Securities Litigation & Regulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re Payment Card Interchange Fee Litigation

In re Payment Card Interchange Fee and Merchant..., Not Reported in... 2006 WL 6846702 lawsuits against the defendant credit card networks and certain of their member banks alleging that the defendants 2006 WL 6846702 have fixed transaction costs known as “interchange fees” Only the Westlaw citation is currently available. at supra-competitive levels in violation of Section One of United States District Court, E.D. New York. the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1. See Carney Dec. Ex. 1 (Complaint in Photos Etc. Corp., et al., v. Visa U.S.A. Inc., In re PAYMENT CARD INTERCHANGE et al., CV 05–1007 (D. Conn. June 22, 2005) (the “Photos FEE AND MERCHANT DISCOUNT Complaint”)). Many of those actions were brought on ANTITRUST LITIGATION. behalf of a putative class, while several others were This document refers to: All Actions. brought by individual merchants acting alone. By order of the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation dated MDL No. 05–1720(JG)(JO). October 19, 2005, fourteen such lawsuits that had been | commenced in four separate districts were consolidated Aug. 7, 2006. in the current litigation for pretrial purposes. DE 2. Since then, more thirty-six additional cases have been transferred to this MDL action. See DE 57; DE 94; DE SEALED MEMORANDUM AND ORDER 144; DE 314. The following factual background, drawn from the Photos complaint, explains the transaction fees JAMES ORENSTEIN, United States Magistrate Judge. at issue and the plaintiffs' allegations. 2 *1 By notice dated December 21, 2005, defendants MasterCard Incorporated and MasterCard International Defendants MasterCard and Visa are payment card Incorporated (collectively “MasterCard”) moved to networks that are owned, respectively, by their thousands disqualify attorney K. -

Annual Report 2007

The Thomson Corporation Annual Report 2007 2 To Our Shareholders 64 Financial Statements and Notes 6 I am 110 Board of Directors 18 Thomson 2007 Financial Highlights 112 Senior Management 24 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 113 Corporate Information We are like you. At Thomson, our success depends on being trusted, on staying ahead, on having the answers others need in order to succeed. We are certain we have what it takes, because we have put the right model at the center of our design. You, the professional. The Thomson Corporation is a leading provider of critical information, decision support tools and related services to professionals in the legal, financial, tax and accounting, scientific and healthcare sectors. Thomson integrates its unique proprietary databases with third party data, software and analytical tools to create essential workflow solutions for business and professional clients around the world. We provide information platforms and services to support faster, better decisions that are more informed, more considered and more immediate. We have fashioned our solutions to provide the most relevant and trusted data instantly – intelligent information that helps you put your knowledge to work. This book is a tribute to you and our thanks for the trust you place in us. 1 To Our Shareholders: 2007 was a milestone year for The Thomson Corporation. The company’s name was in the headlines more often than perhaps at any other time in its history. On a Friday in May we announced our agreement to sell Thomson Learning, and on the following Tuesday we announced an agreement to buy Reuters Group PLC for nearly $18 billion.* The sale of our Thomson Learning assets for more than $8 billion was a resounding success. -

RBC Capital Markets Telecommunications, Media

THOMSON REUTERS Susan Taylor Martin President, Legal Special Note Safe Harbor / Forward-Looking Statements •This presentation consists of these slides and the associated remarks and comments, which are related and intended to be presented and understood together. •This presentation contains forward-looking statements, including, without limitation, those related to the outlook, prospects and operating performance of our Legal business segment. Forward-looking statements are those which are not historical facts. These and other statements that relate to future results and events are based on Thomson Reuters current expectations. •Our actual results in future periods may differ materially from those currently expected because of a number of risks and uncertainties. The risks and uncertainties that we believe are material are outlined in our disclosure filings and materials, which you can find on www.thomsonreuters.com. Please consult these documents for a more complete understanding of these risks and uncertainties. We disclaim any intention or obligation to update or revise any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, except as may be required by law. Forward-looking statements are provided for the purpose of providing information about current expectations. This information may not be appropriate for other purposes. 2 Legal’s Evolution Traditional Thomson Reuters Mindset Jurisdiction Specific Law Firm Centric Content-First Entry What’s Changed Power to Buyside Technology Development -

