Download From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Itineraries Rousseau, N. 2019 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Rousseau, N. (2019). Itineraries: A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Itineraries A return to the archives of the South African truth commission and the limits of counter-revolutionary warfare ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen op woensdag 20 maart 2019 om 15.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door Nicky Rousseau geboren te Dundee, Zuid-Afrika promotoren: prof.dr. -

The Black Sash

THE BLACK SASH THE BLACK SASH MINUTES OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 CONTENTS: Minutes Appendix Appendix 4. Appendix A - Register B - Resolutions, Statements and Proposals C - Miscellaneous issued by the National Executive 5 Long Street Mowbray 7700 MINUTES OF THE BLACK SASH NATIONAL CONFERENCE 1990 - GRAHAMSTOWN SESSION 1: FRIDAY 2 MARCH 1990 14:00 - 16:00 (ROSEMARY VAN WYK SMITH IN THE CHAIR) I. The National President, Mary Burton, welcomed everyone present. 1.2 The Dedication was read by Val Letcher of Albany 1.3 Rosemary van wyk Smith, a National Vice President, took the chair and called upon the conference to observe a minute's silence in memory of all those who have died in police custody and in detention. She also asked the conference to remember Moira Henderson and Netty Davidoff, who were among the first members of the Black Sash and who had both died during 1989. 1.4 Rosemary van wyk Smith welcomed everyone to Grahamstown and expressed the conference's regrets that Ann Colvin and Jillian Nicholson were unable to be present because of illness and that Audrey Coleman was unable to come. All members of conference were asked to introduce themselves and a roll call was held. (See Appendix A - Register for attendance list.) 1.5 Messages had been received from Errol Moorcroft, Jean Sinclair, Ann Burroughs and Zilla Herries-Baird. Messages of greetings were sent to Jean Sinclair, Ray and Jack Simons who would be returning to Cape Town from exile that weekend. A message of support to the family of Anton Lubowski was approved for dispatch in the light of the allegations of the Minister of Defence made under the shelter of parliamentary privilege. -

PRENEGOTIATION Ln SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) a PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS of the TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS

PRENEGOTIATION lN SOUTH AFRICA (1985 -1993) A PHASEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE TRANSITIONAL NEGOTIATIONS BOTHA W. KRUGER Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Stellenbosch. Supervisor: ProfPierre du Toit March 1998 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: Date: The fmancial assistance of the Centre for Science Development (HSRC, South Africa) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the Centre for Science Development. Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za OPSOMMING Die opvatting bestaan dat die Suid-Afrikaanse oorgangsonderhandelinge geinisieer is deur gebeurtenisse tydens 1990. Hierdie stuC.:ie betwis so 'n opvatting en argumenteer dat 'n noodsaaklike tydperk van informele onderhandeling voor formele kontak bestaan het. Gedurende die voorafgaande tydperk, wat bekend staan as vooronderhandeling, het lede van die Nasionale Party regering en die African National Congress (ANC) gepoog om kommunikasiekanale daar te stel en sodoende die moontlikheid van 'n onderhandelde skikking te ondersoek. Deur van 'n fase-benadering tot onderhandeling gebruik te maak, analiseer hierdie studie die oorgangstydperk met die doel om die struktuur en funksies van Suid-Afrikaanse vooronderhandelinge te bepaal. Die volgende drie onderhandelingsfases word onderskei: onderhande/ing oor onderhandeling, voorlopige onderhande/ing, en substantiewe onderhandeling. Beide fases een en twee word beskou as deel van vooronderhandeling. -

FW De Klerk Foundation Conference on Uniting Behind the Constitution

FW de Klerk Foundation Conference on Uniting Behind the Constitution 2nd February 2013 DR HOLGER DIX, RESIDENT Representative OF THE KONRAD Adenauer Foundation FOR SOUTH Africa, AND FORMER PRESIDENT FW DE KLERK. On Saturday, 2 February 2013, the FW de Klerk Foundation hosted a successful conference at the Protea Hotel President in Bantry Bay, Cape Town. Themed “Uniting Behind the Constitution” and held in conjunction with the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, the conference was well attended by members of the public and a large press contingent. The speakers included thought leaders from civil society, business, academia and politics. This publication is a compendium of speeches presented on the day (speeches were transcribed from recordings), each relating to an important facet of the South African Constitution. Each speech was followed by a lively panel discussion, and panelists included: Dr Lucky Mathebula (board member of the FW de Klerk Foundation), John Kane-Berman (CEO of the South African Institute for Race Relations), Adv Paul Hoffman (Director of the Southern African Institute for Accountability), Adv Johan Kruger (Director of the Centre for Constitutional Rights), Dr Theuns Eloff (Vice-Chancellor of North-West University), Adv Johan Kruger SC (Acting Judge and board member of the FW de Klerk Foundation), Michael Bagraim (President of the Cape Chamber of Commerce), Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi (Leader of the IFP) and Paul Graham (Executive Director of the Institute for Democracy in South Africa). UpholdingCelebrating Diversity South -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Inkanyiso OFC 8.1 FM.Fm

