Differences in Implementation of Family Focused Practice in Hospitals: a Cross-Sectional Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Detailed-Program-6Th-Ocher-2017

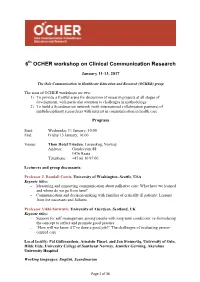

6th OCHER workshop on Clinical Communication Research January 11-13, 2017 The Oslo Communication in Healthcare Education and Research (OCHER) group The aims of OCHER workshops are two: 1) To provide a fruitful arena for discussion of research projects at all stages of development, with particular attention to challenges in methodology 2) To build a Scandinavian network (with international collaboration partners) of multidisciplinary researchers with interest in communication in health care Program Start: Wednesday 11 January, 10:00 End: Friday 13 January, 16:00 Venue: Thon Hotel Triaden, Lørenskog, Norway Address: Gamleveien 88 1476 Rasta Telephone: +47 66 10 97 00 Lecturers and group discussants: Professor J. Randall Curtis, University of Washington, Seattle, USA Keynote titles: - Measuring and improving communication about palliative care: What have we learned and where do we go from here? - Communication and decision-making with families of critically ill patients: Lessons from the successes and failures Professor Vikki Entwistle, University of Aberdeen, Scotland, UK Keynote titles: - Support for self-management among people with long-term conditions: re-formulating the concept to reflect and promote good practice - “How will we know if I’ve done a good job?” The challenges of evaluating person- centred care Local faculty: Pål Gulbrandsen, Arnstein Finset, and Jan Svennevig, University of Oslo, Hilde Eide, University College of Southeast Norway, Jennifer Gerwing, Akershus University Hospital Working languages: English, Scandinavian Page 1 of 36 Wednesday January 11 Time Activity Plenary room / Room A Room B 1000 Plenary Introduction, mutual presentation 1045 Break 1100 Plenary Vikki Entwistle Support for self-management keynote 1 among people with long-term conditions: re-formulating the concept to reflect and promote good practice 1230 Lunch 1315 Plenary J. -

Norwegian Journal of Epidemiology Årgang 27, Supplement 1, Oktober 2017 Utgitt Av Norsk Forening for Epidemiologi

1 Norsk Epidemiologi Norwegian Journal of Epidemiology Årgang 27, supplement 1, oktober 2017 Utgitt av Norsk forening for epidemiologi Redaktør: Trond Peder Flaten EN NORSKE Institutt for kjemi, D 24. Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet, 7491 Trondheim EPIDEMIOLOGIKONFERANSEN e-post: [email protected] For å bli medlem av Norsk forening for TROMSØ, epidemiologi (NOFE) eller abonnere, send e-post til NOFE: [email protected]. 7.-8. NOVEMBER 2017 Internettadresse for NOFE: http://www.nofe.no e-post: [email protected] WELCOME TO TROMSØ 2 ISSN 0803-4206 PROGRAM OVERVIEW 3 Opplag: 185 PROGRAM FOR PARALLEL SESSIONS 5 Trykk: NTNU Grafisk senter Layout og typografi: Redaktøren ABSTRACTS 9 Tidsskriftet er åpent tilgjengelig online: LIST OF PARTICIPANTS 86 www.www.ntnu.no/ojs/index.php/norepid Også via Directory of Open Access Journals (www.doaj.org) Utgis vanligvis med to regulære temanummer pr. år. I tillegg kommer supplement med sammendrag fra Norsk forening for epidemiologis årlige konferanse. 2 Norsk Epidemiologi 2017; 27 (Supplement 1) The 24th Norwegian Conference on Epidemiology Tromsø, November 7-8, 2017 We would like to welcome you to Tromsø and the 24th conference of the Norwegian Epidemiological Association (NOFE). The NOFE conference is an important meeting point for epidemiologists to exchange high quality research methods and findings, and together advance the broad research field of epidemiology. As in previous years, there are a diversity of topics; epidemiological methods, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, nutrition, female health, musculo-skeletal diseases, infection and behavioral epidemiology, all within the framework of this years’ conference theme; New frontiers in epidemiology. The conference theme reflects the mandate to pursue methodological and scientific progress and to be in the forefront of the epidemiological research field. -

