Chapter 10: londonprintstudio’s Environment 137 Chapter 11: Conclusion: Contribution of the Study and Implications for Further Research 147 List of Illustrations 160 Endnotes 163 List of Appendices 187 Bibliography 190 3 Introduction Introduction original transparent 4 Introduction original in colour 5 Introduction This study, which informs the creation of a contemporary are less evident than the physical structure and the activities printmaking studio (londonprintstudio), stems from a encountered in the building. personal interest and long-term involvement in the provision The key aims of the research project were: of graphic arts and communication resources for artists, their i) the creation of a contemporary printstudio in the audiences and the wider community of people and context of London, namely the londonprintstudio, its organisations engaged in the provision of educational and facilities, organisation and programme; cultural facilities. ii) an analysis of the ideas and thinking that informed Throughout the project I acted as team leader, this practice-based project. -

RESCH, John Phillips?, 1940- ANGLO-AMERICAN EFFORTS in PRISON REFORM, 1850-1900: the WORK of THOMAS BARWICK LLOYD BAKER

This dissertation has been microillmed exactly as received 6«-22,195 RESCH, John Phillips?, 1940- ANGLO-AMERICAN EFFORTS IN PRISON REFORM, 1850-1900: THE WORK OF THOMAS BARWICK LLOYD BAKER. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1969 History, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan (E) Copyright by John Phillips Resch 1969 ANGLO-AMERICAN EFFORTS IN PRISON REFORM 1850- 1900 * THE WORK OF THOMAS BAHWICK LLOYD BAKER DISSERTATION Presented in Fkrtial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University * John Phillips Resch, B. A. , M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 1969 Approved by Adviser Department of History PREFACE Ihi3 dissertation is not a history of ideas and experiments which composed the prison reform movements in America and Ehgland. Its aim is to narrate and describe the work and ideas of Thomas Barwick Lloyd Baker of Gloucestershire, Ehgland against a background of prison reform efforts and administrative changes beginning with John Howard's report on prison conditions in 1777 and Quaker attempts in Philadelphia before the Revolu tionary War to create a reformatory prison discipline. Baker's role as the founder of the Ehglish system of small, private juvenile reformator ies, his idea for an adult reformatory and the Gloucestershire system of cumulative punishment, coupled with probation and police supervision which he helped to create and popularize, form the bulk of this paper. His Impact was not limited, however, just to his country nor to Ehglish reformers. Through correspondence, published works and personal acquaintances his work and ideas became part of the diffusion of ideas between Ehglish and American reformers. -

Phillips Genealogies; Including the Family of George Phillips, First

Gc M.l- 929.2 I P543p 1 1235120 GENEALOGY COLLECTION "^ ll^^'l^Mi,99,yf^.T,y. PUBLIC LIBRARY 3 1833 00726 7419 ^0 c\> ^ • ; PHILLIPS GENEALQaiES INCLUDING THE FAMILY OF GEORGE PHILLIPS, First Minister of Watertown, Mass., through most of the traceable branches from 1g30 to the present generation; ALSO THE FAMILIES OF EBRNEZER PHILLIPS, OF SOUTHBORO, MASS., THOMAS PHILLIPS, OF DUXBURY, MASS., THOMAS PHILLIPS, OF MARSHFIELD, MASS., JOHN PHILLIPS, OF EASTON, MASS., JAMES PHILLIPS, OF IPSWICH, MASS. WITH BRIEF GENEALOGIES OF WALTER PHILLIPS, OF DAMARISCOTTA, ME., ANDREW PHILLIPS, OF KITTERY, ME. MICHAEL, RICHAED, JEREMY AND JEREMIAH PHILLIPS, OF RHODE ISLAND; And Fragmentary Records, of early American Families of this name. AUBURN, MASS. COMPILED BY ALBERT M. PHILLIPS . 1885. PRESS OF CHAS. HAMILTON, WORCESTER, MASS. INTRODUCTION. ' A popular historian has said that the study of history ' sets before us striking examples of virtue, enterprise, courage, generosity, patriotism ; and, by a natural principle of emula- tion, incites us to copy such noble examples." We, of the present generation, know but little of the trials, fatigues, hardships, fears and anxieties, which our fathers and mothers of early New England days experienced and willingly endured, that they might establish a government and found a nation, where the privileges of civil and religious liberty, and the benefits of general education, should be the blessed inheritance of their posterity for all time. Having been accustomed to the even temperature and mild winters of the British Isles, the abrupt change of location, with unavoidable exposure to the harsher climate and rigorous win- ters of New England, caused many of the delicate ones among the first settlers to waste rapidly away with consumption or other unlooked-for diseases, while even the most vigorous of the first one or two generations after immigration, being subjected to the unceasing toil and the perils incident to early settle- ments, rarely attained the age of three-score and ten. -

History of the Kuykendall Family by George Benson Kuykendall Call Number: CS71.K98

