Meme-Work: Psychoanalysis and the Alt-Right Ivan Knapp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

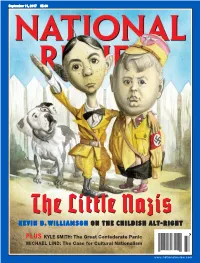

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

Unlikely Hegemons

sponding to this. Employment, as wage labour, ne- Stiegler’s critique of automation is inarguably cessarily implies proletarianisation and alienation, dialectical and, in its mobilisation of the pharmakon, whereas for Marx, ‘work can be fulflling only if it impeccably Derridean. Yet it leaves unanswered – ceases to be wage labour and becomes free.’ The de- for the moment at least, pending a second volume – fence of employment on the part of the left and la- the question of the means through which the trans- bour unions is then castigated as a regressive posi- ition from employment to work might be effected. tion that, while seeking to secure the ‘right to work’, This would surely require not only the powers of in- only shores up capitalism through its calls for the dividual thought, knowledge, refection and critique maintenance of wage labour. Contrariwise, automa- that Stiegler himself affrms and demonstrates in tion has the potential to fnally release the subject Automatic Society, but also their collective practice from the alienation of wage labour so as to engage and mobilisation. What is also passed over in Stie- in unalienated work, properly understood as the pur- gler’s longer term perspectives is the issue of how suit, practice and enjoyment of knowledge. What such collective practices, such as already exist, are currently stands in the way of the realisation of ful- to respond to the more immediate and contempor- flling work, aside from an outmoded defense of em- ary effects of automation, if not through the direct ployment, Stiegler notes, is the capture of the ‘free contestation of the conditions and terms of employ- time’ released from employment in consumption, ment and unemployment. -

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

![Arxiv:2001.07600V5 [Cs.CY] 8 Apr 2021 Leged Crisis (Lilly 2016)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6394/arxiv-2001-07600v5-cs-cy-8-apr-2021-leged-crisis-lilly-2016-86394.webp)

Arxiv:2001.07600V5 [Cs.CY] 8 Apr 2021 Leged Crisis (Lilly 2016)

The Evolution of the Manosphere Across the Web* Manoel Horta Ribeiro,♠;∗ Jeremy Blackburn,4 Barry Bradlyn,} Emiliano De Cristofaro,r Gianluca Stringhini,| Summer Long,} Stephanie Greenberg,} Savvas Zannettou~;∗ EPFL, Binghamton University, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign University♠ College4 London, Boston} University, Max Planck Institute for Informatics r Corresponding authors: manoel.hortaribeiro@epfl.ch,| ~ [email protected] ∗ Abstract However, Manosphere communities are scattered through the Web in a loosely connected network of subreddits, blogs, We present a large-scale characterization of the Manosphere, YouTube channels, and forums (Lewis 2019). Consequently, a conglomerate of Web-based misogynist movements focused we still lack a comprehensive understanding of the underly- on “men’s issues,” which has prospered online. Analyzing 28.8M posts from 6 forums and 51 subreddits, we paint a ing digital ecosystem, of the evolution of the different com- comprehensive picture of its evolution across the Web, show- munities, and of the interactions among them. ing the links between its different communities over the years. Present Work. In this paper, we present a multi-platform We find that milder and older communities, such as Pick longitudinal study of the Manosphere on the Web, aiming to Up Artists and Men’s Rights Activists, are giving way to address three main research questions: more extreme ones like Incels and Men Going Their Own Way, with a substantial migration of active users. Moreover, RQ1: How has the popularity/levels of activity of the dif- our analysis suggests that these newer communities are more ferent Manosphere communities evolved over time? toxic and misogynistic than the older ones. -