Perinatal Depression and Anxiety in Women with Multiple Sclerosis: a Population-Based Cohort Study

Published Ahead of Print on April 21, 2021 as 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012062 Neurology Publish Ahead of Print DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012062 Perinatal Depression and Anxiety in Women with Multiple Sclerosis: A Population-Based Cohort Study Author(s): Karine Eid, MD1,2; Øivind Fredvik Torkildsen, MD PhD1,3; Jan Aarseth, PhD3,4,5; Heidi Øyen Flemmen, MD6; Trygve Holmøy, MD PhD7,8; Åslaug Rudjord Lorentzen, MD PhD9; Kjell-Morten Myhr, MD PhD1,3; Trond Riise, PhD3,5,10; Cecilia Simonsen, MD8,11; Cecilie Fredvik Torkildsen, MD1,12; Stig Wergeland, MD PhD2,3,4; Johannes Sverre 13,14 15 1,2 1,2 Willumsen, MD ; Nina Øksendal, MD ; Nils Erik Gilhus, MD PhD ; Marte-Helene Bjørk, MD PhD Note 1. The Article Processing Charge was funded by the Western Norway Regional Health Authority. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives License 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND), which permits downloading and sharing the work provided it is properly cited. The work cannot be changed in any way or used commercially without permission from the journal. Neurology® Published Ahead of Print articles have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication. This manuscript will be published in its final form after copyediting, page composition, and review of proofs. Errors that could affect the content may be corrected during these processes. Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. on behalf of the American Academy of Neurology. Corresponding Author: Karine Eid [email protected] Affiliation Information for All Authors: 1. -

THE NORTHERN NORWAY REGIONAL HEALTH AUTHORITY (Helse Nord RHF)

THE NORTHERN NORWAY REGIONAL HEALTH AUTHORITY (Helse Nord RHF) Northern Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse Nord RHF) is responsible for the public hospitals in northern Norway. The hospitals are organised in five trusts: • Finnmark Hospital Trust • University Hospital of Northern Norway Trust • Nordland Hospital Trust • Helgeland Hospital Trust • Hospital Pharmacy of North Norway Trust The trusts have their own management boards and are independent legal entities. Sector Healthcare Locations The four hospital Trusts are located in all of North Norway and Svalbard. Size Enterprise Data 5000 users since its launch in early 2011, will scale to approx. 12,500 users by the end of 2014. Company Website www.helse-nord.no For Reference Trond Kristiansen, E-Learning advisor. Nordland Hospital Trust Email - [email protected] Tel. +47 470 12 344 Øystein Lorentzen, Manager for IT Nordland Hospital Trust Email - [email protected] Tel. +47 900 40 566 THE NORTHERN NORWAY REGIONAL HEALTH AUTHORITY (Helse Nord RHF) Case Study Copyright © 2013 Docebo S.p.A. All rights reserved. Docebo is either a registered trademark or trademark of Docebo S.p.A. Other marks are the properties of their respective owners. To contact Docebo, please visit: www.docebo.com Company Customer Challenge The Northern Norway Regional Hospitals are often large and very Health Authority (Helse Nord RHF) complex organizations and is responsible for the public Docebo’s functionality fulfills many hospitals in northern Norway. of our needs right out of the box. The Regional Health Authority was Only basic customization with little established on the 1st January or no development is needed to "THROUGH COOPERATION 2002 when the central government implement the Docebo solution. -