History of the Kuykendall Family by George Benson Kuykendall Call Number: CS71.K98 This book contains the genealogy and history of the Kuykendall family of Dutch New York. Bibliographic Information: Kuykendall, George Benson. The Kuykendall Family. Kilham Stationery & Printing CO. Portland, Oregon. 1919. Copyright 1919 GEORGE BENSON KUYKENDALL, M. D. DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF MY FATHER JOHN KUYKENDALL Whose kindness, solicitude, watchcare and guiding hand, during the tender years of childhood and youth, whose fatherly counsels during young manhood, directed my purposes and kept me from straying. The memory of his nobility of character, his unswerving rectitude of principle and purpose, his devotion to right and splendid example, have been the guiding star of my life. As time has sped by, as the world, times and men have changed, his character and life have towered, as a great lighthouse, above the mists of the years, and illumined the voyage of my life. To him, to whom I owe the most of all I have ever been, or ever accomplished, of worth to myself or the world, I inscribe this volume, In grateful rememberance. CHAPTER CONTENTS CHAPTER I. Introductory Considerations. Object of this work--General indifference to family history--Kuykendall history covers a long time and wide area--Author's recollections of the past--Usual dryness of genealogy--Connecting up events in family history with contemporary events. CHAPTER II. Story of Search After History and Genealogy of Kuykendall Family. More than genealogical facts given--Author's knowledge of the family history--Family traditions--Sending searching party to Virginia--Difficulty in getting data-- Holland Society of New York--Findings of its genealogist. -

Australian Atomic Energy Commission

AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION TWENTY-SECOND ANNUAL REPORT Being the Commission's Report for the Year Ended 30 June 1974 AUSTRALIAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION AUSTRALIAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION To the Honourable R. F. X. Connor, M.P., Minister of State for Minerals and Energy, The Minister of State for Minerals and Energy Parliament House, The Honourable R. F. X. Connor, M.P. Canberra, A.C.T. Sir, In accordance with Section 31 of the Atomic Energy Act, Members of the Commission During the Year 1973-74 1953-73, we submit the Twenty-second Annual Report of the Australian Atomic Energy Commission, covering the Commission's operations for the financial year ended 30 June 1974. Chairman Financial accounts for the year, with a report on the accounts R. W. Boswell, O.B.E., M.Sc. by the Auditor-General as required by the Act, are appended to the report. A statement of the Commission's capital assets as at 30 June Deputy Chairman 1974 is also appended to the accounts. R. G. Ward, MA, Ph.D.(Cantab.) Yours faithfully, Members R. W. BOSWELL, Chairman. K. F. Alder, M.Sc., F.I.M. R. G. WARD, Deputy Chairman. Sir Lenox Hewitt, O.B.E., B.Com., F.A.S.A., A.C.I.S., L.C.A. K. F. ALDER, Member. C. L. HEWITT, Member. Secretary W. B. Lynch, B.A. 45 Beach Street, Coogee, N.S.W. 2034. 23 August 1974 Contents INTRODUCTION 9 Nuclear Energy 9 Uranium Resources . 10 Commission Program 11 Organisation 11 ADVISORY COMMITTEES 2 THE ROLE OF NUCLEAR POWER AS AN ENERGY RESOURCE 12 Energy Resources and Their Availability 12 Established Nuclear Power Systems 13 Appointed under Section 20 of the Atomic Energy Act, 1953-73 Table of World Nuclear Power Stations 14 Recent Developments . -

The Liverpool Nautical Research Society TRANSACTIONS 1949-50

The Liverpool Nautical Research Society TRANSACTIONS VOLUME V 1949-50 THE LIVERPOOL NAUTICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY " All de/iglu is in masts and oars and trim ships to cross the stormy sea."-ODYSSEY. TRANSACTIONS, VoL. V. 1949-50 CONTENTS PAGE COUNCIL AND OFFICERS 3 THE OBJECTS OF THE SOCIETY 3 LIBRARIES AND RESEARCH, by Eveline B. Saxton, Af.A. 4 THE FIRST AND SUBSEQUENT CHESHIRE LIGHTHOUSES, by John S. Rees 12 THE SOUTH AMERICAN MEAT TRADE, by Captain H. F. Pettit 22 TUGBOATS, by Captain Alan Henderson 29 The authors of papers alone are responsible for the statements and opinions in ·their several contributions ,Photographs are repro~u,ced by court~sy ,.of SYREN & SHIPPING, LTD. TRANSACTIONS 3 THE LIVERPOOL NAUTICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY (Founded 1938) President: SIR ERNEST B. RoYDEN, Bart. Chairman: JOHN S. REES, Esq. Hon. Treasurer: R. B. SUMMERFIELD, cjo Summerfield and Lang, Ltd., 28 Exchange Street East, Liverpool, 2. Tel. Central 9324 Hon. Secretary : ALEX M. FLETCHER, 24 Radnor Drive, Bootle, Liverpool, 20. Tel. Ainrree, 1216 Members of Council : ]. BETHEL, KEITH P. LEWIS, J. A. PUGH, G. R. SLOMAN, Prof. J. A. TODD The objects of the Society are :- 1. To encourage interest in the history of shipping (particularly local shipping) by collecting and collating material relating thereto ; 2. To undertake an historical survey of Liverpool vessels, their builders, owners and masters ; 3. To disseminate such information by publications or by any other available means ; 4. To co-operate in every suitable way with other organisations in Liverpool or elsewhere having similar or cognate objects ; 5. To encourage the making and collection of scale ship models, and their exhibition.