Mike Leigh -Auteur? in the Social and Cultural Foundations of Language, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Image Spam Detection: Problem and Existing Solution

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 06 Issue: 02 | Feb 2019 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Image Spam Detection: Problem and Existing Solution Anis Ismail1, Shadi Khawandi2, Firas Abdallah3 1,2,3Faculty of Technology, Lebanese University, Lebanon ----------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Today very important means of communication messaging spam, Internet forum spam, junk fax is the e-mail that allows people all over the world to transmissions, and file sharing network spam [1]. People communicate, share data, and perform business. Yet there is who create electronic spam are called spammers [2]. nothing worse than an inbox full of spam; i.e., information The generally accepted version for source of spam is that it crafted to be delivered to a large number of recipients against their wishes. In this paper, we present a numerous anti-spam comes from the Monty Python song, "Spam spam spam spam, methods and solutions that have been proposed and deployed, spam spam spam spam, lovely spam, wonderful spam…" Like but they are not effective because most mail servers rely on the song, spam is an endless repetition of worthless text. blacklists and rules engine leaving a big part on the user to Another thought maintains that it comes from the computer identify the spam, while others rely on filters that might carry group lab at the University of Southern California who gave high false positive rate. it the name because it has many of the same characteristics as the lunchmeat Spam that is nobody wants it or ever asks Key Words: E-mail, Spam, anti-spam, mail server, filter. -

The Imagined Voice 2017 JULY

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/58691 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Kyriakides, Y. Title: Imagined Voices : a poetics of Music-Text-Film Issue Date: 2017-12-21 Imagined Voices A Poetics of Music-Text-Film Yannis Kyriakides Imagined Voices A Poetics of Music-Text-Film Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden op gezag van Rector Magnificus prof.mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op donderdag 21 december 2017 klokke 15.00 uur door Yannis Kyriakides geboren te Limassol (CY) in 1969 Promotores Prof. Frans de Ruiter Universiteit Leiden Prof.dr. Marko Ciciliani Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, Graz Copromotor Dr. Catherine Laws University of York/ Orpheus Instituut, Gent Promotiecommissie Prof.dr. Marcel Cobussen Universiteit Leiden Prof.dr. Nicolas Collins School of the Art Institute of Chicago Prof.dr. Sander van Maas Universiteit van Amsterdam Prof.dr. Cathy van Eck Bern University of the Arts Dr. Vincent Meelberg Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen/ docARTES, Gent Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen Academy of Creative and Performing Arts (ACPA) Table of Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 4 PART I: Three Voices 16 Chapter 1: The Mimetic Voice 17 1.1 Art Imitates 18 1.2 Cognitive Immersion 24 1.3 Vocal Embodiment 27 1.4 Subvocalisation 32 1.5 Inner Speech 35 1.6 Silent Voices 38 Chapter 2: The Diegetic Voice 41 2.1 Narration 43 2.2 Paratext 46 2.3 Narrational Network 48 2.4 Temporality -

Hyper-Image Network?

HYPER-IMAGE NETWORK? An investigation into the role of text and image in the design of hypertext networks with specific consideration of the World Wide Web By Axel Vogelsang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design University of the Arts, London March 2008 1 For Hecki 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS HYPER-IMAGE NETWORK? ........................................................................................... 1 Table of Contents .............................................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................... 6 Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 8 List of Illustrations ........................................................................................................... 9 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 23 1.1 Preface ................................................................................................................. 23 1.2 Terminology ......................................................................................................... 31 1.3 Chapter Overview ............................................................................................... 34 1.4 Literature review -

Anti-Spam Methods

INTRODUCTION Spamming is flooding the Internet with many copies of the same message, in an attempt to force the message on people who would not otherwise choose to receive it. Most spam is commercial advertising, often for dubious products, get-rich-quick schemes, or quasi- legal services. Spam costs the sender very little to send -- most of the costs are paid for by the recipient or the carriers rather than by the sender. There are two main types of spam, and they have different effects on Internet users. Cancellable Usenet spam is a single message sent to 20 or more Usenet newsgroups. (Through long experience, Usenet users have found that any message posted to so many newsgroups is often not relevant to most or all of them.) Usenet spam is aimed at "lurkers", people who read newsgroups but rarely or never post and give their address away. Usenet spam robs users of the utility of the newsgroups by overwhelming them with a barrage of advertising or other irrelevant posts. Furthermore, Usenet spam subverts the ability of system administrators and owners to manage the topics they accept on their systems. Email spam targets individual users with direct mail messages. Email spam lists are often created by scanning Usenet postings, stealing Internet mailing lists, or searching the Web for addresses. Email spams typically cost users money out-of-pocket to receive. Many people - anyone with measured phone service - read or receive their mail while the meter is running, so to speak. Spam costs them additional money. On top of that, it costs money for ISPs and online services to transmit spam, and these costs are transmitted directly to subscribers. -