21 The suppression of political opposition and the extent of violating civil liberties in the erstwhile Ciskei and Transkei bantustans, 1960-1989 Maxwell Z. Shamase 1 Department of History, University of Zululand [email protected] This paper aims at interrogating the nature of political suppression and the extent to which civil liberties were violated in the erstwhile Ciskei and Transkei. Whatever the South African government's reasons, publicly stated or hidden, for encouraging bantustan independence, by the time of Ciskei's independence ceremonies in December 1981 it was clear that the bantustans were also to be used as a more brutal instrument for suppressing opposition. Both Transkei and Ciskei used additional emergency-style laws to silence opposition in the run-up to both self- government and later independence. By the mid-1980s a clear pattern of brutal suppression of opposition had emerged in both bantustans, with South Africa frequently washing its hands of the situation on the grounds that these were 'independent' countries. Both bantustans borrowed repressive South African legislation initially and, in addition, backed this up with emergency-style regulations passed with South African assistance before independence (Proclamation 400 and 413 in Transkei which operated from 1960 until 1977, and Proclamation R252 in Ciskei which operated from 1977 until 1982). The emergency Proclamations 400, 413 and R252 appear to have been retained in the Transkei case and introduced in the Ciskei in order to suppress legal opposition at the time of attainment of self-government status. Police in the bantustans (initially SAP and later the Transkei and Ciskei Police) targeted political opponents rather than criminals, as the SAP did in South Africa. -

Political Violence in the Era of Negotiations and Transition, 1990-1994

Volume TWO Chapter SEVEN Political Violence in the Era of Negotiations and Transition, 1990-1994 I INTRODUCTION 1 The Commission had considerable success in uncovering violations that took place before 1990. This was not true of the 1990s period. Information before the Commission shows that the nature and pattern of political conflict in this later period changed considerably, particularly in its apparent anonymity. A comparatively smaller number of amnesty applications were received for this period. The investigation and research units of the Commission were also faced with some difficulty in dealing with the events of the more recent past. 2 Two factors dominated the period 1990–94. The first was the process of negotiations aimed at democratic constitutional dispensation. The second was a dramatic escalation in levels of violence in the country, with a consequent increase in the number of gross violations of human rights. 3 The period opened with the public announcement of major political reforms by President FW de Klerk on 2 February 1990 – including the unbanning of the ANC, PAC, SACP and fifty-eight other organisations; the release of political prisoners and provision for all exiles to return home. Mr Nelson Mandela was released on 11 February 1990. The other goals were achieved through a series of bilateral negotiations between the government and the ANC, resulting in the Groote Schuur and Pretoria minutes of May and August 1990 respectively. The latter minute was accompanied by the ANC’s announcement that it had suspended its armed struggle. 4 A long period of ‘talks about talks’ followed – primarily between the government, the ANC and Inkatha – culminating in the December 1991 launch of the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA). -

AK2117-J2-3-C102-001-Jpeg.Pdf

^m - fc V , m ■*. V C 0 JSITENTJ 5 Note: This booklet 1n It s present form 1s not complete but ha< hAnn SS*El?,e t0 y0U “ th,S P01"‘ 1" 1. Declaration of the United Democratic Front 2. UDF National Executive Coimrittee 3. UDF Regional Executive Committees 4. Statement of the UDF National General Council 5. Secretarial Report 6. Working Principles 7. Resolutions: Detentions and Treason Trial Banning of the UDF and A ffiliates in the Bantustans UDF International Relations Trade Unions- - — * — . Unemployment Forced Removals Rural Areas Militarisation (• Women ' Black Local Authorities Tricameral Parliament and Black Forum ) - Citizenship Imperialism Imperialism USA International Year of the Youth Education Namibia * New Zealand Rugby Tour 3 Declaration of the United Democratic Front We. the freedom loving people of South Africa, say with one voice to tbe whole worio that we • cherish the vision o f a united. demooaU . South A fno based on the wa of the people. • wa strive for the unity of a l people am «h united • the cpprKs^andesploitation °f w om en w a con- > onue. Women wil suffer greater rurdshcn under me acfonagamsttheevasof apartheid, econaac and al mw other forms of e«*xoOon ^ WomefV wtf be (Evicted from their ctwW* fen md fjmftes. P iw iy snd malnutrition wfli continue Ana. In our march to a free and Job South Africa, we are guided by these noble £ S J S t ^ ti & bnn'* *wh6fl**'■** Ideals *Sr Potion of a true deecracv In which a i South Africans W participate h a t govern- ment of our councrr. -

The Cassinga Massacre of Namibian Exiles in 1978 and the Conflicts Between Survivors’ Memories and Testimonies