Refinitiv UK Parent Limited

DocuSign Envelope ID: 03AE1696-6072-4AFF-8189-06C441DF1ED5 Registration number: 11273092 Refinitiv UK Parent Limited Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 December 2019 DocuSign Envelope ID: 03AE1696-6072-4AFF-8189-06C441DF1ED5 Refinitiv UK Parent Limited Contents Strategic Report 1 to 3 Directors' Report 4 to 7 Independent Auditor's Report 8 to 13 Profit and Loss Account 14 Statement of Financial Position 15 Statement of Changes in Equity 16 Notes to the Financial Statements 17 to 39 DocuSign Envelope ID: 03AE1696-6072-4AFF-8189-06C441DF1ED5 Refinitiv UK Parent Limited Strategic Report for the Year Ended 31 December 2019 The directors present their strategic report and the audited financial statement for the financial year ended 31 December 2019. Definitions As used in this annual report, the "Group" and "Refinitiv" refers to the Refinitiv Holdings Limited and its subsidiary undertakings, including joint ventures and associates. The "Company" refers to Refinitiv UK Parent Limited. Fair review of the business The principal activity of the Company is to act as a holding company and as a group treasury company. The Company was incorporated on 23 March 2018 and comparative numbers for the previous year have been presented accordingly. The loss for the financial period amounted to $161,960,000 (2018: $32,410,000). As at 31 December 2019, the Company has a net asset position of $2,589,659,000 (2018: $2,701,767,000). Principal risks and uncertainties As a holding company, the principal risks and uncertainties are limited to its investment portfolio. The Company may be required to take future impairment charges that would reduce the reported assets and earnings as a result of realising the underlying assets. -

Sweet & Maxwell

SWEET & MAXWELL PROFESSIONAL CATALOGUE 2014 SWEET & MAXWELL REUTERS/Neil Hall REUTERS/Neil LEGAL SOLUTIONS FROM THOMSON REUTERS We deliver best-of-class legal solutions to help you practise LEGAL RESEARCH, NEWS AND BUSINESS INFORMATION the law, manage your organisation and help you and your Westlaw UK | Westlaw International business grow. LEGAL UPDATES & CURRENCY Lawtel Our solutions include Sweet & Maxwell commentary, Practical Law, Westlaw UK, Lawtel, and a series of software solutions LEGAL KNOW-HOW Practical Law including Serengeti, Solcara and Thomson Reuters Elite. FEDERATED SEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT Intelligently connect your work and your world with our Solcara content, expertise and technologies. TRAINING AND EDUCATION Legal Conferences and Webinars See a better way forward at thomsonreuters.com/ukirelandlegal IN-HOUSE LEGAL DEPARTMENT MANAGEMENT Serengeti LAW FIRM MANAGEMENT Thomson Reuters Elite LAW BOOKS Sweet & Maxwell BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT & MARKETING FindLaw WELCOME TO THE SWEET & MAXWELL 2014 PROFESSIONAL CATALOGUE Great content, delivered flexibly. It’s at the heart of what we do at Thomson Reuters. Our Sweet & Maxwell commentary titles, used by thousands of legal professionals every day, bring clarity to complex matters and give you the confidence to make the big decisions. This year’s catalogue is packed with the most authoritative legal voices, tackling the issues of today. Among the hundreds of specialist titles, you can look forward to new editions of: The White Book Archbold: Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice Sealy & Milman: Annotated Guide to the Insolvency Legislation The Mental Health Act Manual Clerk & Lindsell on Torts McGregor on Damages Benjamin’s Sale of Goods Hudson’s Building and Engineering Contracts View our complete catalogue at sweetandmaxwell.co.uk With our professional-grade eBook app, Thomson Reuters Proview™, you can experience these trusted practitioner texts in entirely new ways on the iPad, Mac, PC and in beta on Android tablets. -

