Kobe University Repository : Kernel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Outsiders' Music: Progressive Country, Reggae

CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s Chapter Outline I. The Outlaws: Progressive Country Music A. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, mainstream country music was dominated by: 1. the slick Nashville sound, 2. hardcore country (Merle Haggard), and 3. blends of country and pop promoted on AM radio. B. A new generation of country artists was embracing music and attitudes that grew out of the 1960s counterculture; this movement was called progressive country. 1. Inspired by honky-tonk and rockabilly mix of Bakersfield country music, singer-songwriters (Bob Dylan), and country rock (Gram Parsons) 2. Progressive country performers wrote songs that were more intellectual and liberal in outlook than their contemporaries’ songs. 3. Artists were more concerned with testing the limits of the country music tradition than with scoring hits. 4. The movement’s key artists included CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s a) Willie Nelson, b) Kris Kristopherson, c) Tom T. Hall, and d) Townes Van Zandt. 5. These artists were not polished singers by conventional standards, but they wrote distinctive, individualist songs and had compelling voices. 6. They developed a cult following, and progressive country began to inch its way into the mainstream (usually in the form of cover versions). a) “Harper Valley PTA” (1) Original by Tom T. Hall (2) Cover version by Jeannie C. Riley; Number One pop and country (1968) b) “Help Me Make It through the Night” (1) Original by Kris Kristofferson (2) Cover version by Sammi Smith (1971) C. -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. -

Sheet1 Page 1 809 Band Jam Session BLANK (Hit

Sheet1 809 Band Jam Session BLANK (Hit Factor) Digital Near Mint $200 Al Brown Here I Am baby, come and Tit for Tat Roots VG+ $200 take me Al Senior Bonopart Retreat Coxsone Rocksteady VG $200 Old time Repress Baby Cham Man and Man Xtra Large Dancehall 2000 EXCELLENT $100 Baby Wayne Gal fi come in a dance free Upstairs Ent. Dancehall 95-99 EXCELLENT $100 Banana Man Ruling Sound Taurus Digital clash tune EXCELLENT $250 Benaiah Tonight is the night Cosmic Force Records Roots instrumental EXCELLENT $150 Beres Hammond Double trouble Steely & Clevie Reggae Digital VG+ $150 Beres Hammond They gonna talk Harmony House Roots // Lovers VG+ $150 Big Joe & Bim Sherman Natty cale Scorpio Roots VG+ $400 Big Youth Touch me in the morning Agustus Buchanan Roots VG++ $200 Billy Cole Extra careful Recrational & Educational Reggae Funk EXCELLENT $600 Bob Andy Games people play // Sun BLANK (FRM) Rocksteady VG+ // VG $400 shines for me Bob Marley & The Wailers I'm gonna put it on Coxsone SKA Good+ to VG- $350 Brigadier Jerry Pain Jwyanza Roots DJ EXCELLENT $200 answer riddim Buju Banton Big it up Mad House Dancehall 90's EXCELLENT $100 Carl Dawkins Satisfaction Techniques Reggae // Rocksteady Strong VG $200 Repress Carol Kalphat Peace Time Roots Rock International Roots VG+ $300 Chosen Few Shaft Crystal Reggae Funk VG $250 Clancy Eccles Feel the rhythm // Easy BLANK (Randy's) Reggae // Rocksteady Strong VG $500 snappin Clyde Alphonso // Carey Let the music play // More BLANK (Muzik City) Rocksteady VG $1200 El Flip toca VG Johnson Scorcher pero sin peso -

April 2021 New Releases

April 2021 New Releases SEE PAGE 15 what’s featured exclusives inside PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately 79 Music [MUSIC] Vinyl 3 CD 11 ROY ORBISON - HEMINGWAY, A FILM BY JON ANDERSON - FEATURED RELEASES Video THE CAT CALLED DOMINO KEN BURNSAND LYNN OLIAS OF SUNHILLOW: 48 NOVICK. ORIGINAL 2 DISC EXPANDED & Film MUSIC FROM THE PBS REMASTERED DOCUMENTARY Films & Docs 50 MVD Distribution Independent Releases 78 Order Form 81 Deletions & Price Changes 84 THE FINAL COUNTDOWN DONNIE DARKO (UHD) ACTION U.S.A. 800.888.0486 (3-DISC LIMITED 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 EDITION/4K UHD+BLU- www.MVDb2b.com RAY+CD) WO FAT - KIM WILSON - SLY & ROBBIE - PSYCHEDELONAUT TAKE ME BACK RED HILLS ROAD DONNIE DARKO SEES THE LIGHT! The 2001 thriller DONNIE DARKO gets the UHD/4K treatment this month from Arrow Video, a 2-disc presentation that shines a crisp light on this star-studded film. Counting PATRICK SWAYZE and DREW BARRYMORE among its luminous cast, this first time on UHD DONNIE DARKO features the film and enough extras to keep you in the Darko for a long time! A lighter shade of dark is offered in the limited-edition steelbook of ELVIRA: MISTRESS OF THE DARK, a horror/comedy starring the horror hostess. Brand new artwork and an eye-popping Hi-Def presentation. Blue Underground rises again in the 4K department, with a Bluray/UHD/CD special of THE FINAL COUNTDOWN. The U.S.S. Nimitz is hurled back into time and can prevent the attack on Pearl Harbor! With this new UHD version, the KIRK DOUGLAS-led crew can see the enemy with crystal clarity! You will not believe your eyes when you witness the Animal Kingdom unleashed with two ‘Jaws with Claws’ horror movies from Severin Films, GRIZZLY and DAY OF THE ANIMALS. -