The Alt-Right Comes to Power by JA Smith

USApp – American Politics and Policy Blog: Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith Page 1 of 6 Long Read Book Review: Deplorable Me: The Alt- Right Comes to Power by J.A. Smith J.A Smith reflects on two recent books that help us to take stock of the election of President Donald Trump as part of the wider rise of the ‘alt-right’, questioning furthermore how the left today might contend with the emergence of those at one time termed ‘a basket of deplorables’. Deplorable Me: The Alt-Right Comes to Power Devil’s Bargain: Steve Bannon, Donald Trump and the Storming of the Presidency. Joshua Green. Penguin. 2017. Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right. Angela Nagle. Zero Books. 2017. Find these books: In September last year, Hillary Clinton identified within Donald Trump’s support base a ‘basket of deplorables’, a milieu comprising Trump’s newly appointed campaign executive, the far-right Breitbart News’s Steve Bannon, and the numerous more or less ‘alt right’ celebrity bloggers, men’s rights activists, white supremacists, video-gaming YouTubers and message board-based trolling networks that operated in Breitbart’s orbit. This was a political misstep on a par with putting one’s opponent’s name in a campaign slogan, since those less au fait with this subculture could hear only contempt towards anyone sympathetic to Trump; while those within it wore Clinton’s condemnation as a badge of honour. Bannon himself was insouciant: ‘we polled the race stuff and it doesn’t matter […] It doesn’t move anyone who isn’t already in her camp’. -

Pepe the Frog

PEPE THE FROG: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies by BEN PETTIS A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Spring 2018 An Abstract of the Thesis of Ben Pettis for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the School of Journalism and Communication to be taken Spring 2018 Title: Pepe the Frog: A Case Study of the Internet Meme and Its Potential Subversive Power to Challenge Cultural Hegemonies Approved: _______________________________________ Dr. Peter Alilunas This thesis examines Internet memes, a unique medium that has the capability to easily and seamlessly transfer ideologies between groups. It argues that these media can potentially enable subcultures to challenge, and possibly overthrow, hegemonic power structures that maintain the dominance of a mainstream culture. I trace the meme from its creation by Matt Furie in 2005 to its appearance in the 2016 US Presidential Election and examine how its meaning has changed throughout its history. I define the difference between a meme instance and the meme as a whole, and conclude that the meaning of the overall meme is formed by the sum of its numerous meme instances. This structure is unique to the medium of Internet memes and is what enables subcultures to use them to easily transfer ideologies in order to challenge the hegemony of dominant cultures. Dick Hebdige provides a model by which a dominant culture can reclaim the images and symbols used by a subculture through the process of commodification. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives $6.95

CANADIAN CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES MAY/JUNE 2018 $6.95 Contributors Ricardo Acuña is Director of Alex Himelfarb is a former Randy Robinson is a the Parkland Institute and federal government freelance researcher, sits on the CCPA’s Member’s executive with the Privy educator and political Council. Council, Treasury Board, and commentator based in Vol. 25, No. 1 numerous other departments, Toronto. Alyssa O’Dell is Media and ISSN 1198-497X and currently chairs or serves Public Relations Officer at the Luke Savage writes and Canada Post Publication 40009942 on various voluntary boards. CCPA. blogs about politics, labour, He chairs the advisory board The Monitor is published six times philosophy and political a year by the Canadian Centre for Marc Edge is a professor of of the CCPA-Ontario. culture. Policy Alternatives. media and communication Elaine Hughes is an at University Canada West Edgardo Sepulveda is an The opinions expressed in the environmental activist in in Vancouver. His last book, independent consulting Monitor are those of the authors several non-profit groups and do not necessarily reflect The News We Deserve: The economist with more than including the Council of the views of the CCPA. Transformation of Canada’s two decades of utility Canadians, where she chairs Media Landscape, was (telecommunications) policy Please send feedback to the Quill Plains (Wynyard), published by New Star Books and regulatory experience. [email protected]. Saskatchewan chapter. in 2016. He writes about electricity, Editor: Stuart Trew Syed Hussan is Co-ordinator inequality and other Senior Designer: Tim Scarth Matt Elliott is a city columnist of the Migrant Workers economic policy issues at Layout: Susan Purtell and blogger with Metro Editorial Board: Peter Bleyer, Alliance for Change. -