Day Surgery in Norway 2013–2017

Day surgery in Norway 2013–2017 A selection of procedures December 2018 Helseatlas SKDE report Num. 3/2018 Authors Bård Uleberg, Sivert Mathisen, Janice Shu, Lise Balteskard, Arnfinn Hykkerud Steindal, Hanne Sigrun Byhring, Linda Leivseth and Olav Helge Førde Editor Barthold Vonen Awarding authority Ministry of Health and Care Services, and Northern Norway Regional Health Authority Date (Norwegian version) November 2018 Date (English version) December 2018 Translation Allegro (Anneli Olsbø) Version December 18, 2018 Front page photo: Colourbox ISBN: 978-82-93141-35-8 All rights SKDE. Foreword The publication of this updated day surgery atlas is an important event for several reasons. The term day surgery covers health services characterised by different issues and drivers. While ‘necessary care’ is characterised by consensus about indications and treatment and makes up about 15% of the health services, ‘preference-driven care’ is based more on the preferences of the treatment providers and/or patients. The preference-driven services account for about 25% of health services. The final and biggest group, which includes about 60% of all health services, is often called supply-driven and can be described as ‘supply creating its own demand’. Day surgery is a small part of the public health service in terms of resource use. However, it is a service that can be used to treat more and more conditions, and it is therefore becoming increasingly important for both clinical and resource reasons. How day surgery is prioritised and delivered is very important to patient treatment and to the legitimacy of the public health service. Information about how this health service is distributed in the population therefore serves as an important indicator of whether we are doing our job and whether the regional health authorities are fulfilling their responsibility to provide healthcare to their region’s population. -

The Economic Burden of Tnfα Inhibitors and Other Biologic Treatments in Norway

ClinicoEconomics and Outcomes Research Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH The economic burden of TNFα inhibitors and other biologic treatments in Norway Jan Norum1 Objective: Costly biologic therapies have improved function and quality of life for patients Wenche Koldingsnes2 suffering from rheumatic and inflammatory bowel diseases. In this survey, we aimed to document Torfinn Aanes3 and analyze the costs. Margaret Aarag Antonsen4 Methods: In 2008, the total costs of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors and other biologic Jon Florholmen5 agents in Norway were registered prospectively. In addition to costs, the pattern of use in the Masahide Kondo6 four Norwegian health regions was analyzed. The expenses were calculated in Norwegian krone and converted into Euros. 1Northern Norway Regional Results: The pattern of use was similar in all four regions, indicating that national guidelines Health Authority, Bodø, Norway; 2Department of Rheumatology, are followed. Whereas the cost was similar in the southeast, western, and central regions, the For personal use only. University Hospital of North Norway, expenses per thousand inhabitants were 1.56 times higher in the northern region. This indicates Tromsø, Norway; 3Drug Procurement that patients in the northern region experienced a lower threshold for access to these drugs. The Cooperation, Oslo, Norway; 4Hospital Pharmacy of North Norway Trust, gap in costs between trusts within northern Norway was about to be closed. The Departments Tromsø, Norway; 5Department of of Rheumatology and Gastroenterology had the highest consumption rates. Gastroenterology, University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø, Norway; Conclusion: The total cost of biologic agents was significant. -

The State's Ownership Report 2006

THE STATE’S OWNERSHIP REPORT 2006 The Norwegian State Ownership Report 2006 comprises 52 companies in which the Definitions ministries administer the State’s direct ownership interests. The companies presented in this report include both companies with commercial objectives and the largest, most The list below contains definitions of the concepts used in • Capital employed – Equity plus interest-bearing debt important companies with sectoral policy objectives. this report. Please note that these definitions may deviate from those used by the companies, as several of these • Dividend ratio – funds set aside for dividends as a concepts are defined differently by the companies. proportion of the annual profit for the group. The State Ownership Report CATEGORY 1 – Companies with CATEGORY 4 – Companies with 3 The State Ownership Report 2006 commercial objectives sectoral policy objectives • Rate of return – Here used on matters pertaining to • The geometric average has been used to calculate the The Minister 50 Argentum Fondsinvesteringer AS 78 Avinor AS shares. The rate of return consists of the change in average profit share. 4 The State – an active, long-term owner 51 Baneservice AS 79 Bjørnøen AS value of the share plus the dividends paid. The geome- The Year 2006 52 Eksportfinans ASA 80 Enova SF tric average is used to calculate the average annual rate • Equity ratio – Equity as a percentage of total capital. 6 The Year 2006 for the State as 53 Entra Eiendom AS 81 Gassco AS of return, and account has been taken of the increase in Shareholder 54 Flytoget AS 82 Industritjeneste AS the value of dividends paid by assuming that dividends • Total remuneration to the Chief Executive Officer Key Figures 55 Mesta AS 83 Kings Bay AS have been reinvested to give a rate of return correspon- – salaries, pensions and other forms of remuneration in 11 Rates of return and values 56 SAS AB 84 Kompetansesenter for IT ding to five-year state bonds. -