Informe De Situación Economía, Industria Y Mercado De La

Economía, industria y mercado de la información en 2013 – Tomàs Baiget e Isabel Olea E. MERCADO, INDUSTRIA Y SECTOR INFORMACIÓN Informe de situación Economía, industria y mercado de la información en 2013 Tomàs Baiget e Isabel Olea Baiget, Tomàs; Olea, Isabel (2014). “Economía, industria y mercado de la información en 2013”. Anuario ThinkEPI, 2014, v. 8, pp. 243-255. Resumen: Características y datos económicos de algunos productos y aspectos concretos del mercado de la informa- ción. Los datos provienen de varias fuentes y por ello re- sultan algo heterogéneos. Se ofrecen valores del mercado mundial de la información, adquisiones de empresas, prin- cipales editoriales científicas, mercados editoriales (países), coste de las bases de datos WoK y Scopus, revalorización de la información económica a partir de la crisis de 2008, incre- mento del precio de las revistas, coste de la informática (Ley de Moore) y principales vendedores. Palabras clave: Mercado, Precios, Costes, Editoriales, In- dustria de la información, Adquisiciones de empresas, WoK, Scopus, Información económica, Precio de las suscripciones, Revistas, Principales editoriales científicas, Acceso abierto, Informática. Title: The information economy, industry and market in 2013 Abstract: Characteristics and economic data of the information market come from various sources and are somewhat mixed. Specific aspects and products discussed are the valuation of the global information market, corporate acquisitions, major scientific publishers, publishing markets (countries), cost of WoK and Scopus databases, revaluation of economic information since the 2008 crisis, journal price increases, open access market, evolution of computing costs (Moore’s Law) and major vendors. Keywords: Markets, Prices, Costs, Publishers, Information industry, Company acquisitions, WoK, Scopus, Economic information, Subscription prices, Journals, Major scientific publishers, Open access, OA, STM publishers. -

At Mrs. Murphy's Bed and Breakfast

FORMAN DAVID 8/28/2012 For Educational Use Only A ROOM FOR “ADAM AND STEVE” AT MRS. MURPHY'S..., 23 Colum. J. Gender... Columbia Journal of Gender and Law David M. Forman 1 Copyright © 2012 by the Columbia Journal of Gender and Law; David M. Forman Abstract This article aims to encourage a vital and evolutionary step forward in understanding how multifaceted legal processes shape, and should shape, thinking about gay and lesbian couples within religious communities and the body politic. The article begins by providing context that illustrates the place-based and diffuse nature of an ongoing culture war between civil rights and religious freedom, further exposing the painful irony inherent in using misinterpretations of the Sodom and Gomorrah parable to reinforce inhospitality. The article describes a state-by-state patchwork of nondiscrimination laws governing places of public accommodation and explores the Jim Crow origins of the “Mrs. Murphy” exception that has been incorporated into a handful of state nondiscrimination laws. The article then examines how existing legal frameworks address claims of sexual orientation discrimination alongside defenses based upon religious freedom. Finally, this article seeks to accelerate an emerging trend toward including sexual orientation as a protected category in our nation's nondiscrimination laws, by highlighting an opportunity to counter religious misinterpretations currently reflected in the prevailing cultural narrative. *327 I. Re-Introducing “Adam and Steve” Since at least the 1970s, the phrase “Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve” has been used by conservative Christians (and others) to express opposition to civil rights claims by gays and lesbians. -