S.C.R.A.M. Gazette

MARCH EDITION Chief of Police Dennis J. Mc Enerney 2017—Volume 4, Issue 3 S.c.r.a.m. gazette FBI, Sheriff's Office warn of scam artists who take aim at lonely hearts DOWNTOWN — The FBI is warning of and report that they have sent thousands of "romance scams" that can cost victims dollars to someone they met online,” Croon thousands of dollars for Valentine's Day said. “And [they] have never even met that weekend. person, thinking they were in a relationship with that person.” A romance scam typically starts on a dating or social media website, said FBI spokesman If you meet someone online and it seems "too Garrett Croon. A victim will talk to someone good to be true" and every effort you make to online for weeks or months and develop a meet that person fails, "watch out," Croon relationship with them, and the other per- Croon said. warned. Scammers might send photos from son sometimes even sends gifts like flowers. magazines and claim the photo is of them, say Victims can be bilked for hundreds or thou- they're in love with the victim or claim to be The victim and the other person are never sands of dollars this way, and Croon said the unable to meet because they're a U.S. citizen able to meet, with the scammer saying they most common victims are women who are 40 who is traveling or working out of the coun- live or work out of the country or canceling -60 years old who might be widowed, di- try, Croon said. -

108 Left History 6.1 Edward Alexander, Irving Howe

108 Left History 6.1 Edward Alexander, Irving Howe -Socialist, Critic,Jew (Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1998). "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds ..." -Emerson It is interesting to speculate on how Irving Howe, student of Emerson, would have responded to this non-biographic, not-quite-intellectual-historical survey of his career. For it is a study that keeps demanding an impossible consistency from a life ever responding to changing intellectual currents. And the responses come from first a very young, then a middle-aged, and eventually an older, concededly wiser writer. Alexander's title promises four themes, but develops only three. We have socialist, critic, Jew; we don't have the man, Irving Howe. In place of a thesis, Alexander offers strong opinions: praise of Howe for letting the critic in him eventually moderate the socialism and the secular Jewishness, but scorn for his remaining a socialist and for never becoming, albeit Jewish, a practicing Jew. If Howe could have responded at all, it would, of course, have been in a dissent. Yet he might have smiled at Alexander's attempts to come to tenns with one infuriating consistency: Howe's passion for whatever he thought and whatever he did, even when he was veering 180 degrees from a previous passion. Mostly, the book is a seriatim treatment of Howe's writings, from his fiery youthful Trotskyite pieces to his late conservative attacks on joyless literary theorists. Alexander summarizes each essay or book in order of appearance, compares its stance to that of its predecessors or successors, and judges them against an implicit set of unchanging values of his own, roughly identifiable to a reader as the later political and religious positions of Commentary magazine. -

What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels?

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters Peace Studies 5-15-2019 What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels? Olivia Young Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/peace_studies_student_work Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Young, Olivia, "What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels?" (2019). Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters. 1. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/peace_studies_student_work/1 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Peace Studies at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peace Studies Capstone Thesis What role has social media played in violence perpetrated by Incels? Olivia Young May 15, 2019 Young, 1 INTRODUCTION This paper aims to answer the question, what role has social media played in violence perpetrated by Incels? Incels, or involuntary celibates, are members of a misogynistic online subculture that define themselves as unable to find sexual partners. Incels feel hatred for women and sexually active males stemming from their belief that women are required to give sex to them, and that they have been denied this right by women who choose alpha males over them. -

The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams by Cynthia A. Burkhead A

Dancing Dwarfs and Talking Fish: The Narrative Functions of Television Dreams By Cynthia A. Burkhead A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Ph.D. Department of English Middle Tennessee State University December, 2010 UMI Number: 3459290 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3459290 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DANCING DWARFS AND TALKING FISH: THE NARRATIVE FUNCTIONS OF TELEVISION DREAMS CYNTHIA BURKHEAD Approved: jr^QL^^lAo Qjrg/XA ^ Dr. David Lavery, Committee Chair c^&^^Ce~y Dr. Linda Badley, Reader A>& l-Lr 7i Dr./ Jill Hague, Rea J <7VM Dr. Tom Strawman, Chair, English Department Dr. Michael D. Allen, Dean, College of Graduate Studies DEDICATION First and foremost, I dedicate this work to my husband, John Burkhead, who lovingly carved for me the space and time that made this dissertation possible and then protected that space and time as fiercely as if it were his own. I dedicate this project also to my children, Joshua Scanlan, Daniel Scanlan, Stephen Burkhead, and Juliette Van Hoff, my son-in-law and daughter-in-law, and my grandchildren, Johnathan Burkhead and Olivia Van Hoff, who have all been so impressively patient during this process.