Gynaecology Healthcare Atlas 2015–2017 Helseatlas Hospital Referral Areas and Adjustment SKDE

Gynaecology Healthcare Atlas 2015–2017 Helseatlas Hospital referral areas and adjustment SKDE The following fact sheets use the terms ‘hospital referral area’ and ‘adjusted for age’. These terms are explai- ned below. Aver. Hospital referral areas Inhabitants age Akershus 67% 201,911 47.2 The regional health authorities have a responsibility to provide satis- Vestre Viken 64% 196,644 48.6 Bergen 67% 178,531 46.7 factory specialist health services to the population in their catchment Innlandet 59% 166,569 50.3 area. In practice, it is the individual health trusts and private provi- Stavanger 70% 140,197 45.6 St. Olavs 66% 127,895 46.9 ders under a contract with a regional health authority that provide and Sørlandet 64% 120,307 47.8 Østfold 62% 119,927 49.2 perform the health services. Each health trust has a hospital referral OUS 72% 109,435 45.0 area that includes specific municipalities and city districts. Different Møre og Romsdal 61% 104,957 49.0 Vestfold 61% 95,564 49.3 disciplines can have different hospital referral areas, and for some ser- UNN 63% 77,413 48.2 Telemark 60% 71,665 49.8 vices, functions are divided between different health trusts and/or pri- Fonna 63% 70,749 48.2 vate providers. The Gynaecology Healthcare Atlas uses the hospital Hospital referral area Lovisenberg 84% 62,639 38.6 Diakonhjemmet 67% 59,811 46.3 referral areas for specialist health services for medical emergency ca- Nordland 61% 56,144 49.0 Nord-Trøndelag 61% 55,459 49.3 re. -

Caesarean Section Rates and Activity-Based Funding in Northern Norway: a Model-Based Study Using the World Health Organization’S Recommendation

Hindawi Obstetrics and Gynecology International Volume 2018, Article ID 6764258, 6 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6764258 Research Article Caesarean Section Rates and Activity-Based Funding in Northern Norway: A Model-Based Study Using the World Health Organization’s Recommendation Jan Norum 1,2 and Tove Elisabeth Svee3 1Department of Surgery, Hammerfest Hospital, Hammerfest, Norway 2Department of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Science, UiT-#e Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø, Norway 3Department of Obstetrics, University Hospital of North Norway, Harstad, Norway Correspondence should be addressed to Jan Norum; [email protected] Received 23 December 2017; Revised 7 June 2018; Accepted 26 June 2018; Published 16 July 2018 Academic Editor: Mohamed Mabrouk Copyright © 2018 Jan Norum and Tove Elisabeth Svee. ,is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Objective. Caesarean section (CS) rates vary significantly worldwide. ,e World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended a maximum CS rate of 15%. Norwegian hospitals are paid per CS (activity-based funding), employing the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system. We aimed to document how financial incentives can be affected by reduced CS rates, according to the WHO’s recommendation. Methods. We employed a model-based analysis and included the 2016 data from the Norwegian Patient Registry (NPR) and the Medical Birth Registry of Norway (MBRN). ,e vaginal birth rate and CS rates of each hospital trust in Northern Norway were analyzed. Results. ,ere were 4,860 deliveries and a 17.5% CS rate (range 13.9–20.3%). -