French Digital Literatures Between Work and Text Susan Joan Cronin

Digital Text and Physical Experience: French Digital Literatures Between Work and Text Susan Joan Cronin King’s College, Cambridge September 2018 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy Abstract Digital Text and Physical Experience: French Digital Literatures Between Work and Text Susan Joan Cronin This thesis takes into consideration the presence of computers and electronic equipment in French literary and multimedia discussions, beginning in the first chapter with the foundation of the Oulipo group in 1960 and taking as a starting point the group's conceptions of the computer in relation to literature. It proceeds in the second chapter to explore the materialities and physical factors that have informed the evolution of ideas related to the composition and reading of digital texts, so as to illuminate some of the differences that may be purported to exist between e-literatures and traditional print works. Drawing on Roland Barthes' 'Between Work and Text,' the chapters gradually progress into an exploration of spatiality in digital and interactive literatures, taking into account the role of exhibitions in accommodating and diffusing these forms in France, notably the 1985 exhibition 'Les Immatériaux,' to whose writing installations the third chapter is dedicated. The first three chapters thus focus on computer assisted reading and writing prior to 1985. The chapters that form the second half of the thesis deal with more recent years, exploring online and mobile application works, reading these as engendering their own distinct physical spaces that extend beyond the 'site' of the work - both the website or display and the tactile materials on which the work is operated - creating in relation to the reading what Roberto Simanowski terms a 'semiotic body'. -

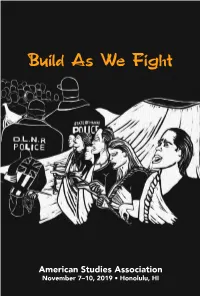

Build As We Fight

Build As We Fight American Studies Association November 7–10, 2019 • Honolulu, HI AMERICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION PRESIDENTS, 1951 TO PRESENT Carl Bode, 1951–1952 Paul Lauter, 1994–1995 Charles Barker, 1953 Elaine Tyler May, 1995–1996 Robert E. Spiller, 1954–1955 Patricia Nelson Limerick, 1996–1997 George Rogers Taylor, 1956–1957 Mary Helen Washington, 1997–1998 Willard Thorp, 1958–1959 Janice Radway, 1998–1999 Ray Allen Billington, 1960–1961 Mary C. Kelley, 1999–2000 William Charvat, 1962 Michael Frisch, 2000–2001 Ralph Henry Gabriel, 1963–1964 George Sánchez, 2001–2002 Russel Blaine Nye, 1965–1966 Stephen H. Sumida, 2002–2003 John Hope Franklin, 1967 Amy Kaplan, 2003–2004 Norman Holmes Pearson, 1968 Shelley Fisher Fishkin, 2004–2005 Daniel J. Boorstin, 1969 Karen Halttunen, 2005–2006 Robert H. Walker, 1970–1971 Emory Elliott, 2006–2007 Daniel Aaron, 1972–1973 Vicki L. Ruiz, 2007–2008 William H. Goetzmann, 1974–1975 Philip J. Deloria, 2008–2009 Leo Marx, 1976–1977 Kevin K. Gaines, 2009–2010 Wilcomb E. Washburn, 1978–1979 Ruth Wilson Gilmore, 2010–2011 Robert F. Berkhofer Jr., 1980–1981 Priscilla Wald, 2011–2012 Sacvan Bercovitch, 1982–1983 Matthew Frye Jacobson, 2012–2013 Michael Cowan, 1984–1985 Curtis Marez, 2013–2014 Lois W. Banner, 1986–1987 Lisa Duggan, 2014–2015 Linda K. Kerber, 1988–1989 David Roediger, 2015–2016 Allen F. Davis, 1989–1990 Robert Warrior, 2016–2017 Martha Banta, 1990–1991 Kandice Chuh, 2017–2018 Alice Kessler-Harris, 1991–1992 Roderick Ferguson, 2018–2019 Cecelia Tichi, 1992–1993 Scott Kurashige, 2019–2020 Cathy N. Davidson, 1993–1994 Dylan Rodriguez, 2020–2021 COVER Our cover was designed bu Joy Lehuanani Enomoto, a mixed media visual artist and social justice activist. -