Instructions for Refinitiv Bill to Legal Entity Changes

The Financial and Risk business of Thomson Reuters is now Refinitiv refinitiv.com Instructions for Refinitiv Bill to Legal Entity Changes The Refinitiv Bill to Legal Entity file details up-to-date information relating to supplier invoice submission , such as Legal Entity name, Bill To/Registered Address, tax registration numbers, mailing addresses(where invoices are submitted in hard copy ) and e-mail ids for electronic submission of invoices. The file also highlights any legal entity names, calling out both the old and the new legal entity names along with the date on which the name change becomes effective. Note: This is a dynamic document with updates made on a weekly basis, where required, till all changes have been finalized. Please therefore continue to refer to this portal to confirm and check invoice submission protocols Guidelines to be followed while referring to the Document: 1. The file provides country-wise-legal entity names- old names(where the invoices used to be addressed) to Vs new legal entity name(where the invoices should be billed to going forward) 2. Bill to Registered address- The address which needs to be printed on the invoice along with the Legal Entity name 3. Tax Registration number- This is mandatory information to be printed on the invoices for all VAT applicable countries. 4. Invoice mailing address- This is the physical mailing address and should be used only where hard copy requirement is mandatory for invoice submission. The vendors are requested not to send physical invoices where Soft Copy requirements apply- Refer column Hard copy/Soft Copy for more details. -

Norton Bankruptcy Law Adviser 2002 No. 2 Fulton Excerpt

Reprinted from Norton Bankruptcy Law Adviser, 2021 No. 2 (February 2021), with permission of Thomson Reuters. Copyright © 2021. Further use without the permission of Thomson Reuters is prohibited. For further information about this publication, please visit https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/products/law-books or call 800.328.9352. NORTON BANKRUPTCY LAW ADVISER Monthly Analysis of Important Issues and Recent Developments in Bankruptcy Law Managing Editor: Hon. Keith M. Lundin, United States Bankruptcy Judge (1982-2016), Nashville, TN Board of Contributing Editors: Hon. John T. Gregg, United States Bankruptcy Judge, Western District of Michigan; Scott B. Cohen, Engelman Berger, PC, Phoenix, Arizona; Andrew J. Currie, Venable LLP, Washington, D.C.; Eugene J. Geekie Jr., Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr LLP, Chicago, Illinois; Paul R. Hage, Jaffe Raitt Heuer & Weiss, Southfield, Michigan Editor-in-Chief: William L. Norton III, Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP, Nashville, Tennessee February 2021 Issue 2 CITY OF CHICAGO v. FULTON—A IN THIS ISSUE: City of Chicago v. Fulton—A REJECTION OF THE MAJORITY RULE Rejection of the Majority Rule 1 By Kenneth N. Klee and Sasha M. Gurvitz By Kenneth N. Klee and Sasha M. * Gurvitz 1 In a decision authored by Justice Alito, the Supreme Court holds Recent Decisions From The in City of Chicago v. Fulton that a non-debtor’s mere retention of Appellate Courts 6 Erin Malone-Smolla property of the estate after the filing of a bankruptcy petition does Bethany Davenport not constitute an act to exercise control over property -

2019 Fact Book Is Intended to Provide a Broad-Based Information Set to Investors and to Serve As a Detailed Reference Guide for Our Shareholders

Fact Book 2019 The intelligence, technology, and human expertise you need to find trusted answers. Table of Contents 3 The 2019 Fact Book is intended to provide a broad-based information set to investors and to serve as a detailed reference guide for our shareholders. This Fact Book provides an introduction to the "new" Thomson Reuters, from our overarching strategy to specific featured solutions. It also provides summary and detailed information regarding the company’s operating segments and financial metrics. We discuss our results from continuing operations on both an IFRS and non-IFRS basis. On October 1, 2018, we sold 55% of our former Financial & Risk (F&R) business. We reported F&R as a discontinued operation through October 1, 2018, and, except for diluted earnings (loss) per share and cash flow, exclude the results of our former F&R business. Our IFRS results include our “Share of post-tax (losses) earnings in equity method investments”, beginning from the fourth quarter of 2018. Adjusted earnings, a non-IFRS measure, excludes our share of post-tax results in equity method investments. Business Historical Financial Business 4 Overview 16 Information 28 Segments 6 Business Overview 18 Historical Financial 30 Legal Professionals Information 7 Revenues by Segment 38 Corporates 9 Business Model and Key 19 Key Metrics 46 Tax Professionals Operating Characteristics 20 Segment Information 54 Reuters 10 Opportunity 22 Share Price Performance 56 Global Print 12 Our Strategy 23 Returns to Shareholders 15 Executive Team 24 Common Share Dividend -