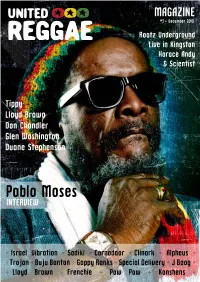

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures. -

The Mighty Diamonds Deeper Roots Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Mighty Diamonds Deeper Roots mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Deeper Roots Country: Jamaica Released: 1979 Style: Roots Reggae, Dub MP3 version RAR size: 1947 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1322 mb WMA version RAR size: 1712 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 555 Other Formats: DMF WMA VOX AU MP1 AUD WAV Tracklist A1 Reality 3:15 A2 Blackman 3:48 A3 Dreadlocks Time 3:16 A4 Diamonds And Pearls 3:01 A5 One Brother Short 3:45 B1 Bodyguard 3:31 B2 4000 Years 3:30 B3 Master Plan 4:01 B4 Two By Two 3:35 B5 Be Aware 2:49 Credits Arranged By – Jo Jo*, The Mighty Diamonds Drums – Carlton 'Santa' Davis* Engineer – Anthony Graham (Crucial Bunny)*, Ernest Hookim, L. McKensie (Maxie)* Harmony Vocals – Lloyd Ferguson (Judge)* Harmony Vocals, Body Percussion – Fitzroy Simpson (Bunny)* Lead Guitar – Earl 'Chinna' Smith* Lead Vocals – Donald Shaw (Tabby)* Mastered By – JONZ* Mixed By – Ernest Hoo Kim (The Genius)* Organ – Winston 'Jelly Belly' Wright* Percussion – Bunny Diamond, Sky Juice Piano – Gladstone 'Gladdy' Anderson* Producer – Joseph Hookim 'Jo Jo'* Rhythm Guitar – Albert 'Tony' Chin* Saxophone – Dean 'Youth Sax' Frazer* Trombone – Ronald "Nambo" Robinson Trumpet – Dean "Youth Sax" Fraser*, Junior "Chico" Chin Trumpet [Mini] – Arnold 'Willy' Brakenbridge* Notes Recorded at Channel One Studio, 29 Maxfield Avenue, Kingston 13, Jamaica, W.I. Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout: FLD- 6001 - A 1 Matrix / Runout: FLD - 6001 - B1 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Deeper Roots (Back To -

Street Hype Newspaper and Its Publishers

Patriece B. Miller Funeral Service, Inc. Licensed Funeral Director From Westmoreland, Jamaica WI • Shipping Local & Overseas ‘Community Lifestyle Newspaper’ 914-310-4294 Vol: 8 No. 09 WWW.STREETHYPENEWSPAPER.COM • FREE COPY MAY 1-18, 2013 Court Restrains Pastor By Shirley Irons, Contributing Writer he Bronx Supreme Court has intervened in the ongoing Ttwo-year financial dispute between the Board of Trustees and Pastor Ivan Plummer of the Emmannuel Seventh Day Church Ministries in the Bronx. According to court docu- titles of the ments obtained by Street Hype, church's real or the Board of Trustees and the personal proper- Happy members alleged that Plummer ties to anyone. with the help of other church The court also officers misappropriated and decided that embezzled church funds and had Plummer acted C a r i b b e a n taken over sole control of all the unilaterally Mother’s Day Pastor Ivan church assets. Plummer when he entered See Page 11 & 13 Flavor The members also claimed into the agree- Rasta Pasta that Plummer had entered into an ment on behalf of the church and agreement with an “associate” on declared that agreement null and Jerk Chicken behalf of the church without con- void. Curry Coconut Salmon sulting the trustees and he had He was further ordered to Brown Stew Salmom refused to provide a financial present a written financial Run Down Snapper accounting of the church's assets accounting of the church's assets and funds with an estimated to the members and to comply by Jerk Salmon value of nearly $1 million. -

Samson and Moses As Moral Exemplars in Rastafari

WARRIORS AND PROPHETS OF LIVITY: SAMSON AND MOSES AS MORAL EXEMPLARS IN RASTAFARI __________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board __________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________________ by Ariella Y. Werden-Greenfield July, 2016 __________________________________________________________________ Examining Committee Members: Terry Rey, Advisory Chair, Temple University, Department of Religion Rebecca Alpert, Temple University, Department of Religion Jeremy Schipper, Temple University, Department of Religion Adam Joseph Shellhorse, Temple University, Department of Spanish and Portuguese © Copyright 2016 by Ariella Y. Werden-Greenfield All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Since the early 1970’s, Rastafari has enjoyed public notoriety disproportionate to the movement’s size and humble origins in the slums of Kingston, Jamaica roughly forty years earlier. Yet, though numerous academics study Rastafari, a certain lacuna exists in contemporary scholarship in regards to the movement’s scriptural basis. By interrogating Rastafari’s recovery of the Hebrew Bible from colonial powers and Rastas’ adoption of an Israelite identity, this dissertation illuminates the biblical foundation of Rastafari ethics and symbolic registry. An analysis of the body of scholarship on Rastafari, as well as of the reggae canon, reveals