A Primer of Found Poetry

A Primer of Found Poetry John Bevis www.johnbevis.com Attribution Good artists borrow. Great artists steal. - Pablo Picasso A bad writer borrows, a good writer steals outright! - Mark Twain It reminds me of a well-known quote by Handel – "Good composers borrow, great composers steal." As Oscar Wilde said – or was it TS Eliot? – anyway, he said “Good poets borrow; great poets steal." "Good artists borrow; great artists steal," said Picasso or TS Eliot or Salvador Dali – no one seems to know which. I think it was Keith Richards who said good artists borrow, great ones steal. -found poem composed from results from an internet search INDEX What is found poetry 4 Types of found poem 1: Intact text 7 The prime poem Accidentals Translations The retrieved poem Types of found poem 2: Selected text 14 Notes on the selection of text Single poetic source Multiple poetic source Single non-poetic source Multiple non-poetic source Types of found poem 3: Adapted text 22 Hybrid Found format Analytic Synthetic Systemic Text and visuals The Making of a Found Poem 29 The finding and the source Methods and the effects of poeticisation Change of context, change of meaning Provenance The origins of Found Poetry 32 Some Found Poets and their practice 35 Epilogue 45 WHAT IS FOUND POETRY? Back in 2007, I gave a reading that included some found poems. It seemed a good idea to say something about them, and about found poetry in general. Not having a neat definition of found poetry of my own, I went online to see what other people had to say. -

Digital Technology and Innovative Poetry Tom Jenks

Digital Technology and Innovative Poetry Tom Jenks Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Edge Hill University, December 2017. Acknowledgements For Sarah, Alex and Mina. With thanks to the following for support, encouragement and conversation: Joanne Ashcroft, Lucy Harvest Clarke, Wayne Clements, Ailsa Cox, Sarah Crewe, James Davies, Lyndon Davies, Nikolai Duffy, Stephen Emmerson, Patricia Farrell, Steven Fowler, Peter Jaeger, Chris McCabe, Alec Newman, Ian Seed, Chris Stephenson, Philip Terry, Scott Thurston, Gareth Twose, Catherine Vidler, Nathan Walker, Joe Walton, Samantha Walton and the Poetry and Poetics Research Group at Edge Hill University. With particular thanks to Robert Sheppard and James Byrne. Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Appropriation ...................................................................................................................... 12 An Anatomy of Melancholy .............................................................................................................. 13 Appropriative, allegorical and conceptual writing ............................................................................ 23 Contextualisation and summary ...................................................................................................... -

IP Poetry Gustavo Romano

IP Poetry Gustavo Romano PLP 06 Post-Local Project MEIAC PLP 06 MEIAC IP PoetryGustavo Romano / MEIAC, Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo PLP06_110308:PLP 11/3/08 12:29 Página 1 IP Poetry Gustavo Romano PLP 06 Post-Local Project MEIAC, Museo Extremeño e Iberoamericano de Arte Contemporáneo PLP06_110308:PLP 11/3/08 12:29 Página 2 PLP06_110308:PLP 11/3/08 12:29 Página 3 Introducción 5 Descripción técnica 7 Memoria de eventos y exposiciones IP Poetry 13 Acerca del proyecto IP Poetry De poemas no humanos y cabezas parlantes 25 Belén Gache Poemas IP 65 Evolución de los IP Bots a través de los diferentes modelos 91 Currículum 101 English Texts 103 PLP06_110308:PLP 11/3/08 12:29 Página 4 PLP06_110308:PLP 11/3/08 12:29 Página 5 Introducción El proyecto IP Poetry consiste en el desarrollo de un sistema de software y hardware que utiliza material textual de Internet para la generación de poesía que luego será recitada en tiempo real por autómatas conectados a la red. Las diferentes instrucciones de búsqueda (por ejemplo, todas las frases que comiencen con las palabras “sueño que soy”) y el modo y la secuencia en la que serán recitadas (un robot por vez alternado resultados de búsquedas, recitando a dúo, etc.), conformarán la estructura y el sentido de cada poema IP. La forma de exhibición es performática y se da mediante la intervención de diferentes espacios públicos. Utilizando un sensor de proximidad, el sistema detecta la presencia del público y envía la orden a los robots para que comiencen a recitar los poemas creados especialmente para cada evento. -