Adverse Events in Deceased Hospitalised Cancer Patients As A

Haukland et al. BMC Palliative Care (2020) 19:76 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00579-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Adverse events in deceased hospitalised cancer patients as a measure of quality and safety in end-of-life cancer care Ellinor Christin Haukland1,2* , Christian von Plessen3,4,5, Carsten Nieder1,6 and Barthold Vonen2,7 Abstract Background: Anticancer treatment exposes patients to negative consequences such as increased toxicity and decreased quality of life, and there are clear guidelines recommending limiting use of aggressive anticancer treatments for patients near end of life. The aim of this study is to investigate the association between anticancer treatment given during the last 30 days of life and adverse events contributing to death and elucidate how adverse events can be used as a measure of quality and safety in end-of-life cancer care. Methods: Retrospective cohort study of 247 deceased hospitalised cancer patients at three hospitals in Norway in 2012 and 2013. The Global Trigger Tool method were used to identify adverse events. We used Poisson regression and binary logistic regression to compare adverse events and association with use of anticancer treatment given during the last 30 days of life. Results: 30% of deceased hospitalised cancer patients received some kind of anticancer treatment during the last 30 days of life,mainlysystemicanticancertreatment. These patients had 62% more adverse events compared to patients not being treated last 30 days, 39 vs. 24 adverse events per 1000 patient days (p < 0.001, OR 1.62 (1.23–2.15). They also had twice the odds of an adverse event contributing to death compared to patients without such treatment, 33 vs. -

Obstetrics Healthcare Atlas

Obstetrics Healthcare Atlas The use of obstetrics healthcare services in Norway during the period 2015–2017 April 2019 Helseatlas SKDE report Num. 6/2019 Authors Hanne Sigrun Byhring, Lise Balteskard, Janice Shu, Sivert Mathisen, Linda Leivseth, Arnfinn Hykkerud Steindal, Frank Olsen, Olav Helge Førde and Bård Uleberg Professional contributor Pål Øian Editor Barthold Vonen Awarding authority Ministry of Health and Care Services, and Northern Norway Regional Health Authority Date (Norwegian version) April 2019 Date (English version) August 2019 Translation Allegro (Anneli Olsbø) Version August 26, 2019 Front page photo: Colourbox ISBN: 978-82-93141-41-9 All rights SKDE. Foreword, Northern Norway RHA Norwegian antenatal and maternity care is of high international quality. Considerable efforts have gone into developing a comprehensive maternity care since the submission of Report No 12 to the Storting (2008–2009) - En gledelig begivenhet (‘A happy event’ - in Norwegian only) and the publication of the Norwegian Directorate of Health’s guide Et trygt fødetilbud (‘Safe maternity services’ - in Norwegian only). The guide and the subsequent regional discipline plans have provided a basis for developing even better described and more predictable maternity care. The quality requirements have been clarified and the requirements that apply to maternity units have been specified. Cooperation between specialist communities across institutional boundaries have helped to develop more uniform and medically documented practices. It is therefore pleasing, and perhaps also expected, that SKDE’s eighth healthcare atlas shows that overall, mothers and babies receive good and equitable health services throughout pregnancy and childbirth. This is primarily important to the women and the babies born, as it allows them to feel safe before the most important event in life. -

For Peer Review Only Journal: BMJ Open

BMJ Open BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010700 on 25 April 2016. Downloaded from Does the rate of adverse events identified by the Global Trigger Tool depend on the sample size? An observational study of retrospective record reviews of two different sample sizes For peer review only Journal: BMJ Open Manuscript ID bmjopen-2015-010700 Article Type: Research Date Submitted by the Author: 30-Nov-2015 Complete List of Authors: Mevik, Kjersti; Nordland Hospital Trust, Regional patient safety resource center Hansen, Tonje; Nordland Hospital Trust, Medical director Deilkås, Ellen; Akershus University Hospital, Centre for Health Service Research Griffin, Frances; Fran Griffin and Associates, LLC Vonen, Barthold; The Artic University of Norway, Institute for community medicine; Nordland Hospital Trust, CMO <b>Primary Subject Qualitative research Heading</b>: Secondary Subject Heading: Health services research http://bmjopen.bmj.com/ QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, Quality in health care < HEALTH SERVICES Keywords: ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT, Global Trigger Tool, Sample size, Adverse events < THERAPEUTICS on October 1, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. For peer review only - http://bmjopen.bmj.com/site/about/guidelines.xhtml Page 1 of 23 BMJ Open 1 BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010700 on 25 April 2016. Downloaded from 2 3 Does the rate of adverse events identified by the Global Trigger Tool depend on the sample 4 size? An observational study of retrospective record reviews of two different sample sizes 5 6 7 8 9