ENDURING SUFFERING: THE CASSINGA MASSACRE OF NAMIBIAN EXILES IN 1978 AND THE CONFLICTS BETWEEN SURVIVORS’ MEMORIES AND TESTIMONIES BY VILHO AMUKWAYA SHIGWEDHA A Dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of the Western Cape December 2011 Supervisor: Professor Patricia Hayes ABSTRACT During the peak of apartheid, the South African Defence Force (SADF) killed close to a thousand Namibian exiles at Cassinga in southern Angola. This happened on May 4 1978. In recent years, Namibia commemorates this day, nationwide, in remembrance of those killed and disappeared following the Cassinga attack. During each Cassinga anniversary, survivors are modelled into „living testimonies‟ of the Cassinga massacre. Customarily, at every occasion marking this event, a survivor is delegated to unpack, on behalf of other survivors, „memories of Cassinga‟ so that the inexperienced audience understands what happened on that day. Besides survivors‟ testimonies, edited video footage showing, among others, wrecks in the camp, wounded victims laying in hospital beds, an open mass grave with dead bodies, SADF paratroopers purportedly marching in Cassinga is also screened for the audience to witness the agony of that day. Interestingly, the way such presentations are constructed draw challenging questions. For example, how can the visual and oral presentations of the Cassinga violence epitomize actual memories of the Cassinga massacre? How is it possible that such presentations can generate a sense of remembrance against forgetfulness of those who did not experience that traumatic event? When I interviewed a number of survivors (2007 - 2010), they saw no analogy between testimony (visual or oral) and memory. They argued that memory unlike testimony is personal (solid, inexplicable and indescribable). -

The Apartheid Divide

PUNC XI: EYE OF THE STORM 2018 The Apartheid Divide Sponsored by: Presented by: Table of Contents Letter from the Crisis Director Page 2 Letter from the Chair Page 4 Committee History Page 6 Delegate Positions Page 8 Committee Structure Page 11 1 Letter From the Crisis Director Hello, and welcome to The Apartheid Divide! My name is Allison Brown and I will be your Crisis Director for this committee. I am a sophomore majoring in Biomedical Engineering with a focus in Biochemicals. This is my second time being a Crisis Director, and my fourth time staffing a conference. I have been participating in Model United Nations conferences since high school and have continued doing so ever since I arrived at Penn State. Participating in the Penn State International Affairs and Debate Association has helped to shape my college experience. Even though I am an engineering major, I am passionate about current events, politics, and international relations. This club has allowed me to keep up with my passion, while also keeping with my other passion; biology. I really enjoy being a Crisis Director and I am so excited to do it again! This committee is going to focus on a very serious topic from our world’s past; Apartheid. The members of the Presidents Council during this time were quite the collection of people. It is important during the course of this conference that you remember to be respectful to other delegates (both in and out of character) and to be thoughtful before making decisions or speeches. If you ever feel uncomfortable, please inform myself or the chair, Sneha, and we will address the issue. -

The Referendum in FW De Klerk's War of Manoeuvre

The referendum in F.W. de Klerk’s war of manoeuvre: An historical institutionalist account of the 1992 referendum. Gary Sussman. London School of Economics and Political Science. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and International History, 2003 UMI Number: U615725 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615725 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 T h e s e s . F 35 SS . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract: This study presents an original effort to explain referendum use through political science institutionalism and contributes to both the comparative referendum and institutionalist literatures, and to the political history of South Africa. Its source materials are numerous archival collections, newspapers and over 40 personal interviews. This study addresses two questions relating to F.W. de Klerk's use of the referendum mechanism in 1992. The first is why he used the mechanism, highlighting its role in the context of the early stages of his quest for a managed transition. -

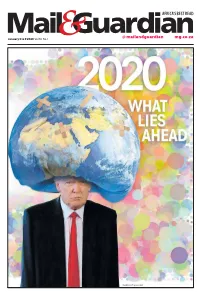

Africa's Best Read

AFRICA’S BEST READ January 3 to 9 2020 Vol 36 No 1 @ mailandguardian mg.co.za Illustration: Francois Smit 2 Mail & Guardian January 3 to 9 2020 Act or witness IN BRIEF – THE NEWS YOU MIGHT HAVE MISSED Time called on Zulu king’s trust civilisation’s fall The end appears to be nigh for the Ingonyama Trust, which controls more than three million A decade ago, it seemed that the climate hectares of land in KwaZulu-Natal on behalf crisis was something to be talked about of King Goodwill Zwelithini, after the govern- in the future tense: a problem for the next ment announced it will accept the recommen- generation. dations of the presidential high-level panel on The science was settled on what was land reform to review the trust’s operations or causing the world to heat — human emis- repeal the legislation. sions of greenhouse gases. That impact Minister of Agriculture, Land Reform and had also been largely sketched out. More Rural Development Thoko Didiza announced heat, less predictable rain and a collapse the decision to accept the recommendations in the ecosystems that support life and and deal with barriers to land ownership human activities such as agriculture. on land controlled by amakhosi as part of a But politicians had failed to join the dots package of reforms concerned with rural land and take action. In 2009, international cli- tenure. mate negotiations in Copenhagen failed. She said rural land tenure was an “immedi- Other events regarded as more important ate” challenge which “must be addressed.” were happening.