Program Book (PDF Download)

Build As We Fight American Studies Association November 7–10, 2019 • Honolulu, HI AMERICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION PRESIDENTS, 1951 TO PRESENT Carl Bode, 1951–1952 Paul Lauter, 1994–1995 Charles Barker, 1953 Elaine Tyler May, 1995–1996 Robert E. Spiller, 1954–1955 Patricia Nelson Limerick, 1996–1997 George Rogers Taylor, 1956–1957 Mary Helen Washington, 1997–1998 Willard Thorp, 1958–1959 Janice Radway, 1998–1999 Ray Allen Billington, 1960–1961 Mary C. Kelley, 1999–2000 William Charvat, 1962 Michael Frisch, 2000–2001 Ralph Henry Gabriel, 1963–1964 George Sánchez, 2001–2002 Russel Blaine Nye, 1965–1966 Stephen H. Sumida, 2002–2003 John Hope Franklin, 1967 Amy Kaplan, 2003–2004 Norman Holmes Pearson, 1968 Shelley Fisher Fishkin, 2004–2005 Daniel J. Boorstin, 1969 Karen Halttunen, 2005–2006 Robert H. Walker, 1970–1971 Emory Elliott, 2006–2007 Daniel Aaron, 1972–1973 Vicki L. Ruiz, 2007–2008 William H. Goetzmann, 1974–1975 Philip J. Deloria, 2008–2009 Leo Marx, 1976–1977 Kevin K. Gaines, 2009–2010 Wilcomb E. Washburn, 1978–1979 Ruth Wilson Gilmore, 2010–2011 Robert F. Berkhofer Jr., 1980–1981 Priscilla Wald, 2011–2012 Sacvan Bercovitch, 1982–1983 Matthew Frye Jacobson, 2012–2013 Michael Cowan, 1984–1985 Curtis Marez, 2013–2014 Lois W. Banner, 1986–1987 Lisa Duggan, 2014–2015 Linda K. Kerber, 1988–1989 David Roediger, 2015–2016 Allen F. Davis, 1989–1990 Robert Warrior, 2016–2017 Martha Banta, 1990–1991 Kandice Chuh, 2017–2018 Alice Kessler-Harris, 1991–1992 Roderick Ferguson, 2018–2019 Cecelia Tichi, 1992–1993 Scott Kurashige, 2019–2020 Cathy N. Davidson, 1993–1994 Dylan Rodriguez, 2020–2021 COVER Our cover was designed bu Joy Lehuanani Enomoto, a mixed media visual artist and social justice activist. -

Guise and Excess in the Poetry of Barry Macsweeney

`I am Pearl': Guise and Excessin the Poetry of Barry MacSweeney Paul Batchelor NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ---------------------------- 207 32642 2 ---------------------------- PhD in English Literature Newcastle University September 2008 Abstract Barry MacSweeney was a prolific poet who embraced many poetic styles and forms. The defining characteristics of his work are its excess (for example, its depiction of extreme emotional states,its use of challenging forms, and the flagrancy with which it appropriates other writers and poems) and its quality of swerving (for example, the way it frustrates the reader's expectations, and its oppositional identification with literary antecedents and schools). I argue that MacSweeney's poetic development constitutes a series of reactions to a moment of trauma that occurred in 1968, when a crisis in his personal life coincided with a disastrous publicity stunt for his first book. I chart MacSweeney's progress from 1968 to 1997 in terms of five stages of trauma adjustment, which account for the stylistic changes his poetry underwent. In Chapter One I consider the ways in which the traumatic episode in 1968 led to MacSweeney embracing the underground poetry scene. In Chapter Two I examine the ways in which his 1970s poetry exhibits denial. In Chapter Three I look at Jury Vet and the other angry, alienated poetry he wrote in the early 1980s. In Chapter Four I look at 1984s Ranter, an example of poetic bargaining in which MacSweeney alludes to mainstream poetry in return for what he hopes will be a wider readership. In Chapter Five I consider Hellhound Memos, the collection that resulted from a period of depression MacSweeney suffered 1985- 1993.