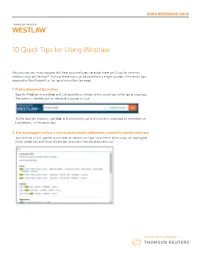

10 Quick Tips for Using Westlaw

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE 10 Quick Tips for Using Westlaw Westlaw contains many features that help you do effi cient research. Here are 10 tips for common research tasks on Westlaw®. Many of these tasks can be done from a single location – the search box, powered by WestSearch®, at the top of every Westlaw page. 1. Find a document by citation Type the Find command ( fi nd: or fi : ), followed by a citation, in the search box at the top of any page. The format is fl exible and not sensitive to spaces or case. To fi nd multiple citations, type fi nd: or fi : followed by up to 30 citations, separated by semicolons or hard returns, in the search box. 2. Use autosuggest to fi nd a case by party name, publication, content to search and more To search for a case, specifi c publication or content set, type a few letters of what you are looking for in the search box and select the content you want from the drop-down list. QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE 3. Check a citation in KeyCite to determine whether your case, statute, administrative decision, or regulation is still good law Type the KeyCite® command ( keycite: or kc: ), followed by a citation, in the search box. Note: For a reminder of what the fl ags mean, click the Powered by KeyCite at the top of a document 4. Run searches in plain language or Terms and Connectors Use plain language or Terms and Connectors to search on Westlaw. WestSearch, a search engine designed specifi cally for law, incorporates over 125 years of proprietary analysis of the law and exclusive tools like Key Numbers, KeyCite, headnotes, notes of decisions, indexes, and secondary sources to deliver relevant results no matter what type of search you run. -

Legal Offshoring: a Welcome Change to the American Legal Profession

LEGAL OFFSHORING: A WELCOME CHANGE TO THE AMERICAN LEGAL PROFESSION R. Alexander Johnson This essay is submitted to satisfy the expository writing requirement at the University of Tennessee College of Law and is solely the work of the undersigned. ______________________________ R. Alexander Johnson Submitted May 30th, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction……………………………………………………………………………1 I. The Current State of Legal Offshoring…………………………………………… 3 A. Offshoring Companies…………………………………………………….. 5 B. Law Firms Offshoring………………………………………………………9 C. In-house Corporate Counsel Offshoring………………………………….12 II. Benefits of Legal Offshoring………………………………………………………15 III. Ethical Implications of Offshoring………………………………………………19 A. Conflicts of Interest………………………………………………………..22 B. Confidentiality of Client Information…………………………………….24 C. Disclosure to Client………………………………………………………...26 D. Fee Arrangements………………………………………………………….28 E. Ethical Offshoring Solutions………………………………………………31 IV. Anti-Offshoring Legislation………………………………………………………32 A. Various Forms of Anti-Offshoring Legislation………………………….. 34 B. Constitutional Considerations……………………………………………...35 C. Foreign Governments’ Reactions to Offshoring………………………….36 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………38 Appendix A……………………………………………………………………………...40 Appendix B……………………………………………………………………………...43 Appendix C……………………………………………………………………………...49 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………….50 INTRODUCTION This past May, law schools across America held commencement ceremonies and conferred approximately 44,000 law degrees.1 While